Why macro matters

I feel like a lazy bum. This morning Ben Bernanke created $250,000,000,000 in new wealth before I’d even finished breakfast. That’s right, his speech led to about a 1/2% pop in equity prices. Given world markets seem to respond to Fed easing by about as much as US markets, that’s a half percent of roughly $50,000,000,000,000 (aka 50 trillion.)

And don’t say all the gains melted away by lunchtime. That’s not how equity markets work. Sure the disappointing consumer data depressed prices a few hours later, but they remain 1/2% above the level they would have been without that easing.

Bernanke didn’t actually say too much new, but he was pretty definitive. It seems we will get QE, and no change in the 2% inflation target. That might be viewed as disappointing. But the speech itself was fairly dovish (or pro-growth.) Indeed Bernanke staked out an almost Svenssonian position:

1. He clearly stated that inflation could be too low.

2. He strongly implied 2% is the right number.

3. He suggested that current forecasts are for well below 2% inflation.

4. He said that’s not good enough, policy needs to be more expansionary if inflation is expected to be too low at a time of 9.6% unemployment.

5. The Fed needed to do something about this situation.

I think Bernanke’s gamble is that 2% inflation will be enough, as long as they go all out for that figure. Using intro macro, Bernanke’s suggesting that the SRAS curve is now so flat that even getting up to 2% inflation would require much faster RGDP growth. He considered the initial recovery to be “reasonably strong.” I disagree, but if that’s his definition of fairly strong, then yes, 2% inflation would probably generate enough growth to satisfy Fed moderates like Bernanke.

The title of this post has a double meaning. I’m going to argue that monetary policy is really, really important at the zero bound. And in section 2 I’ll argue that monetary economics talk is also really, really important . (I know . . . how self-serving for a monetary economics blogger.)

Part 1. Why policy is important: Unless you want to be a complete ostrich, I don’t see how anyone could seriously deny that over the past 6 weeks the world equity markets have been repeatedly reacting to a long string of Fed statements and press releases. Yes, I know that the financial press cannot always be relied upon when they speculate as to what caused stocks to rise. But if anyone looks at this issue seriously, and with an open mind, I can’t see how they can fail to see the highly persuasive evidence that Fed announcements strongly affect equity markets. As just one example, the Dow occasionally soars or plummets by several hundred points immediately after a 2:15pm Fed target rate announcement.

To me, this suggests we shouldn’t even be arguing anymore about “pushing on a string.” Equity markets are up by 10% to 20% over the last 6 weeks (in both nominal and real terms), that’s a very important effect regardless of whether traders are operating with a faulty model or not. I can’t imagine how Chicago-type economists can go on about how swapping one zero-interest asset for another does nothing. Surely an extra $5 trillion in real wealth is something. They need to stop paying attention to their models, and look at what the markets are saying.

As for Mr. Krugman, his own model says swapping one zero interest asset for another is highly effective, if the action is expected to be permanent. (If temporary, it isn’t effective whether interest rates are at the zero bound or not.) Yet Krugman consistently pooh-poohs the prospects for conventional OMOs. I’m reminded of the stories that people like Richard Kahn had to keep reminding Keynes what he was trying to say in the General Theory.

In my view the whole pushing on a string debate is over. Case closed. If people want to close their eyes to how the markets are reacting to hints of Fed easing, that’s their prerogative. Of course some will argue that it is higher inflation expectations that are doing the job. But any permanent QE will create higher inflation expectations; that’s the whole point. And we’ve always known that temporary QE doesn’t do anything. So what’s the debate all about?

Part 2: Why monetary pundits matter: In my view $5 trillion is a reasonable estimate of the amount world stock markets have increased as a result of Fed talk about easing policy since the beginning of September. That’s 10% of my crude estimate of total world stock market equity. The exact number isn’t important, just the order of magnitude; $3 trillion or $7 would have the same qualitative implications. And the total gains to society have probably been far greater, as monetary stimulus also helps workers, not just capitalists. (Of course it’s a zero-sum game for bond markets.)

So who is responsible for all this wealth creation? Surely some credit must go to the Fed, after all, they are the institution that is ultimately responsible for determining monetary policy. But I think others also deserve some credit. Back in August, before all this occurred, Paul Krugman made the following observation:

So why am I even slightly encouraged? Because the critics did, at least, succeed in moving the focal point. Not long ago gradual Fed tightening was the default strategy; but as I said, at this point the Fed realized that continuing on that path would have unleashed both a firestorm of criticism and a severe negative reaction in the markets.

What we need to do now is keep up the pressure, so that at the next FOMC meeting the members are once again confronted by the reality that not changing course would be seen as dereliction of duty. And so on, from meeting to meeting, until the Fed actually does what it should.

I know: it’s a heck of a way to make policy. In a better world, the Fed would look at the state of the economy and do what was right, not the minimum necessary. But wishing for that kind of world is like wishing that Ben Bernanke were running the place.

Pretty prophetic eh? No wonder Brad DeLong is always saying Krugman’s right about everything. I agree, the Fed (like the Supreme Court) clearly does respond at least somewhat to outside pressure. So how much credit do we pundits deserve for this stock rally? Let’s take a conservative figure, assume it’s 10% due to outside pressure and 90% from the Fed seeing the light without any outside influence. So the pundits created a mere $500 billion in stock wealth since September 1st. Of course I’d like to take some credit for all this, especially since the Fed mentioned NGDP targeting in its most recent minutes. But in all honesty I think the markets reacted to level targeting of prices, not NGDP. I’ve also pushed level targeting, but Woodford and Eggertsson probably deserve most of the credit. So of the total of $500 billion in new wealth created by pundits pushing for easy money, let’s give Woodford and Eggertsson each 10%. Perhaps uber-pundit Paul Krugman deserves 5%, and for all us small fry pushing for monetary stimulus I’ll assign a trivial 1% share. And recall that’s only 1% of the 10% share assigned to all pundits–1/1000 of the total.

In other words, we at TheMoneyIllusion deserve credit for a mere $5 billion dollars in wealth creation. And I say “we” because it’s a collaborative project. For instance commenter Marcus Nunes sent me the old Bernanke papers from 1998 and 2003, in which he told Japan to do all the things that we are now telling the Fed to do. After I posted long excerpts, lots of other bloggers and media outlets started picking up on the story. Don’t think that Bernanke isn’t aware of what he told the Japanese to do, and don’t think he isn’t aware of all the media outlets quoting those comments. So I figure Nunes deserves about a billion. Notice how these tiny crumbs, $5 billion, $1 billion, roughly correspond to the wealth of Facebook’s two founders.

Am I serious? I’m not quite sure. It all sounds as ridiculous to me as it must to you. On the other hand, Krugman’s argument sounds pretty reasonable to me, so I can’t see any good reason why it might not be true. The bottom line is that no matter how thin you slice it, no matter how trivial the contribution to a sound monetary policy, good advice to the Fed is extremely valuable. Monetary economics is quite important, too important to be left to amateurs. Unfortunately, some of our most important monetary policymakers have relatively little training in the field.

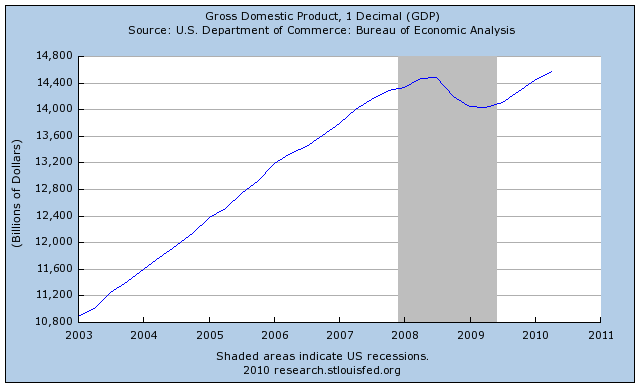

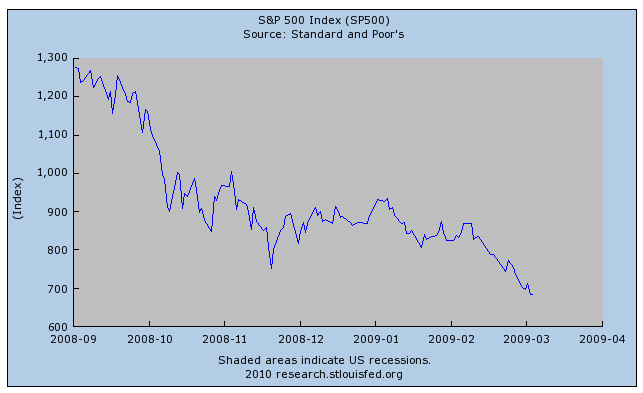

BTW, economists at the Fed must be high-fiving themselves after I allocated $4.5 trillion in wealth creation to their brilliant policy ideas. But before they get too excited, and start dreaming about where they’ll spend their money, I feel it necessary to point out that Fed officials still have some unpaid debts associated with an earlier policy boo boo:

Which proved very costly:

Tags: QE 2

15. October 2010 at 14:28

Scott. Oh! How I wish for a “meagre” half mil! But in my post this morning I was a bit frustrated with Bernanke´s talk. He didn´t even mention PLT/NGDPT as was done in the minutes. Stephanie Flanders had the “strongest” rhetoric, saying B had Declared war (not on China, but on deflation). And yesterday I put up a long post to help people “understand the terms of the debate” that´s coming up in the November meeting. For those that understand portuguese:http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2010/10/14/o-mercado-so-pensa-%e2%80%9cnaquilo%e2%80%9d/

From browsing the blogs, you get the feeling that many people don´t understand PLT/NGDPT and are “afraid”:http://blogs.ft.com/gavyndavies/2010/10/14/should-the-fed-adopt-a-price-level-target/

Others misunderstand it completely:http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2010/10/inflation-targeting-proposal-exercise.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+MishsGlobalEconomicTrendAnalysis+%28Mish%27s+Global+Economic+Trend+Analysis%29

15. October 2010 at 14:41

“Surely an extra $5 trillion in real wealth is something.”

This is the part I struggle with. There wasn’t more stuff after Bernanke’s speech today. There weren’t more goods or services available.

So how was there suddenly $5 trillion more of real wealth? That doesn’t make sense to me.

The link between the real and the nominal economy is still mysterious. I’m reading as much as I can on this topic (including here), but I’ve got to admit that Robert Higgs makes a lot more sense than Paul Krugman.

BTW, I can think of 5 ways to push string just off the top of my head.

15. October 2010 at 15:07

I somehow stumbled across your blog almost from your first post and feel you do deserve a lot of credit for helping to push monetary policy to the top of the agenda.

‘ Unless you want to be a complete ostrich, I don’t see how anyone could seriously deny that over the past 6 weeks the world equity markets have been repeatedly reacting to a long string of Fed statements and press releases. ‘

There are lots of ostriches around. I listened to a market economist earlier on Bloomberg arguing that the rise in equity markets this month has nothing to do with the prospect of QE2. Apparently it is all to do with earnings season just around the corner. The arguments against the Fed easing are getting more absurd by the day. ‘ It will be ineffective because it is pushing on an inflationary piece of string.’ One has to conclude that there are other agendas lurking beneath the surface. It simply offends some people that if the Fed do their job then Fed policy can be highly effective. Some folks do not like the thought that the price level can be anything that the Fed want it to be.

15. October 2010 at 15:44

Richard W,

I agree that the arguments are getting more and more ridiculous. I have heard, from people who I would classify as right-wing, arguments that are so drenched in late 1930s Keynesianism that Joan Robinson* would be shocked.

In the last two weeks, I have noticed a certain conflict in The Economist: on the one hand, some writers saying “there is nothing more that monetary policy can do now that interest rates are zero” and (only slightly worse) “QE might have little effect, because the banks are not lending much” (one might as well say that putting any amount of water in a sand-bucket will not make it soggy, because previous drops of water put on that sand have just dried up) contrasting with other writers talking about higher inflation targets and even price level targeting.

At least the monetary policy debate is back on the table, after all this fiscal nonsense about tax cuts, spending cuts and other more easily understood (and partisan-friendly) matters.

* Joan Robinson, of course, accidentally created the reductio ad absurdum argument of the equivocation of monetary economics and interest rates: money was not easy in Germany in the early 1920s, because nominal interest rates were not low!

15. October 2010 at 15:45

@Steve

It is true that Bernanke didnt dig a copper mine or start a business with his speech. However, what he did do (or rather what it now looks like he will do) is allow those types of things to occur in greater abundance. Because there is price stickiness, bouts of deflation or disinflation (caused by nominal demand shortfalls) lead to unused resources over a 1 or 3 year adjustment period, the converse holds too. Because Bernanke removed some uncertainty regarding future policy, the probability of reversal now appears higher, and thus the probability weights investors place on various future stock return paths shift in a positve direction, leading to higher real equity prices. The wealth is created because we just found out the adjustment period will be shorter. It is all about wage and price stickiness, without that the story doesn’t work.

It is like we were all subsistence farmers in a drought, and Bernanke had a monopoly on water. He essentially just told us that he will be most likely be supplying a bigger volume of water than what everyone believed 6 months ago. We need not wait for the rain now because Bernanke finally realized we were dying. Though the extra water is only helpful because we are in a drought (below potential RGDP and under disinflation)

15. October 2010 at 16:04

Scott wrote:

“I feel like a lazy bum. This morning Ben Bernanke created $250,000,000,000 in new wealth before I’d even finished breakfast.”

I never feel like a lazy bum. Two days a week I have to schlump out of bed at the crack of dawn to teach a class one hour away on Monetary Policy. The rest of the days I either tutor mathematics, statistics, physics or economics at UD at $14 or $22 an hour depending if it is individual or group or grade econ tests in Monetary Economics for an Associate Professor at UD at the $14 an hour rate. All told I’m working 70 hours a week. I’m dog tired.

Meanwhile I’m supposed to find time to do my original research in the area of the influence of tax structure on economic growth. Would someone please throw me a life-ring? (That is to say some kind of a real job actually supporting what I believe is research in something incredibly important?) Why is this, a subject which is so important, so hard to find support for?

15. October 2010 at 16:07

1. No wealth was created. Wealth is HARD ASSETS, the price you place on them is an illusion. What matters is who owns the hard assets.

2. Any effort of pundits is Marginal from a million other paths. If Obama had not been elected, and done a bunch of stimulus, freaked out local wealth and aided bankers… the Fed would be further along on QE…. Hell, if McCain won, we wouldn’t even have to cajole the Fed.

3. Suddenly Scott, you jump back to targeting 2% is OK (after just telling me it wasn’t). Eventually I’m gong to FORCE you to answer the point: When inflation is at 2%, and unemployment is at 8.5%+, NO MORE QE. In fact, when inflation 2.5% and unemployment is 8%, it is time to suck money out of the Economy. This is the policy…

I’d REALLY like to see more discussion of Cochrane’s approach because the way I read it… all the new money that flows into the system GOES DIRECTLY TO INVESTORS, is this correct?

Suddenly the Fed CPI Future’s market lets my grandmother bet on Deflation and if she is right… the printed dollars that bring the CPI price back up to level go to her.

And thus the side effect is that the Fed is no longer buying Treasuries? And since they aren’t buying Treasuries, demand for them goes down and the cost of Federal borrowing goes up?

Which forces Fiscal Sanity on us? is this your read of it?

15. October 2010 at 17:30

Wealth is not hard assets. Hard assets that sit idle create no wealth. Wealth is the value that hard assets can create, if they are put to work in a well-functioning economy. The Soviet union was never short of hard assets. It just wasn’t very good at creating value with them.

15. October 2010 at 17:40

Morgan,

I’ll make a bold prediction (something I very rarely do). Based on the current candidates, if the Republicans actually take control of the House and the Senate this fall you’ll see the biggest implosion of AD in a seculum. And what will follow will be the largest deficits as a percent of GDP since WW II. So much for fiscal sanity.

15. October 2010 at 17:52

Steve and Morgan,

It is extremely important we understand the effects of deflation on underutilization of resources. In normal times, with low inflation, an employee produces slightly more than what he or she is worth to the company and their customers. When deflation starts, wages are very hard to reduce and companies first reduce headcount at first to keep the company alive at least. All companies do this at once, creating an unemployment and high savings rate among those employed to slacken demand and further lead to more cuts.

This all leads to low returns on fixed costs. If you bought an equity offering from a company at the peak in early 2008, you would have received drastically negative returns. No matter how much companies reduced headcount, they could do little about fixed costs and profit suffered as a result.

The equity gains from QE announcements show that the markets expect companies to see higher utilization of fixed costs, resulting from lower unemployment and higher consumption due to QE. A plant sitting idle may as well not be there at all and inflation ensures that the plant actually makes stuff, increasing our real wealth S a result.

15. October 2010 at 17:57

Just want to note that I typed all that out on my iPhone and I apologize for the mistakes. I tried to fix them all, but it is hard to review your post on an iPhone.

15. October 2010 at 17:58

Marcus, I agree that it’s disappointing in a absolute sense, but relative to his earlier statements it’s quite a shift. He’s saying they need more stimulus and they will do more stimulus. He wasn’t saying that in August.

Steve, Wealth is the present value of future consumption. The expected level of future consumption just went up a bit.

Richard, Thanks for your support. Suppose an angel told the investment guy that the Fed would do more than expected on November 3rd. Would he be smart enough to load up on S&P 500 call options on the 2nd, or is he really the ostrich he claims to be?

W. Peden, Yes, I’ve used that Joan Robinson argument a few times myself. I’ve also noticed a few right wingers making a pushing on a string argument. Where did that come from, the one thing the right used to have going for it is that they never fell for the liquidity trap arguments. Now even that is gone?

JPIrving. that’s a good point.

Mark, That’s a good question. You had the bad luck to come on the market right after the Fed engineered a big drop in NGDP growth.

Morgan, I didn’t say it was OK, I said it was better than 1%, the current rate.

Nick, That’s right.

15. October 2010 at 18:06

Hi Scott, long time reader first time commenter.

Firstly congratulations on your wealth creation efforts! I hope you have spotted your easy money making opportunity: buy lots of stocks, then convince the fed to print more money.

I have a question about fed-speak which I hope is not too off topic. I have always wondered why they speak to the public in code, and never heard an explanation. Surely uncertainty about the fed’s future actions is bad for the fed? Wouldn’t it hamper their efforts to control inflation and output because it makes them less sure of how the market has interpreted their statements? [apart from info they can glean from asset prices] If future monetary policy is so important for current inflation / output then surely for the fed stating clearly the future path is important?

Thanks!

15. October 2010 at 18:12

Professional economists disagree with each other on these matters almost as much as amateurs. The primary difference is that professional economists make good arguments for bad ideas, while amateurs just make bad arguments regardless.

15. October 2010 at 18:13

@Nick Rowe,

In other words, wealth is energy in motion with lots of velocity, throughout entire systems.

@Mark A. Sadowski,

Index cards from volumes of notes! Even if you’re dog tired. That is, unless you do all your work by computer. One index card at a time got me back on track, trying to get ready to get the nerve to find a good publisher.

15. October 2010 at 18:16

JPIrving,

Thanks for the reply.

I understand (or at least think I understand) the long term impact of monetary policy. My questions are about the mechanisms by which monetary policy works its way through the real economy to create those effects. In the pathological cases of extreme inflation or deflation, those mechanisms are obvious, but how do the operate under normal circumstances? I think that is a more subtle problem than a lot of people assume.

Prof. Sumner may have had his tongue deeply in his cheek when he wrote that Bernanke created $250,000,000,000 of new, real wealth this morning, but pundits and policy-makers actually believe that is what happened. That’s a bad thing.

I disagree with your water analogy. Bernanke may be able to create money, but he can’t create wealth. He’s a Rain Maker promising to bring water or, a better analogy, he’s tricking us into making Stone Soup. If QE2 works, he gets credit for having created circumstances under which other people can create wealth.

But if Higgs and other are correct, the economy is jammed up by uncertainty that goes far beyond the money supply, QE2 will be worse than useless.

15. October 2010 at 18:28

Wealth cannot be printed. And wealth created by expectations, can ONLY BE BANKED, by the guy who SELLS at the peak… trust me here, I witnessed it personally with Mark Cuban. EVERYONE else finds out the wealth wasn’t real.

Wealth’s only legitimate creation comes from capital formation (savings). Productivity gains are the only true from of growth. And Productivity Gains can ONLY be positively financed by honest capital formation.

When Scott says “who cares” how much inflation there is as long as we get 5% NGDP, its time to head for the commodities markets (hard assets).

Like so many layers of an onion… getting down to it is very hard here.

2% level targeting makes the market very happy. You’ll get the CNBC Tea Party crowd and keep them. At 2%, you have MF’s full support.

But what if unemployment is 8.5% then? Now you are just plain old Krugman, seeking to steal from the savers – so the Feds don’t have to cut Public Employee salaries.

That’s the question… when the Fed is now on target, what’s your argument going to be?

15. October 2010 at 18:36

Prof. Sumner,

You replied to me while I was proof-reading my reply to JPIrving, so I may have put words into your mouth. Apologies if I did.

You said, “Wealth is the present value of future consumption. The expected level of future consumption just went up a bit.” So Bernanke literally created $250,000,000,000 of new wealth just by giving a speech?

Is that definition of wealth widely accepted? In most of the reading I’ve done, wealth is sum of the goods and services available in the economy. It’s aggregate supply and the goal of monetary policy is to support an environment which helps AS grow.

What do you think of that view?

I see you’ve done a couple of hours on these issues with Russ Roberts. I’m new here, so let me listen to those before I dig this hole any deeper.

Steve

15. October 2010 at 18:46

Rebecca Burlinggame,

You wrote:

“@Mark A. Sadowski,

Index cards from volumes of notes! Even if you’re dog tired. That is, unless you do all your work by computer. One index card at a time got me back on track, trying to get ready to get the nerve to find a good publisher.”

It’s not for me of course. People who know me already joke about my lack of any personal ambition. I’m concerned purely for my research. I’m convinced that I’m on to something that has important public policy implications. I just wish I could get more financial support to help me to support my claims.

My own department has (for some unknown reason) completely abandoned me. I still believe in my research (as does my advisor, James Butkiewicz).

15. October 2010 at 18:47

Bernanke and co. can create wealth, in a sense. They can create a means by which the plans of savers and investors can be coordinated. Of course, they can also create discoordination by sneezing at the wrong moment and spooking the market.

I don’t like the Fed and would prefer to have it abolished. I believe a free market in money and banking would provide for our monetary needs much better. By that standard, I consider the Fed to be a destroyer of wealth. But relative to the speech that Bernanke could have given, which it seems is the benchmark that Scott is working from, Bernanke probably did “create” wealth.

15. October 2010 at 18:53

God what I’d give to have you actually ANSWER Mish… cal him out, debate him:

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2010/10/inflation-targeting-proposal-exercise.html

15. October 2010 at 19:01

Mark A. Sadowski I will take that bet.

The loser must wear a tshirt saying, “I was wrong on the internet” for a full day when you go to grad school (preferably when the person is TAing a class) and post a full mea culpa on this blog.

Any details of the bet you wish to work out so we can finalize it?

15. October 2010 at 19:13

[…] acordo com Scott Sumner (aqui), eu “teria direito” a aproximadamente U$ 1 Bilhão!!!: In other words, we at […]

15. October 2010 at 19:14

Doc Merlin,

Agreed.

But we must work out the terms in full. I believe that the issue is the degree to which the markets are surprised (which may the devil in the details).

15. October 2010 at 19:17

Anyway, Scott, I predict oil, iron, copper, silver and gold will keep rising now. Also wheat, corn and rice will keep rising in price. Electronic goods will roughly stay level in price or edge downward some.

15. October 2010 at 19:22

@ Matt:

Excessive monetary inflation (I mean excess money printing not necessairly) excess CPI inflation also causes underutlization because of the flight to commodities.

15. October 2010 at 19:26

bah that close parenthesis should be after “CPI inflation”.

15. October 2010 at 19:28

I predict that the most important indicator of AD, which is the TIPS market, will suddenly shift south after the Rebubs unpredictably take control of the entire Congress. Any takers?

15. October 2010 at 19:30

A “fellow libertarian” has strong doubts. At the very end he shows “ignorance”!

http://jeffreymiron.com/2010/10/bernankes-speech-and-quantitative-easing/

15. October 2010 at 19:46

Oh, by the way, the yield on the 5 year TIPS reached -0.49% yesterday. Any comments? Or we just going to ignore it and go harumph, harumph!

Just a bunch of staltwart idiots, eh?

15. October 2010 at 19:47

A “New Monetarist” Nihilist:

http://newmonetarism.blogspot.com/2010/10/inflation-and-monetary-policy.html

15. October 2010 at 19:56

Modeled Behavior has very nice things to say:

http://modeledbehavior.com/2010/10/15/scott-sumner-takes-a-well-deserved-bow/

15. October 2010 at 21:01

Congratulations to Scott Sumner and for his discovery that QE boosts asset prices. Many of us predicted this blindingly obvious outcome when QE first started two years ago. So I bought some stock then and have done very nicely. Thank you Fed and Bank of England.

The problem with this method of boosting AD is that it only works via those who are asset rich. Meanwhile the unemployed underwater folk of Main Street are hung out to dry (apart from the ones who can find work building mansions and yachts). There is no conceivable logic, when boosting AD, to do it only via a small section of the population. How about boosting AD only via households and firms whose names begin with the letters A-G?

15. October 2010 at 21:36

Morgan,

I’m a big proponent of the view, that in the end, productivity is everything. Krugman predicted the Asian financial crisis by pointing out that productivity gains did not give the real returns necessary to justify the inflow of capital. It’s incredible that he then became the #1 bankrupt-the-government-and-crowd-out-all-financing-available-type fiscal stimulus advocates. Past a few select things, law enforcement, infrastructure, etc., government spending simply does not improve a nation’s productivity. Meanwhile, private financing in a market economy goes towards things which will increase our real wealth per capita, otherwise they won’t make money and won’t get investors.

Well, I should amend the last paragraph to say productivity growth is almost everything. In a deflationary environment, where cash can sit idle and not lose value and where AD has slackened considerably, capital will not flow. Every kind of worthwhile productivity improvement needs capital first. Some productivity improvements don’t require upfront investment, but those are typically hard to find since most of them have been done by companies already. Productivity improvements such as implementation of new IT systems, new machines, more fuel-efficient vehicles, etc. all require either cash upfront or financing.

It’s a very tough bridge to cross for libertarians, including myself when I was a very die-hard libertarian. The fact that a capricious government action, how much paper they print, has real effects on the free market is indeed very unsettling. But in the real world, people hold to the money illusion. Managers should, economically speaking, reduce wages rather than laying off but they don’t. Banks should lend out money at even low returns instead holding cash or cash equivalents, but they don’t for fear of a bank run or another market collapse. That whole Animal Spirits deal has some very real and very obvious effects on the real economy.

Doc,

You could say that every real good is a “commodity” and all commodities track the growth of the money supply. In this sense, commodity inflation is like high inflation for finished goods. High inflation has its own costs as inflation makes the monetary environment much more volatile.

I know you’re talking more about investments being diverted to commodities due to high inflation. Well, there are two ways to invest in commodities, ETF’s and actually holding onto the damn things. ETF’s are a zero-sum game which is all on paper relative to real commodities. When an ETF is bought, 100% of the cash is spent in some way by the seller.

So commodities crowd out real investment through investors who actually have wheat silos, gold vaults, oil tanks, etc. For them, most of their money goes to the costs of recovering the commodity, not to be for other purposes in the general economy. That small segment of investors do take away from financing for the real economy, but they’re certainly do not outweigh the gains when you go from 0% inflation to 2% inflation.

15. October 2010 at 21:37

Ugh, that should be “they certainly” in the last sentence, and probably some other typos. I wish they had an edit button.

15. October 2010 at 22:00

@Matt

“So commodities crowd out real investment through investors who actually have wheat silos, gold vaults, oil tanks, etc.”

I couldn’t agree more.

“That small segment of investors do take away from financing for the real economy, but they’re certainly do not outweigh the gains when you go from 0% inflation to 2% inflation.”

This I don’t agree with, because commodity price movements are far far more severe than CPI. The first ~5 months of the recession for example we had about 50% non-annualized inflation (so the annualized rate was over 100%) in raw materials. This looks like a /massive/ supply shock to the real side of the economy, even if it is barely reflected in CPI data.

15. October 2010 at 22:12

Scott, perhaps you should see if you could find a student to collect the times of every “Fed speak” (Official Fed statements or Bernanke, any of the Fed chairs, or other people markets follow for indication about Fed policy) about economic situation, mark them as positive neutral or negative – and then check what the market reaction was.

If you could figure out a way to measure whether the “Fed speak” was more positive than market expectations without looking at the stock market data, you could do a really nice piece of research work on Fed’s ability to move markets on pure statements alone. 🙂

15. October 2010 at 22:22

@Mikko

What does it mean to be “positive” or negative. In the stock market increased nominal prices aren’t necessarily positive.

For example:

If the USD goes up relative to other currencies and commodities and the stock market also goes up, thats positive.

If the USD drops relative to other currencies and commodities, and the stock market goes up , it is indeterminate based on the magnitude of each.

15. October 2010 at 23:21

Doc,

That’s a pretty convenient timeline. It’s like saying in the couple of years before recessions, stock prices will always go up astronomically and then use stock data from 98 and 99 to justify this argument.

Just because commodities are “real” does not mean they don’t experience bubbles. Oil in 2008 had all the properties of a bubble. End buyers thought they were lucky to get oil at 120 and hold months worth of inventory, because soon it would be at 200. The oil had to go somewhere and inventories were massive. Bubbles get popped though and when oil started to go down, people drew from inventories instead of buying on the market and the price dropped like a rock.

In that specific case, where people panic about either the availability of oil or, with the case of gold today, the future value of the dollar, commodity prices do skyrocket. However, commodities do eventually settle around the rate of inflation, plus or minus the real supply and demand issues.

Today, gold’s price likely exceeds any sensible real value. Basically, a bunch of Ron Paul supporters have been willing to spend a lot of money to hold something real and pay a vault to store their gold and earn zero interest. As this illusion ends and they find gold can in fact drop in price rather dramatically, gold will drop like a rock as well when all the Ron Paul guys sell and only jewelry companies and industry buy.

Now, I actually do think commodity prices over the long term should be considered by the Fed in making monetary policy. Through the 2000’s, 3rd world markets did two things. They boomed and they soaked up a lot of the world’s extra dollars. Those dollars were spent first on food or energy and then second on finished goods. “Core CPI” is meant to take away the volatility of commodities, but instead the core CPI was significantly below the true CPI throughout the 00’s, rendering the volatility argument useless. Core CPI underestimated inflation and the Fed should have considered the true CPI and raised rates more than they did.

However, the long-term appreciation in commodities in the 00’s was still due to general inflation plus a real supply or demand factor. Inflation does not automatically translate to a huge run-up in commodity prices once the bubbles pop. It certainly didn’t in 90’s with 2-3% inflation and consistently low commodity prices in just about every category.

15. October 2010 at 23:48

Why is monetary value of any financial instrument wealth?

Value of stock markets only measures what part of global economy owners of common stock in existing companies can claim (as opposed to workers, corporate bond holders, preferred share owners, government, non-traded companies, future companies etc.). This isn’t that much different from bond markets.

How do we know how much of these changes are due to increased total growth, and how much due to particular sector’s increased claim?

Example 1. If company has $10bln worth of assets and $8bln in debt, value of its shares will be $2bln. 1% increase in assets’ worth to $10.1bln increases share values by 5% to $2.1bln – rather drastically exaggerating the effect.

Example 2. Let’s say this debt is all due in 5 years at fixed nominal value. Increasing inflation expectation from 1% to 2% reduces real value of this debt by 5% to about ~$7.6bln real. Now that shareholders will own 24% not 20% of company in 2015, value of shares immediately increase by 20% to $2.4bln in spite of no change in real value of assets.

I’m not claiming changes in share prices and changes in global wealth are unrelated, but your claims seem rather exaggerated.

16. October 2010 at 00:07

Marcus Nunes,

I notice that stephen Williamson is getting all worried about M1. However, as has been repeated a lot on here by now, an increase in narrow money doesn’t mean that the money supply as a whole is increasing, anymore than putting on fat necessarily means putting on weight. As for M2, which is somewhat broader (though still not as good as M3) I wouldn’t say there is that much of an upward trend-

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/current/

– since M2 is still on an annual growth path of 3%.

Anyway, I would say that the money supply statistic to look at is M3-

http://www.shadowstats.com/alternate_data/money-supply-charts

– which is still in negative territory, albeit not as bad as earlier during the year. M2 growth is still, as that graph shows, in anemic territory. I don’t think that there is any money supply evidence for significant inflation next year yet and there will not be until there is a sustained growth in M3.

As I’ve said before, the similarities between the US monetary dialectic now and in the 1930s (and the dialectic in Japan in the 1990s) is so uncanny that it is chilling: people are worried about inflation even as they are mired in deflation. It is like worrying about having too much blood when you’re bleeding to death.

16. October 2010 at 02:54

Steve,

How can buying bonds immediately affect anything? Sure the money gets out in a few months or a year, but how can it affect asset prices right away? I am a recovering Austrian so I’ll try and tell you the story that persuaded me.

A natural experiment: Industrial production, the DOW, the CPI 1930 to 1939. After the April ’33 devaluation deflation stops the DOW *immediately* soars in real terms until 1937. Real industrial production takes off too, and this is all while FDR is busy trying to destroy the country, Hitler is stealing land in Europe and uncertainty is super high.

Why this behavior? I’m still learning the New Kenyesian model, but the basic idea is that inflation today is proportional to the discounted future path of *expected* “output gaps” or marginal cost for the whole economy. This forward looking behavior means that we don’t need to wait for banks to lend the newly printed money, agents in the economy reckon they will gradually lend it, and will bid up assets TODAY with their own idle money. As long as Bernanke can affect market expectations of the future path of marginal cost, he can affect relatively short run real behavior.

This result was found through a painful process of modeling behavior from micro level agents, up to the “New Keynesian Phillips Curve”. I don’t really buy this derivation so much, what convinces me is that one can model inflation reasonably well using only previous inflation data, and a simple model for future marginal cost. If you are up for it, you might type “New Keynesian Phillips Curve” into google and read for a bit.

What is really comes down to is greedy businessmen and traders. They adjust their behavior to get rich from the future implications of the FEDs decisions. If you were the only one that understood MV~PY (eventually), you could borrow money and make trades before monetary policy affected prices, you would become rich within a year. This is really hard though because thousands of smart and greedy people do this everyday.

We will find out if Higgs is right. That’s what I love about economics, the market is the final arbiter.

16. October 2010 at 03:18

Scott, you will hate this: http://www.bos.frb.org/RevisitingMP/papers/Reifschneider.pdf

16. October 2010 at 04:32

Mark Sadowski: From what you’ve written I gather you’re an econ grad student trying to write your thesis. I’ve been there.

One thing I realized very early in my graduate studies was that the daily professional activities of senior grad students and assistant professors were pretty much the same: Teaching and research. But the assistant professors get paid a lot more. So the object for a grad student should not be to do good research, it should be to get the degree and a decent job, and then do good research, when you’re actually getting paid to do so.

There have been a few people who did something really important with their thesis, like Paul Samuelson and Frank Knight, but they’re pretty few and far between. By the end of your third year of grad school you undoubtedly knew a lot more economics than when you started, and you should expect that you’ll learn even more as time goes on. But that also implies that your ability to do good research will also improve over time. So don’t make the mistake of trying to make your thesis the best work you’ll ever do. Just get something done, get paid, and keep moving.

16. October 2010 at 05:46

Matt,

“Some productivity improvements don’t require upfront investment, but those are typically hard to find since most of them have been done by companies already. Productivity improvements such as implementation of new IT systems, new machines, more fuel-efficient vehicles, etc. all require either cash upfront or financing.”

Matt, lack of the ability to get credit, capital, etc. is a POSITIVE trait because it forces liquidation, and some guys playing are left without chairs, and must start over finding a new place to make improvements.

GOOG, APPL, AMZN show clearly the GIANT TECH BOOM going on – it’s actually kind of freaking everyone out. No one can find anyone to hire, programmers are commanding massive salary increases.

And this leads to another mistake you are making – in this “deflationary” environment MONEY IS DESPERATE – forced to take out-sized risks trying to find returns, I hear it from everyone, no one says “I’m choosing to let my money sit, since we have deflation…” they say, “I can’t find anything Green and Growing!”

And when that’s the complaint – it’s because there isn’t enough destruction being allowed.

I’ve been spending some time reading over JOLTS data and I wonder why that side of things hasn’t lead to actual economic policy…

When turnover is up towards 6M job separations a month, thats when we see positive gains (more than 6M) – but down at 4M a month – add jobs looks harder.

The point being – we need to see and will see another 10-20% of the real economy move to the Internet… we need to be far more willing to TOPPLE shit like GM and TBTF banks – we need to set tax policy to encourage the new companies to kill the old companies.

16. October 2010 at 05:52

Sumner wrote:Sure the disappointing consumer data depressed prices a few hours later, but they remain 1/2% above the level they would have been without that easing..

I just don’t think that is a defensible statement. If I was an investor who bought into ‘String Push Theory’ I would be tempted to take profits after the mini-rally.

In AZ home prices doubled from 2002 to 2006 and have since returned to 2002 prices. I don’t think you can say that AZ home prices would be half what they were in 2002 without the run up before hand.

This is not say that I don’t believe Fed statements effect stock prices. But placing causation for specific movements seems like a bit of mugs game, fraught with the same cognitive biases of believing you can beat the market.

Doc Merlin- I don’t quite understand your model for this regarding commodity movements and where it differs from Sumner’s specifically.

16. October 2010 at 08:24

A Fine (US) Whine by Krugman

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/16/a-fine-european-whine/

Just substitute ‘US’ for ‘European’ and ‘China’ for ‘US’ and you have all of Krugman’s posts and articles about China.

Why, oh why can’t we have a better press corps?

16. October 2010 at 10:54

TravisA,

It’s interesting that Krugman talks about “tight monetary policies” here in Europe. I can only guess what he means (for all I know, he has confused monetary policy and fiscal policy) but it’s more than a little odd. For instance, UK CPI growth is about 3% right now, compared with 1% CPI in the US.

16. October 2010 at 11:04

)GT

“Doc Merlin- I don’t quite understand your model for this regarding commodity movements and where it differs from Sumner’s specifically”

Ah, I am arguing that stock price increases don’t necessarily provide a good signal, if they are accompanied by upward commodity price movements and downward movements in USDX. All it shows is that the market expects future monetary increases, not that the market sees it as a good thing.

16. October 2010 at 11:37

@ W. Peden

In fairness to Paul Krugman he was referring to the ECB and not the BoE. The BoE will probably conduct more QE over the next six months. My guesstimate would put the chances as 70/30. There is really only one hawk on the MPC.

16. October 2010 at 12:32

Did you happen to see John Taylor and Alan Blinder on NewsHour Friday? Taylor is still a QE2 skeptic and argues the Fed is creating too much uncertainty. Blinder argues the Fed should pay negative interest rates on excess reserves.

16. October 2010 at 15:44

Jeff,

That makes a lot of sense.

But I think I am forced by financial circumstances to delay my dissertation defense until the spring. After the defense the job search is sort of like jumping out of a plane without a parachute and hoping for the best.

Wish me luck.

17. October 2010 at 05:39

Brit, Alas, I underestimated my own influence.

You raise a good question about speaking in code. My hunch is that the Fed doesn’t know exactly what it wants to do, as there are divisions withing the Fed. In addition, they worry about a loss of credibility if they failed to hit their targets. By speaking in code, they don’t get blamed if things don’t turn out the way they expected, or hoped.

But I agree about transparency. I think policy would work better with an explicit nominal target, level targeting.

Lee Kelly, Good point.

Steve Fritzinger, I disagree, I think they can create wealth by making the price system work better (through stable NGDP growth.)

You asked:

“Is that definition of wealth widely accepted? In most of the reading I’ve done, wealth is sum of the goods and services available in the economy. It’s aggregate supply and the goal of monetary policy is to support an environment which helps AS grow.”

You are confusing wealth (present value of all future consumption) with income, current production.

Morgan, See answer above to Steve.

Lee Kelly, Yes, in practice the Fed often destroys wealth, so consider the speech and indication that the Fed plans to destroy $250 billion less wealth than before.

Doc Merlin, Are you smarter than the markets?

Marcus, Yes, I saw that. I like Miron’s views on drug legalization much better.

And thanks for all the links. I’m having trouble keeping up right now. And I need to do another essay for The Economist.

Ralph, If the Fed would do enough QE to boost NGDP growth up to closer to full employment, then most of the gains would go to workers.

Don’t forget that it is also true that stock prices fell much more sharply in 2007-09 (as compared to wages) during the period of tight money. So it’s not surprising they also respond much more on the upside. Even today asset prices have fallen much more sharply than wages since 2007.

Mikko, The easiest way would simply be to look at Fed’s target rate announcements that occur precisely at 2:15, compare actual to predicted in the fed funds futures markets, and check stock market responses over the next 10 minutes. I already know what the result would be.

Tomasz, You said;

“Why is monetary value of any financial instrument wealth?

Value of stock markets only measures what part of global economy owners of common stock in existing companies can claim (as opposed to workers, corporate bond holders, preferred share owners, government, non-traded companies, future companies etc.). This isn’t that much different from bond markets.”

Technically you are right, but there is a strong presumption that I am right. Most economists think stimulus also helps workers, not just capitalists. Indeed there is now stronger support for QE on the left than the right. I don’t think economists like Krugman would support QE if they thought it was merely taking money from workers and giving it to companies.

Also, historically speaking a strong monetary stimulus does tend to lower unemployment. We aren’t there yet, as monetary policy needs to be more stimulative.

Arash, Yes, He misses the point on Japan.

OGT, You said;

“I just don’t think that is a defensible statement. If I was an investor who bought into ‘String Push Theory’ I would be tempted to take profits after the mini-rally.”

Sorry, but this statement is simply indefensible. EVEN ECONOMISTS WHO DON’T ACCEPT THE EMH, DO ACCEPT THAT STOCK PRICES ARE ROUGHLY A RANDOM WALK IN THE SHORT RUN. That part of the EMH is completely uncontroversial. Otherwise every time there was a bump up due to transitory factors, arbitrageurs could make easy money by selling the indices short.

If you don’t think the Fed has been affecting the market recently, then all I can say is that you haven’t been paying attention to the market. The correlation is as clear as anything you are ever likely to see. If there is a strong market reaction right after 2:15 November 3rd, will you also discount the significance of that?

Travis, A That makes at least three of us who noticed the same thing. (Blogger Bob Murphy.) Some posts virtually write themselves.

He’s says China’s actions hurt us, because there is nothing the Fed can do to offset the effect, but our dollar depreciation doesn’t hurt Europe, because they can simply use monetary policy to offset the effects. That’s got double standard written all over it.

JTapp, No, but I knew that Blinder supports negative rates on reserves.

17. October 2010 at 06:41

Richard W,

Probably, but he should have said the ECB rather than “the Europeans”. The British are Europeans as well, even if they are loathed to admit it.

In fact, I would argue that the BoE has been one of the best central banks in the world since late 2008. They understood the essence of the crisis very quickly, got inflation back up to 3% by 2010 and they are poised to do more if there is a slowdown in the British economic recovery.

I agree that QE is likely. I think, if we see two (or even one) quarter of significantly slowing UK growth, there will be substantially more QE. Another measure, if there is a sustained downturn, would be to release a bit of pressure on the banks’ reserve requirement programme.

At any rate, I think the MPC and the Treasury understand the task ahead of them: cut spending, keep interest rates low and be ready to unleash monetary stimulus in the event of a slow-down.

17. October 2010 at 10:22

I think the stock markets are up in the US at least partly because quarterly earnings are surprising to the upside, profitable corporations have announced stock buyback programs, and other data are showing that the double dip scare over the summer was at least premature. Talk of Fed easing is part of the mix, to be sure, but not the only piece. I think there is, at best, confusion among market participants as to whether quantitative easing combined with interest on reserves has any measurable effect on economic growth.

I detect a form of market worship going on here, this assumption that the market is always right and that its movements can be reliably attributed to particular news items.

17. October 2010 at 11:55

@ W Peden

I would push it more to early 2009 rather than late 2008.

I think what the problem is the Fed out of all the main central banks are the least independent. That is not a good situation for the most important central bank in the world. Monetary policy in the US has been horribly politicised. How can it be good monetary policy when the Fed have to consider what politicians in Congress will think of the policy, rather than conduct policy based on its own merits? Market participants should not have to consider whether a change in Congress will impact monetary policy as that does not suggest the central bank was very independent in the first place.

As you know the BoE nowadays are just left to follow what they consider the appropriate policy. Sometimes they will screw up and other times they will do the right thing. Apart from a tiny minority of politicians on the right there is just nothing to compare with the hysteria about monetary policy all too prevalent in the contemporary US.

Although the governor will write to the chancellor requesting authority for more QE, it is really a rubber stamping exercise as the Treasury indemnify the Bank balance sheet against any capital losses. The idea that the chancellor would refuse a request from the governor when the MPC thought the policy appropriate would be unthinkable. The least democratic is best in my opinion when it comes to monetary policy.

17. October 2010 at 19:20

“Doc Merlin, Are you smarter than the markets?”

I never said I was smarter than the markets. I am saying that you cannot read marked rallies as anything more than adjusting the proper prices of things. Unless you have a market specifically tailored for predictions, trying to read too much into a market rally or decline is fraught with danger of cognitive biases.

I am saying that market reactions are hard to read you can’t say that every nominal stock market rally is good. If you want to extract information from price changes in markets, you have to have markets either tailored specifically for it, or have very good models for how the relative prices work.

18. October 2010 at 07:04

Of course, if there’s some hidden flaw in your reasoning, and you are leading the Fed down the primrose path to some enormous economic disaster, we’ll know whom to blame, and how much to charge you (in particular) in damages. (For egging you on I might have to accept 1/1000th of the blame that fell upon you. I would have to declare personal bankruptcy!)

18. October 2010 at 18:10

Doug, No I think the market is often wrong (i.e. 1987), it’s just that I see it as being less wrong than other pundits. I see strong evidence that the Fed is affecting the markets. There have been a number of very strong moves right after Fed announcements. Obviously the specific numbers in this post may be wrong, but I’m confident about orders of magnitude. I’ve seen a trillion dollars gained and lost with 10 minutes of a 2:15 announcement. Look at the daily chart when that happens–it is striking. There is no way it can repeatedly happen out of coincidence.

Doc Merlin, If you are not claiming you are smarter than the market, then I don’t follow your argument. As that seemed to be the clear implication.

Philo, If so, torture and death would be too good for me. I could never repay the damage I’d have caused.

11. November 2010 at 14:45

[…] and I don’t realistically think I can have more than a tiny impact on the zeitgeist, but (as I argued earlier) even a tiny impact is important when the stakes are […]

10. May 2011 at 08:38

[…] 6.QE2ãŒç™ºè¡¨ã•ã‚Œã‚‹ã‚„ã€æ ªä¾¡ã¯å€¤ä¸ŠãŒã‚Šã‚’示ã—ã€TIPSスプレッドã¯æ‹¡å¤§ï¼ˆâ‰’期待インフレ率上昇)を見ã›ãŸãŒã€ã“れら2ã¤ã®ç¾è±¡ã¯ã€Œæµå‹•æ€§ã®ç½ ã€ãƒ¢ãƒ‡ãƒ«ãŒäºˆæ¸¬ã™ã‚‹ã¨ã“ã‚ã¨ã¯æ£å対ã®ç¾è±¡ã§ã‚る。ã©ã†ã‚„らマーケットã¯ã€Œæµå‹•æ€§ã®ç½ ã€ã¨ã„ã†ã‚¢ã‚¤ãƒ‡ã‚¢ã‚’ãã‚Œã»ã©è²·ã£ã¦ã¯ã„ãªã„よã†ã§ã‚る。ãã—ã¦ã“ã®äº‹å®Ÿã ã‘ã«ã‚ˆã£ã¦é‡‘èžæ”¿ç–ã¯ãã®æœ‰åŠ¹æ€§ã‚’ä¿ã¤ã“ã¨ã«ãªã‚‹ã€‚ã¤ã¾ã‚Šã€ãƒžãƒ¼ã‚±ãƒƒãƒˆãŒã€Œæµå‹•æ€§ã®ç½ ã€ã®å˜åœ¨ã‚’ä¿¡ã˜ã¦ã„ãªã„ã¨ã™ã‚Œã°ã€ãã‚Œã ã‘ã§çµŒæ¸ˆãŒã€Œæµå‹•æ€§ã®ç½ ã€ã«åµŒã‚‰ãªã„ã§æ¸ˆã‚€ã«å分ãªã®ã§ã‚る。 […]