Maybe it’s my jet lag . . .

and my cold . . . but I just don’t get this Conor Sen Bloomberg article:

Trump Wants the Fed to Roll Back the U.S. Economy

Higher interest rates could revive manufacturing and exports. That will hurt consumers and workers.

I’m only at the subtitle, but already lost. How do higher interest rates boost manufacturing and exports? And if they did, why would that hurt workers?

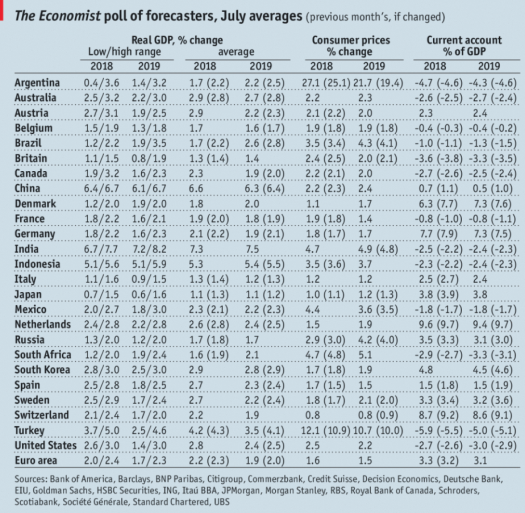

One of the main ways the Fed has won its credibility on inflation has been setting interest rates higher, sometimes much higher, than the inflation rate. This was most extreme in 1984, when short-term interest rates spent much of the year over 10 percent while consumer price inflation (stripping out food and energy) finished the year under 5 percent. When investors and savers can get a “free lunch” by earning a high inflation-adjusted return in Treasuries, they’re incentivized to do so rather than invest in new production or consuming goods and services, both of which would put upward pressure on inflation.

This is reasoning from a price change. Real rates were high in the mid-1980s precisely because growth was strong. And buying Treasuries is not an alternative to producing consumer and investment goods. That’s mixing up financial investment with physical investment. For instance, suppose America had a massive corporate investment boom financed by corporate bonds. Then you’d see lots of bond buying and lots of physical investment at the same time. They are not alternatives. A better argument would have been that Reagan’s fiscal deficits crowded out private investment.

But this has broader distortionary effects in the economy. On a global level, if investors can earn a high real interest rate on U.S. assets, they’re going to do so, which all else equal will drive the dollar higher in foreign exchange markets than it otherwise would be. The dollar being artificially higher will make U.S. exports less competitive in global markets, leading to larger trade deficits.

Distortionary? Artificial? Sorry, but Volcker and Greenspan were targeting inflation at about 4% from 1982-90. There was nothing “artificial” about the resulting interest rates, they were simply the result of market forces. The Fed does not set the real interest rate over an extended period of time. Again, the fiscal deficits might have played a role (although even that factor was probably less important than widely believed at the time.)

In other words, the Fed established its credibility on inflation over the past few decades by setting real interest rates at a high level, which helped to orient the economy around financial activities, consumption and imports rather than production, labor and exports.

These are not either/or scenarios. Consumption is not an alternative to production, labor etc. Consumption is an alternative to investment. Indeed consumption often booms during periods of high employment, such as the late 1960s and the late 1990s. The same is true of financial activities. And production is an alternative to leisure, not an alternative to consumption. And real interest rates have not in fact been high over the “past few decades”. They were high in the 1980s and have been low since 2001.

Trump wants a different model. It’s what his tariff threats seek to accomplish: making the U.S. economy more production-oriented rather than consumption-oriented. And he wants monetary policy to help do the same thing. If the Fed stops increasing interest rates over the next few quarters, then we’ll never get those high real interest rates in this economic cycle that we’ve gotten in past cycles. This should put downward pressure on the dollar, making U.S. exports more competitive, but at the cost of cheaper imports for U.S. consumers.

Where to begin? How does downward pressure on the dollar lead to cheaper imports for U.S. consumers? How does Trump’s tariff model lead to a more “production-oriented” economy? Are low tariff countries like Singapore, Switzerland and Germany not production-oriented? And how can monetary policy make the US more production-oriented? Isn’t money neutral in the long run? Where’s the long run aggregate supply curve in this model?

Update: Several commenters suggested I misinterpreted the phrase “at the cost of cheaper imports”. Perhaps it was meant to imply that imports would get more expensive. I.e., “at the cost of more expensive imports for consumers”.

In the long run, if trade and monetary policy leads the U.S. economy to be somewhat less consumption-oriented and more investment-oriented, that’s something we can handle.

How could monetary policy have any long run impact on the share of GDP going to investment? Is Sen arguing that monetary policy has a long run impact on real interest rates?

I guess in Bloomberg world, high interest rates lead to more manufacturing and exports, which hurts workers. Low interest rates lead to more production, which helps workers. But consumers must pay the “cost” of cheaper imports from the weaker dollar.

Am I missing something?

HT: Ramesh Ponnuru