Fed dual mandate watch

I’m thinking of adding a monthly feature to keep track of how the Fed is doing in terms of fulfilling its dual mandate. Recall that the Fed tries to keep inflation close to 2.0% and unemployment close to about 5.6% (the Fed’s current estimate of the natural rate.) One implication of the dual mandate is that they should try to generate above 2% inflation during periods of high unemployment, and below 2% during periods of low unemployment.

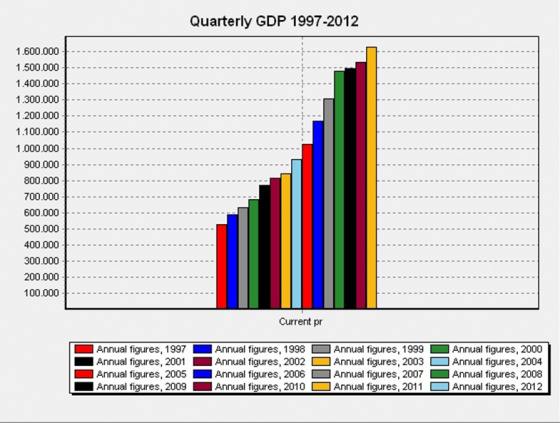

In July 2008 unemployment rose above 5.6%, and it’s averaged nearly 9% over the past 46 months. So the Fed’s mandate calls for slightly higher than 2% inflation during this 46 month slump. Last month I reported that the headline CPI had risen 4.6% in the 45 months since July 2008. Now we have the May data, and the headline CPI has gone up 4.3% in the 46 months since July 2008. So the annual inflation rate over that nearly 4 year period has fallen from a bit over 1.2%, to 1.1%. BTW, NGDP growth has been the lowest since Herbert Hoover was in office. Epic fail.

Some might argue; “Yes, the Fed’s fallen short, but no one can dispute that they’ve tried hard, they’ve run an extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy.”

They would be wrong. That’s partly because Bernanke continually insists the Fed can do much more, but that the economy currently doesn’t need any more stimulus. But the bigger problem is that money hasn’t been accommodative.

Here’s what Bernanke said in 2003:

The only aspect of Friedman’s 1970 framework that does not fit entirely with the current conventional wisdom is the monetarists’ use of money growth as the primary indicator or measure of the stance of monetary policy. . . .

The imperfect reliability of money growth as an indicator of monetary policy is unfortunate, because we don’t really have anything satisfactory to replace it. As emphasized by Friedman . . . nominal interest rates are not good indicators of the stance of policy, as a high nominal interest rate can indicate either monetary tightness or ease, depending on the state of inflation expectations. Indeed, confusing low nominal interest rates with monetary ease was the source of major problems in the 1930s, and it has perhaps been a problem in Japan in recent years as well. The real short-term interest rate, another candidate measure of policy stance, is also imperfect, because it mixes monetary and real influences . . .

The absence of a clear and straightforward measure of monetary ease or tightness is a major problem in practice. How can we know, for example, whether policy is “neutral” or excessively “activist”? I will return to this issue shortly. . . .

Ultimately, it appears, one can check to see if an economy has a stable monetary background only by looking at macroeconomic indicators such as nominal GDP growth and inflation. On this criterion it appears that modern central bankers have taken Milton Friedman’s advice to heart.

When I started blogging I was the only person claiming Fed policy was actually very tight. As far as I recall even the other market monetarists were not making that claim. Even today, almost no highly respected economist will call Fed policy “tight.” The press almost universally calls it “accommodative.” Ben Bernanke himself calls it extraordinarily accommodative. Yet none of that is true. In 2003 Bernanke accurately described the difference between easy and tight money. It’s a pity that even today virtually all of our elite macroeconomists (on both the left and the right) don’t understand how to recognize the stance of monetary policy.

Until we see the nature of the problem, what hope do we have in solving it?

PS. Why do I keep repeating myself ad nauseum? Because other economists won’t accept that I am right, nor will they tell me why I am wrong.