What’s wrong with Britain?

First a small point. Why is it so hard to find NGDP data for Britain? There’s been lots of press coverage of the 0.8% (annual rate) decline in RGDP during the 4th quarter, but I can’t find the NGDP data. Without NGDP data, RGDP is hard to interpret. “Never reason from a quantity change.” Of course that doesn’t stop people from doing just that, and in fairness the most likely explanation for the low RGDP is inadequate demand.

Some are now forecasting that Britain will slip into a recession next year. If America was expected to slide into recession next year due to insufficient demand, you’d see articles bashing Bernanke and the Fed all over the blogosphere. I’m not seeing articles bashing the Bank of England. Why not?

[Yes, there weren’t any articles bashing the Fed for tight money as we slid into our 2008 recession, but that was before the rise of market monetarism. They’d never again get away Scott-free. :)]

Perhaps it’s the stoic attitude of the British. (“Mustn’t grumble.”) But I am seeing article after article claiming that the coming recession is due to fiscal tightening. I was curious to see just how tight British fiscal policy actually is, so I checked the “Economic and Financial indicators” section at the back of a recent issue of The Economist. They list indicators for 44 countries, including virtually all of the important economies in the world. Here are the three biggest budget deficits of 2011:

1. Egypt 10% of GDP

2. Greece: 9.5% of GDP

3. Britain: 8.8% of GDP

Egypt was thrown into turmoil by a revolution in early 2011. Greece is, well, we all know about Greece. And then there’s Great Britain, third biggest deficit in the world.

I suppose some Keynesians work backward, if there is a demand problem it must, ipso facto, be due to lack of fiscal stimulus. If the deficit is third largest in the world, it should have been second largest, or first largest.

A slightly more respectable argument is that the current deficit is slightly smaller than in 2010 (when it was 10.1% of GDP.) But that shouldn’t cause a recession. Think about the Keynesian model you studied in school. If you are three years into a recession, and you slightly reduce the deficit to still astronomical levels, is that supposed to cause another recession? That’s not the model I studied. Deficits were supposed to provide a temporary boost to get you out of a recession. At worst, you’d expect a slowdown in growth.

To get a sense of just how expansionary UK fiscal policy really is, compare it to France (5.8% of GDP), Germany (1.0% of GDP), or Italy (4.0% of GDP). Lots of people blame ECB policies for the recession, but Britain is not in the eurozone. Outside the eurozone you have Denmark (3.9% of GDP), Sweden (zero), Switzerland (1% surplus).

Obviously there must be some problem in Britain that isn’t affecting some of its more prosperous northern European neighbors. I suppose if you are a Keynesian you’d say that the housing/banking problems in Britain were worse, and hence you need more fiscal stimulus than Germany or Sweden. Fair enough, but if deficits are already near the largest in the world, trailing only Egypt and Greece, you’re taking a pretty big gamble to commit to an indefinite number of years of even more massive deficits in the hope it won’t be negated by slow NGDP growth produced by the BOE. After all, debts do need to be repaid (or at least serviced.) And the taxes required to service the enlarged national debt will eventually impose significant deadweight costs on the economy.

In contrast, monetary stimulus is costless, and indeed improves public finances by reducing the debt/GDP ratio. So why aren’t people demanding more monetary stimulus? In America, my conservative commenters tell me the liberal Keynesians have a hidden agenda to boost the size of the state. But the British government is already nearly 50% of GDP, with national health care for all. So that can’t be the reason. Some claim that when rates are near zero it’s impossible for the central bank to devalue its currency. But didn’t the Swiss National Bank recently puncture that theory?

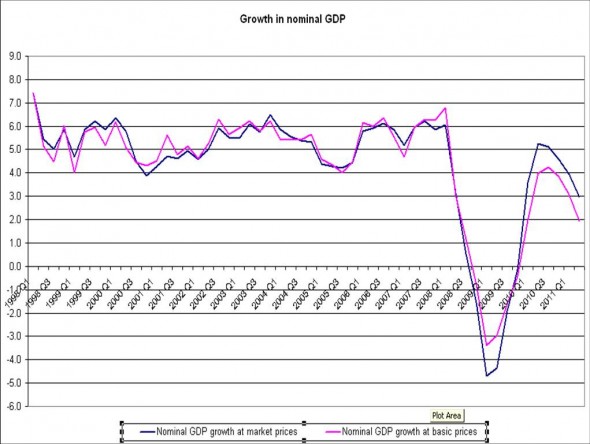

My hunch is that the BOE has gotten a pass because of fear of inflation, which was quite high during 2011. But that would suggest Britain’s problems are supply-side, not demand-side. Of course fiscal policies like the recent increase in the VAT also affect the supply-side of the economy, but as this Financial Times graph shows, that doesn’t seem to be the main problem:

Following the latest national accounts revisions, one worry is that the year-on-year growth in nominal GDP in the second quarter was only 3 per cent. Low nominal growth implies semi-fixed cash variables such as public spending, borrowing and debt become a larger share of GDP when the denominator is growing slower than was expected. But that is not all, as the following chart shows.

Until the crisis, Bank of England monetary policy appears to be remarkably successful in keeping nominal GDP growth close to 5 per cent. It almost appears to be the target the Bank was following.

Then in the crisis nominal GDP plunged, but note that the fall in nominal GDP at market prices is greater than that at basic prices due to the temporary cut in value added tax to 15 per cent. Since the basic price adjustment abstracts from taxes and subsidies, the standard nominal GDP variable now stands higher than the basic price version, since it includes the rise in VAT to 20 per cent.

Strip out the VAT rise and underlying nominal GDP (at basic prices) grew by 1.9 per cent – split into 1.4 per cent inflation and 0.5 per cent growth. Worrying about inflation in this climate is crackers…

Unfortunately this data is out of date, but my hunch is that the 3rd and 4th quarter NGDP data isn’t much different. This graph shows a big fall in NGDP producing a big recession in 2008-09, and presumably the smaller recent drop in NGDP growth will lead to a much smaller recession in 2011-12. The FT then hints the BOE is allowing this because of a fear of inflation.

Here’s where fiscal policy really may play a role. The VAT increase seems to have opened up a 1.1% NGDP gap between the expenditure of the public for final goods, and the net revenue received by firms. But even gross revenue growth is falling sharply. If the BOE was still targeting 5% NGDP growth, the VAT increase would not trigger a recession—3.9% more net revenue would probably be enough to avoid that outcome. Instead you have the BOE sharply slowing headline NGDP growth, and then the fiscal contraction reducing net revenue by another 1.1%. It seems the combination will be enough for a mild recession.

Keynesians are focusing on the fiscal part of the problem, but with Britain already having the third biggest budget deficit in the world, I think people need to start paying more attention to errors of omission by the BOE. That’s the elephant in the room that almost everyone is ignoring.

And someone tell the British to start making NGDP data easier to find. You can’t calculate RGDP without knowing NGDP, so there’s no excuse for not publishing the data.

PS. The October 2011 FT article was entitled “A Nominal GDP Nightmare.” Bingo.

Tags:

29. January 2012 at 08:15

Excellent post. So many people here in the UK are trying to attribute the difference between the US’s recent growth and the UK’s contraction to the difference between American “stimulus” versus British “austerity”!

The main reason people aren’t calling for more monetary stimulus is that they think that monetary policy is already as loose as it can get (“Pushing on a string” etc.) and QE is just giving money to the banks. Why is this still so strong in the UK?

I think that the key reason is that we never REALLY had a monetarist counter-revolution like the US. Even at the peak of British monetarism in the early 1980s, right-wing people tended to attribute inflation to trade unions and left-wing people tended to attribute it to social conflict & oil prices. Monetarists weren’t even an overwhelming majority in the government that made the biggest deal about monetary targets (the Conservative government of 1979-1997).

The UK has a much more centralised academic community than the US and the key universities in terms of public opinion (Oxford and Cambridge) never endorsed monetarism at all. As late as the early 1990s, a majority of British economists supported an incomes policy as the only means of having low unemployment and low inflation.

While New Keynesianism was KINDA more influential in the 1990s (as it became possible for British economists to get away from the pitiful embarassment that real Keynesianism had become in the 1970s and 1980s while still keeping the ‘Keynesian’ label) the liquidity trap et al never died. The New Keynesian settlement in the UK seems to have been that the central bank controls inflation, while the government controls growth.

(In 1997-2008, this suited the government just fine: inflation wasn’t any lower than under the Conservatives’ inflation targeting of 1993-1997, but growth was much steadier than 1979-1997 and this could be attributed to Gordon Brown’s brilliance. As Milton Friedman noted, the effectiveness of an economic authority- in its eyes- depends on how well the economy is doing; the Fed becomes all powerful during golden periods and powerless after it’s made a mess of things!)

Most major British politicians have gone through the Oxford PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics) programme. I don’t know what the precise content of Oxford’s economics programme has been over the last thirty years, but it’s clearly not prepared any of them well for government.

So the combination of an ineffective economics programme at the key university for producing political suits and a political-economic orthodoxy that is totally incoherent is the key explanation for why no-one (who matters) in the UK is even talking about the solution.

29. January 2012 at 08:23

On Switzerland, here’s a piece from 2003 that comforts me by knowing that the UK is not the only place with an incoherent economic orthodoxy-

https://infocus.credit-suisse.com/app/article/index.cfm?fuseaction=OpenArticle&aoid=30668&lang=EN

“Switzerland has now one of the lowest short-term interest rates in the OECD world, complemented by a very low level of inflation. This mixture makes an effective monetary policy impossible”

“However, the most potent weapon to fight off deflation is an active exchange rate policy, especially for a country the size of Switzerland. By direct intervention, the Swiss central bank has to lower the external value of the Swiss Franc. Apart from the detrimental impact on the terms of trade, as export prices will decline and import price will increase, exports would increase. The liquidity trap would have been overcome.”

Yeah.

29. January 2012 at 08:27

No Scott, the real question is, What’s wrong with Germany? The actual champions of austerity, as you say fiscal deficit 1% of GDP, state sector also around social democratic 50-ish % of GDP, highly regulated economy, currency tied to the un-expansionary ECB, and doing … pretty well in comparison.

Of course they’re still being blamed for all and everything happening somewhere else in Europe… [/snark off]

29. January 2012 at 08:29

Firstly:

‘First a small point. Why is it so hard to find NGDP data for Britain?’

Any data is impossible to find for Britain. The ONS are awful. It’s bloody annoying.

I don’t think net deficits are a great way to look at fiscal stimulus, considering the main reason for the deficit is a drop off in tax revenues:

http://extranea.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/uk-debt-continues-to-grow1.gif

The deficit isn’t shrinking that fast because the departmental cuts are causing unemployment which cuts tax revenues and boosts welfare expenditure. However, the departmental cuts are still high.

29. January 2012 at 08:40

>>I don’t think net deficits are a great way to look at fiscal stimulus>>

Agreed. A common claim is that austerity reduces growth which reduces government revenue which increases deficits. To counter this with the claim that there are large deficits, therefore there is large stimulus seems very odd.

29. January 2012 at 08:57

UnlearningEcon and Foosion,

Whatever the merits of such arguments (and the empirical link between government fiscal stance and growth has been historically VERY weak in the UK) they cannot be coherently used in the UK context, since the deficits of 2008-2010 were also due to a fall in revenue and they are supposed (by those arguing that austerity is our current problem) to have caused the growth of 2010.

29. January 2012 at 09:17

W. Peden, Thanks for that info on the UK. I love the Swiss quotation: monetary policy is ineffective but currency devaluation works. (rolls eyes)

mbk, Good point.

UnlearningEcon, Yes, but the other European countries also experienced severe recessions and weak recoveries (except perhaps Germany and Sweden). Yet the UK deficit is much bigger than almost all the other European countries (except Greece.)

I recall liberals praising the Brown government for it’s massive fiscal stimulus. Why didn’t that promote a robust recovery, making further stimulus unneeded? Is it possible that fiscal stimulus doesn’t work when the central bank won’t allow fast NGDP growth, but will allow the pound to appreciate against the euro? (as it has recently)

foosion. See my previous answer. No matter how you measure the deficit, it’s been quite large compared to other countries (since 2008.)

W. Peden, Good point. We are supposed to accept on faith that fiscal policy in Britain is tight, even though I don’t see any objective metrics by which it’s tighter than other European countries. Indeed even Greece would be much tighter if you wanted to use some sort of “cyclically adjusted deficit,” as the Greek recession is far worse.

29. January 2012 at 09:19

W. Peden,

The argument is that the size of the deficit is not, in itself, the measure of whether or not there is stimulus or to what degree there is stimulus.

To say that one deficit was stimulative does not answer the argument. No one is saying that deficits cannot be stimulative or cannot coincide with stimulus.

29. January 2012 at 09:22

It seems that the anti-austerity argument (budget cuts in response to deficits undermine the economy leading to larger deficits) is a great argument for not running deficits to start with. I think the burden of proof is on the pro-stimulus camp to show that fiscal deficits are in any way stimulative in the first place. If deficits were stimulative, Japan and Greece would be thriving right now.

29. January 2012 at 09:24

>>Is it possible that fiscal stimulus doesn’t work when the central bank won’t allow fast NGDP growth>>

Scott, you’ve no doubt covered this, but who is arguing that a central bank can’t counteract fiscal stimulus?

29. January 2012 at 09:25

Scott Sumner,

Here’s an argument against what you’re saying that does have some meat on it: you criticise Keynesians for answering the question “How much fiscal policy is ‘loose’ fiscal policy?” with “As much as is needed (to get unemployment/real GDP back to the desired level)”.

However, you respond to “How much monetary policy is ‘loose?” with “As much as is needed (to get NGDP to the desired level)”. What’s the difference?

(I’m enough of an old (British) monetarist to say that UK asset prices (as indicated by a stagnant stock market) and a cyclically-adjusted look at broad money (http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/fm4/2011/nov/CHART1.GIF) suggest UK monetary policy is still too tight for a robust recovery, but you seem to forego all indicators other than the target variable, which is just what Keynesians tend to do, hence my question.)

29. January 2012 at 09:33

John, you’ve moved from spending cuts in your first sentence to deficits in your second. Also, there are other factors that affect economic performance than the size of a deficit.

http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2012/01/cochrane-just-dont-call-it-stimulus.html

29. January 2012 at 09:35

Foosion,

But if the supposedly stimulative deficit was caused by EXACTLY THE SAME MECHANISM as the supposedly unstimulative deficit (a decline in revenues) then there is a big problem of consistency.

Of course, you could say that (1) the UK’s recovery in 2010 was primarily due to monetary stimulus and that fiscal policy was a sideshow & that (2) the UK’s most recent NGDP slowdown was due to a number of factors and fiscal policy is one. However, then you’d agree with me and you would be right. 😉

29. January 2012 at 09:36

“Also, there are other factors that affect economic performance than the size of a deficit.”

Blasphemy! That would suggest that most of the UK’s economic debates over the past two years have been totally incoherent and wrong-headed.

29. January 2012 at 09:36

Another great posting, but “monetary stimulus is costless” raises a question. Is that net costless or costless for all parties? Surely big creditors and tin-foil-hat-wearing mattress stuffers think there is a cost to them. I would think the old money folks in England are among the former.

29. January 2012 at 09:41

@Scott:

First I want to agree about the difficulty of finding NGDP data in general. If you type NGDP in Google, it responds with “Did you mean GDP?”

But otherwise, I have a problem with your statement that a monetary stimulus would be costless. It’s not costless. It redistributes income from creditors to borrowers. That seems like a cost to me. Having an NGDP path targeting policy would be costless because we would all anticipate such “monetary stimulus” but a surprise bump in NGDP will mean some unexpected inflation which is a cost. (Even if the benefits outweigh the costs)

29. January 2012 at 09:46

@Scott

I should have paused before hitting submit on my awesome comment. I don’t see why monetary policy is the only place where we see the Chuck Norris effect. You keep saying that if Bernanke just screamed at the top of his lungs that he was going to print money and drop it out of helicopters the money supply would instantly expand without him having to do actual printing or dropping money from helicopters. Why can’t the same be true of fiscal policy? Monetary policy is held constant (as in sticking to the same interest rate) and the government screams that they are going to adopt an austere posture. So the money supply shrinks as everyone expects it to.

29. January 2012 at 09:46

PrometheeFeu,

I think that in that context “costless” means “costless for the state”.

29. January 2012 at 09:50

Scott, you’re right about NGDP being the same for the 3rd quarter — YoY growth was 3.0% although the QoQ SAAR was 4.2%. I can’t seem to find NGDP data for 4Q11; presumably it’s not available yet. Also, re your point about tax increases and inflation — the UK actually produces a CPI ex tax series which shows inflation as measured by CPI being significantly higher because of tax issues (I can’t remember the exact numbers off the top of my head, but probably ~2pp). I’m not sure how they calculate it though.

29. January 2012 at 10:32

As a Brit, I think you need to look more than the raw data with regards to fiscal tightening. The phenomenon is psychological and expectations based, there is a huge amount of rhetoric going around about imminent major fiscal tightening, a major requirement for us to tighten our belts and massive unsustainable debt. This is of course causing business and consumer confidence to plummet as we have very grim expectations of the future, which is causing demand to drop.

29. January 2012 at 10:33

Scott, I think it is enough to be an good old traditional monetarist here. UK’s broad money supply (M4) continues to contract. Furthermore, the even though the Bank of England talked about NGDP targeting it has been NGDP GROWTH rather than the level.

Maybe it would actually help if BoE announced an old-fashioned Friedmanite money supply growth rule. Obviously a NGDP level target would be best, but for now it is pretty clear that BoE needs to spur money supply growth.

29. January 2012 at 10:36

“While New Keynesianism was KINDA more influential in the 1990s (as it became possible for British economists to get away from the pitiful embarassment that real Keynesianism had become in the 1970s and 1980s while still keeping the ‘Keynesian’ label) the liquidity trap et al never died. The New Keynesian settlement in the UK seems to have been that the central bank controls inflation, while the government controls growth.”

I’m a postgraduate student at Warwick, my macro course content doesn’t say that the central bank only controls inflation, in fact last term most of the notes were on how monetary policy can have persistent effects on output. And these aren’t suddenly revised notes, if I look at the past exam papers from say 2004 or older editions of textbooks it’s still largely the same.

29. January 2012 at 10:44

W. Peden:

“Here’s an argument against what you’re saying that does have some meat on it: you criticise Keynesians for answering the question “How much fiscal policy is ‘loose’ fiscal policy?” with “As much as is needed (to get unemployment/real GDP back to the desired level)”.”

“However, you respond to “How much monetary policy is ‘loose?” with “As much as is needed (to get NGDP to the desired level)”. What’s the difference?”

Rare time when I agree with a Keynesian.

The “correct” answer to your question is that the Fed’s in charge instead of the Treasury, so all the economics get reversed. Incorrect and destructive ideas become correct and constructive ideas because it depends on who puts the same ideas into action. Instead of elected politicians controlling the economy’s aggregate spending, there are technocrats controlling the economy’s aggregate spending.

It’s bad when the Treasury owns GM stock to boost NGDP, but it’s good when the Fed owns GM stock to boost NGDP.

It’s bad when the Treasury boosts NGDP, but it’s good when the Fed boosts NGDP.

It’s bad when Keynesians do X. It’s good when Monetarists do X.

29. January 2012 at 10:48

Major_Freedom, it’s clearly bad for politicians to have control over the money supply because of an obvious and MASSIVE conflict of interest. The people who set government finance and expenditures shouldn’t be allowed to decide the interest rate they borrow their finances at or have the ability monetize their own borrowing at will, because this will clearly be abused constantly and create huge uncertainty.

29. January 2012 at 10:49

Scott,

I live in Britain, and I don’t post about my own country because the data is so bloody hard to find! The best thing you can do is actually call up the ONS. I often have to get hard-to-find data for my day job, and they have always been very helpful directing me towards what I need. Which is good, because the website is a total disaster.

It’s also worth noting that the ONS has been subject to a lot of criticism recently, and the BoE had a go at them a few months ago for not having data ready in time.

http://www.straightstatistics.org/article/ons-keeps-bank-england-waiting

29. January 2012 at 11:00

Ok a few things,

1) Nominal GDP and GDP deflators:

http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/data_gdp_fig.htm

This suggests that NGDP is around 10% below 5% trend line from 2007.

2)Scott, not sure where you got your figures for the UK’s deficit from.

But in the year to December 2011, net public debt (excluding the bank bailouts), rose from 59.4% to 64.2% of GDP.

In the most recent 12 months public debt has risen by 4.8% of GDP.

See the most recent public finance bulletin:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_253584.pdf

It is politically convenient for the Coalition for there to be “no money left”, particularly when negotiating public unions over pensions, pay and job losses.

3)As you and others have mentioned, much of the recent high inflation was because of tax changes, on page 10 of the most recent consumer price indices bulletin from the ONS reports that the consumer price index (CPI) with taxes held constant (CPI-CT) peaked at 3.5 in September 2011, and spent almost all of 2010 below 2%. See:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_250279.pdf

A large portion of recent high inflation has been due to tax increases. Has contractionary fiscal policy “caused” higher inflation?

Fortunately the tax rises will fall out of the inflation figures next month, headline CPI is likely to fall very quickly.

4)In real terms government spending has not been cut.

See:

http://www.ukpublicspending.co.uk/spending_chart_1985_2015UKk_11s1li111mcn_F0t_Total_Spending_Chart

There has been a reallocation from departmental spending (spending on Education, Defence, infrastructure, and local government) to spending on old age welfare.

The UK has no meaningful social security trust fund.

So our PAYG state pensions spending is entirely financed out of the current budget.

The percent of GDP spent on pensions has apparently risen from 4.59% of GDP in 2007 to 5.74% of GDP in 2012.

There have been similar increases in state health care spending.

To paraphrase Samuelson, the UK’s social security system is a Ponzi scheme that eats our children.

5)There have been other real supply shocks to the economy, in GVA terms North Sea Oil production has fallen by 26.3% between 2008 and 2011 Q3:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/naa2/second-estimate-of-gdp/q3-2011/sbd-second-estimate-of-gdp-q3-2011.pdf

Also major disruptions in the finance industry (down 3.9% since 2009) and construction (down 6.2%) in GVA terms (Table B1 in the above link).

6) Monetary policy may have been suboptimal.

What do you think happened to inflation expectations after Lehman failed?

The Bank of England provides the answer:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/yieldcurve/ukinf05(month_daily).xls

Plot the implied 2.75 year inflation breakevens from 2005-2011 from the spot curve.

Inflation breakevens fell from 2.85% on 1st September 2008 to -2.77% on 2nd December 2008. But the Bank of England did not lower short term rates to 0.5% and start quantitative easing until March 2009, six months after Lehman.

2.75 year inflation breakevens only rose above 2.5% after the 14th of January 2010, 14 months after Lehman.

In 2008, the Labour government of Gordon Brown pursued expansionary fiscal policy.

Why wasn’t the Bank of England more aggressive in cutting rates and pursuing QE?

Did fiscal policy fail? Or was monetary policy too tardy?

For bonus points, who should have been fired, Mr King, Mr Brown, or both?

29. January 2012 at 11:06

Brito,

I suppose I should have worn my Oxbridge centrism on my shirt and said “Oxbridge economists”. I know for a fact that, as early as the 1980s, Keynes was being written out of history in Bristol as having nothing to do with modern economics. So regional universities certainly do deviate, but all three of our major party leaders are Oxbridge men.

Lars Christensen,

Even if one could avoid the effects of an M4 target on velocity (and I would strongly advise looking at adjusted M4 rather than simple M4) the UK has such an open economy that the relationship of broad money to income is unusually poor. Having an M4 target for Britain would be a lot like having an M4 target for New York-

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=lp8fpcH-AZkC&pg=PA29&dq=%22the+world+is+monetarist%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=TZglT5jsAoXS0QXy_bHOCg&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22the%20world%20is%20monetarist%22&f=false

29. January 2012 at 11:16

“I suppose if you are a Keynesian you’d say that the housing/banking problems in Britain were worse, and hence you need more fiscal stimulus than Germany or Sweden”.

The smartest Keynesian of them all, Wynne Godley, once wrote:

“The budget balance is equal to the difference between the government’s receipts and outlays, but it is also equal, by definition, to the sum of private net saving (personal and corporate combined) plus the balance of payments deficit.

If the private sector decides to save more, the government has no choice but to allow its budget deficit to rise unless it is prepared to sacrifice full employment; the same thing applies if uncorrected trends in foreign trade cause the balance of payments deficit to increase.”

Britain’s 4% BOP deficit is a demand leakage, Germany’s 5% BOP surplus is a demand injection. So Britain’s 8.8% budget deficit is the equivalent of a closed system (or balanced trade) 4.4% deficit; Germany’s 1.0% budget deficit likewise is equivalent to a closed system’s 6% deficit.

29. January 2012 at 11:32

W Peden, I agree – my point was just that it is pretty clear that BoE really hasn’t done anything to expand the money supply.

29. January 2012 at 11:35

Beowulf,

I doubt that any smart Keynesian would write that, since “If the private sector decides to save more, the government has no choice but to allow its budget deficit to rise” mixes up quantity demanded (re:the government) with the desired quantity (re: the private sector) and no smart Keynesian would do such a thing.

Not to mention it talks about private sector saving in terms of saving income, whereas all smart Keynesians know that there is much more to the world than income and expenditure & that people save wealth rather than just income. So a monetary policy that boosted asset prices could induce the private sector to save less of its income even if the government was tightening its budget and the balance of trade was constant and even if the private sector want to boost their savings.

So given that Wynne Godley was a very smart Keynesian, I would want to see a citation before I believed he would say such a thing.

29. January 2012 at 11:41

Lars Christensen,

Yes. The post-1992 recovery should be the model: the government reduced its deficit while boosting the money supply to keep demand from falling. The result was the UK’s version of the Great Moderation. During the early years of that recovery (1993 and 1994) M4 growth was more than twice what it’s* been since 2009.

Broad money velocity is relatively high during this stage of a cycle, with a 2-1 ratio of M4 to NGDP growth being the norm during normal times and a near 1-1 ratio at the present time. So even a quite modest boost to adjusted M4 would kickstart a solid recovery in the UK, in terms of NGDP growth rates (though not levels).

* If you adjust for the distortions in the figures introduced by the financial crisis by excluding non-bank financial intermediaries.

29. January 2012 at 11:43

PS: Here are some historic M4 figures. As you can see, OFCs began to distort the figures during the UK housing bubble, but back when M4 more or less matched adjusted M4 it was a good guide to NGDP if you took the monetary cycle into account-

http://timetric.com/index/m4-annual-pec-change-sa-monthly-uk-ons/

29. January 2012 at 11:44

(Slightly less than 2 to 1, but I’m of the generation that didn’t really do much in the way of fractions at school!)

29. January 2012 at 11:45

If nothing else, conventional models provide for different multipliers for different spending programs. Not all deficits have the same effects. Looking only at whether there is a deficit or the size of a deficit is not particularly useful.

29. January 2012 at 11:49

Brito:

“Major_Freedom, it’s clearly bad for politicians to have control over the money supply because of an obvious and MASSIVE conflict of interest. The people who set government finance and expenditures shouldn’t be allowed to decide the interest rate they borrow their finances at or have the ability monetize their own borrowing at will, because this will clearly be abused constantly and create huge uncertainty.”

The Fed has the exact same “MASSIVE conflict of interest.” The people in control of the Fed would determine what the Fed spends, what the Fed purchases, what interest rates the Fed would borrow at, and they would also have the ability to monetize their own borrowing at will.

The people in control of the Fed constantly abuse the ability to print money (witness the fact that the NY Fed secretly transferred over $40 billion from 2003-2008 to finance the Iraq war). The people in control of the Fed also create huge uncertainty by constantly changing their “tools”, and constantly fostering the boom and bust cycle on the basis of artificially low interest rates and facilitating commercial credit expansion.

You aren’t getting rid of the conflicts of interest my giving the power to print money from one group to another. The only way that these conflicts of interest can be eliminated is by eliminating the power to print money.

The human temptation to abuse this power is just too great.

29. January 2012 at 11:52

beowulf:

You quote Godley as writing:

“If the private sector decides to save more, the government has no choice but to allow its budget deficit to rise unless it is prepared to sacrifice full employment;”

This only follows if one defines “private sector savings” as “government debt.”

But if one defines saving as “abstaining from consumption and investing instead, then should the private sector decide to “save” more, then people can save more and it doesn’t need an external entity to print and spend money.

29. January 2012 at 12:09

Fact is you can’t simply look at a budget deficit and know for a fact that fiscal policy was too loose.

What Greece has taught uf is that austerity can actually increase deficits by weakening demand and tax revenues.

“We are supposed to accept on faith that fiscal policy in Britain is tight, even though I don’t see any objective metrics by which it’s tighter than other European countries.”

Well most of you did accept it on faith-faith in David Cameron when he was elected.

andrewsullivan.thedailybeast.com/2011/…/why-britain-is-winning.ht… Thsi link shows you thought Britian was winning just in December, “that Britain’s actions will prove wise in the end.”

Now you are pretending that Cameron isn’t a fiscal hawk.

29. January 2012 at 12:14

Britain has too many human blobs and civil servants in the wagon… they have to get out and push.

Once real taxpayers on the fiscal side or the BOE reach said opinion – you can understand any and all policy decisions.

Monetary policy and government itself exists FIRST FOR the people who have money and own everything, if you pretend otherwise, or wish otherwise, you will always have the wrong predictive analysis.

29. January 2012 at 12:26

Mike Sax,

I don’t think that anyone is saying that fiscal policy is too loose. Most of us are saying that monetary policy in the UK is too tight.

29. January 2012 at 12:27

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/gdp-at-current-prices-imf-data.html

29. January 2012 at 12:31

Anonymous,

Re: Mervyn King and Gordon Brown, the answer is “both”. King and the MPC for their monetary policy performance; Gordon Brown for the recapitalisation madness in 2008.

Unfortunately, as with Bernanke I suspect that the alternative to King would be even worse.

29. January 2012 at 12:39

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/naa2/quarterly-national-accounts/q3-2011/index.html

29. January 2012 at 13:13

Central banks don’t automatically turn into George Soros or Warren Buffett at the zero bound. They aren’t set up to take market risk. They are set up to fiddle with the interbank rate, which is risk free. When the rate approaches zero, they lose credibility.

29. January 2012 at 13:13

W. Peden, paragraph 15 and you’re welcome.

“Why Gordon’s Golden Rule is now history

Eminent economist Wynne Godley argues that only ‘unacceptable’ budget deficits can save the UK economy”

The Observer, Saturday 27 August 2005

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2005/aug/28/politics.comment

29. January 2012 at 13:20

Nice post, Scott. I’m not sure about “errors of omission” though. Their (in)actions are considered, deliberate, and reasonably defensible under their mandate of targeting CPI inflation. Inflation is obviously the wrong target, but that is the government’s fault, HM Treasury sets the mandate every March.

In the first half of 2011 the BOE forecasts for CPI inflation (looking two years out) said that policy was too loose, and three of nine committee members were voting for rate rises all the way up to May, two of nine doing likewise up to July.

Towards the second half of the year, the forecasts were saying “too tight”, and they QEased accordingly. They seem to take a “hot potato” approach to QE, that asset purchases affect NGDP in real time, not merely policy announcements moving expectations.

Market inflation expectations have been a stronger signal to ease than the BOE internal forecasts, so if they started listening to Svensson they could probably do a better job even under an inflation target.

On 11Q4 GDP: the quarterly deflator growth was 0.3% in Q2, 0.5% in Q3, so an RGDP fall of 0.2% is quite scary, it hints at to a desperately low NGDP growth rate. It could get revised up, is the best we can hope for. The second estimate of GDP (February) has current price data, the national accounts (March) have proven more reliable though.

29. January 2012 at 13:21

John, Very good point. The Brown government that Krugman seemed to like so much ran deficits during the good times. Thus there was little room to expand deficits during the bad times.

foosion, Good point, I worded that poorly. I should have said “Is it possible the massive fiscal stimulus did no good because the BOE didn’t allow faster NGDP growth?”

W. Peden, You said;

“However, you respond to “How much monetary policy is ‘loose?” with “As much as is needed (to get NGDP to the desired level)”. What’s the difference?”

Good question, which I have addressed at times. Briefly, monetary and fiscal policy can’t be directly compared. One is like shoveling fuel onto the fire, and one is like turning the steering wheel. It’s costly to add fuel to the fire, so effectiveness is really important. Any given setting of a steering wheel is equally costly, so that has no bearing on monetary policy decisions.

anonymous, That site doesn’t have Q4 data.

My data was from the Economist, and is not inconsistent with your data.

Lots of good points. The fall in output from the North Sea and the City could reduce output quite a bit, without costing many jobs. But isn’t unemployment also rising?

Brown deserved to be fired, he was a disaster. I can’t say about King, because the problem may be his 2% inflation mandate. When inflation’s running 5% it’s tough to do a lot of QE. But that’s probably exactly what Britain needed.

D. Gibson and Prometheefeu, I meant it’s not costly to the government. In the rest of the economy there are winners and losers, but you don’t do it (and don’t do fiscal stimulus) unless you think the economy is better off with faster NGDP growth.

Prometheefeu, I don’t follow your second question. I agree that fiscal policy can affect expectations. I just don’t think it has much effect in practice. (Maybe a little.)

Federico. The UK government must have NGDP data somewhere, they’re just not releasing it to the public (I guess.) You’d think the NGDP data would come out first, as it’s much easier to estimate.

The gap in the two GDP figures 1.1% is probably the impact of the VAT on the GDP deflator (don’t know about the CPI.)

Brito, But we have exactly the same talk over here, and no recession is expected. So I’m confused. Not saying you are wrong, just that it doesn’t seem like a complete explanation–where is monetary policy in all this? That was my main point.

Lars, I suppose you are right about M4 giving the right signal right now. But I don’t find those aggregates to be very reliable, whereas NGDP is quite reliable. BTW, contrary to what many monetarists assume, it is not easier to control M4 than NGDP.

Richard, I hope the public pressure on them works–without data it’s hard to evaluate what’s going on.

beowolf, I don’t agree on the need for deficits. If monetary policy is expansionary there is no need for deficit spending, even if the public tries to save more.

Mike, I have no opinion on Cameron, and never did. Maybe he is a hawk. But I don’t see evidence of austerity, unless I’m missing something. I will concede that the deficit is smaller than in 2010, it’s just that the scale of reduction is typical after you’ve been in recession for three years, and nothing that should trigger a second recession with sound monetary policy. I think people are missing the point of this post, it’s not about fiscal policy (which I admit to not being an expert on) but about what seems to me to be an obvious need for more monetary stimulus. What’s the BOE doing?

Thanks Bill, but that doesn’t have the Q4 data that I’m looking for?

29. January 2012 at 13:26

“But if one defines saving as “abstaining from consumption and investing instead, then should the private sector decide to “save” more, then people can save more and it doesn’t need an external entity to print and spend money.”

MF, there is a difference between savings and private net savings.

Morgan, the MMT catfight continues. :o)

http://pragcap.com/monetary-realism

29. January 2012 at 13:28

Max, I agree that central banks have been addicted to interest rate targeting for decades. And I’ve been arguing that’s a huge mistake for decades. Now it looks like I was right. Time for a new target?

Britmouse. As usual, you have some excellent points.

The thing people don’t understand is that if they are really serious about inflation targeting, then a recession is good news, as it will help Cameron achieve his inflation objective. Of course I don’t believe a recession is good news, precisely because I don’t favor inflation targeting.

Do you know why they haven’t released the NGDP data for Q4? You can’t compute RGDP without NGDP.

29. January 2012 at 13:34

I don’t agree on the need for deficits. If monetary policy is expansionary there is no need for deficit spending, even if the public tries to save more.

Scott,

I wasn’t trying to convert you to the dark side. I was simply suggesting that balance of payments are a plausible alternative to “housing/banking problems” as to why Keynesians would think the UK needs to run a bigger budget deficit than Germany.

29. January 2012 at 13:36

“Brito, But we have exactly the same talk over here, and no recession is expected.”

I think Americans are naturally more optimistic than brits, who are generally more cynical and pessimistic.

“where is monetary policy in all this? That was my main point.”

Inflation has been consistently 2 percentage points or so above its target, nobody is expecting any more loosening of monetary policy.

29. January 2012 at 13:41

@ssumner:

My understanding of your argument regarding the ineffectiveness of fiscal policy is that monetary policy moves last. So let’s imagine that fiscal policy is becoming more austere and the central bank is just defending a particular interest rate. At this point, you would see a fall in NGDP right? Now normally of course, the central bank seeing austerity programs would loosen in order to hit its targets and that would counter the fiscal austerity.

Well what if instead of fiscal policy actually tightening, they just scream at the top of their lungs that they are adopting austerity programs, make a few symbolic cuts and then wait and see. Well, the central bankers are sophisticated enough to know the difference between table-thumping and real austerity, so they don’t adjust their policy stance and keep their interest rate target. The rest of the economy though sees “fiscal austerity.” So they start hoarding money and NGDP shrinks. Eventually of course, the central bank will see its mistake, but you might already have entered a recession by then.

29. January 2012 at 13:44

@ssmuner:

I’m not really saying that’s happening. I’m just saying that’s a story that doesn’t seem inconsistent with your model AND a fiscal austerity-caused recession. Though of course, you’d be free to blame the central bank’s mistake for the recession.

29. January 2012 at 13:45

Scott, “GDP at market prices” is the same as nominal GDP right?

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/gva/gross-domestic-product–preliminary-estimate/q4-2011/stb-q4-2011.html#tab-Key-Figures

29. January 2012 at 13:50

Scott,

I see. So, since the central bank can increase base money for as long as there are assets it doesn’t own (though curiously NOT the reverse if the central bank is doing LOLR) its performance can be judged by the supply of base money modified for its income velocity, which is NGDP?

And because fiscal policy is more constrained, we can’t regard the target variable as a measure of its tightness or looseness. Instead, we look at the constraints (how spending is financed) rather than the target variable?

29. January 2012 at 13:55

[…] takes a Market Monetarist like Scott Sumner to come out and speak against “Monetary Austerity”: Keynesians are focusing on the fiscal part […]

29. January 2012 at 14:13

beowulf:

“MF, there is a difference between savings and private net savings.”

Yes, but only you define “private net savings” to be government debt.

It’s not necessary for the entire private sector to hold more money. The demand for more money is always greater than the supply. Money has to scarce in this way for it to function as a money.

If everyone in the private sector wants to hold more cash, then what they are actually looking for is more purchasing power. In an unhampered market, a general increase in the demand for money holding will have the effect of falling prices. Once prices fall and cash holdings increase to satisfy the additional demand for money holding, then people will find there is no longer any need to hold more money. They got their increased purchasing power.

The accounting tautology that private holdings of dollars cannot increase on net without an additional quantity of money, does not contain any normative argument on what people should do with that knowledge.

You MMT guys say “private net savings cannot increase without inflation from the government” as if private net savings (defined in that way) SHOULD increase, or that the desire for individuals to hold more cash SHOULD be “accommodated” by money printers.

Private savings can remain flat and yet facilitate a practically infinite growth in the real economy, on the basis of falling prices (and costs!)

29. January 2012 at 14:20

@Brito, there really is no current price (nominal) GDP data for 2011 Q4 yet – it will come in February.

@Scott, they said they used a lot of “volume indicators” in the first estimate of GDP. You are right on the recession, but I fear the results; severe damage to profits could result in less competition in the markets, damage to the government could result in an electorate “turning left”. We could end up with price controls and the 1970’s again, though maybe I’m being melodramatic.

@W. Peden, Lars and others on M4: the Bank’s preferred M4 ex OFCs measure was not falling in 2011, and spiked up nicely after they restarted QE in October; could just be coincidence.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/fm4/2011/nov/index.htm

29. January 2012 at 14:20

ssumner:

“Briefly, monetary and fiscal policy can’t be directly compared. One is like shoveling fuel onto the fire, and one is like turning the steering wheel.”

Why is bringing about more aggregate spending by making purchases financed with inflation “adding fuel to the fire” for one agency, but bringing about more aggregate spending by making purchases financed with inflation is “turning the steering wheel” for the other agency?

What is the difference between the Treasury buying GM equity, and the Fed buying GM equity? Why is the Treasury adding fuel to the fire, but the Fed is at the steering wheel?

What if the Treasury started buying mortgage backed derivatives and other “assets/securities” from the primary dealers, and the Fed started buying military weapons from contractors and GM stock from investors? Would the Treasury be steering the wheel and would the Fed be adding fuel to the fire?

29. January 2012 at 14:35

Britmouse,

Adjusted M4 wasn’t falling, but its growth rate was slow (and nearly 0) in the first part of 2011. Velocity has increased, but not so much that a 1.5% annual rate of growth is compatible with 5% NGDP growth.

It’s hopelessly outdated, but the old Friedman rule-of-thumb with American M2 was that a change in broad money has an effect on output after about six months on average and inflation after about twelve months on average. So the current output slowdown is what you’d expect, given the slowdown in NGDP and broad money.

On that basis, one shouldn’t expect Q1 2012 to be as bad as some people think. However, it is certain that QE2 UK is not enough to give us the recovery in NGDP that we need.

29. January 2012 at 14:41

@Britmouse

Okay, but then what was that in the link I posted? It said it was GDP at market prices.

29. January 2012 at 14:43

Much of UK debt has been sold inflation linked so monetary loosening does have a cost to the state. UK cannot inflate away it’s debts because sterling is not the world currency.

US and China will eventually fall out over US debt and China tracking the dollar.

The old debtor/creditor argument.

UK (being a debtor) must pay down deficit (by shrinking state) and lower taxes/regulation on business to create jobs and growth.

Increase pension age to 70 and get 16 year old’s in work rather than state education is the way to grow. Best way to achieve growth is to increase the working population and decrease the state dependent population.

Large corporation tax cuts are required in the short term and changes to make state education more relevant to industry and commerce in the medium term.

But what to do about the ageing population??

Ditto massive spending on health??

29. January 2012 at 14:48

[…] post for a few days and don’t really know what I am trying to say. Still, now that Sumner has beaten me to the punch, I’ll post so that people can see recent movements in British NGDP, at least as of the third […]

29. January 2012 at 15:20

MF,

There are many things to like about Scott’s plan… one of them is that a level targeted 4% forces the government to actually WANT to drive down prices. Suddenly the bias choice is side with any and all forces that push prices down because it opens up room under the 4% cap.

29. January 2012 at 15:54

@W. Peden. Good points.

@Brito, it is real GDP; unless they qualify “GDP” with “current prices” it always means real GDP. “market prices” means inc VAT, “basic means ex VAT”.

@Morgan, the UK budget was adjusted in November based on a forecast of several years of low NGDP growth (3.5% in 2012, ye gods); the response was to push down on public sector pay and benefits… and redirect the savings to capital spending. They don’t give up on spending our money very easily!

29. January 2012 at 16:15

@Scott, link earlier doesn’t work and I can’t link to the page so I’ll take a screenshot:

http://gyazo.com/6da5501d7548fadc02e9396f5753abdf

@Britmouse

“@Brito, it is real GDP; unless they qualify “GDP” with “current prices” it always means real GDP. “market prices” means inc VAT, “basic means ex VAT”.

Are you sure? I realise the link didn’t work so I took a screenshot of the page since I can’t link to it for some reason:

http://gyazo.com/6da5501d7548fadc02e9396f5753abdf

Notice the figure for q4 is -0.2% which is different to the reported real figure of -0.8%. Also according to this:

http://www.cliffsnotes.com/study_guide/Nominal-GDP-Real-GDP-and-Price-Level.topicArticleId-9789,articleId-9734.html

“Nominal GDP is GDP evaluated at current market prices. ”

Why on earth would real GDP data be available before nominal data, despite nominal being easier to compute and required to compute real data?

29. January 2012 at 16:49

Morgan Warstler:

“There are many things to like about Scott’s plan… one of them is that a level targeted 4% forces the government to actually WANT to drive down prices. Suddenly the bias choice is side with any and all forces that push prices down because it opens up room under the 4% cap.”

I think you’re ignoring something crucial here. When prices fall, that does’t mean there is less aggregate spending, thus creating “room” for the government to spend more. If prices fall on the basis of higher productivity, in a given aggregate demand, then there is no “room” for more government spending that doesn’t come at the expense of private “C” and “I”.

NGDP targeting is a targeting of aggregate spending, not prices. The government has no incentive to lower prices and every incentive to raise them. It’s not their money and they don’t incur the costs. Even in a fixed NGDP world, the government can just take up a larger portion of aggregate spending by raising its “G” at the expense of private “C” and “I”.

Or maybe I completely missed your point…

29. January 2012 at 17:08

MF, as Britmouse notes, the effect is that we gut public employees.

There would be other effects as well:

1. greater fear of inflation. it isn’t a gold standard, but it is closer to a gold standard then we have had (less inflation historically).

2. ALL AROUND demands that gvt. make the productivity gains that the private sector makes…. got deflate to find room for private sector growth.

“Even in a fixed NGDP world, the government can just take up a larger portion of aggregate spending by raising its “G” at the expense of private “C” and “I”.”

I think this is a bit of a break-through on the getting to know you front.

My whole bet with Scott is about the new “haves” voting hegemony, being so Large, Wired and Powerful that when there is a DIRECT UNOBSCURED choice between gvt. getting to spend or the private sector getting to borrow cheap, the gvt. will eat it.

If you just think about NGDP targeting as an easily reached cap (4%), we can get down to the real day-to-day gvt. throat-slitting the main street private sector is capable of.

Suddenly ANYTHING that pushes up NGDP that isn’t small business private sector RDGP is evil and bad: raising entitlement, more student loans, raises for public employees – all of it will carry and actual PRICE TAG in GDP – we’ll not ask “how much does i cost?” well ask “how does this artificially raise our GDP?”

29. January 2012 at 17:54

Morgan Warstler:

“MF, as Britmouse notes, the effect is that we gut public employees.”

I don’t see how that follows. Why would the government have to cut its spending? As long as NGDP rises at 5% or whatever, the government can take up 10%, 20%, 30%, etc of total spending.

“There would be other effects as well”

“1. greater fear of inflation. it isn’t a gold standard, but it is closer to a gold standard then we have had (less inflation historically).”

Granted.

“2. ALL AROUND demands that gvt. make the productivity gains that the private sector makes…. got deflate to find room for private sector growth.”

This assumes the government has an incentive to do that, but granted.

“Even in a fixed NGDP world, the government can just take up a larger portion of aggregate spending by raising its “G” at the expense of private “C” and “I”.”

“I think this is a bit of a break-through on the getting to know you front.”

“My whole bet with Scott is about the new “haves” voting hegemony, being so Large, Wired and Powerful that when there is a DIRECT UNOBSCURED choice between gvt. getting to spend or the private sector getting to borrow cheap, the gvt. will eat it.”

How is that? This doesn’t stop the government from taxing and spending more.

“If you just think about NGDP targeting as an easily reached cap (4%), we can get down to the real day-to-day gvt. throat-slitting the main street private sector is capable of.”

Horrible metaphor, but yes, there is of course a larger constraint on reckless spending with NGDP targeting.

“Suddenly ANYTHING that pushes up NGDP that isn’t small business private sector RDGP is evil and bad”

Woah, how can RGDP “push up” NGDP? Increases in RGDP won’t result in higher NGDP unless there is more money and spending associated with it. But more money and spending is a function of the quantity of money, not the quantity of goods.

“raising entitlement, more student loans, raises for public employees – all of it will carry and actual PRICE TAG in GDP – we’ll not ask “how much does i cost?” well ask “how does this artificially raise our GDP?”

Good point.

If your standard is the current system, then NGDP does represent an improvement, but it is not a long term, constructive system in itself, because it has the same critical flaws as the current system.

29. January 2012 at 19:00

“I agree that central banks have been addicted to interest rate targeting for decades. And I’ve been arguing that’s a huge mistake for decades. Now it looks like I was right. Time for a new target?”

They aren’t targeting interest rates as far as I know. The interbank rate is the tool, not the target. Problem is, they are lost when they can’t lower the rate.

I have doubts about whether buying government bonds is a stimulus in any quantity. The bonds are negatively correlated with market risk – they pay off when monetary policy fails. So in a way, the central banks are betting on their own failure, which doesn’t seem a good tactic for inspiring private risk taking.

29. January 2012 at 20:07

“If your standard is the current system, then NGDP does represent an improvement, but it is not a long term, constructive system in itself, because it has the same critical flaws as the current system.”

This is exactly my position on Scott, he gets us closer to an Austrian model… all Austrians ought to play dirty and take the land grab.

“Woah, how can RGDP “push up” NGDP?”

RGDP + Inflation have to stay under the 4% cap.

The non-rent seeking part of the private sector will want that entire 4% to be RGDP, as such, deflationary forces will be CHEERED.

And finally, I think you have to admit we (the right) is getting better and better at getting taxes cut.

30. January 2012 at 01:27

Scott,

There’s like 70 comments here so forgive me if I haven’t read them all.

First of all NGDP data is easy to access for the EU. Just go to Eurostat.

Secondly,

Aargh. Isn’t this a bad way to be welcomed back to your community? The last thing I wanted to do was to be fired by my prick of a boss.

Third,

On the bright side I get UI. I get to sit at home and work on my dissertation with 60% pay but not spending 40% on gas and tolls. So it all works out, eh?

Fourth,

Thanks to global warming my heating bill is down 25% over previous years. It’s a contest between peak oil and climate change but on the whole I think I’m ahead.

If I think of moe points I’ll let you know.

30. January 2012 at 04:31

The ONS is hopeless. There is no NGDP released yet, only RGDP. Except … when it comes to showing the public sector deficit as a percentage of GDP at market prices (NGDP). Then you can calculate their first estimate. It’s under Financial Statistics Monthly – December 2011 here:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-226912

The the tab FS21.1D_4

It shows 1.3% annualised NGDP for 4Q 2011. Better than the 1% of a year ago, but down from the 2% peak in September.

30. January 2012 at 04:50

Scott,

As far as I’m aware, the UK nominal GDP data aren’t published until the second estimate of GDP is released (a month after the first).

Q4 should appear at this link in a month’s time (I think!)

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/datasets-and-tables/data-selector.html?cdid=YBHA&dataset=ukea&table-id=A1

30. January 2012 at 05:10

Morgan Warstler:

I said: “Woah, how can RGDP “push up” NGDP?”

You said: “RGDP + Inflation have to stay under the 4% cap.”

The units of RGDP are, of course, real goods and services. T-shirts, potatoes, and computers.

The units of inflation are in dollars.

How can one add incommensurable units?

30. January 2012 at 05:17

@James, the public sector finance stats use an NGDP figure which extrapolates from the growth rate in previous quarters, there is no Q4 outturn data in there.

30. January 2012 at 05:39

Beowolf, OK, but again, if that’s their reasoning, it’s pretty poor logic.

Brito, You said;

“nobody is expecting any more loosening of monetary policy.”

So they want a recession? Obviously not. Do people in Britain not understand that raising AD tends to raise inflation?

Prometheefeu, You said;

“Well, the central bankers are sophisticated enough to know the difference between table-thumping and real austerity, so they don’t adjust their policy stance and keep their interest rate target. The rest of the economy though sees “fiscal austerity.” So they start hoarding money and NGDP shrinks.”

But in that case they wouldn’t be “sophisticated” at all, they’d be simpletons.

Brito, It should be NGDP, but all the numbers in that table are RGDP. The plot thickens.

W. Peden, It’s even worse, it’s not clear the central bank has to increase its balance sheet at all, just set a more robust target.

Britmouse, God knows what “volume indicators” are. It sounds like they aren’t trying to measure RGDP at all, just estimate it from sort sort of correlated number, like trucking shipments, or something like that. There is no such thing as “volume” in industries like commercial construction, unless a skyscraper and petrol station both count as one unit.

Major Freedom, As I told you before, monetary policy is not buying GM stock. And increasing the monetary base is not necessarily expansionary, as we’ve seen in recent years.

Bikerscum, You said;

“Much of UK debt has been sold inflation linked so monetary loosening does have a cost to the state. UK cannot inflate away it’s debts because sterling is not the world currency.”

No, the burden of indexed bonds is not really affected by inflation.

No creditor/debtor problems with NGDP targeting.

Britmouse. Is RGDP growth the same at basic prices and at market prices? If not, why not? Is it a different weighting of categories?

Brito, the minus 0.2% and 0.8% are the same data point. One is reported at an annual rate, the other isn’t.

Max, You said;

“They aren’t targeting interest rates as far as I know. The interbank rate is the tool, not the target. Problem is, they are lost when they can’t lower the rate.”

I meant as a short run target, i.e. tool. If they were really serious about inflation they ought to target TIPS spreads (or the UK equivalent) not short term interest rates. But of course targeting inflation would be a big mistake.

Mark, OK, if it’s easy find the Q4 growth in UK NGDP.

James, Wow, 1.3% NGDP growth isn’t going to keep them out of recession. The BOE is behaving very bizarrely, and no one seems to notice. They ran 5% NGDP growth during the good times, why such low NGDP growth today?

Dan L. Aren’t people in the UK complaining? There’s no logical reason to publish RGDP numbers before NGDP.

30. January 2012 at 05:53

“Brito, You said;

“nobody is expecting any more loosening of monetary policy.”

So they want a recession? Obviously not. Do people in Britain not understand that raising AD tends to raise inflation?”

It’s generally regarded that more QE is the only way the BoE may be more loose than it is already, and QE seems to be a tool used by the BoE only when equity prices are plummeting or as some sort of bank recapitalization method, but equity prices aren’t plummeting and banks are sufficiently well capitalised for the moment, so nobody expects there to be QE as such a move is completely unprecedented when inflation is so high.

30. January 2012 at 05:53

“Brito, the minus 0.2% and 0.8% are the same data point. One is reported at an annual rate, the other isn’t.”

Oops, my bad.

30. January 2012 at 06:01

Scott:

Would Keynesianse be able to argue that the budget deficit is due to the austerity measures, not despite them?

If you look at Krugmans last post on the UK, you can see that the economy has recovered much less in terms of GDP even compared to the great depression:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/28/the-worse-than-club/

If one had the same gdp recovery and gdp at 108 in stead of 101, you would have 7 extra pp of GDP. With tax receipt ~40-50%, that’s 5-6% deficit in stead of 8.8%, and comparable to France.

Is there anyway to look at the data to exclude that this is what is going on? Don’t get me wrong, i agree with you that monetary policy should be first, but won’t Keynesians be able to use this as an example that austerity is self-defeating?

30. January 2012 at 06:14

@Scott “It sounds like they aren’t trying to measure RGDP at all, just estimate it from sort sort of correlated number, like trucking shipments”

Yes, I think that is exactly right for the first estimate of GDP, hence why it is subject to significant revisions.

“Is RGDP growth the same at basic prices and at market prices”

I hadn’t thought about that before, but yes, the ONS numbers do differ very slightly for some quarters, and no, I don’t understand why.

30. January 2012 at 06:14

Brito, So people in the UK don’t think monetary policy impacts AD?

eivindho, Yes, I’ve heard that “Laffer curve ” argument recently. But consider the recent rise in the VAT (from 15% to 20%, I believe.) Obviously that will bring in more revenue. I think it’s also extremely likely that it will reduce the deficit, but it’s conceivable it would not.

As I said, I do think the higher VAT may be a part of the problem, so I’m not completely ruling out fiscal policy. But the obvious solution is to then focus on monetary stimulus. That’s the real purpose of my post–why aren’t the British focusing like a laser on monetary policy?

30. January 2012 at 06:39

“So people in the UK don’t think monetary policy impacts AD?”

AD = GDP = Y = C + G + I + Trade Stuff.

I don’t see inflation in there, yet we know that monetary policy is all about inflation.

30. January 2012 at 06:46

Why no mention of QE in the UK? As far as I can see in this post and comments there is no mention of QE3. The Bank of England is doing more than any other central bank in the world at the moment by buying the entire net debt issuance of the UK Treasury’s Debt Management Office.

It does this in an admittedly roundabout way. The DMO issues “new” gilts to the market, the market shuffles its gilt holdings around a bit, and sells back similar dated issues to the BoE. In this way the BoE finances the entire excess Treasury expenditure over receipts.

However, remember it’s QE3 we are on. If it is easing our arch-easer is Adam Posen, MPC member, and (apparently) a leading American monetary economist. Many of us are wary of him as he also appears to support fiscal stimulus and a general increase in government intervention.

30. January 2012 at 06:46

The 1.3% implied NGDP growth in 4Q is a QoQ, so c.5% annualised but decelerating from nearly 8% annualised in 3Q. However, following Britmouse’s link the data the ONS uses is just an extrapolation of earlier trends.

30. January 2012 at 06:57

I don’t understand what your point is…

I would argue BoE has been the most active central bank (possibly after swiss). They have a much harder problem to solve. Financial services are a huge part of the UK economy, so they have much bigger supply side problems than everyone else…

They totally ignored the 2% target (with the goverment blessing). I think the central bank already owns 25% of govermnet debt… They are planning to do a lot more (at least that’s what the market expect)…

The austerity was pretty modest and I doubt it made much difference either way. I think the entire thing is a wash.

30. January 2012 at 07:19

“Brito, So people in the UK don’t think monetary policy impacts AD?”

Average people in the UK don’t know much about central banking and couldn’t really care less about monetary policy, other than when interest rates are being adjusted in a way that could affect their own interest rates, but this isn’t the case here since we’re at the lower bound. But in as much as laymen are interested, QE would be seen as simply printing money and giving it to bankers, they don’t regard it as any sort of panacea.

30. January 2012 at 07:48

“I would argue BoE has been the most active central bank (possibly after swiss).”

Have they been Accarro? What have they done? Not saying your wrong that’s my impression as well but it sounds like you know more about it than me.

30. January 2012 at 08:10

Plosser on CNBC this morning: “Fed may need to raise interest rates in 2012 or 2013.” – justified by an improved labor market with unemployment falling to 8%.

Plosser-San, when do you leave the Fed?

30. January 2012 at 08:13

ssumner:

“Major Freedom, As I told you before, monetary policy is not buying GM stock.”

Yes, but you didn’t explain why. You just dismissed it. I asked what if the Fed had to choose between getting the NGDP target by buying GM stock, or not buy GM stock and miss the target. You didn’t respond. I can’t just go by your say so on this. Merely telling me “that’s not monetary policy” doesn’t cut it.

If monetary policy is the central bank printing money to buy assets owned in the market, then why shouldn’t GM stock be included?

If the response is along the lines of “I don’t prefer them to be buying GM stock”, or “It would be a bad idea for the Fed to start owning GM stock”, or “Most people in group X don’t view monetary policy that way”, then you wouldn’t be basing your response on a solid foundation, but rather your whims, or the whims of the majority of those in group X.

“And increasing the monetary base is not necessarily expansionary, as we’ve seen in recent years.”

Nobody argued increasing one component of the money supply like the monetary base is necessarily expansionary. The argument is the reverse. The argument is that the sustained increase in credit expansion which blew up the housing bubble necessarily required expansions in the monetary base, the absence of which would have made the bubble impossible to form.

It’s like the difference between saying “High speeds necessarily cause crash deaths” and “His crash death necessarily required him to be going at a high speed.” You can accept the latter without having to accept the former.

30. January 2012 at 08:28

>Yes, but you didn’t explain why. You just dismissed it. I asked what if the Fed had to choose between getting the NGDP target by buying GM stock, or not buy GM stock and miss the target. You didn’t respond. I can’t just go by your say so on this. Merely telling me “that’s not monetary policy” doesn’t cut it.

I was thinking about this topic this morning. Quantitative easing has an optics problem – the public perceives it as disproportionately benefiting Wall Street, but interest rates are already too low and we need much more monetary stimulus. It seems the Fed is (for some reason) concerned about the political feasibility of more stimulus, so what would be the most popular way to do this?

To accomplish that I think the Fed needs to find a way to put those extra dollars in the hands of as many people as possible. So how do you implement it? A lottery with a positive expected return? Cash deposit to accounts registered to valid SSNs? How about Payroll Stimulus (The Fed pays your payroll tax, employee and employer sides, so you just have a larger take-home paycheck)?

30. January 2012 at 08:46

Cthrom, the reason the futures market makes sense is the printed money goes into the hands of the bettors. The Fed isn’t buying any assets, it just puts money on the table, takes money off the table.

Personally, right away I’d like to see the Fed buy up foreclosed housing (selling for less than X of last sale) and auction it in $1 auctions… take action to drive shadow inventory out to sale.

Use the “stimulus” for force liquidation.

If they simply offered 75% of current foreclosed prices on every current foreclosure, and re-auctioned them at $1, we’d see all the current foreclosures liquidated.

They could even offer low-balls on short-sales to those underwater, and let the banks take them. Hell, you could even let the current owners BID in the auctions assuming the short sale didn’t ding their credit too badly.

30. January 2012 at 09:10

@Morgan,

Using the Fed to directly clear the housing shadow inventory is appealing, but what would be the behavioral effects? If the Fed announced such a policy, and it didn’t take effect immediately, then rational people would stop paying their mortgage in the hope of buying back their home (or a better one) at lower cost. So this would have to be a one-time, immediate action by the Fed. But how does the Fed get possession of the homes in the first place? The banks do not want to take write-downs on these non-performing loans. Does the Fed simply make them whole? I’m fine with that, but I’ll definitely be in line bidding on local foreclosures as rental properties.

30. January 2012 at 10:03

There are a zillion comments, so I hate to add another nutty one, but what *is* the “stance” of US fiscal policy? Line 27 of table 3.2 at http://www.bea.gov looks like this:

Year Net Government Saving (billions)

2005 -257

2006 -153

2007 -233

2008 -686

2009 -1296

2010 -1299

When economists talk about stimulus, they never seem to talk about this. Why isn’t this “fiscal stimulus?” I thought “automatic stabilizers” were fiscal stimulus, but it doesn’t seem economists in general think that these budget deficits are providing much help to the economy. I.e. apparently they’re too small.

I guess part of the argument is that since interest rates are so low, these deficits aren’t crowding out investment….

I guess more than anything I’ve been really surprised that the saltwater/freshwater argument is about “fiscal policy works/doesn’t work” instead of being about “fiscal policy not enough/too much” or even “fiscal policy worked/didn’t work.” The actual (first) argument seems utterly pointless while the other arguments could actually be interesting.

30. January 2012 at 10:28

Foosion:

Private borrowing expands at around 1% of GDP normally. When government borrowing expands at around 3% of GDP normally and is at 8% of GDP now, the fiscal accelerator is at the floor and you cannot seriously kid yourself that there is much difference then between 8% and 9%.

Second, there is no reason for austerity to transmit to NGDP unless the CB allows it to do so. *It might transmit to RGDP*.

But on that point, we need to confront one of the fictions of GDP. It is well understood that mere transfer payments do not contribute to GDP. Yes, those UI checks do not count! What’s more tricky is when transfer payments are concealed under the guise of government purchasing. I.e., if the government pays twice the usual rate for something, GDP ought not to reflect twice the output, rather there is the ‘normal value’ and a ‘transfer payment’ in that transaction.

When the government sets the price (e.g., fighter jets, bridges, etc) its very difficult to tease out what’s what.

This is also one of the reasons Greece is in such poor shape. The government employees a lot of people in do nothing jobs, and this work gets mistakenly marked down as output rather than a transfer payment. Greek GDP is much smaller than reported.

30. January 2012 at 10:43

>This is also one of the reasons Greece is in such poor shape. The government employees a lot of people in do nothing jobs, and this work gets mistakenly marked down as output rather than a transfer payment. Greek GDP is much smaller than reported.

The number one occupation in the United States is K-12 teaching. Education spending is at all time highs, measured output (test scores) has not increased in more than 30 years. Sounds to me like this is mostly day care now, so anything in excess of a typical day care professional’s salary is a transfer payment to union workers.

30. January 2012 at 10:56

Expectations of fiscal tightening ?

I still see a lot of “Ricardian equivalence” arguments about expectations of future fiscal tightening caused by present government spending reducing present consumption. I think they’re silly. A government with a sustainable budget balance before a recession will have a sustainable budget balance if and when the economy returns to full employment. Debt/GDP then tends towards deficit/dNGDP, IIRC. In other words, a bout of spending now may well pay for itself in the long run. Consumers need not worry about their taxes increasing.

On the other hand, a tightening of spending means job losses, at least for people working for the govt. or expecting to find a govt.-related job. More generally, people hear about “sustainable budget” blah blah blah and see the same old sh*t coming their way. Consumers’ future expected income depends more on their keeping their job than any change in marginal tax rates. Expected vs. actual saving debates aside, see where I am going ?

It all depends whether people think in Keynesian or Austrian terms :^)

Second, I would expect the UK economy to be tightly linked with the eurozone, especially through financial markets.