What drives the unemployment rate?

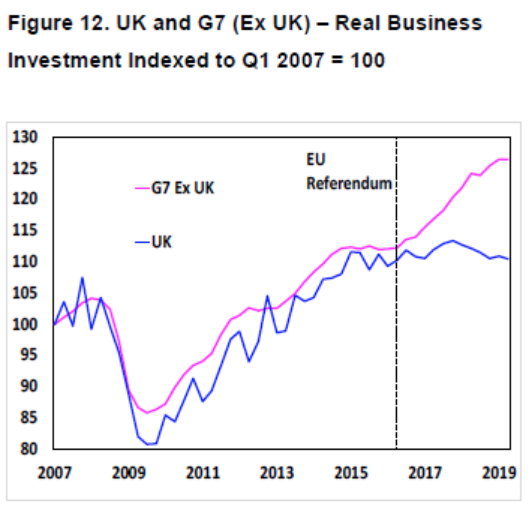

I was recently directed to an interesting Jason Douglas tweet showing a slowdown in UK investment—perhaps due to Brexit uncertainty:

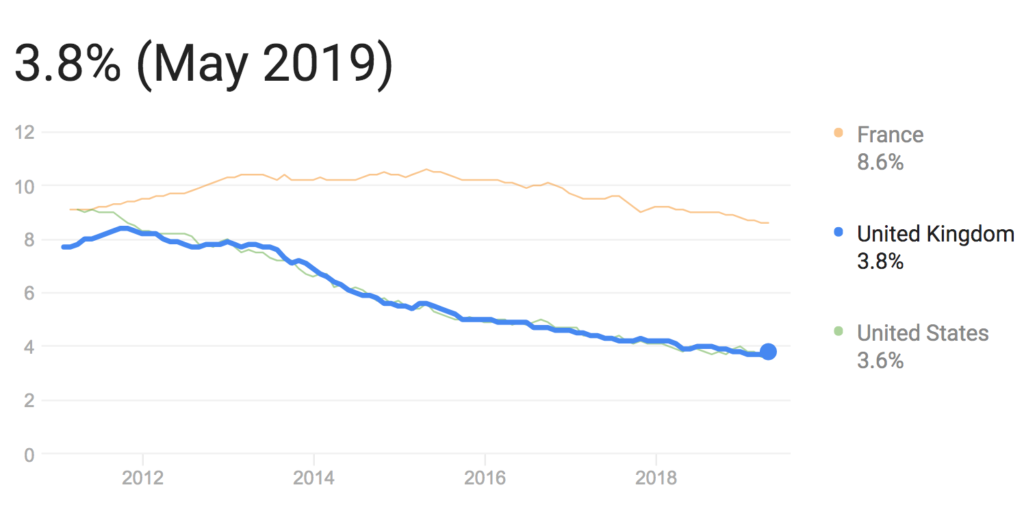

I was curious as to how this impacted Britain’s unemployment rate:

Wait; shouldn’t there be three lines? Look again, the US and UK have almost identical unemployment rates, at least since 2012.

In my view, investment shocks don’t have much impact on the unemployment rate. That’s why the recent slowdown in US investment (perhaps associated with the China trade war) has not impacted the unemployment rate in the US.

In the Keynesian model, investment is quite similar to fiscal policy. Either expansionary fiscal policy or positive “animal spirits” among investors will lead to faster growth and higher employment. But does the data support that?

In 2014, the Japanese sales tax increase did sharply slow GDP growth for a quarter, but the labor market was almost entirely unaffected. The unemployment rate kept declining at the same rate, despite Keynesian scare stories about “recession”. (In contrast, Japanese unemployment rose sharply when NGDP fell in 2008-09.)

The case of the US austerity of 2013 was even worse for the Keynesians. Both the labor market and GDP did well, despite the budget deficit falling from $1050 billion in calendar 2012 to $550 billion in calendar 2013.

The Brexit shock probably slowed UK investment, and may have slightly slowed RGDP growth. But the labor market reflects monetary policy, and as long as policy keeps NGDP growth at a decent rate, the impact of these shocks on unemployment is negligible.

Of course that’s a big if. The Fed should cut rates by at least 25 basis points at its next meeting, to assure an adequate level of NGDP growth in 2020. Better yet would be 50 basis points, as they are still falling short of their 2% inflation target. The BOJ and ECB need far more expansionary monetary policies. I’d recommend they shift to level targeting and buy whatever it takes to hit the target.

PS. This doesn’t mean a slowdown in investment is not “bad”—it is. It’s just that the problem it creates is not unemployment; rather it’s slower growth in living standards.

HT: Mike Bird

Tags:

30. September 2019 at 12:08

Good post.

On the PS, your argument is basically that weaker investment growth will eventually have an impact on the growth of real GDP per capita. If it is not evident in unemployment, then it would show up in real wages or investment income.

At least for real wages, there was an initial negative impact on real UK wages after Brexit so that real wage growth was around 0% in 2017, but it has since accelerated back up to around a 2% pace in 2019.

30. September 2019 at 12:23

Investment in productive capital is what produces economic growth and rising wages. What America has been investing in is rising asset prices – thank you very much. What China has been investing in is productive capital. I’m not complaining about trade, I’m just pointing out the obvious. I’d also point out that this is an odd time to engage in a trade war with China, as China, with a populace with expectations of higher standards of living, is rapidly increasing consumption (and decreasing the savings rate). Economists are no different from real people: obsessed about the future but focused on the past.

30. September 2019 at 12:51

Very good post. How did we ever decide to define recessions the way we do? The old joke “a recession is when the guy down the street loses his job, a depression is when you lose your job” seems closer to the mark.

Given how fluidly people move in and out of the labor market nowadays (even in the 25-54 group), even the unemployment rate can seriously mislead us about the labor market, as we’ve seen over the past few years.

Better to look at total employment IMO. A sustained period (six months?) of lower employment would be a better measure of a recession IMO.

30. September 2019 at 13:21

Brian, You said:

“A sustained period (six months?) of lower employment would be a better measure of a recession IMO.”

I agree.

30. September 2019 at 14:47

Hi Scott,

Unrelated question, but a while back you mentioned you could imagine a system where reserves make up only 0.00001% of NGDP (it would still provide a nominal anchor).

Lets assume reserves were that small, 0.00001% in reserves AND we were in a cashless economy. Can you imagine the bank system functioning with such small amount of reserves/MB? Could it ever be exactly 0.0% at a moment in time, as long as it came along with the Fed’s promise that it will create reserves if a bank demands it?

Just trying to work through some extremes in my head…possible have the monetary base at exactly 0 for a short time as long its also promised that, when needed, the Fed will increase MB to what is needed to keep NGDP on path?

Also looking to see why reserves have become less important, and cash more important in regards to the monetary base in recent decades…

Thanks!

30. September 2019 at 16:19

Scott Sumner advocates lower interest ratees, trailing in the wake of Don Trump.

But what about quantitative easing presently?

The European Central Bank has gone back to QE, and the Federal Reserve has just tried out about $100 billion of QE in its repo program. Chair Powell indicated the Federal Reserve will no longer shrink its balance sheet and in fact the balanced sheet is again growing.

Others are calling for some sort of fiscal-monetary coordination, which sounds a lot like helicopter drops, which sounds a lot like Modern Monetary Theory.

Well, if the Fed does go to QE we will in effect have fiscal-monetary coordination or helicopter drops. Or we can pretend that the Fed plans to shrink its balance sheet at sometime in the future, but I think that option is now off the table permanently.

30. September 2019 at 18:09

PS–

In theory, higher wages would attract more people into the labor force, increasing the labor participation rate, but perhaps not affecting the measured unemployment rate much.

Also, you might well get a backward-bending labor supply curve with higher wages. If employees are paid enough, perhaps some spouses would drop out of the labor force to raise kids.

30. September 2019 at 18:54

Jim, if those promises were really certain, say eg as call options (on a credit line or so), wouldn’t they trade as reserves?

George Selgin writes that in a free banking system (almost) all reserves are precautioniary reserves. The Scottish banks mainly only need reserves for settlements between them, the general public by and large didn’t hold gold. Precautionary in the sense that payment flows are reasonably modelled by random walks with mean close to zero but non-zero variance, so the reserves mainly served as a precaution against being caught out by random fluctuations.

Eg the Scottish free banking system operated with about 2% reserves. And that was in an era without a lot of modern inventions that make settlements more efficient. Both technological and organisational.

Those 2% reserves where 2% outstanding deposits and notes, not of GDP. But it gives you an idea.

You could imagine a gold standard system where the banks are temporarily without any reserves. As long as they have enough capital, they could always try to rely on buying gold in the open market when demanded.

For fed reserves that’s slightly different, but as you suggest, if the fed had a credible promise to sell reserves on demand, that might work.

(The simplest such promises would peg the value of reserves (eg the value of the dollar) against the asset they promised to buy. Eg like a gold standard. If you think that would just be a system with non-zero reserves in disguise, imagine instead that the fed promises to keep gdp on target, but also to be eg treasuries at a price that’s at least half a high as the average they paid over the last few weeks.

That way, there’s no clear peg, but any bank that keeps access to at least twice as many treasuries as they’d need in reserves is solvent.)

30. September 2019 at 19:03

Scott, any guesses on why the unemployment rate has gone down so much in quite a few countries? After creeping up higher and higher which each recession since the 1970s or so.

Germany has the convenient explanation of their labour market reforms about 2005. But eg UK and US didn’t have those.

30. September 2019 at 23:41

What “slowdown in UK investment”? According to the first chart above, the slowdown is barely perceptable. Or perhaps I’ve misssed something.

1. October 2019 at 04:22

This is a very interesting post. I generally don’t explicitly decompose investment and consumption often enough in my mind when thinking about changes in real GDP and related changes in unemployment. Yet, it perhaps relates to a concept I have in which lower productivity growth can actually lead to lower unemployment, if consumption is strong enough.

1. October 2019 at 04:52

Nice post.

I think investment is tough to measure these days.

AMZN, GOOG, MSFT, FB have all created tremendous value, not just for themselves and owners, but for everyone and the capital draw or investment in how is is measured above is nothing. Yes the companies are pouring billions into capex these days but that’s for a separate business.

1. October 2019 at 05:36

Scott, whats your take on Farmer’s multiple equalibrium / animal spirits Keynes?

It’s obvious to me, though I assume you are loathe to admit it, we have a Trump Bump as recent proof.

I’ve always thought there is a synthesis between your Monetarist thinking and his Fiscal thinking.

So you just see shitty Obama Fiscal policy as some kind of shock that 5% NGDPLT can always overcome and keep LFP at 65% and U at 4%

Or do you recognize bad Fiscal policy will have a higher U or lower LFP at the same 5% NGDPLT?

—-

I have always like NGDPLT, bc once we stabilize MP and get the Fed turned into a computer as it were…

Then the mix of RDGP vs. Inflation is 100% on the Congress.

They get the credit for low inflation (high RGDP) and blame for high inflation (low RGDP)

1. October 2019 at 07:06

Jim, Even with zero reserves, cash would be important. So the monetary base would still be large. Right now we need more reserves because regulatory changes have led to an increased demand for reserves.

But yes, the absolute amount of reserves are not the question, it’s equating supply and demand at the target level of NGDP. If they can do so, then even a tiny amount of reserves is adequate.

Ben, You said:

“Scott Sumner advocates lower interest rates, trailing in the wake of Don Trump.”

You keep saying idiotic things. Do you just enjoy typing?

Matthias, I really don’t know. Perhaps companies such as Uber have reduced involuntary unemployment. Anyone with a car can now have a “job”. Maybe the internet has made job search easier. Maybe the economy has adjusted to the 1970s-1980s deindustrialization. Maybe unions are weaker. The minimum wage is pretty low in real terms.

Ralph, I should have said slowdown in investment growth.

Milljas, I agree.

Morgan, You said:

“shitty Obama Fiscal policy”

Obama’s fiscal policy was far less bad than Trump’s. The budget deficit has doubled to $1 trillion, at a time when the economy is strong.

1. October 2019 at 12:26

Scott wrote: “In 2014, the Japanese sales tax increase did sharply slow GDP growth for a quarter, but the labor market was almost entirely unaffected. The unemployment rate kept declining at the same rate, despite Keynesian scare stories about “recession”. (In contrast, Japanese unemployment rose sharply when NGDP fell in 2008-09.)”

1) Japan’s annual growth rate from April 1, 2014 when the consumption tax passed to March 31, 2015 was -0.1%, -0.9%, -0.5%, 0.0%.

The unemployment rate didn’t decline but was flat those months: 3.6, 3.6, 3.7, 3.7, 3.5, 3.5, 3.6, 3.4, 3.4, 3.6, 3.5, 3.4. In Japan, usually hours are cut instead of workers being laid off if there is a recession. Are you saying Japan didn’t have a recession then?

2) The Japanese unemployment rate did not rise “sharply” when GDP fell in late 2008/2009. Unemployment was at 3.9%/4.0% in 2008 and then slowly rose to 4.4% in Dec 2008, 4.6% in Feb 2009, 5.0% in April and peaked at 5.5% in July before falling to 5.2% in September, 5.0% in January 2010 and stayed at around 5.1% the rest of the year.

Here is a sharp increase in unemployment — the U.S. from 5.0% in Apr 2008 to 6.1% in Aug/Sep 2008 then 6.8% in Nov 2008, 7.3% in Dec 2008, 8.3% in Feb 2009, 9.4% in May 2009, 9.8% in Sep 2009.

1. October 2019 at 15:56

Hmmm, unemployment seems to react as a step function, at least it does when it is increasing. That is unemployment increases rapidly and it falls slowly.

This says to me that GDP has to contract, or get very close to zero growth, to trigger lay-offs and cause a jump in the unemployment rate.

So, a moderate slowing / contraction in investment (or other component in GDP for that matter) does not trigger the same sort of spike in unemployment that a larger contraction would trigger.

2. October 2019 at 14:41

Todd, In a technical sense, Japan has recessions every two or three years, as their trend growth is so low. But more realistically, 2001 and 2008 are their only meaningful recessions during this century. If you look at this graph you’ll see what I was talking about:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LRHUTTTTJPM156S

I believe my comments were consistent with the graph. If Japan has 3.6% unemployment on April 2014 and 3.4% unemployment on April 2015, then only in a narrow technical sense can that be viewed as a “recession”. Again, look at the graph.

BTW, 2008 saw the sharpest increase in Japanese unemployment since records began in 1960. Yes, the unemployment rate was not that bad, but it was bad relative to the very low natural rate in Japan.

3. October 2019 at 05:12

“If you look at this graph you’ll see what I was talking about:”

I did see the graph but unemployment in Japan was 3.6% in February 2014 and 3.7% in March right before the consumption tax went into effect and was at 3.6% in January 2015. It isn’t true that “The unemployment rate kept declining at the same rate.”

With four quarters of negative/zero growth with no change in unemployment, it looks like a mild recession to me.

3. October 2019 at 06:05

So you disagree the markets think Trump is good for the Economy?

Either way, I’m more concerned with the actual question in Economics:

Do you recognize bad Fiscal policy will have a higher U or lower LFP at the same 5% NGDPLT?