The inscrutable Japanese economy

I recall it’s an ethnic slur to call Asians inscrutable. I hope that doesn’t apply to inanimate objects like economies. This post was triggered by a recent Tyler Cowen post:

Let’s say the U.S. becomes another Japan or for that matter let’s say Japan has become Japan.

I’ve said similar things. But that got me thinking about what it actually means to become “another Japan.”

1. Does it mean we’ll have 4.6% unemployment?

2. Does it mean we’ll have near zero NGDP growth?

3. Does it mean we’ll have 1% RGDP growth?

4. Does it mean we’ll have zero population growth?

What is actually the most distinctive feature of the Japanese economy?

To make things even more complicated, I don’t have a good sense about whether the Japanese unemployment numbers are accurate. One sees films from Japan that suggest their job market is broken. One reads heart-wrenching stories of salarymen who can find jobs, of a lost generation of young people. Perhaps the unemployment numbers are misleading in some way. There are two ways they might be misleading; simply missing a lot of unemployed, or treating many workers as employed who have lousy make-work jobs—say handing out flyers on a street corner to get by.

But the mysteries don’t stop there. If you look at the Japanese unemployment rate you do see the normal ups and downs of the business cycle. You also see no change since 2000. There is no monetary model that I know of that suggests tight money could slow economic growth without raising unemployment. Thus although Japanese tight money might have slowed growth in the 1990s (when the unemployment rate trended upward), the recent slow growth should be due to non-monetary factors (unless the data is wrong.) Just to be clear, it is quite possible (likely in my view) that Japan could get another 2% of RGDP by switching to a 3% NGDP target. But it would be a one-time gain, as their labor market got less rigid. Unemployment might fall to 2% or 3%, but trend growth shouldn’t change.

Here’s another mystery. The tsunami/earthquake/ nuclear meltdown had no effect on Japanese unemployment. None. Industrial production did fall sharply in March (the disaster occurred on March 11th), but then rose sharply over the next three months. The quarterly GDP numbers are fairly weak, but nothing very far outside the “noise” one typically observes during a Japanese recovery, when trend rates are quite low. Certainly nothing like the 2009 contraction, which sharply reduced GDP.

The spring 2011 quarter was down only 0.3%, and it’s not unusual for Japan to have small RGDP declines during economic expansions. The IP numbers suggest the disaster did hurt the Japanese economy, but the GDP and unemployment numbers both suggest that the damage was an order of magnitude less than the adverse nominal shock of 2009. (Remember that Japan had no housing bubble in the 2000s.)

I get more pessimistic every day. But even now I can’t imagine the Fed allowing trend NGDP growth to slow to zero percent, even in per capita terms. So we won’t become another Japan in that respect. But they just might allow it to slow to 3% to 4%, and recall that those numbers are from a very depressed level. That could easily create a decade of Japan-like problems, especially when combined with the labor market rigidities like higher minimum wages and extended UI.

If you talk about how those labor market rigidities might have raised our natural rate of unemployment, progressives will sneer that there is no empirical evidence (there is), and that you are just a mean right-winger who thinks unemployed people are lazy bums. Whenever you read those progressives you should always keep the following in mind:

1. The progressives completely failed to predict that the natural rate of unemployment in welfare states like France would rise from about 3% prior to 1973 to about 10% after 1980, and then stay up there permanently.

2. To this very day, the progressives have no plausible explanation for why this happened in many European countries (not all.)

I’m not saying it will happen here, but I’m also not assuming it won’t. All I do know is that we should pay no attention to what progressives say on this subject, as they are so blinded by their romanticizing of “victims” that they’ve lost the ability to think clearly about labor market issues. Ignore them. But when they talk about the need for more aggregate demand, play close attention. On that issue it’s the right that is increasing blind. They’ve become so entranced by the supply-side that they’ve forgotten that the demand-side is also very important.

I also think it’s very possible that trend RGDP growth in the US slows to 1% per capita, for reasons Tyler Cowen outlined in The Great Stagnation.

A few weeks ago I speculated that interest rates might well remain quite low, and that would lead to relatively high stock prices. I didn’t really intend that as a prediction, but I suppose it read that way. It was meant as an explanation of the yield curve and stock market in July. In any case, if it was a prediction then my low interest rate prediction looks very good, and my high stock price prediction looks very bad. But unless I’m mistaken, doesn’t something have to give? S&P500 companies are earning roughly $100/share (in total) this year and next, and the index is barely over 1100. With even long term rates down to 2%, and zero in real terms, this P/E seems unsustainably low. If things kept on this way wouldn’t stocks be a much better investment than bonds? That tells me the market expects a recession that will reduce earnings well below $100/share for the S&P500. And we all know what happened to the Japanese stock market after 1991. Bonds were the place to be.

No real answers here, just some puzzles I’ve been thinking about. Comments are welcome.

PS. Japan and Italy are the two countries that slowed the most from the booming 1950s and 60s, to the sluggish 1990s and 2000s. They both have big public debts. I vaguely recall that years ago The Economist pointed to a number of surprising similarities between these two seemingly dissimilar countries. One is that unlike other western nations, they tend to keep re-electing the same government, even when the economy is in lousy shape. There’s a strange fatalism in their politics. I can’t help thinking that this partly explains the sluggish pace of economic reform in the two countries. Japan’s certainly not poor, but given their legendary work ethic, social cohesion, and high educational levels, it’s surprising that it’s not richer. I wonder if that Economist article is online somewhere . . .

PPS. Many people worry that the Fed could become impotent, just like the BOJ. But the real danger is that the Fed will become content with 3% NGDP growth, just as the BOJ is content with near-zero NGDP growth.

Tags:

20. August 2011 at 10:13

I’m re-posting this, because it is specific to this post:

“But too much of the debate is still around financial valuation, as opposed to the underlying intrinsic value of the best of Silicon Valley’s new companies. My own theory is that we are in the middle of a dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies are poised to take over large swathes of the economy.”

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111903480904576512250915629460.html

Ten years from now you will all be finally ADMITTING the effect of FREE on the “theory” of Macro.

As in, ANY AND ALL price supports of any kind must hunted down and killed in order to grow your economy.

We’ll use a NGDP level target of 2%, and we’ll race to deflate prices at every possible step.

We’ve got to meet China in the middle.

——

I want to hit this again, and again, and again…

It is REALISTIC to say we want 2% falls in real prices YoY and 2% NGDP. We have to be able to imagine that things are becoming free.

Look, the biggest growing prices / parts of the of the economy ten years ago were Education and Healthcare.

But We could realistically see Education prices drop % per year for the next 20 years.

We could realistically see the price of government service (total compensation to public employees) drop 5% per year for the next 20 years.

We could totally see the amount spend on of healthcare freeze for the next 20 years.

you: “help I think I’m having a heart attack!”

mommy from home says: “place your hand on the medic alert tablet.”

mommy from home says: “no, you are not having a heart attack.”

doctor says: “sir you are only allowed to receive drugs out of patent and you are only allowed to receive X-Rays.”

—–

When people are carrying around smart phones connected to the Internet, over time, the real costs (based on time spent working to get X) go down with a force no one here wants to admit.

The laws of the digital are vastly different from the laws of the atomic.

What doesn’t change is the premium that new technology MUST receive in the atomic space.

What does change is that every new digital thing is basically cheaper than the last one.

Finally, each year the digital take s bigger piece of the economy.

Prices (time worked) of X go down by nature. If there psychological need to print money, that’s fine, but:

1. Anything that tries to artificially pump up real prices is morally bad. NOTHING is supposed to worth MORE of your time.

2. If someone isn’t committed to #1, they don’t really get to have an opinion.

20. August 2011 at 10:51

What is actually the most distinctive feature of the Japanese economy?

Message discipline. Tokyo-based journalist Eammon Fingleton has made this point for years.

“Surprising though this may appear to unacclimatized Westerners, all the evidence is that the Japanese economy’s true growth performance has been systematically, if counter-intuitively, understated in the last twenty years.

“For Japanese officials this is a matter of national security: Japan’s previous image as the juggernaut of world trade had proved dangerously counter-productive by the late 1980s. Since then the myth of an often absurdly dysfunctional Japan has been assiduously projected into the Western press. The result is that Western policymakers who once feared Japanese economic expansionism switched to pitying the “basket case.”

“At a stroke, the once-intense diplomatic pressure on Japan to open its markets all but disappeared.”

http://www.fingleton.net/?p=919#more-919

20. August 2011 at 10:58

” Japan’s certainly not poor, but given their legendary work ethic, social cohesion, and high educational levels, it’s surprising that it’s not richer.”

Scott,

how do you know that the data from countries such as Japan, Italy (and China), are accurate? Countries such as the Soviet Union, Greece etc have proven how unreliable simple accounting can prove when confronted with people in power who have little trouble in bending the facts a little bit.

Just have a look at recent events in Japan and how willing people in power were willing to bend the truth so as to show that nothing was happening and everything was safe?

When there is poor governance and little challenges to those in power, you should be very skeptical of what those people are saying. Japan’s high educational levels remind me of stories of 1000 kg nails produced instead of 1000 kg of nails in the Soviet Union. Aggregate data can be very misleading when countries have poor institutions.

20. August 2011 at 10:59

Scott,

We have been Japan for awhile now: our per capita GDP growth rate has closely matched theirs since 2000. Given that the Yen strengthened by over 30% in real term over that time period, their per capita growth must look even better on a PPP basis. The comparisons of our “dynamic economy” versus Japan’s “lost decade” are way past their expiry date.

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-BbER4e0JwOY/TaSLJHFLZwI/AAAAAAAADdg/Wv11Nlj4dW0/s1600/RealGDPPerCapita_US_Japan_1980-2009.png

Japan achieved a superior economic performance over the decade despite the BOJ’s insistence on a larger and larger NGDP shortfall from “trend”. As for whether their unemployment numbers hold up, I can’t say; but I can say that our U3 number masks both a steep drop in the participation rate and a spike in the U6.

20. August 2011 at 12:04

“There is no monetary model that I know of that suggests tight money could slow economic growth without raising unemployment.”

It sounds like the Austrian model, though.

20. August 2011 at 12:07

“I also think it’s very possible that trend RGDP growth in the US slows to 1% per capita, for reasons Tyler Cowen outlined in The Great Stagnation.” But isn’t your proposed monetary policy predicated on accommodating a trend 3% real growth rate and 2% inflation rate, by keeping expected NGDP growing steadily at 5%? If the real growth rate is going to be not much over 1% henceforth (assuming very slow population growth), shouldn’t your expected NGDP target be not much over 3%, rather than 5%?

20. August 2011 at 12:19

I tend to think that the employment level tells a much clearer story about labour market rigidities than the unemployment numbers. An economy with low registered unemployment and also low levels of employment is unlikely to be prospering. Although, low levels of employment could also indicate a large informal sector.

20. August 2011 at 12:24

Scott,

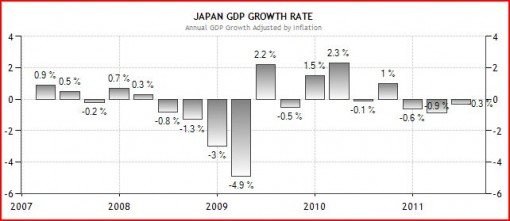

A technical note: The figures in your graph is not “Annual GDP Growth” as its caption says. They are changes from the previous quarter, not annualized.

cf) http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2011/08/12/ritu-jk1121.csv

As for unchanging unemployment, some economists pointed out that decrease in labor force has prevented it from rising. If labor force was increasing as in the US, it would have been on the rise.

cf) The first graph of http://www.heri.or.jp/hyokei/hyokei91/91chochiku.htm

blue line:total population, red line:productive age population, both indexed as 2000=100

And as you may know, we did change the government in 2009, and the things seem to be getting even worse since then… cf) http://www.economist.com/node/14853256

20. August 2011 at 12:27

Excellent commentary. No two nations will be exactly alike–but there are lessons writ large from Japan.

We still have immigration and growing population, they have better citizens and workers. We have fossil fuels, they do not.

But forget details. The big lesson is that tight money does not work–see value of yen.

20. August 2011 at 13:34

Morgan, Any comments on the post?

Beowolf. That’s way too conspiratorial for me. In which sector of Japanese industry is their mysterious growth occurring? Is Toyota making 2 million more cars than they admit to making?

Martin, I don’t know that it’s inaccurate, as the RGDP slowdown coincides exactly with data I do know with 100% certainty are exactly accurate, like the stock market in Japan, and also data that I know is at least 90% accurate, like falling property prices for 20 years. So I think the broad trends are accurate.

Suppose the US government tried to hide the current recession by faking the data, do you think anyone would be fooled? The Soviet problems were clear to everyone who visited the Soviet Union. I recently visited Greece (in 2008)–it certainly didn’t look as rich as the official figures.

David, I don’t understand your comment. How does currency appreciation make the PPP numbers even better?

I also don’t accept your argument that the Japanese economy has done well since 2000, although I’m quite willing to accept the view that monetary tightness hasn’t slowed growth since 2000, as I said in the post.

JTapp, You mean growth is slowed through reallocation?

Philo, No, the optimal NGDP growth target does not depend in any way on the rate of RGDP growth.

Richard, Good point,

Himaginary, Thank’s for clarifying that, although obviously it doesn’t impact my conclusions.

It’s not obvious that a bigger labor force would mean more unemployment. In the US the total number of jobs tends to rise over time at roughly the rare of increase in the labor force. Our labor force has increased about 100 times since 1783, and so has the number of jobs. That’s not a coincidence.

Japan also recently changed government, and things also didn’t get better there. But I think there are differences. In Japan and Italy one never reads about important policy differences between the parties.

Ben, Yes, the tight money has certainly hurt them to some extent.

20. August 2011 at 14:27

Scott,

Perhaps we should *emulate* what the Japanese have been doing? They’ve kept employment reasonably sustained through debt issuance, despite slow growth and some deflation. People keep buying JGB’s.

http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/deflating-the-japanese-horror-story

First and most importantly, Japan is actually considerably wealthier on average today than it was in 1990, contrary to the implication of this article. According to the IMF, per capita income is 16.4 percent higher in Japan today than it was in 1990. This is considerably less than the 21.5 percent growth in the UK over this period or the 36.6 percent increase in the United States, but it is still a substantial gain in living standards. It is also worth noting that Japan’s gain in per capita income was accompanied by a considerable shortening in the ratio of hours worked to population (shorter workweeks and more retirees)….

20. August 2011 at 14:58

Japan’s national debt is now 2.25 x GDP (and its annual deficit is running over 9% of GDP).

If the Japanese were still paying the 5+% interest rates of pre-1992 years, the interest on 2.25 x GDP would be well over 10% of it. But with interest rate basically 0%….

Is the Japanese government practicing financial repression to be able to carry its debt?

(I understand that a significant part of that 2.25 x GDP is intragovernmental, but saving 6% or 7% of GDP in debt service is pretty significant too. And I’m not sure that intragovernmental debt should be disregarded in such calculations simply because the cash/tax cost of the interest is deferred for a while rather than due currently).

20. August 2011 at 15:11

Scott,

When I said Japanese growth was “superior”, I meant, “achieving the same per capita growth as the U.S. with much less unemployment”. The question is how such “tight” policy could produce this outcome. Is it possible mild deflation was a somewhat successful means of adjustment in Japanese labor markets and corporate competitiveness? In any case, I give you tremendous credit for pointing out that the data does not match the conventional wisdom (among economists) on this topic.

The comment, “we might face a decade of Japan-like problems”, makes me wonder though. They had similar growth (per capita), so, what “problems” do we face that we don’t already have? A banking system dominated by consolidated Zombie banks with large unrecognized losses? High fiscal deficits and debt? Repeated, ineffective fiscal stimulus? Repeated, failed attempts to induce a wealth effect by juicing leverage and asset prices?

What the Japanese haven’t had in the past decade is the threat of high and variable inflation resulting from a policy mistake; a boom-bust economy; chronically low domestic savings rates; over-reliance on external financing; high unemployment; etc. Moreover, with the exception of the 1998 scare, their mild deflation has not turned into a potential systemic banking crisis with domestic origins. Given all this, the Bernanke “BOJ” and “It Can’t Happen Here” speeches both seem a bit ironic.

On your other point, I think I confused the PPP and REER concepts.

20. August 2011 at 16:31

Doc, I think this is one of those half empty/half full debates. Yes, in absolute terms Japan has done OK. They are richer than 20 years ago. They are richer than 99% of the humans that have ever lived on this planet. I accept all that. But maybe because I’m old, I view the data you present as very disappointing. Back in 1990 the Japanese were viewed as world-beaters. If you had told me then that over the next 20 years they’d have 16% and the US would have 36% growth in living standards I would have been stunned. Japan was somewhat poorer, and naturally catching up given all their labor advantages. Instead, they’ve fallen further behind the US. I agree that in absolute terms Japan is a rich country, and gradually getting richer. But don’t many Japanese feel that something has gone profoundly wrong with their economy since 1990? Don’t they speak of a lost generation?

The workweek issue is interesting, and applies even more strongly to Germany (also much poorer than the US.) In the case of Germany it seems likely that work disincentives have reduced hours worked, which calls into question whether higher taxes actually raise more revenue. Japan doesn’t have particularly high average tax rates, but on the other hand they work much longer hours than the Germans.

Jim, I’m not sure it helps, because it is the real interest rate that matters. Higher inflation should not affect the real interest rate, at least in the long run.

David, See my answer to Doc. Where I disagree with you is that I don’t see the recent economic performance of the US as being good, and hence I’m not impressed that they have similar per capita growth since 2001. I claimed the hit from tight money was in the 1990s, and Japan is on a new and lower long run growth trend. But in the US the hit from downshifting to a lower NGDP growth rates was in the past ten years. So you are comparing the US in the decade it was hit by the nominal shock, to Japan in the decade after it was hit by the nominal shock (and may have partly adjusted.)

I’m an agnostic on the unemployment data. I’ve read that things in Japan seem much worse than the raw numbers show, but I have no proof. So I simply don’t know. Back in 2007 when we both had 4.5% unemployment, articles about the tragic plight of salarymen in Japan seemed to depict a situation far worse than what average middle-aged workers in America were facing. But that’s a very superficial impression, I hope we get a Japan expert commenting over here. Someone must know if those numbers are accurate.

20. August 2011 at 16:33

Scott,

1. You don’t think there is inflation right now, EVEN THOUGH:

housing prices are SUPPOSED to be getting cheaper – which you refuse to admit / accept.

What this means is that PAST housing price increases happened way too soon, much like the auto sales that happened too soon during Obama’s cash for clunkers idiocy.

So NOW that prices in housing are falling back to where they are supposed to be, you are advocating that gas and food costs explode.

If I were you, I’d want to remove housing costs from the inflation index and focus like a laser on energy and food prices….

BECAUSE it appears that every time consumers see gas prices go up, they go negative on their personal outlook, which freaks out the businesses.

2. All LAST WEEK, we finally had a real conversation about Monetary Policy BN12 (before Nov 2012) and AN12 (after Nov 2012).

Which means your low moans about the empire of a Second Sun, it NOISE, and you know it.

In grown up world, you know that AN12 is when things will explode. Like Augustus Gloop, shooting through the chocolate tube, the pent up market demand for a government in retreat will feel like the Superbowl is being hosted in Amsterdam.

Jesus, Bachman just said she’d lock the doors and turn off the lights at the EPA.

That’s the real shit there baby. Government betas with their tails between their legs wishing they were real men, NOT asserting themselves as arbiters of their betters.

Again, you might not like that exact imagery, but it is certainly powerful enough for you to quit the DeKrugman routine, because deep down, you know it gives you wood.

We are NOT Japan. This is happening because we are NOT Europe. And Obama REFUSES to be Clinton II.

3. I’m sick of Tyler’s GS – he’s a smart guy, but he’s got half the brain of Marc Andreessen.

When I post Marc’s note, that refutes Tyler. Period. The end.

20. August 2011 at 16:43

Scott,

Your analogy concerning Italy and Japan forced me to look at the data and what I discovered shocked me.

In particular I focused on GDP per hour worked. What I noticed was that Japan’s productivity peaked as a percent of the US level around 2000 (about 69%). It has fallen since then but not by much (it was about 66% in 2010). If one believes in convergence (and I do) this implies that Japanese macroeconomic policy, for whatever reason (tight money?), is poorer than our own.

What surprised me was Italian productivity. Italy’s productivity peaked at about 101% of the US level around 1995. Since then it has undergone a precipitous relative decline, to 77% as of 2010. In other words, what the !@#$ is up with Italy?

I know this takes us off the monetary policy failure discussion, but this really surprised me.

20. August 2011 at 16:46

P.S. Among OECD members Italy’s productivity has fallen behind Austria, Australia, Ireland, Spain and Sweden’s over this period as well.

20. August 2011 at 16:53

P.P.S. I left out the U.K. And to be clear, Italy’s productivity was already behind several other OECD members in 1995, including Belgium, Norway, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands and France.

20. August 2011 at 17:10

Doc,

“First and most importantly, Japan is actually considerably wealthier on average today than it was in 1990, contrary to the implication of this article.”

Hardly an accomplishment. Their average GDP per capita growth could be 0% and they’d still be wealthier than in 1990.

Scott,

“There is no monetary model that I know of that suggests tight money could slow economic growth without raising unemployment.”

It’s not a monetary model, but a simple productivity slowdown as a result of catch-up (with no offsetting features) would slow growth without raising the natural rate of unemployment. One could call it a Great Stagnation for a newly developed country.

20. August 2011 at 17:12

Mark A. Sadowski,

“What surprised me was Italian productivity. Italy’s productivity peaked at about 101% of the US level around 1995. Since then it has undergone a precipitous relative decline, to 77% as of 2010. In other words, what the !@#$ is up with Italy?”

One problem is that, economically, Italy is still very much a “geographic expression”. It wouldn’t shock me if the industriousness of the northern Italians is finally being eroded by their status as the host of a very persistant and voracious parasite in their southern regions.

20. August 2011 at 17:12

(I’ll keep it clean, don’t worry.)

20. August 2011 at 17:29

Jim, I’m not sure it helps, because it is the real interest rate that matters.

OK, how about this: Suppose Japan to get out of its malaise targeted a higher inflation rate or NGDP or whatever, with the result that it to increased its bond rate to around 5%.

Bloomberg gives current Japanese longer bond yields as 15-year, 1.45%; 20-year, 1.8%, 30-year, 1.96%.

My bond calculator tells me that if the 20-year bond rate moved from 1.8% to 5%, the 20-year bond would drop in value by 40% to $60, and longer bonds would drop more of course.

In principle this might be good for the economy in general, but even if so, could the Japanese financial system absorb this shock?

The question comes to mind because a decade ago Rudi Dornbusch (Krugman’s mentor) wrote a piece on what could bring on another Great Depression. He missed what happened in 2008 but suggested two things: (1) Major war in the Middle East destroying all the big oil fields to drive the price of oil to astronomical heights, and (2) A run on Japanese bonds when people realize they are junk.

I don’t know about them being “junk”, but if well over 100% of GDP worth of bonds all started a big multi-year price plunge of maybe up to 50% or more on the longest end, I’d think that would have to discomfort somebody. Would the BoJ allow it? If inflation and interest rates moved back up to historically normal levels, how could they avoid it?

I’m just looking for a rational, self-interested reason to explain why the BoJ wants to keep inflation at 0% or below and interest rates so low.

20. August 2011 at 17:50

Jim Glass,

I think there is an irrational attraction to 0% inflation, particularly for people who think in purely macroeconomic terms and therefore ignore the function of prices as signals. The same thinking was behind the traditional Keynesian backing of wages & prices policies: if prices are just exogenous sociological phenomena deteremined by a Marxian kind of power-struggle, then who cares if you distort them? Indeed, if you reduce differentials, then you’re painlessly accomplishing “social justice”.

20. August 2011 at 17:53

W.Peden,

wrote:

“(I’ll keep it clean, don’t worry.)”

I gathered that the implication that being Sicilian or Calibrian is analogous to a venerial disease was purely accidental. But thanks for the clarification anyway.

20. August 2011 at 18:26

Karl Smith has some useful numbers on Japan. Youth unemployment, not so good. Better than many other developed countries, but note the continuous upward movement from 1993-2003.

On productivity, down here in Oz, productivity has fallen (pdf) from 91% of US levels in 1998 to 84% now: not a huge drop but (more than) a reversal of previous gains.

20. August 2011 at 18:33

Mark S and W.P: I believe the relevant (Northern) Italian expression translates as “Africa begins at Rome”.

The Lega Nord basically exists to represent the desire of the prosperous North to stop paying for the South. (The late unlamented Jesse Helms’ “not pouring money down foreign rat holes” sentiment domesticated.) Why folk believe me that decades of group A paying for group B will build social solidarity–particularly when it apparently turns into an endless stream of somehow-it-never-gets-better-transfers–is beyond me.

20. August 2011 at 18:43

A friend who is active in the Lion Rock Institute, a Hong Kong think tank, made the observations to me that

(1) deflation/no inflation in Japan increases/preserves the income of the increasing number of old folk: i.e. there may be quite a constituency for “price stability”.

(2) As baby boomers retire and want to live off assets, there may quite a collapse in the tail end of the yield curve: would that affect its usefulness as a forward indicator?

21. August 2011 at 02:58

Scott, you said:

“Suppose the US government tried to hide the current recession by faking the data, do you think anyone would be fooled? The Soviet problems were clear to everyone who visited the Soviet Union. I recently visited Greece (in 2008)-it certainly didn’t look as rich as the official figures.”

I don’t know much about the US, (I live in Europe: Netherlands), however unless the country is in really a bad shape, I don’t see how I’d notice that unemployment had gone up 3-4%. Anecdotal evidence is hardly sufficient to challenge such aggregated data.

I think it also matters a lot on how consumption/income is distributed in a country whether you’d notice that the aggregate data is significantly off.

From when I visited Greece, I considered it to be a second world country comparable to post eastern bloc countries such as the Czech Republic in per capita Income. Considering that CZ has a lower Gini than Greece and less Income ($5.000), this explains for me why the income differential is not all that visible.

Another example, I’ve lived in the UK for some time and the impression I got was that outside London, people were significantly poorer and I’d almost consider the UK a second world country. They have a slightly higher income than Greece (by about $5.000), but income and probably consumption is less equally distributed. Go all the way up to Scotland and you’ll find a ‘country’ with one of the lowest life expectancy in Europe in a supposedly wealthy country as the UK.

Last example, something you’re probably better capable of judging than me, but I’ve been to both Sweden and Denmark and to the States (NY). Both countries are significantly poorer than the US, by about $10.000 on a per capita basis. This is a huge difference, comparable to the difference between Sweden and the Czech Republic. However, when I went outside Manhattan, I did not exactly have the impression that Americans were that much richer than Swedes. If I wanted to be provocative, I could even defensibly argue that they are in fact poorer. The reason for this is that Income and consumption is substantially less equally distributed in the US than in Sweden and Denmark.

I however trust most (not Greece) of these data over anecdotal evidence, as the mechanisms are in place and the culture is such that fraud with those data is highly unlikely.

As for the Soviet Union, the reason for me mentioning it was that in Samuelson’s textbook, so I’ve heard, it was ‘predicted’ that the SU would overtake the USA based on their aggregate figures.

21. August 2011 at 06:18

Morgan, You said;

“Which means your low moans about the empire of a Second Sun, it NOISE, and you know it.

In grown up world, you know that AN12 is when things will explode. Like Augustus Gloop, shooting through the chocolate tube, the pent up market demand for a government in retreat will feel like the Superbowl is being hosted in Amsterdam.

Jesus, Bachman just said she’d lock the doors and turn off the lights at the EPA.

That’s the real shit there baby. Government betas with their tails between their legs wishing they were real men, NOT asserting themselves as arbiters of their betters.

Again, you might not like that exact imagery, but it is certainly powerful enough for you to quit the DeKrugman routine, because deep down, you know it gives you wood.”

I like the exact imagery. That’s the best part of your writing. Regarding the ideas . . .

Mark, Surely those long run productivity numbers reflect supply-side problems, not monetary policy. I also question the accuracy of the numbers–I doubt Italian productivity levels ever reached US levels, except perhaps in manufacturing.

W. Peden, Yes, you expect a catch up phase to end at some point. But two things surprised me about Japan. First, the catch up ended at levels far below US levels. Second, they have actually been falling further behind since 1990.

Lorenzo, I’m surprised by the Aussie productivity numbers. I believe they’ve had faster real growth than US, so obviously it’s due to the drop in hours worked. I suppose in the US the drop in hours has been heavily tilted toward the less productive workers–which boosts our measured productivity, but not our actual productivity.

The yield curve can be a flawed indicator, but in its favor it’s predicted pretty well for 17 years in Japan, hasn’t it? So I wouldn’t be quick to dismiss it’s implications, indeed my guess is things will stay the same for an “extended period.”

I also heard the same joke about Southern Italy.

Martin, Those are interesting points. Regarding Scandinavia, let me throw out a hypothesis. We seem poorer because America is much uglier. If you look at almost any materialist measure, Americans are much richer than Europeans. We tend to have more cars, appliances, bigger homes, etc. We “consume” more health care. And even income inequality doesn’t explain it all. Those on Medicaid often consume more health care than Europeans. Many inner cities spend more on public education than Europeans. I read that Oslo is the only city in Europe where the average house is as big as the average poor person’s house in America.

If I were to travel around upstate NY I might reach the same conclusion as you, it looks more depressed than Scandinavia. But you should also recall that upstate NY is a relatively depressed part of America. The towns also look ugly. And much of NYC itself is quite ugly compared to European cities. Most Americans live in boring but convenient suburbs that Europeans have no reason to visit.

Boston is much less nice looking than Paris. But few people live in Boston. I live is a beautiful suburb called Newton, which is orders of magnitude more attractive than Paris’s suburbs.

On noticing a recession; I am not just talking about people one knows who are unemployed–but also all sorts of other data. The budget deficit balloons during recessions, for instance, even with no stimulus. Stocks and bond yields fall. Steel production falls. So do auto sales. Etc, etc. And if the government tries to high aggregate housing data, you’d notice a drop in lumber sales, or housing prices. There’s a whole web of data that fits together–it can’t all be faked.

Off topic, That’s why I’m skeptical of those who deny the high Chinese growth rates. On my frequent visits to China it looks exactly like I’d expect a country to look that was growing at 10%.

21. August 2011 at 07:35

Scott, while tax as % of GDP in Japan may be low, this is mostly due to myriad tax breaks for almost all SMEs, have very slim margins and would be economically unviable otherwise (this is one way the Japanese government “props up” employment while structurally distorting the economy – many industries there should be more consolidated but are still ruled by mom-and-pops. You can see this in Korea, a country I know more about, to a lesser degree). Also, the employment rate in Japan is actually lower in the U.S., at 57% vs. 58%. So I’m not sure the Japanese jobs machine is really more powerful in 2011.

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/roudou/154.htm

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t01.htm

On the other hand, marginal tax RATES, which I think impact incentives more than sheer tax as % of GDP, are actually very high. The top income-tax rate is 50% when you add national, prefecture, and municipal. This is only for those earning ~$200k+ (who may well be the people with the most “potential production” e.g. from working extremely hard in a startup if the potential reward is big enough); from $100-200k the rate is ~43%. Corporate income tax is also extremely high at 42% all-in (local + national)

http://www.jetro.go.jp/en/invest/setting_up/laws/section3/page7.html

http://www.worldwide-tax.com/japan/japan_tax.asp

Worst of all, payroll tax (split between employer and employee) is a staggering 26.1%. Your income tax is based on your gross income with only some of the payroll tax deducted. So you could say true marginal income tax rates are even higher, maybe 60% (not sure exactly).

http://www.jetro.org/documents/fact_sheets/f_sli.pdf

http://www2.gol.com/users/jpc/Japan/taxes.htm

Another reason for Japan’s LT low growth lies in the bizarre incentivization to use or be contract workers. It is impossible to fire regular workers without VERY strong cause (e.g. showed up drunk on the job) but contract workers can be dealt with much more flexibly. The catch: no contract worker can be kept on for more than 2 years. Korea has a similar asinine rule. In any case, this goes directly against the Japanese tradition of sophisticated company training and human-capital acquisition. Since 1985, contract workers (remember, cannot be kept on for 2+ years without giving them lifetime employment) have gone from near-zero to 30% of jobs.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haken-giri

http://www.debito.org/rightsofrepeatedlyrenewed.htm

Another perverse reason many women become contract workers is a desire for a part-time job due to a stupid tax loophole – women with incomes over 1.03m Yen and then 1.3m Yen can’t take two marital income tax deductions. In Japan, part-time work is nearly always done under the more flexible “temp” laws since a “normal” job entails so many restrictions on firing as well as costly mandatory pension contributions.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxation_in_Japan

There are plenty of other stupid tax-code-created distortions like being able to live in company housing tax-free. But this often consists of dorms or a small room. In any case, it’s often way too small to even think about starting a family. This is probably one reason why men now get married at age 30.4, and women 28.6 (and rising). This is definitely a factor in Japan’s rapid aging.

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c02cont.htm#cha2_4

In conclusion, my opinion is that a total lack of neoliberal reforms since the 80s – and even going backward in some areas, like using the BOJ balance sheet to buy back bank cross-shareholdings (a perverse system itself) that fell in value, preventing banks from foreclosing on SMEs, – is the true culprit here, in combination with a sustained low birth rate which is caused partially by many of the distortions created by bad policies. I tend to think that fundamental imbalances and distortions like this would actually be “numbed” for a time by rapid monetary growth (e.g. South American countries in the 70s) which may (Chile) or may not (Argentina, Brazil for awhile) catalyze some sort of reform process.

Koizumi’s administration did undertake some good neoliberal reforms (e.g. allowing upzoning in Tokyo with some conditions – http://www.japantoday.com/category/lifestyle/view/tokyos-iconic-buildings-being-lost-to-zoning-laws or promising to privatize the Postal Bank socialist capital-allocation machine) but successive governments have, if anythihng, backtracked.

21. August 2011 at 08:59

Regarding:

>Here’s another mystery. The tsunami/earthquake/ nuclear meltdown had no effect on Japanese unemployment.

Many jobs lost in that area where the tsunami/earthquake/ nuclear meltdown hit. While, almost the same amount of jobs created in the other area. Jobs transferred to the rest of Japan.

cf.

http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/itiran/roudou/monthly/23/2304r/dl/pdf2304rchiiki.pdf

21. August 2011 at 10:04

Scott,

In response to your question to me above, no. I’m reading Murray Rothbard’s The Mystery of Banking to try and understand the Austrians. He lists the U.S. 1839-1843 period as an example of low unemployment in the face of (very rapid) monetary contraction:

“But didn’t the massive deflation have catastrophic effects–on production, trade, and employment…? Oddly enough, no…real investment fell by 23% during four years of deflation, but real consumption increased 21% and real GNP increased 16%…most of the deflation period was an era of economic growth.”

ABCT says that you can have tight money and robust economic growth (RGDP) along with the accompanying deflation. You can also have an expansion of bank credit and a boom/bust cycle without an increase in prices (prices would just be higher than they would be otherwise).

21. August 2011 at 10:49

Jtapp,

Wouldn’t the HUGE inflow of immigrants at that time have a factor in that? If you look at RGDP per capita growth in that period, it was around the same as NGDP growth (and was contracting unless you include the turnaround year of 1843) while population growth was nearly 3%, which was what was driving the growth.

So the economic meltdown was being offset by a rapid increase in the number of mouths to feed, hence the rapid growth in consumption.

The US exited this period of relative stagnation as the 1840s went on, catching up with RGDP per capita growth of just under 3%, while NGDP growth was around 9% and population growth was even faster.

It’s hard to see what relevance this experience has for a modern Western economy, except perhaps that per capita stagnation is the lot of a country with low NGDP growth…

21. August 2011 at 10:51

(Of course, ABCT may predict that immigrants will rapidly flow into a country during such periods, technically boosting RGDP growth, but I doubt the microfoundations of such a model.)

21. August 2011 at 10:54

W. Peden, you would know better than I. Rothbard never delves into any of the other factors playing a role. I was simply pointing out an example the Austrians give of tight money accompanying low unemployment and robust growth. Scott said he knew of no monetarist model that could show such, and I said it sounded Austrian.

Another interesting historical footnote is that the Democrats were the hard-money people back then while the Republicans were very much not.

21. August 2011 at 10:55

Eh, note on the above comment– Scott didn’t say “robust growth,” only “low unemployment” as obviously Japan isn’t experiencing robust growth.

21. August 2011 at 12:31

*Murray Rothbard’s The Mystery of Banking …lists the U.S. 1839-1843 period as an example of low unemployment in the face of (very rapid) monetary contraction:*

*”But didn’t the massive deflation have catastrophic effects-on production, trade, and employment…? Oddly enough, no…real investment fell by 23% during four years of deflation, but real consumption increased 21% and real GNP increased 16%…most of the deflation period was an era of economic growth.”*

*ABCT says that you can have tight money and robust economic growth (RGDP) along with the accompanying deflation.*

~~~

Wouldn’t the HUGE inflow of immigrants at that time have a factor in that? If you look at RGDP per capita growth in that period, it was around the same as NGDP growth (and was contracting unless you include the turnaround year of 1843)

Real GDP per capita via EH.net:

1838: 1,885.41

1839: 1,883.69

1840: 1,837.66

1841: 1,826.35

1842: 1,831.47

1843: 1,868.92

That’s still down after five years.

21. August 2011 at 12:50

Jim Lgass,

Good point, I should have started in 1838.

Obviously, nominal factors aren’t anything, but I think we can safely assume that US growth during that period was purely due to population growth. This was during a period where, otherwise, US per capita growth was very impressive. Money matters.

21. August 2011 at 13:23

Sean, Thanks for that excellent survey of Japan. I certainly agree that a lack of neoliberal reforms is the key to structural problems. It’s shocking that the Japanese government collects so little revenue with those Swedish style tax rates. The system must be very inefficient.

BTW, the US has higher marginal rates than many realize. Our corp. tax rate is nearly as high as Japan’s and higher than all other developed countries. Our personal rate nominally tops out at 35%, but actually goes up to almost 50% with all the add-ons like the Obama-care tax, and income taxes in places like New York and California.

Do you think the true unemployment rate is higher than the reported figures, or is all the complaining in Japan due to the fact that the young are forced into those temp jobs?

H Wasshoi, Thanks for the info. It’s even more surprising to me how little the overall GDP fell. Just another example of Adam Smith’s famous saying:

“There is a great deal of ruin in a nation.”

I.e. real shocks don’t hurt economies as much as you’d expect.

JTapp, We were an agrarian economy back then, so I imagine sticky wages weren’t much of a problem. There were very few factory jobs, or jobs in big corporations.

W. Peden, Good point, it’s NGDP that really matters.

If NGDP growth was fast, then money wasn’t tight. China also grew fast with deflation in the late 1990s. They had fast NGDP growth.

Jim Glass, So is Rothbard wrong in his assertion that we grew fast in real terms?

21. August 2011 at 13:51

“Another interesting historical footnote is that the Democrats were the hard-money people back then while the Republicans were very much not.”

One of the sub-reasons I’m as cocky as I am about there being ONLY ONE plausible method of Scott getting the kind of change he wants is because I read the comments at progressive sites whenever someone mentions printing more or increasing inflation.

Rank and file Dems are still VERY MUCH hard money players, and even the the far right skews probably 60% against.

Unemployment only effects a few people. 5 out of 100.

Inflation affects us all. Particularly the likely voters.

21. August 2011 at 13:53

sorry, far left. The far right just wants to see government fail, if Scott’s plan can help that, they’ll support it.

21. August 2011 at 15:04

I’ve worked on Japan as an academic economist for 25 years, so being brief is hard….

1. Japan like all countries has a finite data budget, but quality is comparable in most areas with the better end of the OECD (fiscal data inclusive of local government is a possible exception). However, unemployment data is almost never comparable internationally because the framing of survey questions differs (what is a job, what is the boundary between unemployment and not in labor force). By US standards unemployment may be understated a bit, but careful comparisons don’t find huge differences (see US BLS studies).

2. The recovery from a real estate bubble isn’t quick, and monetary policy seems not to help. Add to that population decline which keeps real estate prices falling in most of the country (rural areas depopulating). But the economy did begin growing from 2002Q1-2008Q1 with an attendant improvements in most labor market indicators. But it was from a level of high excess capacity and with the biggest cohort at the top of their careers. Lots of contingent hiring, with shifts towards “regular” jobs approaching 2008 as excess capacity was soaked up. But in a sense the labor market was very dynamic, lots os structural change, lots of changes across industries, lots of big firms shrinking. It’s hard to fire “tenured” male workers in unionized firms — but that is perhaps 1/5th of the labor market, and it’s hard, not impossible, lots of “voluntary” retirement, particularly when the union goes along.

3. By 1980s standards, Japanese monetary policy should have left the country in a downward spin of hyperinflation. Not the case. Fiscal policy was inconsistent.

4. Net debt is 40% of gross debt. Most of that is held by banks because they can’t find borrowers (disintermediation plus balance sheet rebuilding plus low levels of construction). Plus 95% is domestically held. Hard to construct a scenario in which Japan can’t fund national debt except one of strong growth the boosts nominal interest rates. But that will make tax receipts skyrocket and will facilitate the realization of the underlying political consensus to boost the consumption tax from 5% to (eventually) 15%.

5. Tax games? Nothing like the US, outside of the small retailer and farm sectors where tax evasion is the norm. Of course business is lobbying for lower taxes, but it’s hard to see behavior to suggest that a shift in marginal rates will do much.

But I must prep now for my China course — I can’t round up enough students for Japan whereas I have two full sections for China…..

mike smitka, washington and lee university

21. August 2011 at 15:16

Scott, as of 2009, the construction industry employed 5.2m Japanese.

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c12cont.htm#cha12_2

This is only ~1m fewer workers than the late 80s (I think it peaked out at ~9.5% of a labor force in the ~65m range). Meanwhile, demand for residential, commercial, and retail newbuilds from private industry has contracted far, far more than the 15% fall in workers. “Bridges to nowhere” – low-ROI gov’t infrastructure spending – picked up much of the slack and effectively preserved jobs in a very Keynesian fashion.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/06/world/asia/06japan.html

http://www.amazon.com/o/ASIN/0809039435/?tag=dp-us-20

Part of the reason behind this: in the construction industry, all jobs are “normal” or extremely protected. Without government demand, politically-powerful construction companies would have gone bankrupt in droves due to inflexible labor costs (I believe many did fail despite gov’t stimulus).

In this sense, I agree with your argument that loose monetary policy without a “centralized capital allocation demand uplift” is preferable to “fiscal policy” as practiced by Japan in the last 20 years, and the U.S. in 2009-10 (find shovel-ready infrastructure projects and just build baby build).

Also, the 2.44m-strong “agriculture and fisheries” category would likely be much, much smaller without the government tariff and price-support system. E.g. beef imports are taxed at 38.5% when world prices are high and 50% when world prices are low and rice is taxed at 402 yen/kg which vs. current spot price of 45 yen/kg.

http://www.customs.go.jp/english/tariff/2011_8/data/i201108e_02.htm

http://www.customs.go.jp/english/tariff/2011_8/data/i201108e_10.htm

Of course, jobs MAY be created in other sectors if/when these workers found themselves jobless. In truth, though, these are the least-educated segments of the Japanese society and, in the case of farmers/fishermen, often quite elderly.

In summary, out of 60m current workers, nearly 8m work in industries that would be much smaller today without the government’s direct support of VERY uneconomical activities. This is basically the definition of make-work though it is shrouded in slogans like “food security” and “improve the countryside” (through new bridges and dammed rivers).

Anecdotally, my Japanese friends also say that there is a definite dearth of good jobs compared to the number of good applicants. Many smart university students are now becoming cram-school teachers when they graduate, preparing other students for middle/high school and college entrance exams. (Zero-sum games to some degree as some of the knowledge tested is purely rote, though I do agree that memorization is a skill in itself and does train the brain to some extent).

Anecdotally, at least, this is one of the only sectors that is hiring without a protracted interview process and the requirement of years of commitment from both applicant and employer. Of course, it is difficult to call this a “career” especially to ambitious graduates. It is harder to change careers midlife than in the U.S. as well, though I’m less familiar with Japanese in this age bracket. In summary, the job market is certainly more rigid and likely has fewer “opportunities” at all levels (particularly the lowest) including the U.S., despite printing a lower headline unemployment rate.

21. August 2011 at 17:09

Mike Smitka,

“The recovery from a real estate bubble isn’t quick, and monetary policy seems not to help.”

I respectfully disagree. The British recovery from the nasty early 1990s post-real estate bubble slump was very quick and followed by a period of unprecedented expansion. As soon as the ERM (allegedly Exchange Rate Mechanism, more plausibly Eternal Recession Mechanism) approach was abandoned in September 1992 and monetary policy loosened, Britain began a forgotten recovery with falling unemployment, rapidly falling deficits and excellent growth.

The most vital monetary policy steps seem to have been the announcement of a 1-4% inflation target and the consequent fall in bank rate.

Recoveries from real estate bubbles are prolonged IF monetary policy is not accomodative, because tight money forces the private sector to do a particularly painful kind of deleveraging. The main lesson of Japan for monetary policy seems to me to be that expectations are very important and that it is the quantity of money (and its velocity) which should be the focus, not interest rates.

21. August 2011 at 18:28

Late post…but a couple of quick points.

1. I saw a comparison (a long time ago) of the unemployment survey methodology. I can’t remember the specifics exactly, but in the U.S. they ask if you have looked for work in the last 6 weeks. In Japan,they ask if you have looked in the last week. They study suggested that if you use U.S. methodology, male unemployment in Japan goes up 60% and female unemployment doubles.

2. Sean and Mike have some very good points.

3. There is a lot happening in the grey economy. When taxes and regulation become unbearable, people figure out a way around this…..i.e. cash businesses, which is why Tokyo now has 3 times as many Michelin starred restaurants as Paris. Nominal tax rates have fallen, but enforcement has gotten stricter and evasion has decreased so average effective tax rates are probably a lot higher.

21. August 2011 at 18:44

Sean,

Good commentary on the tax code and unemployment. One thing that I think is a particularly big problem is the tax on capital. other than evasion, which is prevalent, it is very difficult to avoid double taxation on profits. LLCs and S Corporation are virtually non-existent and bonuses paid to directors (i.e. owners for an SME) are non-deductible to the company.

No one has figured this out, but when you have asymmetric returns on capital as is the case with SMEs (a lot of losers and a few winners), very small changes in the tax rate on capital have huge impacts on average expected after tax returns. This is killing Japan…. except for cash (i.e. easy tax evasion) businesses like restaurants, beauty saloons, spas, etc., which are booming.

21. August 2011 at 23:13

Scott,

The link between GDP/capita and living standards is pretty weak, and cross country comparisons that equate higher GDP/cap with being “richer” may be technically correct but the word rich has quite a different everyday meaning, much closer to “higher standards of living”. I do not believe that meaningful comparisons can be made:

Are Luxemburgers twice as rich as Belgians? On a GDP/cap basis they are, but not in livin standards. And they can shop conveniently across the border, like the neighbours can conveniently apply for jobs in Luxemburg, and commute from their own country.

I think the employment share of GDP is a much better standard for comparison and the ratio of employment share to personal consumption. Give that a realistic PPP treatment and you can compare standards of living -somewhat- Relative to the US, China shrinks, Japan grows and the Singaporean miracle disappears…

22. August 2011 at 04:59

You are thinking of this like a macroeconomist Scott. Instead think of it as if you magically had firm level data.

What if suddenly no one was allowed to go bankrupt or to fail, what would happen? Well, creative destruction would cease and intense stagnation would be the result. This is the story of Japan. 20 years is long run enough that you can’t just use NGDP to try to explain what happened to them, as its still happening.

22. August 2011 at 14:51

Morgan, Unemployment affects far more than 5%, I’d guess 20% to 30% have been unemployed or underemployed recently.

Mike, You said;

“The recovery from a real estate bubble isn’t quick, and monetary policy seems not to help.”

How do we know this? Money’s been tight in Japan for 20 years.

Thanks for all the other information on Japan.

Sean, That’s supports my hunch that the job market is much worse than it appears from the unemployment rate. Another blogger recently produced a graph showing job growth in Japan lagging far behind labor force growth.

W. Pden, I agree.

dtoh, Those are excellent points.

Rien, Most international comparisons are already done on a PPP basis. And if you do so China and Singapore look much better. The US moves way ahead of Europe.

I agree the Luxembourg data is distorted by its role in finance.

Doc, If you read my post you’d discover I argued that NGDP can’t explain much of the Japanese situation–I estimated it cut 2% from GDP.

22. August 2011 at 14:59

Doc Merlin,

“What if suddenly no one was allowed to go bankrupt or to fail, what would happen? Well, creative destruction would cease and intense stagnation would be the result. This is the story of Japan.”

That’s the argumentum ad absurdum. But plenty of firms in Japan have gone bankrupt since 1990. If it’s the protection of (some) banks that matters, why would the stagnation be quite so widespread and pronounced?

The suppression of creative destruction is an important part of the story, but not the whole story.

23. August 2011 at 17:00

Moody’s just downgraded Japan’s debt a notch to AA3.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-08-23/moody-s-lowers-japan-s-government-credit-rating-to-aa3-outlook-stable.html

24. August 2011 at 22:53

Scott,

I know what PPP adjustment does. My point was that the wage share of national income per capita is a better indicator of living standard differences than GDP as a whole. Singapore’s and China’s shares are very low, compared to Western Europe (excl Holland and Ireland), as a result of systematic wage suppression. Nevertheless, I think that living standards in Singapore may well be the best in urban East Asia (even better than Japan), because of the extraordinary value for money of a broad range of public services (incl housing, education and healthcare). PPP does not catch that…

10. September 2011 at 07:36

Rien, I can agree with that. One reason there’s such value for money in health care is it is purchased out of pocket, unlike in the socialist United States, where someone else almost always pays.

18. August 2015 at 11:51

[…] have I heard something like this before? Here’s Scott Sumner in […]