Reply to George Selgin

George Selgin has a very thoughtful post that starts off as follows:

Although my work on the “Productivity Norm” has led to my being occasionally referred to as an early proponent of Market Monetarism, mine has not been among the voices calling out for more aggressive monetary expansion on the part of the Fed or ECB as a means for boosting employment.*

I’m very happy that there are dissenting voices like George Selgin, as I’d hate for market monetarism to become a cult. In my view the most distinguished proponent of NGDP targeting is Bennett McCallum, and I seem to recall that he is also skeptical of the need for monetary stimulus at this time. (He favors growth rate targeting.) If Hayek were alive, he’d probably be skeptical. I also seem to recall that Larry White is skeptical. (Someone correct me if I’m wrong on any of these.) So there’s plenty of intellectual firepower arguing that NGDP targeting doesn’t imply the need for more stimulus.

George continues:

There are several reasons for my reticence. The first, more philosophical reason is that I think the Fed is quite large enough–too large, in fact, by about $2.8 trillion, about half of which has been added to its balance sheet since the 2008 crisis. The bigger the Fed gets, the dimmer the prospects for either getting rid of it or limiting its potential for doing mischief. A keel makes a lousy rudder.

I have a counter-intuitive take on this issue. I believe additional stimulus would actually reduce the Fed’s footprint on the economy. In Australia, where trend NGDP growth is about 7%, the base is only 4% of GDP. In the US where NGDP growth has averaged about 2% since mid-2008, the base is about 18% of NGDP. In Japan where NGDP growth is negative, the base is about 23% of GDP. Of course Japan has slightly lower bond yields that the US, which has much lower bond yields that Australia. It’s a demand for money story. Now I don’t favor 7% NGDP growth, I think that’s too high, but if we had averaged 3% or 4% NGDP growth since mid-2008, I believe that the Fed’s footprint right now might well be a bit smaller than 18% of GDP. And the economy would be doing better.

The second reason is that I worry about policy analyses (such as this recent one) that treat the “gap” between the present NGDP growth path and the pre-crisis one as evidence of inadequate NGDP growth. I am, after all, enough of a Hayekian to think that the crisis of 2008 was itself at least partly due to excessively rapid NGDP growth between 2001 and then, which resulted from the Fed’s decision to hold the federal funds rate below what appears (in retrospect at least) to have been it’s “natural” level.

I basically agree with George on this point. I’ve never followed Krugman’s practice of looking at how we are doing in comparison to the peak of the previous business cycle, which was late 2007. In most cases a cyclical peak is above the economy’s natural rate of output, i.e. the economy is somewhat overheated. Here’s where things get tricky. In principle, the Fed should have an explicit trend line, and then we wouldn’t have to guess where we are. We could then ignore RGDP, the unemployment rate, and any other real variable—just focus on NGDP. But since they don’t have an explicit NGDP target path, both George and I are forced to make an independent judgement about what sort of starting point seems reasonable. I’ve always used mid-2008, for several reasons. NGDP and RGDP growth had been slow for 6 months, suggesting we were no longer at the peak. Unemployment had risen from about 4.5% to 5.6%, which the Fed considers to be roughly the natural rate of unemployment. I certainly don’t think it’s possible to know the exact natural rate of unemployment, and I’d rather not look at it at all for policy purposes. But when starting out one needs to make some sort of assumption about whether we are near equilibrium, or whether employment needs to adjust. A 5% NGDP growth target from late 2007 would have been too high in my view, and 5% path from mid-2009 would have been too low. But I acknowledge that’s a judgment call.

My third reason for hesitating to endorse proposals for doing more than merely sustaining the present 4-5 percent NGDP growth rate is the one I consider most important. It is also one that has been gaining strength since 2009, to the point of now inclining me, not only to keep my own council when it comes to arguments for and against calls for more aggressive monetary expansion, but to join those opposing any such move.

My third reason stems from pondering the sort of nominal rigidities that would have to be at play to keep an economy in a state of persistent monetary shortage, with consequent unemployment, for several years following a temporary collapse of the level of NGDP, and despite the return of the NGDP growth rate to something like its long-run trend.

Apart from some die-hard New Classical economists, and the odd Rothbardian, everyone appreciates the difficulty of achieving such downward absolute cuts in nominal wage rates as may be called for to restore employment following an absolute decline in NGDP. Most of us (myself included) will also readily agree that, if equilibrium money wage rates have been increasing at an annual rate of, say, 4 percent (as was approximately true of U.S. average earnings around 2006), then an unexpected decline in that growth rate to another still positive rate can also lead to unemployment. But you don’t have to be a die-hard New Classicist or Rothbardian to also suppose that, so long as equilibrium money wage rates are rising, as they presumably are whenever there is a robust rate of NGDP growth, wage demands should eventually “catch down” to reality, with employees reducing their wage demands, and employers offering smaller raises, until full employment is reestablished. The difficulty of achieving a reduction in the rate of wage increases ought, in short, to be considerably less than that of achieving absolute cuts.

U.S. NGDP was restored to its pre-crisis level over two years ago. Since then both its actual and its forecast growth rate have been hovering relatively steadily around 5 percent, or about two percentage points below the pre-crisis rate.The growth rate of U.S. average hourly (money) earnings has, on the other hand, declined persistently and substantially from its boom-era peak of around 4 percent, to a rate of just 1.5 percent.** At some point, surely, these adjustments should have sufficed to eliminate unemployment in so far as such unemployment might be attributed to a mere lack of spending.

And so, my question to the MM theorists: If a substantial share of today’s high unemployment really is due to a lack of spending, what sort of wage-expectations pattern is informing this outcome?

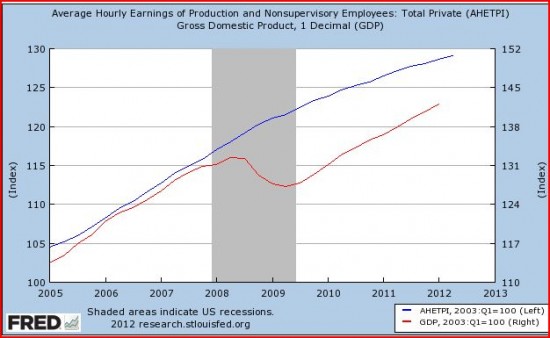

Let me admit right up front that the relatively slow adjustment of wages and prices is not 100% consistent with the natural rate model that I have in the back of my mind. Krugman has made the same concession. George was kind enough to send me a graph showing wage growth and NGDP growth over the last decade, which will help me to answer this question:

The unemployment rate peaked at 10% in 2009, and has since fallen to 8.2%. Notice that a huge gap opened between NGDP and wages in 2009, and that gap has partially closed. Just eyeballing the graph, it looks to me like perhaps 40% of the gap has closed. And that’s pretty consistent with the fall in unemployment from 10% to 8.2%, if you assume 5.6% is the natural rate. (I.e. a 1.8% drop is roughly 40% of the 4.4% drop needed.)

But George is right that there is another problem here; why haven’t wages adjusted more quickly? Recall that in the 1921 recession (caused by severe deflation) wages fell quickly, and employment grew rapidly after wages adjusted. What’s wrong with our modern labor market? Or is the market fine, but I’m in error assuming the natural rate model explains recessions? Here are some possible answers, none of which is completely satisfactory in my view:

1. Right before the recession Congress passed a 40% boost in the minimum wage, to be phased in over 3 years. This means that other wages had to fall just to hold the overall wage growth steady. Not a major factor, but it played some role.

2. The extension of unemployment insurance from 26 weeks to 99 weeks is (as far as I know) unprecedented in US history. It’s roughly the maximum level in Denmark. This presumably made workers a bit less desperate, and may have slowed the process of wage cuts. Note, this is completely separate from the normative question of whether the extended benefits were justified. My views on that issue are complicated, and I won’t get into them here.

3. There is powerful empirical evidence that there is money illusion at the zero wage rate increase point. Indeed George provides evidence for that sort of money illusion, when he notes later in his post that they’ve been given exactly zero percent wage increases at the University of Georgia for the past 5 years in a row. What are the odds that this was coincidence? I.e. what are the odds that in at least one of those 5 years the actual equilibrium wage change would have been minus 1% or minus 2%, and the administration decided to avoid wage cuts for contractual reasons, or morale reasons, or whatever. The survey data clearly shows the zero rate point is significant. Now some people argue that this shouldn’t matter, as the average wage increase is still positive, slightly under 2%. But that includes people working in healthy industries who are getting 4% increases, and other workers getting zero percent. It’s an average. So even at this level the zero boundary may be imposing some wage rigidity. Keep in mind it’s not that wages aren’t adjusting at all, the curve is clearly flattening, and the gap with NGDP growth is gradually narrowing. It’s just that the rate of adjustment is slower than expected.

I know that those three reasons won’t satisfy everyone, but they are the best I can do right now. And if I’m right that means that slightly faster NGDP growth would reduce unemployment by alleviating all three factors. It would reduce the ratio of the legal minimum wage to per capita NGDP. It would speed up the time in which Congress would bring maximum UI benefits down to 26 weeks (they have already started this process.) And it would reduce the “money illusion at negative nominal wage increases” problem. If wages are still above equilibrium, then even a fully expected boost in NGDP growth could reduce unemployment. If I’m wrong, it would merely lead to higher wage and price inflation.

I would add that David Glasner’s study of stock prices and inflation expectations suggests that markets think more NGDP and inflation would help right now, whereas during the 1970s I recall that inflation hurt the stock market. Indeed David showed that the stock market started rooting for monetary stimulus at roughly the point where market monetarists began to worry that money was too tight.

Because I think George’s point has some validity, I’ve gradually scaled back my calls for monetary stimulus. In 2009 I wanted the Fed to try to return to the previous trend line. Over the past year or so I’ve been calling for the Fed to try to go only about 1/3 of the way back to the previous trend line. That’s partly because some wage adjustment has occurred, and partly because even going 1/3 of the way back would call for significantly higher NGDP growth. Indeed if they even delivered 5% growth from here on out, with no trend reversion, I’d be pleasantly surprised . I read the markets as expecting closer to 4%, which is the actual rate over the last 7 quarters. (Oddly the quarterly growth rates have been eerily stable at about 1% per quarter.)

That’s my basic argument. But I would add that I see more downside risk to the global economy than upside risk. The US is so large that is has some influence on the global business cycle, and my hunch is that stimulus here could help the entire world economy at this moment.

Update: George Selgin had a follow-up post written before mine, but which I didn’t see until afterwards. I think our views are actually quite close.

Lars Christensen has a post replying to George that makes some excellent points, which partly but not entirely overlap with this post. I’d just like to clarify one point:

This is a tricky point on which the main Market Monetarist bloggers do not necessarily agree. Scott Sumner and Marcus Nunes have both strongly argued against the “Hayekian position” and claim that US monetary policy was not too easy prior to 2008.

I’ve probably left that impression, but I’d prefer to claim that I’ve argued “weakly against” the Beckworth view. I’ve occasionally acknowledged that NGDP growth might have been too high in the 2004-07 period, but I’ve also claimed:

1. It’s debatable, as under level targeting some catch-up from the previous recession was reasonable.

2. The excess NGDP and RGDP growth was unusually low for an economic expansion, and hence tells us little about the perception that our economy was in a sort of unsustainable bubble prior to 2008. But I’ve also been careful to acknowledge that David might be right about growth being somewhat too high.

I would add that it now appears the US trend RGDP growth fell to perhaps 2.5%, or even less during the early 2000s. This implies the housing boom was a bit more excessive than otherwise, as GDP was a bit further above trend than I initially realized. Now if the Fed was doing 5% NGDP targeting that fact would not matter, but because it was doing 2% inflation targeting, the drop in trend RGDP growth effectively made the overheating a bit more than I initially judged. Given what’s happened since 2008, it would have been better for the Fed to have had a bit tighter policy prior to 2007, aiming for a 4% to 4.5% trend line (but with level targeting to allow some catchup from 2001-02), and then a considerably easier policy after 2008, to have a smoother overall path in nominal aggregates. Even Christina Romer considers 4.5% to be the new trend line, and her overall views are quite “dovish.” She still favors full return to the previous trend.

Tags:

8. July 2012 at 18:36

FWIW, and IMO, this post is without a doubt the most thoughtful, most clear headed analysis of NGDP targeting as against criticism that I have ever read on this blog.

8. July 2012 at 20:04

Scott: this is a good reply to George. The first point is important. It’s the *threat* to expand the size of the central bank, *conditional* on NGDP being below target, that causes NGDP to rise, and shrinks the size of the central bank.

8. July 2012 at 20:12

Scott, Very interesting post, which I will have to reread to comprehend more fully than I could on a quick first take. Perhaps I will also try to respond to George on my own later this week, but the point he raises about the behavior of wages is one that I have also been wondering about. I mentioned it in passing in a recent post on W. H. Hutt and Say’s Law and the Keynesian multiplier (http://uneasymoney.com/2012/07/04/w-h-hutt-on-says-law-and-the-keynesian-multiplier/). I suggested the possibility that we have settled into something like a pessimistic expectations equilibrium with anemic growth and widespread unemployment that is only very slowly, if at all, trending downwards. To get out of such a pessimistic expectations equilibrium you would need either a drastic downward revision of expected wages or a drastic increase in inflationary expectations sufficient to cause a self-sustaining expansion in output and employment. Just because the level of wages currently seems about right relative to a full employment equilibrium doesn’t mean that level of wages needed to trigger an expansion would not need to be substantially lower than the current level in the transitional period to an optimistic-expectations equilibrium. This is only speculation on my part, but I think it is potentially consistent with the story about inflationary expectations causing the stock market to rise in the current economic climate.

8. July 2012 at 20:48

Scott, even before I had read the others’ takes on it, I too thought George’s post and your response here were very cool. I wish all internet econ debates could be like this. (Well, except that both you and George are wrong.)

Anyway, when you get a chance please clarify two things for me when you wrote:

(1) “I believe additional stimulus would actually reduce the Fed’s footprint on the economy.” This makes absolutely no sense to me. How are you defining “stimulus”? Wouldn’t it be more appropriate for you to say, “I am arguing for a change in the type, or the nature, of stimulus, such that I am actually asking for less than what Bernanke has already done” ? If a doctor starts amputating the left leg of a guy having a heart attack, is it really accurate for another doctor to say, “That’s inadequate medical intervention. That patient is going to die because his doctor isn’t doing enough for him”?

(2) “If I’m wrong, it would merely lead to higher wage and price inflation.” You act like this is no big whoop. Couldn’t every advocate of higher monetary stimulus, throughout human history, have said the exact same thing? And yet, for many of them, such a statement would have been incredibly flippant, right?

8. July 2012 at 21:16

George’s third question was my question, basically. I’m glad it finally got the answer it deserved (a post of its own) – though I’m still not quite convinced. I still think it’s the weakest point in the whole MM story.

8. July 2012 at 21:20

In defense of the MM view: http://mediamatters.org/research/2012/06/08/the-main-problem-with-jobs-growth-is-lack-of-de/185857

This really is a great post, even MF likes it.

8. July 2012 at 21:32

I would be far, far more aggressive in publicly targeting higher NGDP growth than Scott Sumner or Selgin. Just what are we afraid of? Inflation rates still lower than the 1980s, or during the robust 1982-2008 time frame, when they usually ran from 2 percent to 6 percent? Sheesh, we are generating a new dole class of early SSDI recipients. Time for growth!

On the Fed’s balance sheet? Who cares? Let the Fed hold the bonds until maturity. After buying a couple of trillion more. It is like retiring the debt, scott-free. Why not hand our children a deleveraged nation?

There is not a businessman in the world who would not seize this opportunity to retire federal debt without serious costs.

Some people (like Selgin) just can’t stand the idea of monetizing debt, as it seems sacrilegious, and sure to lead to hyperinflation. After $2 trillion of QE, we have the lowest inflation rates and interest rates since the 1930s.

Let us worry about the fine points of exceedingly esoteric economic theories later.

Now we should target robust growth. You know, people need jobs and business need profits. Oh, that.

There are reasons to believe, thanks to the global economy, the Internet, increasing productivity, and the lack of USA labor unions, that inflation is a diminishing threat, and has been for decades. Jeez, accept the good news and move aggressively forward.

8. July 2012 at 22:18

One consequences of persistent unemployment is that what might be called “competitive” supply narrows, as the insider-outsider gap grows, as Evan Soltas has pointed out nicely. That takes time to kick in, but it does mean the “natural rate” of unemployment increases just from having unemployment.

Secondly, the public sector is not so affected.

Also, it is mainly hirings which change over the business cycle. While private sector earnings growth does seem to be tracking roughly CPI. So, it seems employers are paying to keep the employees they have and they’re not leaving so much. Nominal wage stickiness is surely to a significant degree about preserving relationships with existing workers, so if those relationships are being “stretched out” that would slow down adjustment.

8. July 2012 at 22:19

One consequences of persistent unemployment is that what might be called “competitive” supply narrows, as the insider-outsider gap grows, as Evan Soltas has pointed out nicely. That takes time to kick in, but it does mean the “natural rate” of unemployment increases just from having unemployment.

Secondly, the public sector is not so affected.

Also, it is mainly hirings which change over the business cycle. While private sector earnings growth does seem to be tracking roughly CPI. So, it seems employers are paying to keep the employees they have and they’re not leaving so much. Nominal wage stickiness is surely to a significant degree about preserving relationships with existing workers, so if those relationships are being “stretched out” that would slow down adjustment.

(The comment with supporting links got shunted off to moderation.)

8. July 2012 at 22:25

+1 benjamin

8. July 2012 at 22:37

Bob Murphy: take a simple example. Suppose the only liability on the Fed’s balance sheet is currency. The higher is the inflation rate, the lower the real quantity of currency demanded, and the smaller is the Fed’s balance sheet as a proportion of the size of the economy. Tight monetary policy, and fear of deflation, would increase the real size of the Fed’s balance sheet.

8. July 2012 at 22:38

Also, the graph is of average hourly earnings, so any adjustment through reduction of hours would not show up.

8. July 2012 at 22:46

That graph doesn’t tell the whole story. Here is a Fred graph of not only GDP and hourly earnings, but also weekly earnings (hourly earnings* hours per week) and payroll on the same basis (hourly earnings * hours per week * people employed).

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=8zW

Blue line = GDP

Orange line = hourly earnings

Red line = weekly earnings

Green line = payroll (weekly earnings * number of employees)

Purple Line = GDP / payroll

All these are indexed with 01-01-2000 as 100 so they will be comparable.

It looks like employers don’t cut hourly rates because they don’t need to. They do fine controlling hours per week and number of employees. Wages are only part of the total cost of an employee. There are not only benefits, but HR costs, hiring and training costs and the lower productivity of a new employee.

It’s much more profitable to find a way to eliminate a job. The takeaway here may be that we’ve increased overheads to the point where we’ve tipped the balance between lowering salaries and eliminating jobs.

8. July 2012 at 22:53

I had to edit the graph above to add the gdp/payroll line, which seems to change the url. So for the 5 line version, it’s now:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=8A4

9. July 2012 at 01:15

Good post, and good questions raised by George Selgin.

One plausible explanation of the refusal of wages to fall might lie in the Fischer Black/ Tyler Cowen view of the world. No AD shock is disjoint from an AS shock. If you truly take capital to not just be buildings and factories, but simply (or also) be the present value of expected future earnings (as evidenced in asset prices), you will see a crash in asset prices (esp. home prices) not just as a wealth effect but also a supply shock in itself. ‘We are not as wealthy as we thought we were’. This supply shock would prevent a fall in wages (and also prevent deflation) and will keep unemployment high. It is isomorphic, in some situations, to ZMP workers. The MP of workers is not an immutable reality, but simply a belief, which has been revised given the shock to asset prices. Ergo, many workers previously thought to be worth something are now ZMP. This could even be the dominant explanation for an economy like the UK.

Another way to look at this data could be the Keynesian counterfactual. Instead of fretting, one should be glad that nominal wages have not fallen – a fall in nominal wages would have triggered a deflationary spiral and whatever positive AD growth the US has been able to maintain since the shock hit can in part be attributed to the rigidity of nominal wages. The involuntary unemployment will persist as long as the market rate of interest is higher than the natural rate, which is in all likelihood deeply negative at the moment.

Inflation (and inflationary expectations)- if not channelled into commodity prices – might still do the trick, combined with some form of indebtedness reduction for households. Nominal devaluations would work isomorphically as inflation expectations. In the absence of strongly negative interest rates, how does one go about doing it?

I see two ineffective ways, one probably effective but bad way and one good way to achieving a nominal devaluation/ inflationary expectations. QE and exchange rate pegs are the ineffective ways, credit/qualitative easing is the effective bad way and helicopter drops are the good way.

Large scale treasury purchases will probably be ineffective – the short maturities are interchangeable with ‘money’ (and have actually been interchangeable with money due to their role as collateral for a long time now anyway). The long maturities are held by investors that do not make much use for short term liquidity and buying them up in exchange for ‘money’ would probably do nothing apart from reducing their expected yield and causing negative wealth effects. (One could , however, simultaneously issue new longer maturity treasuries or expand the list of risk assets that pensions/ insurance funds are allowed to hold – this may yet work, but Operation Twists would almost certainly not)

Exchange rate pegs, ala Switzerland, would simply be a subsidy for those seeking safe assets. SNB’s Svenssonian resolve in maintaining the peg tends to get lionised, but people forget that SNB’s own prediction of consumer inflation for 2012 is -0.5% (rising slowly to 1% by 2014) and growth forecasts are under 1% (rising slowly to 2% by 2014). Their asymmetric inflation target allows them to escape notice on the fact they have essentially stabilized neither of the nominal anchors (price or income) that anyone cares about and are simply creating a massive run up in home/ financial asset prices (as denominated in CHF). Something very similar would happen to US if the Fed committed to an exchange rate peg. There is a small catch here – if an asset price decline could be seen as an AS shock, as I said in my first para, then this increase in USD asset prices could push down unemployment by reducing the number of ZMP workers, just like that. Indeed, the stability of the Greenspan era can be seen as a result of the Greenspan put on asset prices. The trouble with this system is that while it might stabilize AD, it promotes severe fragility, risk aversion, higher correlation and financialization. When the eventual bust comes again, it is bigger and harder than ever before. Still, might be worth trying, if it can be ensured that asset-owners do not internalize it.

Buying up risk assets (or expanding what is and what is not acceptable as collateral) is a bad way that might work. It would be inflationary, but would probably end up creating the mother of all moral hazards and increasing ‘financialization’ of the real economy. Risky assets may in the future be traded not on the basis of any analysis but simply on an evaluation of the implicit guarantee that may be extended to them in hard times, ala banks.

Helicopter drops *should* work – they repair the impaired household balance sheets, and by giving money directly to people bypass the concerns of ‘look at those politicians spending money on their favourite vested interests’. They also bypass a risk-averse and dysfunctional financial system that no longer seeks to allocate credit and make money through superior expertise at credit risk, but simply through carry trade arbitrages. You could have an increase in consumer spending while at the same time increasing the savings rate. And money-financing a fiscal transfer is the tried and tested method of creating inflation in all emerging economies. I’m not sure about the US, but the UK has a fairly efficient way already of implementing this there via the PAYE system, should they want to. Plus. everyone could go home claiming victory – who wouldn’t love a Friedman idea that the MMTers heartily endorse their own. The natural rate would probably climb back up, inflation expectations would rise, and the central bank would be able to stabilize AD at higher nominal rates and a smaller balance sheet (eventually).

In principle, any and all forms of nominal easing would work better if there was swifter principal forgiveness, i.e. mortgage restructurings.

And of course, communicating a firm resolve to do ‘whatever it takes’ wouldn’t hurt. My only contention is with the choice of actions that stands ready to support this resolve when needed – the Friedman/Sumner/Kimball bazooka is QE, and the Svenssonian bazooka is exchange rate pegs. I contend that helicopter drops are better than either.

And meanwhile, yes, CBs chould change their nominal anchor from prices to spending. In a world of imperfect CB control, NGDP targeting would be a better policy than IT, even if the CB was to fail in achieving it.

Sorry for the long, slightly digressive comment. I was just enthused by your acceptance of the failure of wages to behave as they might be expected to in your mental model.

9. July 2012 at 01:58

I really enjoyed this post. Though it seems the case for NGDPLT has more to do with just unemployment.

What I’ve been getting out of the debate is the main purpose of NGDPLT is to stabilize markets and thus the economy with some solid expectations about what the Fed will or won’t be doing. Right now, with variable inflation between 1-2% and various kinds of instability floating around the globe, no one really knows what the Fed response function is or if whatever kind of diving conditions from the tea leaves it might be doing will kick in in time to prevent the history from 2008 repeating itself, and it scares the pants off people who might otherwise invest in economic growth, which includes just about everyone along the growth chain from investors to hiring managers to consumers. With the current management processes going on at the Fed, it made itself a major source of uncertainty and NGDPLT will alleviate it.

I don’t think I’ve heard the argument that we should just go print a lot of money so the unemployed can find something to do. That would be inviting more trouble down the road, but it seems like that is what Seglin is making the NGDPLT argument out to be.

9. July 2012 at 02:01

[…] 2: Scott also has a comment on George’s posts. I think this is highly productive. We are moving forward in our […]

9. July 2012 at 02:42

I certainly agree with you that a large monetary base is not stimulus.

I guess implicit in arguments like Selgin’s is the idea that in the new normal this is the best we can do-maybe the “natural rate of unemployment”-I for one have issues with that idea, but never mind-is now 8% or close to it.

Again, while I know you may not be a fan of “class warfare” the fact it it’s much easier for people with high paying secure jobs to feel this way-‘the rest is just sructural unemployment’

for those unemployed or underemployed-it’s certainly cold comfort. To the contrary it tells you that the powers that be are totally sanguine about your position.

9. July 2012 at 02:43

Scott, I think David Glasner might have a point. In fact I think David Eagle have said a very similar think. Eagle attributes this to inflation targeting which in his view creates what he calls “price indeterminacy”. His is basically a expectational trap like the one David talks about.

9. July 2012 at 02:53

“Some people (like Selgin) just can’t stand the idea of monetizing debt, as it seems sacrilegious, and sure to lead to hyperinflation.”

Benjamin Cole reveals himself here as one of those people who’d rather not tangle with the ideas of a real human being, when it’s so much easier to win an argument with a cartoon!

9. July 2012 at 03:03

The U.S. economy was on a pretty stable growth path of nominal GDP during the Great Moderation. From 1985 to the end of 2007, the growth rate was about 5.4%. But what is important is that the growth path was stable. This isn’t just an average of growth rates over the period.

Anyway, if you really believe in level targeting, then returning to that trend growth path seems desirable.

Of course, there really wasn’t any commitment to that trend growth path. We had Greenspan’s support for vague price stability. And this may have even been responsible for some of the deviations we observed.

Anyway, I just don’t see how after a two decades of a 5.4% growth path, we look at where we dropped off of it, and then say this is a cyclical peak, where the economy is overheated.

Wages (of nonsupervisory and production workers) are 2.5% below their growth path. Prices (GDP deflator) are 2% below. Nominal GDP is 14% below.

Exactly where we are on other nominal contracts–long term debt–how much has been paid off, defaulted, or refinanced, I don’t know.

I still believe that the economy will eventually fully recover on a new growth path for nominal GDP, and even with a slightly slower growth rate.

But there is a long way to go (2% or 2.5% vs 14%.)

If everyone just ignores the growth paths and just looks at rates — that is 1.5% nominal wage growth, and 4% nominal GDP growth, why aren’t we “recovered?” Well, obviously the growth paths matter! And we are recovering.

9. July 2012 at 03:07

Bill, Greenspan actually supported a NGDP GROWTH target of 4.5% – see what he said in November 1992: http://marketmonetarist.com/2011/12/30/guess-what-greenspan-said-on-november-17-1992/

9. July 2012 at 03:43

Scott: Nice post. I would just add another possible reason why we do not have “full employment now”: Monetary Policy Uncertainty. People now know that there is a risk that CB will not offset nominal shocks to the economy. I would say that this is an “institutional” supply-side technology shock similar to the minimum wage or UI laws.

If correct monetary policy smooths out the business cycle having positive impact on the real economy, that has to mean that belief that we now have (or that we in the future could have with some increased probability) bad monetary policy has to have negative impact on the real economy. So this should impact on expectations of average real variables such as real growth and unemployment changing their long-term values over the business cycle.

9. July 2012 at 04:04

[…] asks what market monetarists think now that there is inflation and still no unemployment. Sumner responds. I don’t think this is quite fair; Sumner has been clear for a long while that he wants to […]

9. July 2012 at 05:00

George Selgin:

U.S. NGDP was restored to its pre-crisis level over two years ago. Since then both its actual and its forecast growth rate have been hovering relatively steadily around 5 percent, or about two percentage points below the pre-crisis rate.The growth rate of U.S. average hourly (money) earnings has, on the other hand, declined persistently and substantially from its boom-era peak of around 4 percent, to a rate of just 1.5 percent.** At some point, surely, these adjustments should have sufficed to eliminate unemployment in so far as such unemployment might be attributed to a mere lack of spending.

Do you actually believe that persistent unemployment is possible on the basis of “a mere lack of spending”? Or are you saying something like “even if we assume this theory is true for argument’s sake, my point is that the data shows that at some point unemployment will fall down to the natural rate”?

——-

In other words, if one person says unemployment can be reduced on the side of the state decreasing its presence by reducing labor market regulations to decrease money wage rates down to “uncontrolled” NGDP, while another person says unemployment can be reduced on the side of the state increasing its presence by using inflation to increase NGDP up to “uncontrolled” money wage rates, what is the logic for concluding that unemployment is caused by a reduction in NGDP, rather than by a failure of money wage rates to fall? [NB I reject the belief that more inflation can lead to less state intervention, since inflation is a state action, and state presence is a function of state action. If the state reduces its actions, then by definition the state has less presence.]

Why should we fight tooth and nail to get the Fed to increase inflation (and therefore NGDP) so that money production rises above what the free market rate would have been, instead fighting tooth and nail to get the state to eliminate all labor market regulations so that money wage rates are free to fall to their unhampered market rate alongside market driven NGDP?

Why does market monetarist “pragmatism” just so happen to coincide with more state action and more state presence all the time? At what point does this form of pragmatism become just regular socialism?

Why is the market monetarist solution to the unemployment problem a call to increase state action (inflation) and hence increase the presence of the state, rather than reducing state action (remove labor market regulations) and hence decrease the presence of the state? And why aren’t market monetarists calling for an actual market in money production? Isn’t the “market” in “market monetarism” an irony?

9. July 2012 at 05:06

George Selgin,

I wanted so much to respond at your site, and yet Benjamin’s support of the dual mandate here gives me a chance to put my thoughts into perspective. For nearly a decade I have worried about what was happening to the monetary system, and because of a long life of struggle, have figured out some of the things you are also concerned about. Something to consider: people such as myself are cheerleaders of the dual mandate because no other options exist yet. There are no public coalitions looking for long term economic solutions for those without economic access, no public online forums with ongoing discussions as to roadmaps for people without money. More importantly, some people will eventually need to move ahead in our country with very little money and right now no one is publicly speaking about how they might do so. That means no amount of focus, resolve, intelligence or skill can assist in survival, for those without money. That’s what we have to do something about. And because nothing publicly exists yet to help, market monetarism has been the last bastion of hope of unemployed people such as myself by default. People such as myself, Scott, Marcus Nunes, Benjamin Cole, Charger Carl and many others would not be such cheerleaders for the double mandate were it otherwise.

I would love to be able to study with someone such as you and work to better the system from the inside. However I am nearing sixty and discovered my math skills are too rusty, so I had to shift my focus towards recreation of knowledge based markets through psychological and social perspectives. When you spoke of limited raises for the past five years, for me it was like staring into the face of the sun, because I could not see any hope of that changing as directly paid knowledge work continues to decouple from knowledge assisted products manufacture in the near future. Know that I support your position, even as I stand for Scott’s which has become the last bastion of hope for many. And believe me, he too wishes it were otherwise, that is, he wants other people to be working on such solutions who have not yet stepped forward. May we all come together for those who can not realistically hope for monetary economic access in the future, so that their lives do not have to be wasted.

9. July 2012 at 05:39

David Glasner suggests “the possibility that we have settled into something like a pessimistic expectations equilibrium with anemic growth and widespread unemployment…To get out of such a pessimistic expectations equilibrium you would need either a drastic downward revision of expected wages or a drastic increase in inflationary expectations.”

The rub, if you ask me, is that of reconciling “pessimistic expectations” with what appears, on the face of things, to be an overly optimistic positioning of expected wages.

9. July 2012 at 05:48

George Selgin you said:

“Benjamin Cole reveals himself here as one of those people who’d rather not tangle with the ideas of a real human being, when it’s so much easier to win an argument with a cartoon!”

To be honest George I feel a lot of you guys aren’t willing to tangle with a real human being either if he’s not part of your elite Macro club-even if his ideas have merit.

Now I wonder what your response would be to my above comments which I’ll repreat:

I certainly agree with you that a large monetary base is not stimulus.

I guess implicit in arguments like Selgin’s is the idea that in the new normal this is the best we can do-maybe the “natural rate of unemployment”-I for one have issues with that idea, but never mind-is now 8% or close to it.

Again, while I know you may not be a fan of “class warfare” the fact it it’s much easier for people with high paying secure jobs to feel this way-‘the rest is just sructural unemployment’

for those unemployed or underemployed-it’s certainly cold comfort. To the contrary it tells you that the powers that be are totally sanguine about your position.

9. July 2012 at 05:50

My point George is that impolicit in your structural unemployment argument is that you are willing to write off millions struggling with unemployment as there being nothing that can be done.

Better they suffer than inflation rising a point.

9. July 2012 at 05:55

excellent post (and comments, naturally except for MF).

The good news though is that despite every attempt to dampen the housing market recovery by the Fed and the govt, there are some strong signs of life. Its been in a depression for a long time and has recovered without any help, so I doubt outside events like the Eurogeddon will hurt it much. My guess is that 18-24 months from now y’all will be calling for ngdp targeting to slow down the recovery.

which BTW, is a point that was not mentioned: the real (natural) rate of interest changes over the business cycle. back in 2009 it was probably deeply negative (meaning: we needed some significant depreciation of the housing stock). Now its much less negative. As properties move through the foreclosure pipeline they are depreciating faster than normal. 12 months from now we should see a recovery in construction jobs.

The fact that the natural rate is not only unknown but changes over the business cycle means to me that its very unlikely that the fed can hit a price level target with interest rates. Its like this: pick a random number between -5% and +4%, but don’t reveal it. Add 2%. without revealing the number, the Fed needs to adjust nominal rates to hit that number. Even worse, it changes periodically. Even if things are humming along swimmingly, it seems very likely that the fed will over or undershoot and will only know of that fact ex-post, when the economy was overheating. But it will not always bleed into inflation right away (in fact, its unlikely to given wage rigidities).

like i said, 24 months from now ngdp targeters will be looking for slower growth as money will be too loose. I think the Fed is going to get lulled into doing nothing because it keeps missing the forecast (i am not saying they should tighten now, just that inflation targeting via interest rates is doomed to make them slow to react).

9. July 2012 at 06:15

If I were a supporter of NGDPT I would see Selgin’s chart as supporting my world view. Wage rates kept on increasing at not much below trend despite NGDP falling significantly below trend. This gives a good explanation of unemployment since 2008. Assuming you can now get NGDP back on trend without significantly changing the wage rate trend – problem solved.

To me the bigger question is: Why is it like that ? Why is the supply if labor curve so inelastic. How did we get to this Keynesian paradise where the only variable that matters is what the CB chooses the level of aggregate demand to be?

I don’t want to live in a world like that – what do we need to do to get out of it ?

9. July 2012 at 06:18

“The good news though is that despite every attempt to dampen the housing market recovery by the Fed and the govt, there are some strong signs of life. Its been in a depression for a long time and has recovered without any help, so I doubt outside events like the Eurogeddon will hurt it much. My guess is that 18-24 months from now y’all will be calling for ngdp targeting to slow down the recovery.”

dwb, from your lips to God’s ears. Housing has certainly been recovering-though is it possible Eurogeddon could recover our reocvery? That it seems to me is the biggest worry.

18-24 months huh? I am thinking it woulb be a great time to bone up in say Bank of American stock-surely it won’t be a $6 stock forever with the housing reocvery

9. July 2012 at 06:18

Another part of an explanation for George Selgin may lie in how wages adjust, the renegotiation of contracts. Wage adjustment by contract negotiation becomes a slower process during nominal recessions, because opportunities to fully renegotiate contracts — actual separations from employment, whether a quit or a layoff — become scarcer as employees cling to their jobs. From the JOLTS survey, I was able to find that the mean duration of employment — the average amount of time before a separation — rose from roughly 27 months before the recession to roughly 32 months. (See graph: http://bit.ly/PFH47a) The actual real wage adjustment process seems to happen through the channel of paying fired workers substantially less in their next form of employment. For those who remain employed through a recession, there tends to be no wage adjustment process. It may follow, then, that an employment recovery would help reduce real wages — the unemployed aren’t counted in average wages. (See graph 1A in this paper: http://bit.ly/N9Lv7o) In short, the problem may be not only that slow adjustment in wages is preventing the labor market from clearing, but also that the labor market’s failure to clear is preventing adjustment in wages.

9. July 2012 at 06:20

MF, Good comments bring out the best in me.

Nick, I agree.

Thanks David, I’ve had similar thoughts, but I haven’t been confident enough to put them forward as a hypothesis. I differ slightly on one point–I think the graph shows wages are still a bit too high for equilibrium with NGDP. This is a tricky area, because the labor force has also declined, partly via people going on disability, partly due to emigration of Hispanic workers back to Mexico. So I may be wrong. Another issue is the rising rate of corporate profits. If that’s a trend unrelated to the recession, it forces the adjustment in wages to be even larger.

Bob, The monetary stimulus would be a commitment to faster NGDP growth. Once those expectations settle in, people and banks would be less interested in holding lots of zero interest base money. That’s a view that’s certainly consistent with Austrian econ. Recall Austrians fear that higher inflation leads to a flight from currency, and too much speculation. I don’t think we’d go that far, but to the extent NGDP growth expectations rise, there is less demand for base money. That also means no need for “unconventional” asset purchses, the Fed could stick to garden variety T-securities.

Regarding your second point, you are right. I misstated what I was trying to say. I meant “merely” not in the sense of “no problem” but rather in the sense of “inflation is all we’d get, not the real growth we hoped for.” Poor choice of words on my part.

Saturos, Thanks. I’ve actually done this before, several times–but probably before you started reading the blog.

To me it’s mostly important as a transition issue. Once we settle in to NGDP targeting, we don’t need to worry about how much of the unemployment is cyclical.

Yes, that’s a good post you linked to.

Ben, I consider Selgin one of the good guys, regardless of slight differences in interpretation.

Regarding my views, if we committed to going one third of the way back to the old trend line, it would do much more than you might assume. That’s because a lot of wage reduction has occurred, so we don’t need to get to the old NGDP trend line to get roughly back to full employment.

Lorenzo, Excellent comment; I hope others read it. You could do a better job than I at explaining the labor market anomoly.

Peter N, Weekly wages might be distorted by the fact that people work less hours per week during a recession. That’s why hourly wages are the best test of the sticky wage hypothesis.

Ritwik, A lot of points, here’s a few reactions.

1. I’m skeptical of the ZMP hypothesis, but it might be a contributing factor.

2. Strongly disagree on wage rigidity. Hoover tried that in the early 1930s and it was a disaster. Falling wages boost AS, they don’t affect AD at all. They are expansionary.

3. Regarding the SNB, I agree that fixed exchange rates are not optimal. In fairness, they have 3.4% unemployment, so their economy seems used to near-zero inflation. They are doing fine.

Bonnie, I agree about uncertainty.

Lars, I don’t think a drastic rise in inflation is necessary, although that seems to be Krugman’s view. I think even 2% inflation, level targeting, would help a lot. (Obviously I prefer NGDP over inflation.) Inflation has average 1.1% since July 2008—where would we be if it had averaged 2%.

Bill, If the Fed had been targeting NGDP growth, I’d totally agree. But they were actually pursuing a target path that was slowly falling–more than 5.4% early on, less than 5.4% later. That’s for two reasons. RGDP trend growth was slowing, and also the Fed reduced it inflation target from 2% to 3%, to simply 2%. This means that by 2007 we were probably above the Fed’s slowly falling target path. Of course I think the Fed was wrong to do things that way, they should have a stable target path, as you and I advocate.

JV, Maybe, but I’m skeptical that that is a big factor. I’m actually pretty confident NGDP will keep growing at around 4%, or at least as confident as I was during the Great Moderation.

9. July 2012 at 06:23

the only German economist worth his pay:

http://www.businessinsider.com/goldman-jan-hatzius-explains-the-real-issue-with-more-fed-easing-2012-7

still firmly in the ngdp targeting camp.

9. July 2012 at 06:30

dwb, Good observations. But I’m sticking to my forecast that rates will stay surprising low indefinitely. We were near the zero bound from 1931-51, it could happen again (although I think more likely we’ll bounce up to 2% eventually.)

Ron, Good point. I believe George conceded that it supported one part of my argument–wage stickiness was a problem when NGDP plunged and recovered slowly, but then he pointed out it raises the question of why it took so long for wages to adjust. It’s that second question that is the most difficult. I had a few ideas, and commenter Lorenzo (above) has some more good ideas.

Evan, Good point, but I wouldn’t push that quite so far. There is certainly some wage adjustment for continuously employed workers–George mentioned the zero percent raises at UG. Some employmed workers (not many) even take pay cuts. But I agree it’s mostly with new jobs, and churning falls during recessions. So that does explain part of the story.

FWIW, I believe Bentley had one year of zero percent increases, and three 2% to 2.5% increases, whereas 4% had been our norm.

9. July 2012 at 06:30

18-24 months huh? I am thinking it woulb be a great time to bone up in say Bank of American stock-surely it won’t be a $6 stock forever with the housing reocvery

stay diversified: the banks are still going to be weighed down by regulation, BASEL MCMXVLII, housing recovery will not help them (a lot of foreclosures are going to cash investors). Homebuilder stocks already reflect my optimism. you will always do better with a diversified prtfolio of etfs than overweight in this or that stock.

http://finance.yahoo.com/echarts?s=XHB+Interactive#symbol=xhb;range=20090109,20120709;compare=xlf;indicator=volume;charttype=area;crosshair=on;ohlcvalues=0;logscale=off;source=undefined;

9. July 2012 at 06:34

dwb, That’s a good Hatzius interview.

Everyone, I added an update at the end of this post earlier today. This who read it last night might want to take a look.

9. July 2012 at 06:35

My input in one picture:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/07/09/the-message-comes-out-loud-clear/

9. July 2012 at 06:39

Scott so is it just your thing now to ignore my comments-I don’t think you can accuse me of being overly long, or needlessly obnoxious.

9. July 2012 at 06:42

But I’m sticking to my forecast that rates will stay surprising low indefinitely.

indeed, they seem likely to (thats my basic point). rates staying low indefinitely does not mean ngdp growth stays low, or that we stay on the recent trend.

9. July 2012 at 06:49

I have only skimmed the comments, but I did not see anyone questioning why one would use the Average Hourly Earnings of Production Workers for the wage index. Since 2006 BLS has produced the Average Hourly Earnings of All Employeees which is has more comprehensive coverage than production workers only. Using the production workers index you are basically looking at the manufacturing sector only and throwing out every other sector of the economy. The service industry is a very important aspect of the economy and should not be discarded, hence the All Employee wage index should be used. The only problem with the All Employee index is that it has only been produced since 2006, but this should be sufficient for our purposes.

The link compares the Average Hourly Earnings of All Employees index and the GDP index:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=8As

Using the All Employee wage index compared to the GDP index one can see that the gap has nearly disappeared. I would say that the wages have completely adjusted especially if you extrapolate the GDP data to 2 quarter. Given that wages have now completely adjusted, it would seem that George is right that additional stimulus to the growth in nominal spending would have little impact on the labor market.

9. July 2012 at 06:51

The trouble with ETFs dwb is that they offer less bang for your buck-my trouble is I remember the halcyon days of 2008 where you could make 400% on options in the bank stocks-buying puts.

I always end up wanting to swing for the fences. Actually we’re back in the age where buy and hold works. I remember on Fast Money in 2008 they were saying it was dead. Since then if you did you’d be in good shape.

I still have to think that at some point Bank of America will be even a $15 stock again like it was in just 2010.

9. July 2012 at 06:53

What I find depressing is that the answers to the question ” why don’t start-up businesses hire the unemployed at a lower wage rate and undercut the competition” amy be “they can’t find anyone to work for lower wages than they earned before ” .

To David Glasner’s point: The pessimistic thing is that despite evidence to the contrary everyone acts like they are confident about the future and therefore won’t take lower wages. Is this a side-effect of 25 years of the “great moderation” ? Are NGDPTers just helping to continue this false optimism and what we actually need to get out of this recession is a health dose of pessimism about the future ?

9. July 2012 at 07:09

ssumner:

MF, Good comments bring out the best in me.

Good comments…from certain people. Not from me.

I’ve made the exact same argument Selgin made in June 2012, when I said :

“I think market monetarists have to be honest and say that they are now getting what they wanted. Yes, it’s not level targeting, but I would argue enough time has passed to adjust the entire price level, of wages, factor inputs, and outputs, downward from where it otherwise would have been had level targeting persisted.”

And what was your response? You came back with this patronizing vitriol:

“You’ve been here for years, and you’ve learned NOTHING? You still don’t even have a clue, do you? Levels, levels, levels, levels…”

Why does Selgin, who made the exact same argument, not get the “you don’t have a clue” response, but rather:

“I think George’s point has some validity, I’ve gradually scaled back my calls for monetary stimulus….Over the past year or so(!) I’ve been calling for the Fed to try to go only about 1/3 of the way back to the previous trend line.”

???

——–

This is not the only example, by the way. There are more. It’s just that up to this point I didn’t want to bring them up so as to not embarrass you in this way, but you just convinced me that you are more concerned with appearances than you are with ideas, and that explains why you care more about politics than you do about economics.

So if that is the game you want to play, if it’s appearances, then I will make you “appear” as intellectually unfair, so that you can finally do what I thought you always would have done on your own, which is address the ideas as they are, not who they are from.

9. July 2012 at 07:18

I still have to think that at some point Bank of America will be even a $15 stock again like it was in just 2010.

i have a long list of stocks that people have told me “I still have to think that at some point zzz will be even a $yyy stock again”

how about YHOO at 120. more recently C, or AIG.

nope. i’ve learned many times the hard way that you get what you pay for. cheap merchandise is cheap for a reason.

without going into mind numbing details, there are many good reasons people are staying away from banks these days. Even Wells Fargo and US Bancorp, which are in better shape than most, I would still not say are likely to outperform. Wells Fargo is well positioned to originate mortgages, but regulation and other stuff will still weigh.

http://finance.yahoo.com/echarts?s=WFC+Interactive#symbol=wfc;range=2y;compare=bac+jpm+xlf+gs+^w5000+usb;indicator=volume;charttype=area;crosshair=on;ohlcvalues=0;logscale=off;source=undefined;

most people have far fewer $$ allocated to bonds than they should already (which is no shocker in a low yield world). options kill you with transaction fees and a bid-ask of upwards of .75 for some illiquid ones. if you want “bang for your buck” (ie leverage or high beta) you can be overweight equities, high yield bonds small caps, REITS, commodities, all through ETFS which have low transaction fees. There are some double long/short ETFs too, which give you the leverage of options without the transaction fees. there is no shame in wanting a higher beta more aggressive portfolio, but there is no reason to pay the man via transaction fees.

9. July 2012 at 07:20

the yahoo link does not work, the 2 year comparisons are:

wfc

bac

jpm

xlf

gs

^w5000

usb

http://finance.yahoo.com/echarts?s=WFC+Interactive#symbol=wfc;range=2y;compare=bac+jpm+xlf+gs+^w5000+usb;indicator=volume;charttype=area;crosshair=on;ohlcvalues=0;logscale=off;source=undefined;

9. July 2012 at 07:46

Scott and/or George,

One thing I don’t understand is that George seems to imply that he would be in favour a 4% nominal wage target (growth rates not levels).

“Most of us (myself included) will also readily agree that, if equilibrium money wage rates have been increasing at an annual rate of, say, 4 percent (as was approximately true of U.S. average earnings around 2006), then an unexpected decline in that growth rate to another still positive rate can also lead to unemployment.”

But if this is the case, how could he not be in four of more monetary stimulus now when nominal wage growth is growing at the slowest pace since 1938? Average hourly earnings growth is currently just 1.5% y/y. Also, since wage growth is very sticky, the probability that the Fed would overshoot 4% wage growth over the 18 months is extremely remote.

To me, it’s the sluggish pace of nominal wage growth that is the key indicator of the need for Fed action. If nominal wages had been growing at a steady pace of 4% over the past 4 years then I would be very skeptical of the need for additional monetary stimulus. But the absurdly slow pace of nominal wage growth cinches the argument for me. I suspect the same might be true of others who are supporters of the market monetarists.

Of course, if nominal wages are the key indicator, this raises the question of whether nominal wages should be the target variable.

9. July 2012 at 07:52

The thought processing on this post (thus far and mostly!) is what I wish a lot of our petty political processes could be replaced with.

Evan Soltas, your April 30th, 2012 post “Locked Out: Labor Markets are Healing in the U.S. but Not For Outsiders” is really good.

9. July 2012 at 08:06

dwb, commodities of course have a good bang for your buck-though of course there are high margin requirements-I’ve never done it. I’d figure you have to already have money to play with for that.

Actually what could be interesting is currency. If you think Europe finally has its act together then maybe by the euro. If you don’t then continue to short it.

Actually all commodities in the US are procylical and have been for a long time-since about 2003.

People think oil going down is a good thing but it means the economy is weakening. And gold actually acts like just another commodity these days-nothing to do with Ron Paul reasons when it goes up.

9. July 2012 at 08:10

Still dwb you may be right about the double ETFs I haven’t really looked into those.

9. July 2012 at 08:11

Mike Sax, allowing that my argument amounts to saying that the “natural rate” of U is a very high 8%, you make two related, false assumptions. First, you assume that “natural” means OK, jolly, fine, ideal, or some such thing. That’s a canard. To claim that any rate of unemployment is a “natural” rate is merely to suggest that it’s underlying determinants are real, rather than monetary. This brings me to the second wrong assumption, which is that monetary expansion is always an effective means for combating unemployment, so that anyone who every opposed such expansion must not give a toss about the unemployed. In fact, as anyone conversant with the experience of the 60s and 70s will realize (and I fear that now many people are not), when monetary expansion is resorted to as a means for trying to lower “natural” unemployment, it not only fails to achieve its intended purpose, but ultimately does more harm all around, in part by ultimately generating even more unemployment.

In short, to suggest that high unemployment warrants monetary expansion even when it is “natural,” and that anyone who suggests otherwise must be indifferent to the plight of the unemployed, is like arguing that a doctor who refuses antibiotics to patients afflicted not by some bacteria but by a virus, must be indifferent to the plight of the diseased.

Gregor, you are incorrect in your inference concerning optimal wage growth, for while I believe that an unexpected reduction in equilibrium wage growth from 4% to something lower would result in greater unemployment, I also believe that a predictable, steady reduction from 4% to something much closer to zero would ultimately prove beneficial.

9. July 2012 at 08:25

@mike sax,

commodities of course have a good bang for your buck-though of course there are high margin requirement

everything has an ETF or ETN these days, including commodities ETFs which track the a commodites index or producers. have to be careful about tracking error and some other things, but most people do not have a margin account with the CME.

9. July 2012 at 08:47

Scott,

I am totally confused. As I understand it you have always called for the Fed to guarantee (or promise) NGDP growth at 5%. According to Selgin they have been delivering this;

“U.S. NGDP was restored to its pre-crisis level over two years ago. Since then both its actual and its forecast growth rate have been hovering relatively steadily around 5 percent”

You don’t challenge his assertion, but apparently you still think that the Fed should be doing something different than they are. Clearly I am missing something. I feel like Emily Litella.

9. July 2012 at 09:03

Mike, I think Scott’s new thing is to finish his book, which we should all get behind.

9. July 2012 at 09:05

Scott, doesn’t your theory have the same problem in explaining why Japan has stagnated for so long?

9. July 2012 at 09:26

Scott,

What does it matter if the economy was “overheating” if you don’t believe in bubbles? The only reason above trend growth should matter is if it dampers future growth, right? Isn’t this what people casually refer to as a collapsing bubble?

9. July 2012 at 09:34

DWB,

I was thinking the same thing you were about the leveraged ETFs and I asked one of my friends who runs a hedge fund what he thinks about them. He said that they don’t track properly by overshooting on the downside and undershooting on the upside. The only people who can benefit from them are day traders if they’re willing to take the risk of buying something that won’t track properly.

9. July 2012 at 09:36

At times like the present, “reasoning” has no bounds. From Posner:

“Still, the economy has righted itself to the extent that it is no smaller than it was before the crash; the contrast in this regard between 1929-1933 and 2008-2012 is reassuring. But how is it then that less labor is being employed? One possibility is that the shock of the crash accelerated a trend toward more efficient use of labor, as a result of greater automation (with low interest rates reducing the relative cost of capital expenditures and thus encouraging the substitution of capital for labor) and improved techniques of selecting and supervising employees”.

http://www.becker-posner-blog.com/2012/07/why-is-job-growth-tepidposner.html

9. July 2012 at 09:55

Agreed I’m looking forward to Scott finishing his book. If I’m wrong to personalize it apologies-everyone takes things personally sometimes!

9. July 2012 at 09:59

George Selgin –

“The first, more philosophical reason is that I think the Fed is quite large enough-too large, in fact, by about $2.8 trillion, about half of which has been added to its balance sheet since the 2008 crisis. The bigger the Fed gets, the dimmer the prospects for either getting rid of it or limiting its potential for doing mischief. ”

I’m not sure why anyone should care if the Fed’s balance sheet is “too large” – or what standard you would use to determine that. I’m against big government because of the cost to taxpayers. But a big Fed balance sheet saves the taxpayer money. I’m also against big government because it distorts the private economy. But the Fed holding Treasury bonds doesn’t distort the economy. It’s just trading one government liability (a Federal Reserve Note or Deposit) for another (a Treasury Bill or Bond). I could also see opposing expanding the balance sheet for fear of high inflation or NGDP growth, but that begs the question of what the target or standard is. We should base the balance sheet on the target. You’re turning it around and saying we should have a lower target because the balance sheet is too high.

It would make no difference if the Treasury issued currency directly (US Notes) or traded currency for commodities, you’d still have the same issues.

If the Fed can buy up the entire publicly held debt without exceeding our NGDP target we should be dancing in the streets in jubilation.

9. July 2012 at 10:00

My point I guess comes down to this I guess George. To think that the natural rate is this high is pretty pessimistic. And effectively it leaves us with nothing to do or give the unemployed much hope really.

Is there anything that you could suggest at all if this is the case?

9. July 2012 at 10:03

“I could also see opposing expanding the balance sheet for fear of high inflation or NGDP growth”

Of course, Negation, this begs the further question as to whether or not simply expanding the monetary base actually increases inflation or is in itself stimulus.

9. July 2012 at 10:14

Mike, although I’m far from being fully convinced that 8% is the “natural” rate, I suspect that a substantial chunk of it reflects structural unemployment connected to the collapse of the housing and financial sectors and associated businesses. Policies that seek, as some recent ones have done, a solution in “reviving” those sectors, and housing especially, as if employment levels in them ca. 2007 represented a healthy and sustainable ideal, only serve to discourage needed reorientation of capital and labor. Stabilizing NGDP isn’t itself at fault here, but other policy utterances may be contributing to a larger than usual hysteresis effect.

9. July 2012 at 10:24

John, bubbles are about asset prices being consistently and irrationally above levels justified by the true forecast of their fundamentals. Booms are about a temporary surge in real output above its long run trend (whether due to AS or AD; ie real or nominal factors), which need not be accompanied by an asset price bubble where people lose money.

9. July 2012 at 10:25

Paul Krugman on contractionary devaluation:

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2012/07/paul-krugman-on-contractionary-devaluation.html

And can any of the Austrians here explain how Hayek was justified in saying this: http://coreyrobin.com/2012/07/08/hayek-von-pinochet/ ?

9. July 2012 at 10:46

Hayek: What I want to discuss is policy in the long run””by which I mean not only the very long run in the Marshallian sense, but policy over the next few years. What we should absolutely avoid is any attempt to recreate employment, or diminish unemployment by a further dose of inflation.

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=15157#comment-167552

9. July 2012 at 11:08

Tom Dougherty wrote;

‘Since 2006 BLS has produced the Average Hourly Earnings of All Employeees which is has more comprehensive coverage than production workers only.’

Good point. The reason given for the change by BLS was that more and more survey respondents didn’t know how to identify ‘non-supervisory’ employees. They thought they were missing some important part of the labor force with their old stat.

9. July 2012 at 11:13

Saturos, I have answer for you: http://marketmonetarist.com/2012/07/09/you-might-know-the-words-but-do-you-get-the-music/#comment-5434

9. July 2012 at 11:24

Saturos, everybody knows that I am no Austrian, but I hold Hayek in very high regard and I think this is complete slander. The headline in the comment says it all – it is ridicules.

9. July 2012 at 11:27

See this link for an analysis based on George’s own theories that came to same conclusion as George’s recent post (and was published last December).

http://liquidationist.blogspot.com/2011/12/free-markets.html

9. July 2012 at 11:41

Lars, so are the quotes false or misinterpreted in that post?

9. July 2012 at 11:52

Dougherty:

I don’t use the broader measure of wages because I want to look at the trend during the Great Moderation. You need data from 1985 to 2008 to do that.

9. July 2012 at 11:57

After reading Tom Dougherty and Patrick Sullivan’s comments about the change in BLS from production workers to all employees I now have some questions as to whether this may have been partially responsible for derailing NGDP in some way. The change in 2006 seemed somewhat random, and one hopes it was better thought through than identification of non-supervisory employees, because the trajectory of those categories runs quite differently.

9. July 2012 at 12:01

Saturos, I have never personally read any comments from Hayek on Pinochet so I have no clue whether they are true or false. However, the idea that Hayek was some sort of crypto-fascist is simply too stupid for me. Hayek was a champion of liberty and few did so much as him to further the course of freedom as he did.

But enough from me on this…I hope somebody with greater knowledge Hayek’s works will respond to this.

9. July 2012 at 12:04

dwb:

excellent post (and comments, naturally except for MF).

Mmmmm, how does Sumner’s boots taste? You even mimic his verbiage dude. Where’s your integrity? Your originality?

My posts are far more informative, trenchant, and informed than yours.

Nick Rowe:

Suppose the only liability on the Fed’s balance sheet is currency. The higher is the inflation rate, the lower the real quantity of currency demanded, and the smaller is the Fed’s balance sheet as a proportion of the size of the economy. Tight monetary policy, and fear of deflation, would increase the real size of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Notwithstanding the fact that the Fed doesn’t just own currency, but also mortgages, government debt, and gold as well, which makes this supposition rather moot…

So if the US economy grew 100 times bigger compared to some status quo, that should the government also grow 100 times bigger, small government types should be more happy with that, than a situation where the economy grew only 50 times, but the state did not grow at all, because at the end of the day, the government is relatively smaller vis a vis total spending, as opposed to absolutely smaller?

The way to smaller government is not growing the economy and keeping the government. We tried that in 1776. Small absolute government and small government relative to economy, ended up turning into the world’s largest absolute government.

How? The economy was the government’s food. We can never “grow our way to smaller government”. A bigger economy serves as more food to allow the state grow. It’s like believing one can grow their bodies to shrink the relative size of their cancer tumors.

Even initially tiny, infinitesimally small government, because it is a monopoly on coercion and violence, will tend to grow in absolute terms, and usually faster than the rate of economic growth. It can grow faster in relative terms precisely because it is smaller in relative terms, and its faster than economic growth rate can still enable economic growth in absolute terms to take place. As this happens, we of course hear endless mantras from “progressives” that the 2% absolute growth is due to the wonderful government policies of increased inflation and spending.

Take a look at the growth in the size of our government since 1776, and the relative increase in government size post WW2. We are not having a lack of money printing problem. We have a philosophy of government problem.

9. July 2012 at 12:31

OT: This is not monetary policy related but Krugman has a post up today that just floored me. The topic is his typical bashing of the rich, but in it he says something that stunned me. And since I respect Krugman, I can’t just dismiss it outright.

“Now suppose that President Obama has reduced Mr. Wheelerdealer to despair; not only does the president waste money by doing things like feeding children, he says mean things about some rich people, which is just like the Nazis invading Poland, or something. So Wheelerdealer decides to go Galt. Well, actually just one-third Galt, reducing his working time to just 2000 hours a year so he can spend more time with his wife and mistress.

According to marginal productivity theory, this does in fact shrink the economy: Wheelerdealer adds $10,000 worth of production for every hour he works, so his semi-withdrawal reduces GDP by $10 million. Bad!

But what is the impact on the incomes of Americans other than Wheelerdealer? GDP is down by $10 million “” but payments to Wheelerdealer are also down by $10 million. So the impact on the incomes of non-Wheelerdealer America is … zero . Enjoy your leisure, John!

This stunned me. What he is in fact saying is that no one else’s work provides any benefit to me except mine own. If everyone else in the world stopped working, this would not affect me at all as long as I keep working. Paul Krugman has just tossed out the entire concept of Division of Labor!!

Am I missreading this in any way??

9. July 2012 at 12:33

Saturos:

And can any of the Austrians here explain how Hayek was justified in saying this: http://coreyrobin.com/2012/07/08/hayek-von-pinochet/?

Maybe Hayek was thinking the same way FDR did towards Mussolini.

I don’t much value Hayek, because of his social democratic bent, and thus penchant for tolerating violence to achieve “social ends.”

9. July 2012 at 12:36

dwb you may have given me some good investment advice-LOL. How exactly do you play a double etf though? How do you make the big move on it?

I’m not familiar with how they work

9. July 2012 at 13:03

“But George is right that there is another problem here; why haven’t wages adjusted more quickly?”

Maybe they have,… and something else caused the dip.

9. July 2012 at 13:33

I agree that this is a useful post. Choosing the path of NGDP to target is vital to ensuring that, if NGDP targeting is adopted, it is adopted for the right reasons.

9. July 2012 at 13:37

How exactly do you play a double etf though? How do you make the big move on it?

well, i do not advocate timing. the market will go up if nominal gdp grows faster and go down if it grows slower, and most stocks right now are pretty significantly correlated to a major index (like S&P, russel 2000, wilshire 5000, emerging markets index), etc. about 5000 hedge funds have algorithms scouring for alpha just now so i highly doubt you will find any. Not even the FOMC members themselves know whether QE is in the cards, but that and Eurogeddon will drive the market.