How did we end up here?

I’ve finally had a chance to read Paul Romer’s critique of macroeconomics, and it’s every bit as interesting as you might expect. I’m going to focus on a single issue, which in my view lies at the heart of what’s gone wrong in recent decades—identification. This issue has been the main focus of my blogging over the past 7 1/2 years, so it’s very dear to my heart. By late 2008, it was clear to me that not only did economists not know how to identify monetary shocks, but also that they were very far off course, and didn’t even understand that fact. Indeed this misunderstanding actually became highly destructive to progress in both economic science and economic policymaking. One of the two the worst contractionary monetary shocks of my lifetime is generally regarded as “easy money”. So how did we get here?

1. The earliest monetary shocks were seen as involving the price of money. Coin debasement was a common example. No one knew the money supply, and banks did not yet exist. This policy tool was used by FDR in 1933, but today has fallen out of fashion in big economies. Small countries like Singapore still use the price of money (exchange rates) as a policy instrument, but they do not drive the research agenda. I’m trying to bring it back with NGDP futures targeting.

2. Although the monetarist approach to identification (i.e. the money supply) dates back at least to Hume, it really came into its own with fiat money, especially during hyperinflationary fiat regimes. Milton Friedman preferred the M2 money supply as a monetary indicator, at least during part of his career.

3. Then for some strange reason the profession shifted from the money supply to interest rates, as an indicator of monetary shocks. But why?

Perhaps you are thinking that you know the answer. Maybe it had something to do with the early 1980s, when velocity was unstable and monetarism was “discredited”. If that is indeed what you are thinking, then it merely illustrates that you are even more confused than you know. Yes, velocity is unstable. And yes, that means Friedman’s 4% money growth rule might not be a good idea. But that has absolutely no bearing on the argument for replacing the money supply with interest rates, as an indicator of the stance of monetary policy.

The relationship between i and NGDP is just as unstable as the relationship between M2 and NGDP, probably more unstable. At least with M2, we generally can assume that an increase means an easier monetary policy, and a reduction means a tighter policy. We don’t even know that much about the relationship between interest rates and NGDP. Right now, markets expect about a 1% fed funds rate in 2019. Suppose you had a crystal ball that told you that the fed funds rate in 2019 would be 3%, not 1%. There’s a classic “monetary shock”. The stance of monetary policy changed unexpectedly. But which way—is that easier than expected policy, or tighter? I have no idea, and you don’t know either. Even worse, my best guess would be “easier” but the official model says “tighter.”

Paul Romer says we know that monetary shocks are really important. I agree. And he says the Volcker disinflation proves that. I agree, and could cite many other examples, probably even more than Romer could cite. So I’m completely on board with his general critique of those who claim we don’t know whether monetary shocks are important. But Romer then claims that the real interest rate is a useful measure of the stance of monetary policy, and it isn’t—not even close.

Am I denying that if the Fed suddenly raised the real interest rate by 200 basis points, money would be tighter on that particular day or week? No, I agree that that statement is true. But it’s also true that if the Fed suddenly raised the nominal interest rate by 200 basis points, money would be tighter on that particular day or week. Or if the Fed suddenly cut M2 by 10%, money would be tighter on that particular day or week.

So why don’t we use M2 to measure the stance of monetary policy? Because over longer periods of time, movements in M2 do not reliably signal easier or tighter monetary policy. But that’s also true of movements in nominal interest rates. If you have a highly contractionary policy, then inflation and nominal rates will fall in the long run. Hence low rates don’t mean easy money. And this argument also applies to real interest rates. If the Fed adopts a tight money policy that drives the economy into a depression, then real interest rates will decline, even as policy is effectively contractionary. This actually happened in 1929-33 and 2008-09.

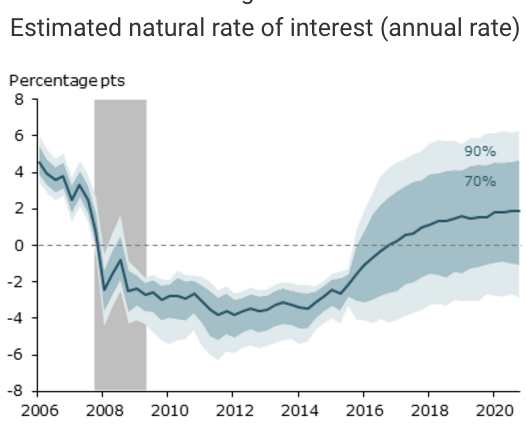

All of the traditional indicators are unreliable. The smarter New Keynesians will say that money is tight when the interest rate is above its Wicksellian equilibrium rate. But how do we know when that is the case? After all, the Wicksellian equilibrium rate cannot be directly observed. You need to look at outcomes; Wicksell said interest rates were above equilibrium when prices were falling, and vice versa. But that means we can only identify easy and tight money by looking at outcomes; are prices rising or falling?

Today we would substitute above or below 2% inflation, or 4% NGDP growth, but the basic idea is the same. Money is tight when it’s too tight to hit your target, and vice versa. Ben Bernanke got this right in 2003, and then lost track of this concept when he joined the Fed:

Do contemporary monetary policymakers provide the nominal stability recommended by Friedman? The answer to this question is not entirely straightforward. As I discussed earlier, for reasons of financial innovation and institutional change, the rate of money growth does not seem to be an adequate measure of the stance of monetary policy, and hence a stable monetary background for the economy cannot necessarily be identified with stable money growth. Nor are there other instruments of monetary policy whose behavior can be used unambiguously to judge this issue, as I have already noted. In particular, the fact that the Federal Reserve and other central banks actively manipulate their instrument interest rates is not necessarily inconsistent with their providing a stable monetary background, as that manipulation might be necessary to offset shocks that would otherwise endanger nominal stability.

Ultimately, it appears, one can check to see if an economy has a stable monetary background only by looking at macroeconomic indicators such as nominal GDP growth and inflation. On this criterion it appears that modern central bankers have taken Milton Friedman’s advice to heart.

Others will object that New Keynesians understand that it’s the level of interest rates relative to the Wicksellian equilibrium rate that matters. For instance, a recent paper by Vasco Curdia shows that money was actually quite contractionary, during and after the Great Recession.

Yes, but that paper was written in 2015. Back in late 2008 and throughout 2009, market monetarists were just about the only people claiming that monetary policy was highly contractionary—and that was the period when we most needed clear thinking. Others were lulled by meaningless indicators like low nominal and real interest rates, as well as a ballooning monetary base.

How did we end up using interest rates as an indicator of the stance of monetary policy? Romer provides one possible clue in his paper:

By rejecting any reliance on central authority, the members of a research field can coordinate their independent efforts only by maintaining an unwavering commitment to the pursuit of truth, established imperfectly, via the rough consensus that emerges from many independent assessments of publicly disclosed facts and logic; assessments that are made by people who honor clearly stated disagreement, who accept their own fallibility, and relish the chance to subvert any claim of authority, not to mention any claim of infallibility.

I fear that economists have deferred too much to the “central authority” of central banks. When I talk to macroeconomists, they seem to think it’s natural to use interest rates in their monetary models because the central banks actually target short-term interest rates. But that’s a lousy reason.

Another problem may be that some economists are infected by a popular prejudice—that low interest rates are a “good thing” for the economy. We visualize that we would be more likely to buy a new house if interest rates fell, and extrapolate from that to the claim that low rates would boost GDP. That’s obviously an example of the fallacy of composition. Yes, I’d be more inclined to borrow money if interest rates fell, ceteris paribus. But some other guy is less inclined to lend me the money if interest rates fell, ceteris paribus. Of course ceteris is not paribus if interest rates fall, and it all depends on whether they fall because of an increase in the money supply (expansionary) or more bearish expectations from the public (contractionary.)

Elsewhere I call this “reasoning from a price change”, and even Nobel laureates do it:

Real interest rates have turned negative in many countries, as inflation remains quiescent and economies overseas struggle.

Yet, these negative rates haven’t done much to inspire investment, and Nobel laureate economist Robert Shiller is perplexed as to why.

“If I can borrow at a negative interest rate, I ought to be able to do something with that,” he tells U.K. magazine MoneyWeek. “The government should be borrowing, it would seem, heavily and investing in anything that yields a positive return.”

But, “that isn’t happening anywhere,” Shiller notes. “No country has that. . . . Even the corporate sector, you might think, would be investing at a very high pitch. They’re not, so something is amiss.”

And what is that?

“I don’t have a complete story of why it is. It’s a puzzle of our time,” he maintains.

Actually there is no puzzle. Shiller seems unaware that it’s normal for the economy to be weak during periods of low interest rates, and strong during periods of high interest rates. He seems to assume the opposite. In fact, interest rates are usually low precisely during those periods when the investment schedule has shifted to the left. Shiller’s mistake would be like someone being puzzled that oil consumption was low during 2009 “despite” low oil prices.

I know what commenters will say—I’m a pigmy throwing stones at Great Men. They are right. Guilty as charged. Look, I’ve made the mistake of reasoning from a price change numerous times—it’s easy to do. But that won’t stop me from criticizing the ideas of people much more famous than I am. In Paul Romer I’ve found a kindred spirit.

PS. Since I’m nearly 6’4″, perhaps I should be PC and add, “Not that there’s anything wrong with being a pigmy”.

PPS. This link has videos to the recent Mercatus/Cato conference on monetary policy rules.