Abenomics after 2 1/2 years

[First a few notes. An increasing number of comments are getting diverted to spam, where I have to fish them out. But I won’t know this unless you tell me. Try leaving a short comment alerting me if your longer one didn’t take. No, I didn’t kill your comment because you disagree with me—never have. Also, I have a new post at Econlog discussing DeLong and Krugman on Friedman, and yesterday one on Andrew Sentance.]

When Abe took office I expected his policies to raise inflation and NGDP, but not as much as he hoped. I expected his policies to help the labor market, but cautioned that a fairly low unemployment rate and rapidly falling labor force would limit the gains in RGDP. I think I got all the big issues right, but missed on some of the components of RGDP.

Inflation figures have recently been whipsawed by both a big sales tax boost and then falling oil prices. Assuming oil prices don’t fall much further, then when the dust settles next year I expect inflation to be about 1%. But Abenomics has clearly raised the trend rate of inflation (which was negative under his predecessors.)

NGDP growth has not been all that impressive, until you compare it to NGDP over the previous 2 decades:

1994:1 495 trillion

2012:4 472 trillion -4.6%

2015:2 500 trillion +5.9%

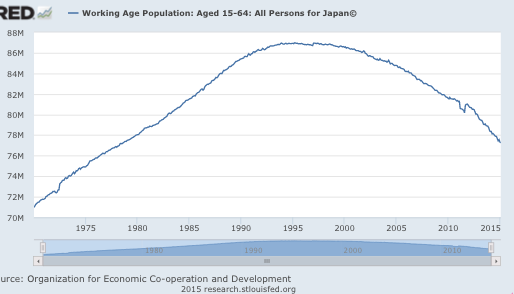

Without the sales tax increase last year, I’d guess NGDP would have been up about 4.0% to 5.0%. That’s a pretty slow rate of growth, less than 2%/year, but quite a turnaround from the previous 2 decades. Even more impressive, Abe took office just as the boomers were hitting retirement age. As a result the working age population is now falling much faster than during 1994-2012:

The working age population is now plunging at 1.4% per year. That fact alone makes the Japanese trend rate of RGDP growth about 2% lower than in the US, and the US trend rate is itself below 2%. (The Fed recently reduced their trend rate estimate to 2%; they’ll have to reduce it further in the future. BTW, with all of their talent it should not be possible for me to forecast which way they will miss, but I can do so, as can many others.)

The working age population is now plunging at 1.4% per year. That fact alone makes the Japanese trend rate of RGDP growth about 2% lower than in the US, and the US trend rate is itself below 2%. (The Fed recently reduced their trend rate estimate to 2%; they’ll have to reduce it further in the future. BTW, with all of their talent it should not be possible for me to forecast which way they will miss, but I can do so, as can many others.)

Any success I had predicting Japanese RGDP growth was dumb luck, as it reflected two offsetting factors that I missed:

1. Productivity has been horrible, worse than I expected

2. The labor force has been flat, despite the 1.4% annual decline in working age population. That’s better than I expected.

I suppose that second fact is mostly due to older Japanese working longer. Abe has also been trying to boost immigration, and female labor force participation. Perhaps that’s also played a role. (Immigrants are currently 1.1% of the workforce.)

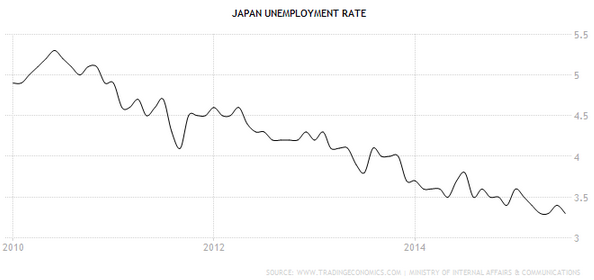

The unemployment rate has fallen to 3.3%, the lowest rate in 18 years.

Many Keynesians thought the big sales tax increase last year would be a mistake, but unemployment continued to decline and total employment rose. Another “austerity” prediction gone wrong. (Is anyone still keeping track of these failures? I’ve lost count.) The so-called “recession” of 2014 consisted of Japanese shoppers splurging in March to beat the April 1 tax increase, and then cutting back after the tax increase. Some Keynesians actually claimed that that showed fiscal policy matters.

Back when Japan had a higher unemployment rate, I emphasized that monetary stimulus could boost growth. Now with low unemployment and a falling population, I think the strongest argument for faster NGDP growth is their huge public debt.

If the number of 15-64 year olds had remained constant since 1991, Japan’s GDP would now be more than 8% higher (see figure 8).

Demographic decline was not, however, anything like the biggest drag on nominal GDP. That honor belongs to Japan’s stubborn deflation. If prices had remained flat since 1991, Japan’s nominal GDP would now be 20% higher. If prices had instead risen by 2% a year, consistent with international norms of price stability, nominal GDP would be over 80% bigger.

An 80% bigger NGDP would have meant a big fall in the public debt/GDP ratio, even accounting for the fact that nominal interest rates (and hence budget deficits) might have been a bit higher. Also recall, however, that faster NGDP growth would have meant at least slightly stronger RGDP growth, and also fewer wasteful Japanese fiscal projects such as bridges to nowhere. Both of those factors would have reduced the deficit.

Why have Abe’s policies been viewed as a mixed bag? Partly because the third arrow of supply side reforms haven’t had much effect, and hence real wages are still very weak. And while the sales tax increase is fiscally responsible, and necessary (since they can’t seem to cut spending), it’s obviously also painful.

Tags:

21. September 2015 at 08:33

> An 80% bigger NGDP would have meant a big fall in the public debt/GDP ratio, even accounting for the fact that nominal interest rates (and hence budget deficits) might have been a bit higher.

Could I ask for a bit more detail in the accounting here?

Had inflation been a constant and expected 2% per year with the real interest rate following the previous trend, I would expect Japan’s debt level to be more or less the same as now, save for depreciation of the existing stock of debt.

The price level change itself would not affect the relative level of debt, since all other things being equal government deficits — constant in real terms — would be nominally proportional to the price level.

How much of Japan’s public debt has been taken on since 1991, and what was the duration of Japan’s debt stock in 1991?

21. September 2015 at 08:45

Majromax, If I understand your argument correctly you are claiming that a 3% higher NGDP growth rate would have led to 3% higher nominal interest rates, and hence no change in the debt ratio (except for the reduction in the small pre-1991 legacy debt.)

Yes, that’s true if nominal rates rose by 3%, and there are no other offsetting factors. But I have a very different view:

1. The argument doesn’t apply at the zero bound. The US has had higher NGDP growth than Japan, but has also been at the zero bound since 2008. Japan’s NGDP growth has recently increased, but there has been absolutely no effect on nominal rates. I do agree that 2 decades of 3% faster NGDP growth would have meant somewhat higher nominal rates, but nowhere near 3% higher.

2. And that also fails to account for the fact that real government spending would have been lower if NGDP growth had been higher. More tax revenue would have been collected (even in real terms), and fewer bridges to nowhere, as there would be less need to boost AD.

21. September 2015 at 09:15

Scott, you say that productivity has been deceptive, but that workin age pop. Has been better than you expect. Perhaps one is the reverse of the others? (If WAP had fall 1,4% as you expected, productivity would have rise that, more or less).

I mean that Japan is trapped in an horrible trap, and only with very more immigration monetary policy can be effective. The one solution without migrants is an hard increasing productivity and that seems impossible.

21. September 2015 at 10:42

Hard to find fault with this Sumner post, since Sumner pleads ‘mea culpa’ for his mistakes. My two cents: I read this cheap book on Kindle and it’s quite good: “The ABE of Economics” by Edward Hugh; Sumner repeats some of the arguments found therein. But as for blasting Keynes followers for getting predictions wrong, here’s one by Keynes that’s right on point (except Keynes got the ‘very short’ part wrong, see below, as he failed to see the post-WWII Baby Boom):

“Perhaps the most outstanding example of a case where we have a considerable power of seeing into the future is the prospective trend of population. We know much more securely than we know almost any other social or economic factor relating to the future that, in the place of steady and indeed steeply rising level of population we have experienced for a great number of decades, we shall be faced in a very short time with a stationary or declining level. The rate of decline is doubtful but it is virtually certain that the changeover, compared to what we have been used to, will be substantial. We have this unusual degree of knowledge concerning the future because of the long but definite time-lag in the effects of vital statistics. Nevertheless the idea of the future being different from the present is so repugnant to our conventional modes of thought and behavior that we, most of us, offer a great resistance to acting on it in practice”.

Hugh, Edward (2014-06-18). The A B E of Economics: An Essay In Economic Folly

21. September 2015 at 10:58

Miguel, You said:

“I mean that Japan is trapped in an horrible trap, and only with very more immigration monetary policy can be effective.”

That’s a strange comment to make, given that the last 2 1/2 years disproves the idea that Japanese monetary policy is not effective. The yen has gone from 80 to the dollar to 120 to the dollar.

21. September 2015 at 11:23

A bit skeptical of the Japan “working age population” explanation. Doesn’t China have the same problem?

When I was a kid, Japan went from a country poorer than almost every U.S. state to a country wealthier than the median state by 1991. Since 1991, they’ve fallen back to the level of a poorer U.S. state.

As you know my pet theory is that the anti-growth effects we generally expect at negative 5% inflation can also manifest less strongly at inflation levels below 2-3%, in some situations.

21. September 2015 at 13:20

Whoa! I didn’t realize the U.S. working-age population suffered a massive slowdown beginning December 2007!

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/LFWA64TTUSM647S

Cool point about Japan’s working-age population, BTW. Italy’s GDP per capita was still falling as of the end of 2014. I don’t know what’s up with Italy. Its economy (especially productivity) is abysmal, much worse than that of Japan, but its population has stronger positive momentum than that of Japan.

Productivity’s been bad everywhere in the First World recently, but it is in the PIGS where it has been most abysmal.

Yes, China’s working-age population is also beginning to shrink in absolute terms, but its catch-up is not over. That’s why it’s economy is growing 5-7% per year. I expect China’s per capita income (PPP) to finish convergence with the West at Russia’s level.

21. September 2015 at 14:11

Interestingly, the expansion from 2002 to 2007 and from 2009 to 2014 look remarkably similar: unemployment fell from 5.4% to 3.7% in the first case, 5.2% to 3.4% in the second (using December data for each year). Employment rose from 63.12 million to 64.50 million in the first case and from 62.90 million to 63.76 million in the second. Nominal GDP grew 0.5%/yr in the first case and 0.7%/yr in the second. Stock prices (Nikkei) grew 12.3%/yr from 12/31/02 to 12/31/07 and 10.6%/yr from 12/31/09 to 12/31/14.

Looking at Japanese unemployment over the past 6 years, it doesn’t seem like anything interesting at all has happened there. Unemployment declined on a consistent if noisy trend throughout the whole period.

21. September 2015 at 14:31

Am I the only one who finds conventional rhetoric on Japan at this stage quite puzzling? Unemployment has fallen to its lowest level since the late 90s, and if the (fairly consistent) downward trend continues, in 3 years we’ll be looking at levels in the 2-2.5% range, comparable to the Japanese economy before the Lost Decade. By that point, presumably tight labor markets will be pushing up the rate of wage growth and bringing Japan closer to its inflation target.

One might say that there’s no reason to expect unemployment (and its crucial determinant, aggregate demand) to continue displaying this kind of momentum. In the abstract, that’s certainly true – but in the specific Japanese case there’s an obvious reason for continued progress, namely the very weak yen. The BIS puts Japan’s broad trade-weighted real exchange rate index at around 70, compared to around 100 in 2012 immediately prior to Abenomics. See http://www.bis.org/statistics/eer.htm

It’s true that there hasn’t been as much improvement in the trade balance, so far, as many people had expected. But this is hardly evidence (as many observers seem to be taking it) that Japan’s export and import elasticities are near zero! There are almost always lags in the trade response to exchange rates; and crucially there was an earlier, substantial rise in the yen (with the BIS index going from the 80-90 range to over 100) associated with the Great Recession and its aftermath. In the initial stages of Abenomics and yen depreciation, trade flows may have been influenced by the lagged effects of this rise. And the full decline in the yen index didn’t happen until recently, in response to the global rise of the dollar in late 2014.

There simply hasn’t been enough time to conclude that Japan’s weak yen policy will somehow fail to translate into substantially increased net exports (and thereby stronger aggregate demand). And I’m frankly a little baffled to hear this hypothesis so casually tossed around – when it would require that for Japan, even the most pessimistic estimates of trade elasticities are not pessimistic enough. Yes, there isn’t any kind of consensus in the literature: “macro” estimates, inferred from aggregate data, tend to be much lower than “micro” estimates, built from facts about the underlying markets. But even the macro estimates – at least the ones I’ve seen – in developed countries are generally in the range 0.5-2, both for export supply and import demand. If you take ‘1’ to be the elasticity in both cases, then for a country like Japan (where imports and exports are running around 16% of GDP right now), an exogenous 30% decline in the exchange rate would lead to a gain in net exports worth over 10% of GDP. That’s absolutely massive, more than enough to achieve full employment and any desired level of inflation. And this isn’t pie-in-the-sky speculation: it’s just taking elasticities from the relatively “pessimistic” branch of the literature at face value.

The one somewhat valid response to this, I think, is to say that Japan has seen a secular decline in its equilibrium real exchange rate. Indeed, the BIS data starts at the beginning of 1994 with Japan at an RER index of around 130, skyrocketing to a peak of 150 in 1995 and then settling down to 100-120 in the second half of the 90s – all well above its level throughout the 2000s. No doubt Japan’s strength in some key tradable industries has indeed weakened over time, and to some extent the yen decline may be needed merely to offset that external weakness (you know, “never reason from a price change”). But no matter how you look at it, I think, the yen is remarkably weak right now, and it’s hard to see why the giant depreciation we’ve just seen won’t ultimately have an effect. See, for instance, this OECD graph of the real exchange rate adjusting for manufacturing industry unit labor cost: https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/CCRETT02JPQ661N

So, as this rant illustrates, I remain deeply puzzled by all the rhetoric about Japan’s weak macroeconomic prospects. As Scott mentions, maybe some of the pessimism comes from the poor productivity and real wage growth, which are certainly abysmal. But a lot of the discussion seriously seems to view Japan’s reflationary monetary program as having failed, when from my perch it seems to be (1) humming along decently even now and (2) poised for substantial further gains.

(It’ll be interesting to come back to this comment in a few years and see how it fares. Markets have the 10-year inflation breakeven for Japan at 1%, which is actually not bad at all – it’s roughly the *same* as France, and it compares to only 1.5% in the US. I wonder if even this is too pessimistic, but it does reveal that the market still thinks Abenomics has been a partial success – and that in this respect it’s at odds with much of the media. Reminiscent of the media’s view in late 1987 that bringing down the superdollar after the Plaza Accord had been a failure – right before net exports improved substantially over the next several years: https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=1TSy )

21. September 2015 at 14:44

Also, side note – for the 80s episode in the US, there is an amusing 1987 BPEA article from Paul Krugman and Richard Baldwin looking in real time at exactly this puzzle: why had the trade deficit stayed so large even a couple years after the fall of the dollar? http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/1987-1/1987a_bpea_krugman_baldwin_bosworth_hooper.PDF

Their hypothesis was that this was the combination of (1) lags in adjustment and (2) some secular decline in the value of the dollar associated with any given trade balance. The lags at issue in (1) weren’t just lags in response to the decline, but lags in response to the earlier rise: as of 1985 when the decline began, there had been a sudden upward movement to the exchange rate for several years, and trade flows were still very much in the process of adjusting to that.

Overall, the 1987 Krugman view holds up remarkably well. The lag view (1) is vindicated by the fact that shortly after publication, net exports took off, while some version of the secular decline view (2) is supported by any casual eyeballing of the long-term trajectory of the dollar and trade deficit. If history repeats itself, we may be seeing additional gains in Japan’s net exports quite soon…

21. September 2015 at 15:31

E. Harding,

I wonder to what extent changes in the level of immigration can explain that demographic shift.

Also, what was it about 1974, 1984, and 1987 that got couples so excited?

21. September 2015 at 15:33

In general, I agree with this post but with the caveat that the average resident of Japan has $6,000 yen equivalent in paper cash. Not in the bank—in the house.

The economic recovery may be better than we know in Japan, or it could be worse than we know. The so called mom-and-pop stores in Japan do not take plastic, so it would be interesting to know if they are flourishing.

As for Japan’s public debt to GDP ratio, my understanding is that within a few years the Bank of Japan will have liquidated a major portion of their public debt. And they still don’t have a problem with inflation.

This last topic deserves a post—possibly instructive for the US and heresy besides!

21. September 2015 at 17:17

TallDave, Those facts are wrong. Japan was never even close to being as rich as the US. They’ve fallen back since 1991, but only slightly, maybe from 75% as rich to 70% as rich.

Also wrong about China, their working age pop. is falling, but very slowly (not at all like Japan.)

E. Harding, China will surpass Russia, IMHO.

Matt, Good comment. I suppose competition from China has hurt some key sectors of the Japanese economy. Maybe that reduced the equilibrium real exchange rate.

21. September 2015 at 18:21

Demographic decline was not, however, anything like the biggest drag on nominal GDP. That honor belongs to Japan’s stubborn deflation.

What is the demograpic decline is the main cause the the stubborn deflation?

21. September 2015 at 18:25

@ I was thinking of writing a post on why it won’t (substantially), but I can only finish it on Friday, if that. Maybe I could work on it on Tuesday.

@W. Peden

-Yeah, those were upward revisions due to underestimated immigration. 🙂

21. September 2015 at 20:23

Sumner: “That’s a strange comment to make, given that the last 2 1/2 years disproves the idea that Japanese monetary policy is not effective. The yen has gone from 80 to the dollar to 120 to the dollar.” – according to money neutrality, this should not matter. Exports will increase but people will buy less imports, so as a whole it’s a wash. One of the problems with Japan is that, until recently, the people saved too much money, and Japan had to look outside its own country for demand, via exports. This is true for most of Asia.

22. September 2015 at 02:23

E. Harding,

That makes more sense. I thought it might have been amnesties, but then I looked up some US history and it wasn’t.

22. September 2015 at 05:29

OT- Scott, you might find this interesting:

http://slatestarcodex.com/2015/09/22/beware-systemic-change/#comments

22. September 2015 at 05:40

Matt

Very good comment. I’ve been wondering the same thing myself.

In addition to lags and changes in RER, I think maybe you need to consider a) in-elasticity of demand by product and by market and b) oligopoly supply in certain export sectors which results in increased margins instead of increased supply.

IMHO the efficacy of Japanese monetary policy is highly dependent on fx effects. Normally, you would see increases in domestic investment and consumption as a result of OMP, but when expected after tax returns in Japan are very low or negative (due to systemic problems like high taxes and excessive regulation), then instead you see purchases of foreign assets with a resulting drop in the fx rate.

Another interesting question is the extent to which inflation has been driven solely by changes in the fx rate and higher import costs. I think the other factor was political pressure on large firms to accept higher wage increases in the annual spring wage negotiations. I certainly don’t think domestic demand has had much impact on inflation.

22. September 2015 at 05:59

@Matt – ” If you take ‘1’ to be the elasticity in both cases, then for a country like Japan (where imports and exports are running around 16% of GDP right now), an exogenous 30% decline in the exchange rate would lead to a gain in net exports worth over 10% of GDP. That’s absolutely massive, more than enough to achieve full employment and any desired level of inflation.”

But in fact there has been a 30% decline in the exchange rate, from 80 to 120, as Sumner points out, and none of what you claim happened. Time to rethink your thesis.

22. September 2015 at 09:27

Krugman: Rate rage in 1932 http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/09/22/rate-rage-in-1932/?_r=0

22. September 2015 at 10:33

Scott — World Bank disagrees with you. In 1991, the US average is at 24,405 while Japan is at 20,466, or about $4K. Today the gap is 54,629.5 to 36,426, or about $18K — 4 to 5 times larger in real terms. (Note that the median U.S. state is poorer than the US average, which is why Japan could be richer than the median state in 1991.)

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?page=4

And again, look at Japan’s growth in the two decades before 1991. The shift was too radical to be explained by demographics, just as Chinese demographics have nothing to do with the growth story there.

22. September 2015 at 10:39

Or to use your preferred measure, Japan fell from 84% of US income to 67%, a fall of 17% or about three times your estimate of 5%.

Remember too, in 1991 it was widely expected the Japanese would be wealthier than the United States by 2001, based the the prior growth trend.

22. September 2015 at 11:05

Scott, what I mean is that deacresing population can only be compensated by increasing productivity. The MP in the last two and a half years has could be quite effective because there were a lot of underutilized resources. But I think that in absence of a constant improvement in MFP, the effectiveness of MP will decay. W’ll see.

22. September 2015 at 16:55

@Scott Sumner

-TallDave is right. The drop has been at least 15 points:

https://againstjebelallawz.wordpress.com/2015/08/22/the-great-axis-stagnation/

22. September 2015 at 17:01

Brian, Thanks, he’s always interesting.

Talldave, You said:

“World Bank disagrees with you.”

That’s funny, I could have sworn it disagrees with you. Seriously, if you used GDP per working age adult you’d probably get closer to what I claimed–which was just a guess. I’m actually a Japan pessimist, who argues they’ve tended to fall behind the US in recent decades. Others (like Krugman?) suggest that per capita GDP in Japan is doing as well as in the US.

You said:

“in 1991 it was widely expected the Japanese would be wealthier than the United States by 2001”

Not by me. Perhaps by Lester Thurow, who was wrong about just about everything.

Miguel, It’s not clear whether you are talking about real or nominal GDP. Monetary policy affects nominal GDP in the long run.

22. September 2015 at 17:03

dtoh, You said:

“I certainly don’t think domestic demand has had much impact on inflation.”

Given the turnaround in NGDP growth, surely it’s had some effect.

23. September 2015 at 05:00

Scott — GDP per working age adult is a problematic way to measure income given that the oldest quintile is also the wealthiest — they may not work much but they do invest.

At any rate, even within the OECD income differences dwarf demographic differences, to say nothing of across all nations.

Something changed in Japan in 1991.

23. September 2015 at 06:14

Talldave, Yes, we all know that Japanese growth slowed after 1991, as did growth in almost all developed economies, except perhaps the US.

A don’t understand your point about elderly people saving and GDP.

23. September 2015 at 09:58

In the long run? that is great! So, producrivity and so on, all depends on MP?

23. September 2015 at 15:07

You hace discovered the only real important in economy. NGDP. All the rest is not at all relevant. Great I’d name it Disneyland economy.

23. September 2015 at 17:05

@scott

I said, “I certainly don’t think domestic demand has had much impact on inflation.”

You said, “Given the turnaround in NGDP growth, surely it’s had some effect.”

Pretty minimal pretty sure it all is driven by supply side costs, but we shall see.

24. September 2015 at 12:45

Miguel, You seem to be confusing NGDP with productivity.

dtoh, If it was supply side inflation then RGDP growth would have slowed. You need to look at the NGDP data, which tells us demand has been the main factor.

26. September 2015 at 04:11

[…] goodness is economics a difficult subject. (Scott Sumner is implicitly surprised too.) So why is this […]

26. September 2015 at 04:48

[…] goodness is economics a difficult subject. (Scott Sumner is implicitly surprised too.) So why is this […]

29. September 2015 at 13:24

“Many Keynesians thought the big sales tax increase last year would be a mistake, but unemployment continued to decline and total employment rose. Another “austerity” prediction gone wrong.”

Not according to Masazumi Wakatabe

Professor of Economics, Faculty of Political

Science and Economics

Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan?

” . . . but the original version of Abenomics consisted of expansionary fiscal policy, not fiscal consolidation. Indeed, it should be noted that the transformation of Abenomics from expansion to austerity in the form of the consumption tax increase in April 2014 is the main reason why Abenomics is faltering and has not yet defeated deflation.”

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/19a53d1e-65e4-11e5-a57f-21b88f7d973f.html#axzz3nAFOHD3r