The following is related to my most recent essay at The Economist.

I suppose it’s presumptuous for me to pontificate on Bretton Woods II, given I found out the meaning of the term only a few weeks ago. But heh, that’s never stopped me before. Here’s Wikipedia:

Bretton Woods II was an informal designation for the system of currency relations which developed during the 2000s. As described by political economist Daniel Drezner, “Under this system, the U.S. is running massive current account deficits to be the source of export-led growth for other countries. To fund this deficit, central banks, particularly those on the Pacific Rim, are buying up dollars and dollar-denominated assets.”

Well at least I was aware of the phenomenon.

There’s been a lot of recent discussion of whether Bretton Woods II is about to fall apart, with this post by Tim Duy being perhaps the most authoritative:

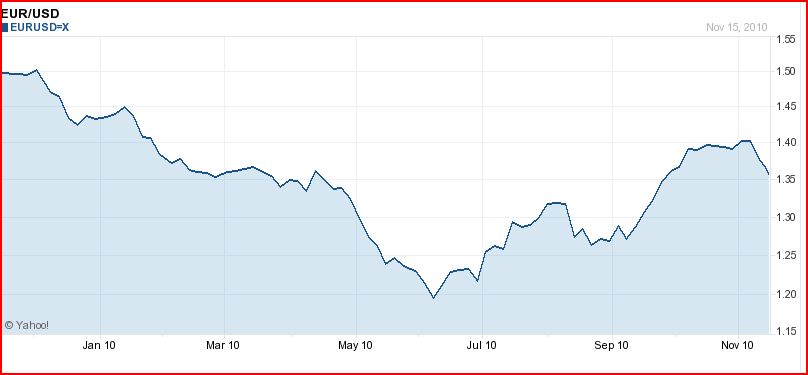

The inability of global leaders to address global current account imbalances now truly threatens global financial stability. Perhaps this was inevitable – the dollar has not depreciated to a degree commensurate with the financial crisis. Moreover, as the global economy stabilized the old imbalances made a comeback, sucking stimulus from the US economy and leaving US labor markets crippled. The latter prompts the US Federal Reserve to initiate a policy stance that will undoubtedly resonate throughout the globe. As a result we could now be standing witness to the final end of Bretton Woods 2. And a bloody end it may be.

I don’t know whether Bretton Woods II is about to collapse or not. But I am skeptical of much of the discussion of global imbalances, which in my view focuses far too much on currency/trade questions, and far too little on savings/investment imbalances. Before considering Duy’s views, I’d first like to address an argument recently made by Michael Pettis:

For that reason I am always puzzled by people who say that devaluing the dollar will have no impact on the US trade deficit because the problem is low savings relative to investment. No, that is not the problem. That is simply one of the definitions of a current account deficit. But if the dollar devalues, and consumer prices rise, US consumption is likely to decline. In addition, to the extent that any of the stuff Americans used to import before the devaluation is now produced domestically (not all, but any), then US production must rise. Since savings is equal to production minus consumption, the US savings rate must automatically rise.

As you may know, I’ve never liked arguments that “reason from a price change”:

1. Next year the price of oil will be higher, therefore we can expect consumers to . . .

2. Interest rates will fall therefore we can expect investment to . . .

3. The dollar will fall therefore we can expect exports to . . .

This is often a misuse of basic supply and demand theory. There is no necessary correlation between a price change and a quantity change; it entirely depends on why the price changed. Was it more supply, or more demand? Now that doesn’t mean Pettis is wrong here, he probably assumed a particular cause of the price change in the back of his mind. But we need to start with that fundamental cause.

Often when people talk about the need for the US to devalue the dollar, they imagine it occurring through an expansionary monetary policy. But monetary policy doesn’t have real effects in the long run, so it can’t solve secular problems. There is no particular reason to expect that having the Fed devalue the dollar would “improve” the US trade balance:

1. In the long run money is neutral; hence the real exchange rate is unaffected.

2. In the short run the trade balance might get worse due to the J-curve effect.

3. If monetary stimulus has a business cycle effect, then the trade balance might get worse if the stimulus creates a boom in the US.

So while Pettis might be right, I don’t have much confidence that the sort of dollar depreciation people are currently discussing would materially affect the US trade balance. The most “beggar-thy-neighbor” policy in American history was probably the massive devaluation of 1933, and the trade deficit initially got worse.

Of course it may be the case that a country adjusts its currency value by altering the savings/investment equation. For instance, many people are calling on China to revalue it’s yuan by purchasing fewer foreign bonds. That doesn’t necessarily reduce Chinese saving (it depends what else the Chinese government does) but there are certainly scenarios where it might.

On the other hand I don’t have much confidence that a laissez-faire attitude in China would materially affect the US trade balance in the long run. Remember that if China removed all currency controls, it would also be much easier for Chinese citizens to invest overseas. I think we need to see China in a broader East Asian context. One reason I could foresee Bretton Woods II being around for a long time is that East Asia is very different from the West, and those differences will become much more important over time, as East Asian wealth skyrockets. (The term “skyrocket” is not hyperbole, Chinese wealth is set to rise dramatically.) All of East Asia seems to be moving toward ultra-low birth rates and economies that are structured to produce high saving rates. I don’t know if Singapore intervenes to weaken their currency, but given the extraordinary high savings rates there you’d expect a big CA surplus even if the government wasn’t accumulating foreign reserves. The exact same thing occurs if the Singapore public buys the assets, and puts them in retirement accounts.

Over the next few decades China will get much richer. As it does so, I’d expect its economy to resemble other East Asian countries more than the US. And that will be true even if their government ends its weak yuan policy. To take just one trivial example, I’d expect far more Chinese citizens to be speculating in property in LA, Vancouver and Sydney, than Westerners buying vacation homes in Shanghai or Hainan.

The East Asian economy is set to become extremely large in 20 or 30 years. Given the enormous structural differences from our economy, I think it quite likely that the imbalances will become even larger in absolute terms. When I lived in Australia in 1991, many Aussies were worried that their huge CA deficits were unsustainable, and also the cause of their recession. They haven’t had a recession since, and they have continued to run very large deficits. I see no reason why this “unsustainable” trend cannot continue for many more decades.

This is not to suggest that I disagree with Pettis’ policy recommendations, indeed I think his views on restructuring the Chinese economy make a lot of sense. He also seems to share my view that while moderate yuan appreciation would be desirable, a sudden and sharp appreciation might be counterproductive:

This is why I worry that we are putting too much pressure on the renminbi. There are many ways for China to rebalance, and they all involve the same process of transferring income from producers to households. Raising the value of the renminbi, for example, increases the real value of household income in China by reducing the cost of imports.

It balances this by lowering the profitability of exporters. The net result is that if it is done carefully, the household income share of China’s GDP rises when the renminbi is revalued, and with it consumption rises too. Since China must export the difference between what it produces and what it consumes or invests, raising the value of the currency also reduces China’s trade surplus.

But what would happen if China were to raise the currency too quickly? In that case the profitability of the export sector would decline so quickly that exporters would be forced either into bankruptcy or into moving their facilities abroad to lower-wage countries. Either way, they would have to fire local workers.

Tim Duy also seems skeptical of those who put all the focus on Chinese surpluses:

But I don’t want to make this piece about China. It is more than China at this point. It became more than China the instant US Federal Reserve policymakers woke up one morning and decided they needed to take the dual mandate seriously. And seriously means quantitative easing. Brad DeLong suggests that when the Fed actually acts on November 3, it will be too little too late. But if it is too little, more will be forthcoming.

Put simply, the Federal Reserve is positioned to declare war on Bretton Woods 2. November 3, 2010. Mark it on your calendars.

So perhaps Bretton Woods does not end because foreign governments are unwilling to bear ever increasing levels of currency and interest rate risk or due to the collapse of private intermediaries in the US, but because it has delivered the threat of deflation to the US, and that provokes a substantial response from the Federal Reserve. A side effect of the next round of quantitative easing is an attack on the strong dollar policy.

Even if we could boost US demand by bashing China (and I doubt we could) there is a much better way; boost NGDP with a more expansionary monetary policy. Where I differ with Duy is that I don’t think it will permanently end Bretton Woods II. Yes, there may be some short term reduction in imbalances, but once the US recovers I have trouble seeing why we would not revert to running large deficits. In my view there are only two permanent ways to address the US CA deficit; raise the US saving rate through fiscal reforms, or depress investment by adopting demand and supply-side policies that impoverish the country. I think you know which approach I prefer.

BTW, David Beckworth posted on this earlier, and he shares my skepticism about the end of BWII. Bill Woolsey also has a good post on exchange rates.

HT: Marcus Nunes