The rhinoceros theory of the Fed.

Arnold Kling made an interesting comment about the Federal Reserve:

I can think of at least three reasons why the Fed is not pursuing expansion with more determination. First, current policy is much closer to optimal for banks than it is for the country as a whole. This suggests a Fed controlled by banks. Second, the Fed may be intimidated by those who oppose faster expansion. Third, the Fed is just very slow to change direction. One story for the 1970s is that the Fed kept under-estimating the shifts in the Phillips Curve and the increases in the natural rate of unemployment. It kept following inflationary policies because it was slow to adapt to reality. Similarly, it appears now that the Fed is slow to adapt to downward shifts in aggregate demand. It is adjusting gradually while conditions are deteriorating rapidly. In the 1970s, the Fed took too long to tighten, and now it is taking too long to loosen.

I disagree with the first point (tight money hurts banks—check out their stock prices), and agree with the second. But it’s the third that intrigues me.

Suppose the Fed and ECB are big lumbering institutions, like the Catholic Church. They develop a set of myths that guide them. In the 1960s it was the myth that a bit higher inflation is actually a good thing, because of the Phillips Curve. So from 1965 to 1981 inflation and inflation expectations moved relentlessly higher. As early as 1968 Phelps and Friedman had shattered the idea of a stable Phillips Curve. By the 1970s it was clear that inflation wasn’t buying lower unemployment. But the Fed kept inflating. Monetarist theory was a fringe idea, and the Fed is very much an establishment institution. Only in 1981 (not 1979 as many wrongly believe) was there so much disgust with inflation, and such a widespread understanding of the natural rate hypothesis, that the Fed was able to reverse course and squeeze inflation out of the economy. And when they made that decision in mid-1981 it happened really fast. Monthly inflation rates quickly fell from 10% to 4%, and basically stayed low thereafter. But even now I’m amazed that it took 16 years for them to realize they were on the wrong track.

So the Fed’s like a charging rhino that finds it hard to re-evaluate its trajectory and change direction. How does that fit the recent history?

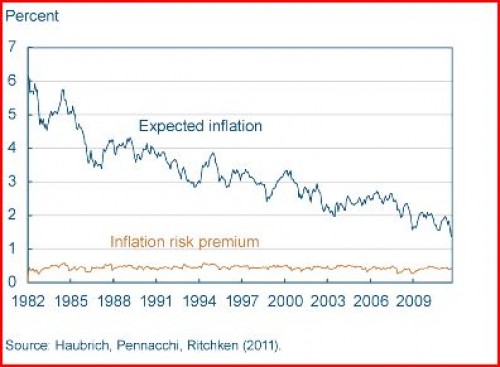

Although we think of the Great Moderation as having stable inflation, it’s not quite that simple. Inflation has fallen from 4% in the 1982-89 period to 1% in the last three years. And expected inflation has fallen even more sharply. Here’s some estimates from the Cleveland Fed:

I used to have a sort of Whig view of the history of the Fed. They did all sorts of really stupid things in the Great Depression and the Great Inflation, and then they finally found the right policy. This led to low and stable inflation. The last few years, and especially the last few days, have disabused me of that view. Here’s an interesting excerpt from The New Republic article I cited in the previous post:

There is no doubt that predictable price levels are a necessary aspect of monetary credibility. But for many on the right, low inflation is not a matter of good policy, but an ideological dogma: inflation must always be fought, regardless of the state of the economy, and regardless what the data tell us. As Dallas Federal Reserve President and CEO Richard Fisher described it last summer, he was “committed to keeping inflation low and maintaining the credibility gained so painstakingly by former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker. I will remain steadfast in my resolve to keeping inflation low and stable.”

If Fisher was really for “stable” inflation, he’d be horrified that inflation has dropped to only 1% over the past three years. But I have a feeling that Fisher is not horrified by this instability, this drop in inflation. Instead, he seems to exalt in the never-ending fight against inflation. The Volcker story is of course a myth. He reduced inflation to 4% in 1982, and then stopped. Why did he stop? Because unemployment rose to 10.8%. Something to do with the “Phillips Curve,” which the Volcker worshipers now insist doesn’t exist. And then he made no further attempt to reduce inflation. Only in the 1990s did inflation fall to the lower trajectory we now associate with the Great Moderation. Volcker was content to allow 4% inflation, although he now argues that a return to 4% inflation would be awful.

So the Fed has a new set of myths to replace the Phillips Curve. And as a result of these myths they are gradually driving inflation expectations lower and lower. They were supposed to stop at 2%, but it now seems that if low inflation is good, even lower inflation is better. Look closely at the graph above and you’ll see expected inflation has fallen below 1.5%. Some people at the Fed (like Chicago President Evans) would like to see more stimulus, even if it meant 3% inflation. But the Fed is an institution with a momentum of its own, and it’s not clear that even Bernanke could turn it around (nor whether he wants to.)

This won’t last forever. Economists will eventually see that Fed policy is causing all sorts of damage to the economy–and the federal budget. When that occurs another Volcker will finally call a halt to the “Great Disinflation.” Let’s hope this time we finally get it right—5% NGDP growth, level targeting.

Update: After I wrote this I realized my comments on the Phillips Curve seem inconsistent. I was criticizing the idea of a long run trade-off, not the short run trade-off we saw in 1982.

PS. No offense to rhinos, one of my favorite animals. I like old things, and the rhino head reminds me a bit of what the dinosaurs must have looked like. Any comments about their inability to change direction are not meant to be accurate, but merely reflect the way humans perceive them.

Tags:

24. September 2011 at 05:50

The fact that the Fed is slow to change direction (“inertial”) shows up over and over again in the data. I don’t this this is particularly controversial. I can think of lots of reasons – they don’t know the real state of the economy, so they act cautiously; Policy acts with 12-24 month lags; Normally they ony control the repo market, while trying to tie down expectations in the term market.

And actually changing their policy decision framework – the discussion of inflation targets has been around for a very long time and even now is only “informal” – moving the policy framework takes as you point out, decades. WSJ reported this week that some FOMC memembers like Evans are weighing employment / unemployment targets to communicate policy. This is controversial inside the Fed because… um… maybe they’ve never heard of the empirical Taylor Rule that argues they’ve been informaly doing it for a long time. Do they realize, um, most practicioners routinely use their favorite Taylor Rule specification, plug in an estimate for what the FOMC thinks is the NAIRU and inflation target, and then solves for policy direction. Until the zero bound, it described Fed behavior pretty well. And even if the informal targeting is “implemented” don’t hold your breath for acknowledgement because the FOMC as a body does not like to have its hands tied by rules.

But I am more intrigued by your previous thoughts that the FOMC focuses to much on consensus. Making policy by simple majority would be a step in the right direction IMO because it would not give the extremes so much latitude to set policy direction.

24. September 2011 at 06:02

Don’t you stop a charging rhino by taking away his credit card? 🙂

24. September 2011 at 06:20

“So from 1965 to 1981 inflation and inflation expectations moved relentlessly higher”

The operations of the trading desk begain to be dictated by the federal funds “bracket racket” in 1965. I.e., the FED switched to targeting interest rates in 1965.

“Only in 1981 (not 1979 as many wrongly believe) was there so much disgust with inflation”

No, On October 6, 1979 Paul Volcker, Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve e System promised that the Fed was going to mend its ways. Hereafter the Fed would deemphasize the control of the federal funds rate and concentrate on holding the monetary aggregates in check. We were advised to “watch the money supply” as gold and silver hit all time highs.

“As early as 1968 Phelps and Friedman had shattered the idea of a stable Phillips Curve”

No, it was predicted in 1958.

“He reduced inflation to 4% in 1982, and then stopped”

No for 2 reasons. (1) He never “tightened” & (2) he doesn’t understand money flows – MVt was headed up towards the end of 82 regardless.

24. September 2011 at 07:32

On your first point, I would add that a flat yield curve is bad for banks.

24. September 2011 at 07:36

“Next they looked at data going back to 1952 on interest rates one year into a recovery, and found that the interest-rate spread was an average of nearly FIVE PERCENTAGE POINTS HIGHER”

http://online.barrons.com/article/SB50001424052702303741704576580921026997928.html?mod=googlenews_wsj?mod=googlenews_barrons

“This means that on basic lending operations a commercial bank must earn a NET INTEREST MARGIN of 3.15 percent in order to “break even”

http://maseportfolio.blogspot.com/

Obviously, the level of inflation expecations is unhealthy.

24. September 2011 at 07:40

I’m not an economist, so I can’t be too technical, but to be fair. Low stock prices does not always mean a company is doing poorly. Although I do agree that it doesn’t make much sense right now to say that the banks are the sole determinant of the current fed policy.

I imagine that Kling is referring to the debt-inflation game when he says banks benefit, but I would imagine they’d probably benefit a lot more if they were lending some of that money out, even if inflation skimmed off the top of those interest payments.

24. September 2011 at 07:45

“By the 1970s it was clear that inflation wasn’t buying lower unemployment. But the Fed kept inflating.”

Richard Nixon blamed Fed tight money policies for his defeat in 1960 and, with the help of Arthur Burns, made sure it didn’t happen again. Wage and Price controls were Nixon’s way of dealing with (hiding) the resulting inflation. It did help Nixon get reelected in a landslide in 1972. My point being that politics, as much as economic theory, was a factor.

Likewise, a plausible explanation for Volker’s action are simply that, as a Republican, he was willing to let high interest rates sink Carter’s reelection chances but loosened up, allowing 4% inflation, to enable Reagan’s “Morning in America” reelection. Volker’s inconsistent view that 4% inflation is now unbearable could be based on Obama being in the White House. (FWIW, while the current 9.1% unemployment rate makes Obama’s reelection look like a long shot, the unemployment rate in Aug 1983 was 9.5% and Reagan looked less likely to get reelected. Volker certainly knows that.)

Likewise with Bernanke. I don’t buy that he’s suddenly forgotten everything he wrote about Japan. He knows that unemployment is over 9%. He knows that inflation is below the Fed 2% target. He knows that the economy had significantly slower growth in the first half of the year than the Fed had projected. Yet he’s suddenly slow to do anything, in contrast to his active unorthodox moves in 2008. It doesn’t seem to add up from an economic standpoint. The political piece that Bernanke is a Republican and it seems more plausible. I agree that “operation twist” is too small to provide the needed monetary loosening. It looks to me more like a policy of someone that wants to give the appearance of doing something without really doing something. (I hope I’m wrong and Bernanke suddenly finds NGDP targeting or what ever excuse he needs to loosen.)

I don’t want to overstate the political component, because there are legitimate economic theory and policy disputes, but the political component cannot be ignored, either. Especially when political appointees behave in ways that are inconsistent with previous positions and economic theories.

24. September 2011 at 08:02

Once again, absolutely stellar commentary by Scott Sumner.

Yes, the Fed is fighting the last war; perhaps all large organizations do so.

Add in that Bernanke may have been frightened by the sight of Rick Perry and his hangman’s noose.

Russ Anderson’s comments (above) are sadly plausible.

And I love the rhino too, also my “favorite” animal, although there are so many to love.

24. September 2011 at 08:03

Scott,

I’m curious. Why have a 5% NGDP target instead of say, 7, 9, or 10%? Is there an argument to be made for having a larger buffer against deflation?

24. September 2011 at 08:06

Benjamin,

Yes, I’m reminded of France’s phony war. In the Battle of France, the French military leadership was hastily drawing up new lines of defense, only to hear the Germans were already behind those lines.

That’s the kind of leadership we have in Washington. Getting in front of a crisis is all, but illegal.

24. September 2011 at 08:31

Scott’s periods of Fed ideology look uncannily like recent periods of ideology with regard to the role of government too.

Post-WW2 there was a surge towards economic freedom as the US and UK (typified by Hayek’s Road To Serfdom) looked to differentiate themselves from the National Socliast regime defeated in WW2 and the (international) Socialist regimes in USSR and China. I don’t know about monetary policy in the late 40s and in the 50s.

Relative success versus socialism led to a relaxed guard and an accretion of socialist measures from the sixties onwards, culminating in the rediscovery of Hayek by Thatcher and Reagan in the late 70s – and a turn about with regard to monetary policy, according to Scott.

Success aroud the globe in the later 80s, 90s and Noughties seems to have lowered the free market/anti-war guard again, and the size of the state has grown again in the West. This period was accompanied by massive credit expansion later on rather than massive monetary expasion – although prices did rise continuously.

Without a change in ideology on the size of the state monetary easing is highly risky. It is simply not nearly enough for Scott to say “trust me, UI will be cut back from 99 weeks to 26 weeks as soon as NGDP surges”. The ruling ideology is still heavily statist. A new generation of politicians with a bias to prudence rather than promises of gifts needs to be elected.

Sadly, only serious economic crises seem able to crack statist domination of consensus politics. And that takes time to change, just like the time it takes to change the way the Fed thinks.

24. September 2011 at 08:33

Scott,

Sorry, I misstated my question. I actually meant to ask whether having a higher than 5% NGDP target might not be more insurance against reaching the zero bound, which I realize new monetarists don’t think is a real limit, in practice is, at least politically and/or institutionally.

24. September 2011 at 08:58

All large orgs look like Rhinos or Elephants. Actually, most look worse, Rhinos and Elephants are both quite athletic. Very large ships with very poor small rudders are a better analogy.

I have a different but related question – what would we actually hope the rhino would do?

IF we assume that the Fed can only practically buy certain classes of assets.

AND we assume that both visible and shadow banks are scared and trying to fix their balance sheets and lower risk

SO we have both harsher risk standards and fewer borrowers are really credit worthy anyway

THEN what mechanism short of something “over the top” would actually loosen money enough to matter?

(I think we all agree that simply printing money and giving it directly to people would be dramatic, but seems impractical.)

I suppose the Fed could buy so many treasuries (and for that matter so many high quality muni bonds, etc.) that it forced returns to be negative. That is, stashing your money in a 10 year treasury would cost 1% over the 10 years, or 1% per year. THAT level of purchasing ought to drive money somewhere else. But could we be assured it won’t all end up in safes, mattresses, and FDIC insured accounts?

24. September 2011 at 08:59

I will come to a partial defense of Kling’s Point 1 by asking again, “Why has the Fed not cut IOR?” I claim that they (the Fed) think IOR is helping the banks, by giving them free money on the reserves parked there. Scott objects that tight money actually hurts the banks. I rejoin that when it comes to policy, reality is overrated; the policymaker’s framing of the problem is dispositive. (Would not Rorty agree?) Most people do not really believe in differential equations and live in a quasi-static world, after all. See, e.g. the lump of labor fallacy. In support of quasi-stasis, I re-invoke Scott’s rhino metaphor.

So perhaps Kling’s Point 1 could be re-stated as “current policy is close to what the Fed imagines is good for the banks.”

24. September 2011 at 09:10

The post of Scott is magnific.

Very good also Russ Anderson. I think also that the political factor has a considerable weight. I think Tea Party is using a very dirty play. I don´t know how effective will be this tactic in the elections, but for the economy and the FED´s independence is terrible.

24. September 2011 at 09:17

Scott,

Okay, please ignore my second statement there. More NGDP could be a buffer against deflation is my point. I shouldn’t post comments while on the phone.

24. September 2011 at 09:29

Suppose we had never bought into this “2% inflation is a good idea.”

Suppose that instead we had 3% nominal growth and stable prices.

Then suppose we have a similar screw up and nominal GDP is 14% below trend. We have actual deflation and expected deflation.

Our goal is to get nominal GDP back up to trend.

What is that trend? It is the trend that reflects productivity growth. It is the trend that brings the price level back up to its normal level.

Instead, we have a situation where people don’t like 2% inflation, and still have to put up with 1.5% inflation, which is too high in their view, are supposed to put up with 3% or 4% inflation for some undetermined period of time.

I think the polical benefits of a stable price level trend should not be dismissed.

Perhaps the T-Party would all be focused on keeping the price level down, but I think this would get less traction than fighting a proposal to make the price level rise faster.

24. September 2011 at 09:32

Yes, the Fed is fighting the last war; perhaps all large organizations do so.

My experience with risk management at large and small institutions alike is that human beings spend an inordinate amount of time looking in the rearview mirror. Plus, econometric, credit and mortgage prepayment models are fit to the past. They can’t generate a result worse than history. The really superior risk managers are not worried about those risks, they are worried about the unknown risks. Unfortunately, it’s hard to convince people that the never-happened-before event( ot never happened in 50 years) event is on the horizon. Trust me, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard the “nationwide home prices have never gone down” theory of lending.” or oil can’t go from $100 to $147 to $45 in 6 months…

24. September 2011 at 10:27

‘Instead, we have a situation where people don’t like 2% inflation, and still have to put up with 1.5% inflation, which is too high in their view, are supposed to put up with 3% or 4% inflation for some undetermined period of time.

‘I think the polical benefits of a stable price level trend should not be dismissed.’

Very interesting point, Bill.

24. September 2011 at 10:48

DWB–

Here’s one for you: In the good times, banks were lending to very high loan-to-value ratios on commercial properties and then forming subs to “go higher n the capital stack.” A borrower night have to put up 5 percent equity or less.

Since then commercial properties, in general, have lost half of their value.

Now, with commercial property values values cut in half, banks are chary to lend–although now it is arguably less risky.

Like they say, when the bands are playing in the street, sell. When people are crying doom forever, then buy.

24. September 2011 at 13:07

dwb, I agree about the problem with consensus.

David, Your jokes are as bad as mine.

Flow5, You are wrong about 1979, but that is a common misconception. He did tighten very briefly, but soon reversed course. By early 1981 NGDP growth and inflation expectations were higher than ever.

John Hall, Good point.

Illini, I agree stock prices aren’t perfect, but they are the best indicator we have–certainly better than anything Kling provided.

Russ, Burns was only involved part of the time, so he certainly can’t explain the entire period. Contrary to what many assume, Volcker’s tight money policy didn’t really begin until 1981, after Reagan gave him support. Carter lost because of his high inflation policies, not because of Volcker.

You said;

“The political piece that Bernanke is a Republican and it seems more plausible.”

This makes absolutely no sense at all. The Fed’s horrible decision to to cut rates sharply after Lehman failed ruined the McCain campaign. I notice all three of your conspiracy theories favor the GOP–stay away from conspiracy theories, only the Nixon one is arguably true.

Ben, So we agree on rhinos too.

Mike, Because 5% is plenty high if you do level targeting. deflation is not a problem as long as NGDP is growing at 5%. Ditto for the zero bound (I’m assuming level targeting–we’ve only had 1.4% annual NGDP growth since mid-2008.)

James, You said;

“Post-WW2 there was a surge towards economic freedom as the US and UK (typified by Hayek’s Road To Serfdom) looked to differentiate themselves from the National Socliast regime defeated in WW2 and the (international) Socialist regimes in USSR and China. I don’t know about monetary policy in the late 40s and in the 50s.”

I thought 1946 was when Labour started nationalizing everything.

Bryan, The Fed needs an explicit target, and level targeting–that’s by far the most effective policy.

pct, You may be right about IOR.

Thanks Luis.

Bill, My only reservation about 3% is the scary amount of nominal wage rigidity near zero inflation.

24. September 2011 at 17:01

So Scott, your basic claim (I think) is that if the Fed loudly and consistently **promises** “We will push on the gas until nominal GDP grows 5% per year, and apply the brakes at 6% per year.” that will cause RGDP to grow.

That is, the promise is what matters.

To which I counter, what keeps a cynical main street and home street from going “Oh yeah, how are you gonna do that if I hoard all my cash? And the banks won’t lend to me anyway? And you F***ers will inflate us to death while you are at it, new Fed board members to be sworn in tomorrow!”

Investors/businesspeople/engineers like me don’t care about NGDP. We care about net real return. After taxes, after inflation. Net Real Return versus Risk.

I suppose you might claim that a very great many people behave and vote rather differently from that, fair point.

But I think the folks running big corps sitting on cash, and holding it abroad, think in terms of NetRealReturn.

(Please note that I agree that tight money, negative returns, and other such contractionary and deflationary constructions are very bad. I’m just not persuaded that the “promise and expectations” channel is really that powerful for the economy as a whole, rather than just for wall street.)

24. September 2011 at 20:43

The P.S. is pretty funny to me because it seems the whole philosophy on this blog is based on the idea of the Phillip’s Curve.

25. September 2011 at 05:37

Whether to target nominal gDp or the price level is actually moot. If you target a fixed nominal gDp level – you will end up with level prices. However, targeting nominal gDp is easier.

25. September 2011 at 07:07

Scott wrote “Contrary to what many assume, Volcker’s tight money policy didn’t really begin until 1981, after Reagan gave him support.”

The Federal Reserve disagrees: “Twenty-five years ago, on October 6, 1979, the Federal Reserve adopted new policy procedures that led to skyrocketing interest rates and two back-to-back recessions but that also broke the back of inflation…”

“Chairman Volcker called the October 6 meeting of the FOMC to decide on better methods for controlling money, credit expansion, and inflation. […] Associated with a greater focus on monetary control was a significant widening of the range for the federal funds rate. […] In response to these changes, the funds rate rose sharply, and by year end was close to 14% […] The rise in interest rates led to an economic recession that began in January 1980.”

http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/letter/2004/el2004-35.html

Whether politics influenced Volker’s actions is certainly debatable. Whether Volker acted before 1981 isn’t.

25. September 2011 at 08:14

Bryan, You said;

“So Scott, your basic claim (I think) is that if the Fed loudly and consistently **promises** “We will push on the gas until nominal GDP grows 5% per year, and apply the brakes at 6% per year.” that will cause RGDP to grow.”

You mix up two issues, can the Fed raise NGDP, and does this boost RGDP. I have a zillion posts on both points–look at my recent post that links to them.

Yeah, I think the Fed can do what Zimbabwe did.

Business people care a lot about NGDP, they just don’t use that term. Rather, they discuss how “the economy” will be doing next year, when thinking about investment decisions.

John, Yeah, the short run PC slopes downward and the long run PC is vertical. That’s my blog in a nutshell–it’s also the standard model we teach all our students.

Flow5, Supply shocks boost prices even with stable NGDP.

Russ, Common myth, I’ll do a post.

25. September 2011 at 10:01

Scott, yes with NGDP level targeting 5% might be enough, but what if we keep going as we are now? What if the Fed keeps its current methods, but just raises its inflation target until the economy recovers, and then goes back to 2%? Would it be better in that case to just keep the higher inflation rate, of let’s say 4 or 5% as a buffer?

25. September 2011 at 11:20

“But I am not a rhinoceros mind reader, and its actions were such as to warrant my regarding it as a suspicious character. I stopped it with a couple of bullets, and then followed it up and killed it. The skins of all these animals [rhinos + lions + elephants + buffaloes + grizzly bears] which I thus killed are in the National Museum at Washington”

“The Autobiography of Theodore Roosevelt”

http://www.bartleby.com/55/

25. September 2011 at 13:32

@Russ Andersen,

I think you’re defaming Volcker and Bernanke. Alan Greenspan was a somewhat partisan Republican, but I don’t you can say that about Volcker or Bernanke.

In the first place, Paul Volcker is not a Republican and never has been. He’s always been a Democrat. He was appointed Fed chairman by Jimmy Carter, a Democratic president and has most recently worked for the current Democratic administration. He’s never made any secret of his party affiliation, but as Fed chairman he did not act as a political partisan.

Bernanke is a registered Republican, but he’s never been perceived as a political type. If you Google “bernanke political affiliation” you’ll find articles quoting Mark Gertler, who coauthored several papers with Bernanke, saying “If you read anything he’s written, you can’t figure out which political party he’s associated with,” and that he did not know his close friend’s political affiliation until relatively recently. He also says Bernanke is “not ideological. I could imagine Ben working with economists in the Clinton administration.” Alan Blinder, says similar things.

There have been some fairly partisan Fed chairmen over the years, but I don’t think Bernanke and Volcker are among them.

25. September 2011 at 13:38

Scott,

Might I add a bit of sophistication to Kling’s first point? Current Fed policy isn’t good for the bank’s shareholders and creditors (risk of going under) but it might be OK for the management. Top executives own shares and options but they also receive salaries, bonuses and golden parachutes which are unrelated to the bank performance.

26. September 2011 at 03:09

Labour nationalised a lot in 1946, but mostly it was just a formalisation of the state control from the war years. Hayek warned it would go wrong and it did go wrong. The nationalisation and other controls were a disaster, Labour was thrown out, and many controls were reversed. Ten or more good years followed, in fact we’d “never had it so good”. Hubris, as usual, set in followed by the nemesis of the 1970s.

26. September 2011 at 04:56

Mike, If they aren’t going to do level targeting then yes, if they are, then no.

beowolf, Yes, all suspicious characters should be shot.

Lucas, It’s possible, but that actually seems rather unlikely. Generally executives in highly successful firms do better than those in failing firms. I’m not saying the one’s in failing firms don’t occasionally walk away with too much, but the ones in successful firms do even better.

James, That sounds about right.

26. September 2011 at 11:22

What I found intriguing about the Volker op ed was that unlike most who are busy worrying about inflation, he didn’t seem to worry about things getting out of control. Instead, he was worried that if we decide that a little more inflation would be good, we might decide even more would be good at some point down the road and then chose to aim for yet higher inflation.

If that’s the concern, so what? I’m not old enough to remember, but I guess what Scott is saying is that’s sort of what happened in the ’70s, but if all it takes to stop the trend is realizing that it’s happening and acting, it doesn’t seem like too frightening of a slippery slope.

As for Fisher, was he the one who was on Planet Money awhile back arguing that rates needed to go up at least some because 0% created bad incentives for rates that could be avoided by the messaging associated with small, slightly positive, rates? Because that appearance was decidedly unimpressive.

27. September 2011 at 06:45

[…] have an obligation to solve, then this equation doesn’t even make sense. Here’s what locking in disinflation while U.S. wages stagnate looks […]

28. September 2011 at 14:55

Adam, I agree.

8. November 2011 at 16:09

[…] Scott Summers counters with the “Whig theory” of the Fed: I used to have a sort of Whig view of the history of the Fed. They did all sorts of really stupid things in the Great Depression and the Great Inflation, and then they finally found the right policy. This led to low and stable inflation. The last few years, and especially the last few days, have disabused me of that view. […]