Will we have high inflation in the 2020s?

Probably not, at least if the Fed sticks to its 2% AIT. But I’m not reassured by the arguments being offered:

Actually, things like globalization and a lack of COLAs don’t matter it all. It mostly boils down to NGDP growth (a variable that globalization and COLAs do not significantly impact.)

If we have fast NGDP growth during the 2020s, say 5% or more, then we’ll likely have high inflation. If we hold NGDP growth below 4% then we’ll have moderate inflation. Below 3% and we’ll fall short of the Fed’s target. (These are decade average claims; 2020-22 will be unusual.)

It’s all about monetary policy. When it comes to inflation, fiscal policy doesn’t matter. Globalization doesn’t matter. Unions and minimum wage laws don’t matter. It’s completely up to the Fed.

Are they going to give us roughly 2% inflation on average, as they promised, or are they a bunch of liars? I trust them, but will “verify”.

PS. Off topic, I highly recommend Razib Khan’s new post on Italian history, which is comparable to his masterful posts on Indian history. If he did a half dozen more such posts, then turned them into a book, it would be one of the best books of 2022.

PPS. Give Business Insider credit for this prescient March 6, 2020 article.

Tags:

8. March 2021 at 14:16

> If we have fast NGDP growth during the 2020s, say 5% or more, then we’ll likely have high inflation. If we hold NGDP growth below 4% then we’ll have moderate inflation. Below 3% and we’ll fall short of the Fed’s target. (These are decade average claims; 2020-22 will be unusual.)

This makes it sound like you think we’ll have 3% RGDP growth regardless of what else happens. Why would that be true? Can’t the Fed hurt RGDP if they screw up? Doesn’t globalization help RGDP?

8. March 2021 at 15:12

Oscar, Globalization has an effect on growth, but it’s tiny. I expect about 1.5% to 2% RGDP growth on average.

Bad monetary policy affects growth in the short run, but doesn’t have much long run effect.

8. March 2021 at 15:14

“It’s all about monetary policy.”

Now more than ever. The danger lies in the Fed language of unemployment/inflation.

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/debating-monetary-policy

8. March 2021 at 16:01

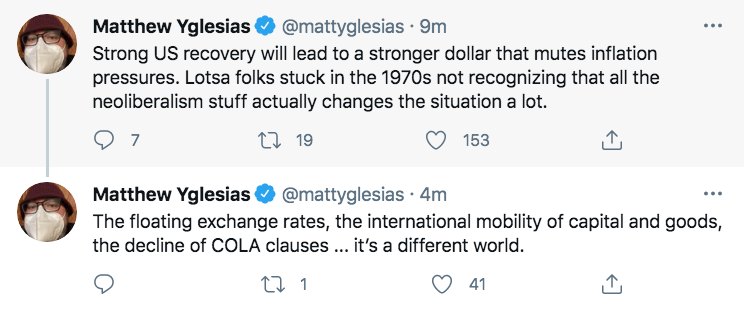

I read Matt a lot during the Great Recession. Either I’m not remembering what he used to write, or he’s forgotten a few of the lessons from that time period.

8. March 2021 at 17:10

Obviously hypothetical, but what happens in the following scenario?

Central bank targets 2% inflation AND federal govt decides it wants to target 5% inflation and will send coins (via the “trillion dollar coin” loophole) to people until it is achieved. Both the Fed and govt are watching the same future inflation indicator.

8. March 2021 at 19:18

Do changes in savings preferences and the velocity of money matter to how likely the Fed is to meet its AIT of 2%? I don’t view the Fed as a very nimble institution. I would not be surprised if the savings rate of the US rises for a few years, landing at an unpredictable place. At the very least it would make sense (from a psychological perspective) for Americans to save more to ride out potential disasters. But how much more will they save, and how much warning will the Fed have before expansion of the money supply starts shifting more towards boosting NGDP growth than boosting savings?

People seeing high risk for inflation have very little trust in the competence of the Fed. On the other hand, it seems like people seeing little risk of high inflation place too much trust that Fed competence isn’t necessary.

8. March 2021 at 19:21

Scott Said:

“It’s all about monetary policy. When it comes to inflation, fiscal policy doesn’t matter.”

This does not seem right to me. If the federal government spends like crazy ($1.9 Trillion!!) does this cause the fed to change monetary policy? If it does, then is it not the case that fiscal policy changed monetary policy and thus influenced inflation?

8. March 2021 at 19:56

Effem, I hope the Fed offsets the effect, but who knows what they’d do. It’s academic, as there won’t be a trillion dollar coin.

Lizard, You asked:

“Do changes in savings preferences and the velocity of money matter to how likely the Fed is to meet its AIT of 2%?”

Probably not, unless it is very rapid and extreme. But not over the entire 2020s.

Bob, You asked:

“If the federal government spends like crazy ($1.9 Trillion!!) does this cause the fed to change monetary policy?”

The Fed is legally obligated to maintain stable prices. Let’s hope they don’t break the law.

8. March 2021 at 23:15

A lot of people seem to think that 1970s inflation was solely caused by the oil crisis and that a strong dollar will mute this going forward. Sigh.

8. March 2021 at 23:32

We seem to live in an era where one can make significant intellectual contributions just by restating forgotten lessons from a few decades ago, in this case that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. Also, aggregate demand is whatever Alan Greenspan (or his current successor) wants it to be.

9. March 2021 at 00:39

“Monetarist theory, which came to dominate economic thinking in the 1980s and the decades that followed, holds that rapid money supply growth is the cause of inflation. The theory, however, fails an actual test of the available evidence. In our review of 47 countries, generally from 1960 forward, we found that more often than not high inflation does not follow rapid money supply growth, and in contrast to this, high inflation has occurred frequently when it has not been preceded by rapid money supply growth.“

https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/rapid-money-supply-growth-does-not-cause-inflation

9. March 2021 at 00:46

M2 has grown by an unprecedented 25% year over year (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=BMRb). This has been offset by (or was done to offset) a similarly dramatic reduction in velocity.

What happens if, once the COVID-19 vaccination is complete, everyone goes on a spending spree and velocity sharply increases? Is one year of double-digit inflation unavoidable, or does the Fed have tools to rein that in? Or is it unlikely that velocity will quickly return to 2019 levels?

9. March 2021 at 04:29

I think we should keep some Sumnerian points in mind when considering the prospects of high inflation.

1. Listen to markets. Markets are very clear, in that, even rising inflation expectations beyond a point bring expectations of net disinflation, due to the expected reaction function of the Fed. We see this clearly lately, when nominal interest rates spike, but stock and gold prices fall, as the dollar index strengthens.

2. Average inflation targeting is, at best, merely somewhat less disinflationary than inflation targeting, when there’s a negative real shock. Hence, there’s still a disinflationary bias, on average.

3. The Fed has never engineered a soft landing. Maybe this time will be different, but the Fed must prove it to me.

9. March 2021 at 04:35

On a separate point, I think it’s worth pointing out that recent market reactions seem to indicate Fed offset of fiscal stimulus, in real time. This is not all bad though, as it’s may help take us further away from the ZLB, where the Fed may still struggle with policy, though it’s certainly an expensive and vastly suboptimal way of doing so.

9. March 2021 at 06:14

I am sure Scott is aware of this. But the mainstream financial press could not disagree with him more. In fact, I am pretty sure his views are not merely disagreed with, they are unaware his view even exists. I probably exaggerate a bit—but not by much. In my opinion Scott has been far more accurate than what others say about potential inflation. Market expectations are more in line with Scott as well (forward break even inflation rates). Again, I am sure I exaggerate—-although maybe not——but I could swear I have never read the term “monetary offset” in the financial press.

9. March 2021 at 06:29

Scott, to be more precise: fiscal policy doesn’t matter for the observed inflation rate.

But fiscal policy will have a big impact on what offsetting action the Fed needs to take to hit its target.

Large fiscal action will be bad for observed RGDP, assuming that the government isn’t as good at generating growth as private economic activity would have.

9. March 2021 at 10:43

Tacticus, Yes, despite the fact that RGDP grew 3%/year during 1972-81 and NGDP grew 11%/year, they think it was an adverse supply shock.

Brandon, The Fed has the tools.

Matthias, Yes, but only in the long run.

9. March 2021 at 10:57

“Trying to Learn. In my research on the Depression I found five New Deal wage shocks. Each one slowed the recovery.”

Might this be a good thing? I’m assuming the wage shocks were regulation/policy that led to higher pay for workers. By “slow the recovery”, I assume you’re referring to NGDP. But might less GDP with more pay for workers (which should mean less income for producers) be a good thing, given producers tend to have higher incomes and diminishing marginal utility? Still not sure I’m following the logic, but I think you’re coming from the POV that higher GDP is the sole goal.

10. March 2021 at 08:00

Natural resource constraints are more likely to impact upcoming inflation as the present release of the 4% February CPI just demonstrated (the monetary validation of OPEC’s administrated oil price increase).

The Keynesian economists have achieved their debauched objective, that there is no difference between money products and savings’ products. One increases the money stock (money products), while the other decreases the velocity of circulation (savings’ products).

One addresses the stabilization of Treasury issuance, and the long-term mortgage markets, the other bluntly benchmarks the output gap (production possible at maximum economic capacity, viz., the error-correction policy, the probable sustainability of its overshoot policy in N-gDp level targeting).

Right now the monetary flows’ sweet spot for an injection of money products (1.9 trillion fiscal relief) is at its optimum.

10. March 2021 at 08:40

“When it comes to inflation, fiscal policy doesn’t matter.”

How can that be? You mentioned a few posts ago that there are four ways we can deal with our debt(or at least you quoted Reis as listing the four ways and didn’t seem to take exception):

1. issue more of it

2. default on it

3. create fiscal surpluses

4. inflate it away.

If 3 and 4 they are alternate solutions to a real problem we face, how do they not affect each other? I think we can dismiss option 1 since it’s just a can-kicking exercise. Given that, it seems to me reckless fiscal policy forces us into a choice between inflation and default?

10. March 2021 at 08:50

Trying, Not the sole goal, but a pretty important goal during the Great Depression.

Carl, If the debt got bad enough then inflation might be a realistic option. We are no where near that point. I was talking about the 2020s.

10. March 2021 at 09:07

Inflation numbers came out today–as expected—-fear of tightening declines. Why would he tighten? You keep being “right”.

10. March 2021 at 09:24

The U.S. $’s exchange rate will be N-gDp’s casualty. All bank-held savings are impounded and ensconced in the payment’s system. Banks do not loan out existing deposits period.

A suppressed or even negative yield curve, an excess of savings over real-investment outlets (and associated mal-investment), stems from the fact that adding infinite money products (QE-Forever), decreases the real-rate of interest ( – R *), and has a negative economic multiplier.

Whereas the activation and discharge of monetary savings, $15 trillion in commercial bank-held savings (income not spent), of finite savings products (near money substitutes), increases the real-rate of interest (+ R *), produces higher and firmer nominal rates, and has a positive economic multiplier.

10. March 2021 at 09:37

As my favorite poet said: “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

https://alhambrapartners.com/2021/03/08/standard-textbook-dollar-or-eurodollar-standard/

“In the US, Ben Bernanke was talking about tapering QE because economic fundamentals appeared to be improving rapidly (the unemployment rate most of all).”

10. March 2021 at 17:44

As a Slow Boring subscriber I’m a bit sad that Matt doesn’t read your blog, or at least isn’t more familiar with your work and posts like this. Will link to it when there are future posts on inflation there.

Also, the Razib Khan recommendations are piling up. I saw that post was paywalled and queued 2 other posts of his to see if it was worth the time to become a regular reader and it sounds like it likely is.

11. March 2021 at 07:01

Sheila Bair:

The July 2011 demarcation in E-$ liabilities was principally due to: (1) “the FDIC formally modified the assessment base in 2011 to include all bank liabilities”, which made foreign deposits, e.g., E-$ borrowings, more expensive (never before applied assessment fees), and Basel’s additive Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR).

As E-$s were being destroyed, the U.S. $ rose in sympathy.

https://alhambrapartners.com/2021/03/10/what-must-lie-beyond-the-ms/

I.e., the E-$ market was once bigger than the domestic money supply market. The absolute decline has stymied relative inflation.

11. March 2021 at 10:09

Can Sar, He has fewer posts than Yglesias, but they are very high quality.

12. March 2021 at 07:33

As Dr. Philip George says: when interest rates go up, flows into savings accounts increase.

The sterilization of commercial bank savings deposits generates low inflation. Banks don’t loan out deposits. Deposits are the result of lending/investing. So, velocity inevitably falls. Such is the sole cause of secular stagnation.

Historical FDIC’s insurance coverage deposit account limits (commercial banks):

• 1934 – $2,500

• 1935 – $5,000

• 1950 – $10,000

• 1966 – $15,000

• 1969 – $20,000

• 1974 – $40,000

• 1980 – $100,000 (velocity begins to fall)

• 2008 – $unlimited

• 2013 – $250,000 (caused taper tantrum)

12. March 2021 at 07:37

The fallacious ideas are vitiated on the largely false premises on which deregulation, laissez-faire economics is based (“abstention by governments from interfering in the workings of the free market”), viz., that demand deposits shifted into savings deposits in commercial banks constitute the “savings’ of the depositors, that these are “lent” to the banks, and that the commercial banks are only a “medium” through which this end is affected.