Does unemployment actually lag output?

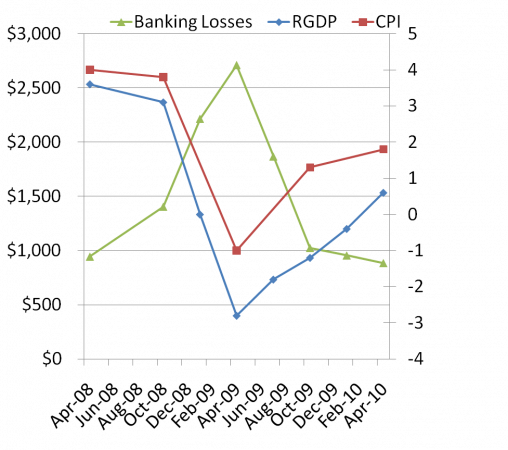

Everyone seems to think it does, so naturally I’ll argue the other side. What surprised me is how easy it is to make the argument. As you look at the following data, ask yourself what you’d expect to happen to unemployment if there were no lags. Keep in mind that the trend rate of RGDP growth is around 3%:

2008:1 and 2008:2 — RGDP falls at about 0.1%

2008:3 through 2009:2 — RGDP plunges 4.1%

2009:3 — RGDP rises at a rate of only 1.6%

2009:4 and 2010:1 — RGDP rises at a 4.35% rate

2010:2 and 2010:3 — RGDP rises at only a 2.15% rate

I’d expect unemployment to rise modestly in early 2008, soar in late 2008 and early 2009, rise a bit more in the 3rd quarter of 09, fall in late 2009 and early 2010, and then rise a bit in the summer of 2010. Here are the actual unemployment rates:

December 2007 (cyclical peak) — 5.0%

July 2008 — 5.8%

July 2009 — 9.5%

October 2009 (unemployment peak) — 10.1%

May 2010 (euro crisis begins) — 9.6%

November 2010 — 9.8%

Too early to know where it goes next, but I expect RGDP growth to pick up over the next few quarters, and unemployment to trend downward (although the recent 9.4% figure may have been a blip. But in general isn’t that exactly the unemployment pattern you’d expect if there was no time lag at all between output and the unemployment rate?

I think the problem here is that during the last three recessions unemployment has not fallen significantly during the early stages of recovery. One explanation for that raises no problems; growth has been slow. The last rapid recovery we saw was in 1983, and unemployment fell almost immediately from the moment the economy started recovering. The other issue is more complicated, productivity growth seems unusually high during recent recoveries. Still I think it is possible to overdo this difference. This table shows that while productivity during recent recessions has been much stronger than 1974 and 1982, there were also some fairly strong productivity numbers in garden variety recessions like 1957-58 and 1948-49.

Perhaps productivity growth was a bit higher in the early stages of recent recoveries for reasons unrelated to AD. In that case the baseline job growth might be a bit lower, but even so any extra AD would show up as more jobs. That could explain the close correlation in timing for the high frequency fluctuations in output and jobs discussed above, and the disappointing overall job growth. And I still insist that this recovery is fairly weak in terms of both real and nominal GDP

Tyler Cowen has a slightly different view:

The AD-only theories, taken alone, encounter major and indeed worsening problems with the data. Year-to-year, industrial output is up almost six percent, sales up more than six percent, but the labor market has barely improved. How does that square with the AD-only hypothesis? Has it been seriously addressed?

I think he is misreading the recent data on output. Elsewhere in his post he cites productivity data showing very strong gains in 2009. But the past 4 quarters only show 2.65% productivity growth. If productivity growth is not high, and jobs aren’t being created, how can I explain the rapid output growth observed by Tyler? I’d like to stick my head in the sand and deny it, but I guess that won’t do. Seriously, I think the problem is that the industrial production data is not representative. RGDP growth over the past 4 quarters in 3.25%. That’s not horrible, but on the other hand it’s not that much above trend. And unemployment has fallen a bit since the 10.1% peak of October 2009. He’s got a point about productivity being somewhat unusual in this recession, especially 2009; but the 6% industrial production figure may overstate things. Productivity gains in manufacturing tend to be much higher than in services, so even 6% manufacturing growth could coexist with both 2.65% overall productivity gains and also a relatively small gain in total jobs.

My previous critique of Tyler Cowen’s ZMP post was focused on one issue; I didn’t think the data supported his argument. After reading his recent post, I don’t want to argue against the general idea that there may be some workers who (in the short run) have MPs much lower than the wage rate. Some of the quarterly observations he discusses are very suggestive. And I don’t have a good feel for this issue, indeed I may have read too much into his earlier post. Tyler Cowen points out that Krugman once offered a similar hypothesis, and now rejects it out of hand, so I think Krugman may have also misread Tyler.

In earlier posts I argued that the sticky wage theory is often misunderstood. If the Fed suddenly imposes 10% fall in NGDP, it is not true that factory workers can keep their jobs by accepting 10% wage cuts. Why not? Because other workers may not. Suppose half of workers take 10% pay cuts (factory workers, etc) and half do not (teachers, health care workers, public employees, etc.) The aggregate wage will fall 5% and we’ll have a severe recession. During recessions people cut back on car purchases much more than health care (often paid for by insurance or Medicare), so it will be the factory workers losing their jobs, despite their willingness to take pay cuts. Now see if that argument reminds you of Tyler Cowen’s point 7:

What does the zero MP hypothesis add? First, the zero MP hypothesis explains why wage adjustments can’t do the trick for a lot of the unemployed, as wages won’t fall below zero. Second, the zero MP hypothesis explains why you need steady real growth, boosting the entire chain of demand, to reemploy lots of workers and reflation alone won’t do the trick. (I still, by the way, favor reflation because I think it will do some good.) Those predictions are not looking terrible these days.

I agree the “entire chain” may need a boost, but I think reflation can do the trick. On the other hand if we can’t get more people to buy cars, wage cuts for windshield makers in Toledo are not going to restore their jobs.

I completely agree with the following by Arnold Kling:

I want to reiterate that I would like to see the Fed behave as if this were an AD-caused recession. However, we should be prepared for the possibility that it is not, in which case expansionary policies will cause price bubbles in some sectors without doing much for employment and output.

What would get me to give up my AD-only explanation (actually 80% AD and 20% AS)? Evidence that more NGDP would not result almost one for one in more RGDP. How could we discover who’s right? It would be simple—just create NGDP and inflation (or NGDP and RGDP) futures markets, and watch how they react to monetary shocks. How do we identify monetary shocks? Look for major Fed announcements, and see if the press interpretation is confirmed by market responses. Example: Bernanke gives a speech strongly hinting at QE3. The dollar plunges and stocks soar. That’s a good indication the speech increased the expected future monetary stimulus. To see how much of the recession is real and how much is demand-side we’d merely have to watch the reactions in the NGDP and inflation markets. I say NGDP expectations would rise much more than inflation expectations.

This would be incredibly useful information to policymakers, and it would cost peanuts for the US government to set up and subsidize trading in such a market. Why don’t they? My wholesome and naive personality says they are well-intentioned, and just don’t know about my ideas. Many would argue that Robin Hanson has a more clear-eyed and realistic take on what makes people tick.

What do you guys think? Do elite macroeconomists and Fed officials enjoy presiding like high priests over a mysterious macroeconomy, or do they actually want to discover the truth?

PS. One reason I hold my views so strongly is that even though we don’t have a NGDP futures markets, we do have enough reasonable proxies that I am pretty sure monetary stimulus “works.”