Research bleg

In this post I’m going to throw out a bunch of graphs, and ask for advice. First let me briefly discuss real wage cyclicality. Many of the early macroeconomists believed that real wages should be countercyclical. They held a sticky-wage theory of the business cycle. When prices fell sharply, nominal wages seemed to respond with a lag (even in 1921.) Thus deflation temporarily raised real wages, even as unemployment was rising.

Real wages were quite countercyclical between the wars, but after WWII many studies found them to be acyclical, or even procyclical. Most economists thought this was inconsistent with sticky wage models of the price level, and new Keynesian models ended up focusing on price stickiness and inflation targeting. Greg Mankiw and Ricardo Reis have a 2003 paper that shows that you generally want to target the stickiest price.

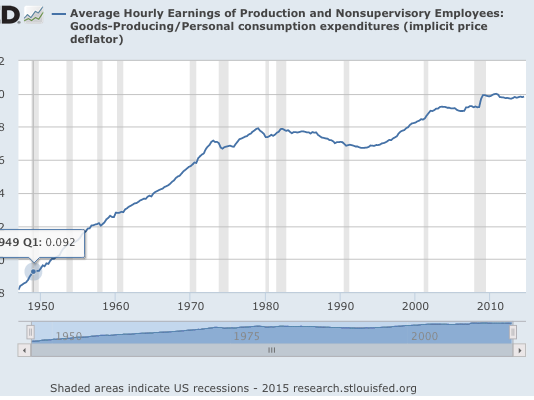

In 1989 Steve Silver and I published a paper in the JPE that showed real wages were somewhat countercyclical during demand shocks and strongly procyclical during supply shocks. We suggested that this finding was supportive of sticky wage models of the cycle. It even got cited in some intermediate macro texts (Mankiw’s textbook and also Bernanke’s.) But after a while it was ignored. In the graph below I show real wages during the post war years:

You can see why people didn’t find much cyclicality. And if you look closely you can also see some support for the paper I did with Steve Silver. When real wages rise during recessions (1981-82, 2001, 2008-09) it’s a demand-side recession. When they clearly fall (1974, 1980) it’s a supply-side recession. However there are some smaller demand-side recessions with almost no change in real wages.

Now let’s switch over to the “musical chairs” version of the sticky-wage model. In the real wage model discussed above, firms lay off workers because production is less profitable at higher real wages. In contrast, in the musical chair version of the sticky-wage model real wages don’t matter, what matters is revenue. When firms receive less revenue they have less income to pay wages, so they employ fewer workers. This would even apply to a socialist economy. Imagine all firms were owned by workers, who shared revenues. Also assume sticky nominal hourly wages. Then when revenues fell, hours worked at the firms would decline. That might mean a shorter workweek (as occurred in 2008-09 in Germany) or it might mean fewer workers (as occurred in 2008-09 in the US.)

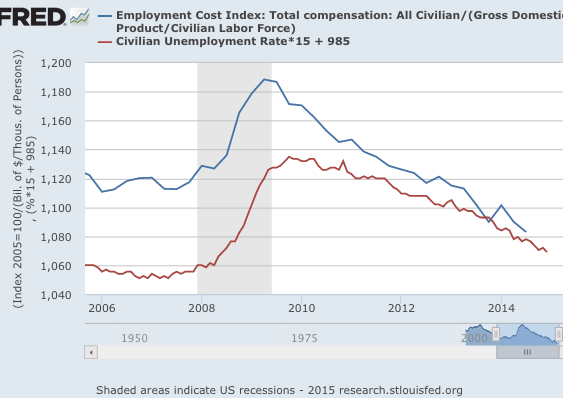

If we are looking to explain total hours worked, we might divide nominal wages by NGDP. If trying to explain the unemployment rate, it makes more sense to divide nominal wages by NGDP/Labor force. Previously I’ve showed that this cycle fits the musical chairs model quite well:

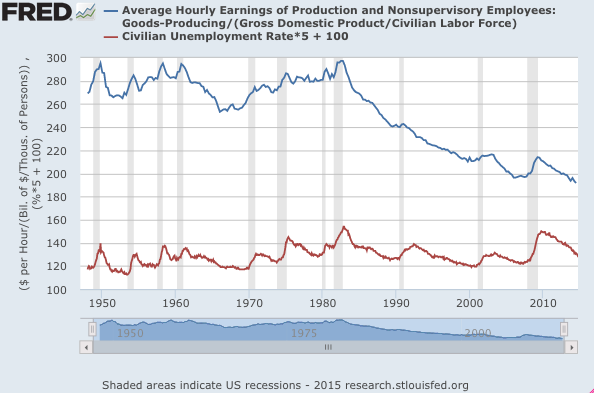

Unfortunately, we lack good wage data before 2006. For earlier business cycles, all I could find was wages in goods-producing industries:

Notice that the ratio of hourly wages to NGDP/Labor force has a level trend from the late 1940s to 1982, and then plunges by a third. That could reflect many factors, such as a change in hours worked per worker, but I think it more likely reflects three other factors:

1. More fringe benefits (good for workers)

2. Smaller share of NGDP going to workers (bad for workers)

3. More inequality within labor income (bad for non-managerial factory workers)

But what really impressed me is the strong correlation between wages/(NGDP/LF) and the unemployment rate. And by the way, even if you just used W/NGDP, you’d still see a strong correlation, as labor force changes are fairly “smooth.” But there would be even more trend issues to deal with. In my view, the weakest correlation appears to occur during the 1991 recession. But even there you see a brief flattening of what had been a steep fall in W/(NGDP/LF) during the 1980s and 1990s.

Here’s one question. How would you test for a correlation? I suppose you could compute changes in W/(NGDP/LF) minus a ten year moving average of the same variable, and correlate that with change in unemployment. Just eyeballing the graphs, I’d expect a reasonably close fit, even for 1990-91.

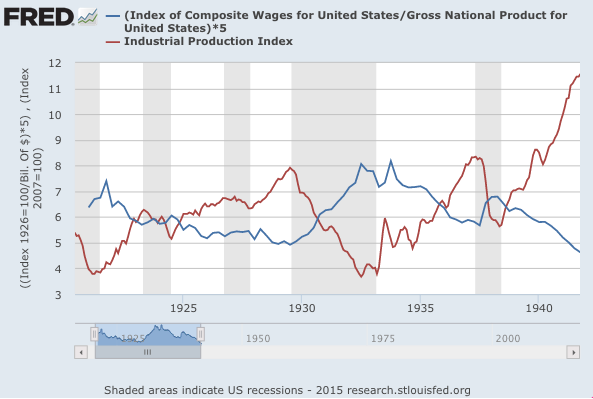

I know what you are thinking, how about the interwar years? I could not find unemployment data, so I used industrial production. Unfortunately that makes eyeballing the graph tougher as the predicted correlation is negative. Also, the NGNP data for 1921 at the St. Louis Fred is total crap. If someone over there is reading this, please replace your prewar NGDP estimates with Balke/Gordon, which is far superior, and goes back even further.

With the Balke/Gordon data, even 1920-21 would be a nice fit. But you can see the W/NGDP ratio rise in 1929-33 and 1937-38 as IP falls sharply.

With the Balke/Gordon data, even 1920-21 would be a nice fit. But you can see the W/NGDP ratio rise in 1929-33 and 1937-38 as IP falls sharply.

PS. I was a bit surprised by the real wage series. The fall in real wages from 1978 to 1993 didn’t surprise me—the rust belt took a toll on factory wages. But the uptrend after 1993 was a bit better than I had expected, given all the gloomy articles on real wage growth.

Tags:

31. January 2015 at 15:47

For the first chart, consider what happened to real wages after Nixon closed the gold window, effectively converting the monetary system into full fiat.

Real wages cannot keep up with inflation. Sticky wages.

31. January 2015 at 19:46

Sumner makes numerous errors in this post, let me highlight a few…and good post by MF.

First, the Sumner et al. paper (gated, so just from the abstract) is flawed for the following reasons: (1) it is data mining, note that it is contradicted by Bils, Geary and Kennan, and Neftci (2) it is subjective; the term ‘dominated by’ is apparently used to term whether a period is characterized by shifts in AS or AD. But in practice, both AS and AD will both change simultaneously, so it’s not at all clear how the authors would determine whether a period is “dominated by” either AS or AD.

Without Sumner supplying an ungated version of the paper–which perhaps did not get more attention from the economics community because it did not merit more attention–I cannot tell more.

Second, Sumner et al refers to ‘shocks’ yet Sumner in this post refers to long periods of time “from the late 1940s to 1982”. Is Sumner implying that his paper applies not just to ‘shocks’ (sudden recessions) but for all periods of time? That contradicts the paper.

Finally, Sumner asks the wrong question: “How would you test for a correlation?” should read ‘WHY would you test for a correlation?’ Even random data can be teased to find a pattern, even a nice sine wave, as is well known. Why would anybody do data mining to show that, e.g., yes, NGDP is coincident and correlated with real GDP? This goes to the heart of what confuses Sumner in all his theorizing–he fails to see two things: (1) real GDP drives nominal GDP, not the other way around, and, (2) the Fed, long term and often short term, follows the market, it does not ‘steer’ the market.

31. January 2015 at 20:49

Peanut gallery morons in full effect above me. MF and super mega genius Ray Lopez out in force. Anyway…

Interesting thoughts Scott, thanks for posting. One way to take a look might be through some kind of decompositional approach, rather than just examining the pairwise correlations. Something conceptually similar to the Oaxaca decomposition, although the methodology would need to be adjusted. In theory you could get some measure of the variation in the unemployment rate attributable to observable changes in nominal wages, while controlling for labour force participation and any other variable you might care for. Of course, all the usual caveats of working with a single time series would apply.

31. January 2015 at 22:18

OT: http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/the-blogger-who-saved-the-economy/262394/#disqus_thread

“We’ll stop short of saying that Sumner’s blog is worth tens of billions of dollars, although the full value of smart monetary policy is probably in the trillions of dollars.”

LOL, if Sumner saved the world, I just sculpted a masterpiece this morning. Want some Kool-Aid with that?

Truth is, the US Fed increased their net assets from almost $1T in mid 2008 to $4.5T today, and in stages: 1T added in late 2008, 0.5T added from 2009 to 2011 (with Mortgage-backed securities replacing other bailout related paper that was retired), 0.5T added from 2011 to 2013, and, most impressively, 1.5T added from Jan. 2013 to the end of this year. This last part was exactly when the government fiscal ‘sequestering’ was, so if you were Sumner you could argue (and he does) that a decrease in fiscal policy was offset by an increase in monetary policy. But if you do so, you have to ask yourself: if that theory is true, what happens when Fed balance sheet expansion ends? Do we go back to the levels of the Great Recession? Or so we expand the balance sheet forever to keep that from happening? When does this madness end? Contrary to Sumner’s silence to the rest of my questions, that’s a question I rather NOT get an answer to, as I’m afraid of our World Saver’s answer.

@Ben J – Oaxaca decomposition says our brainiac. It’s used as a way to guess, akin to an Excel what-if analysis, whether there’s labor discrimination. Perfect, an indirect approach for a hand-waver like Ben J… want some blue corn tacos with dat?

1. February 2015 at 03:31

Hah. Ray, did you Wikipedia that?

1. February 2015 at 05:41

If I read the second chart correctly, the employment cost index has been in steady decline for four or five years.

The Fed is worried about inflation? From where?

1. February 2015 at 06:26

Ray, Thanks for that critique of a paper you’ve never read.

Thanks Ben.

1. February 2015 at 06:27

Ray, You said:

“real GDP drives nominal GDP”

Thanks for explaining Zimbabwe.

1. February 2015 at 07:04

@Sumner – zing! You are good with one liners, but that’s more suitable for night club standup comedy that educating the masses about your NGDPLT framework.

Nominal GDP = Real GDP + Inflation. Hence if real GDP increases, so will nominal GDP, even with zero inflation. By contrast, if you have 100% inflation but zero real GDP, your nominal GDP will be up double in one year but the only thing you’ll have to show for it is inflation. What am I missing?

1. February 2015 at 07:19

Ray,

You are missing a fundamental understanding of real and nominal variables.

1. February 2015 at 07:51

And a portion of your brain. We’re you dropped on your head as a child?

Real GDP CAN increase without any inflation. It’s called supply side or productivity deflation. If nominal GDP rises at 3% per year and prices fall by 3%, real GDP rises by 6%.

You have a wrongheaded notion of what nominal GDP is all about. It’s a measure of MV of monetary velocity. Of consumption investment and government spending minus net exports. That’s the “real” number. It measures money changing hands in a given quarter or year.

In contrast depending on what price index you use, you can arrive at different figures. When you are trying to calculate “real GDP”

Sumner has discussed all this. Why don’t you educate yourself before pontificating on subjects you know nothing about?

1. February 2015 at 08:04

Where can i buy your book “The Midas Paradox: A New Look at the Great Depression and Economic Instability”?

1. February 2015 at 08:10

It is interesting thinking about how little real wages increased (or decreased) during the Reagan administration and it is something hardly anybody thinks about. So why do people not think about the wage stagnation from 78 – 93.

1) The big change during the era was the 2 income family which made the household income increase.

2) Why did 1990s go up? Two reasons: 1) This country was the first internet adapters. 2) The 1970s Baby Bust slowed down the supply of workers.

3) The early 1990s was the first “slacker generation” which saw a big fall in younger generation wages. Graduating college after 1990 most graduates spend several years over-qualified for a position with lower wages.

1. February 2015 at 08:12

“@Sumner – zing! You are good with one liners”

Ray.. you are still ahead by a field goal, with your “sculpted a masterpiece this morning” That made me laugh..

1. February 2015 at 08:21

Jacob, It’s not out yet.

Ray, You said:

“What am I missing?”

Nothing, you are a kind of perfection. I would not change anything.

You said:

“Hence if real GDP increases, so will nominal GDP,”

This is from the man who was lecturing me about the “good deflation” of the 1800s, just a few weeks back. Hence if real GDP increases, prices will fall. Hence if Ray says X one week, he will say “not X’ the next.

1. February 2015 at 10:18

@Ray Lopez: “Nominal GDP = Real GDP + Inflation. Hence if real GDP increases, so will nominal GDP” False. Can your super mega IQ not handle middle-school algebra? Since inflation is unconstrained, if real GDP goes up, nominal GDP might go up, stay the same, or go down. Any of those things could happen (via changes in inflation). This appears to be, in fact, the fundamental flaw in your failed understanding of macroeconomics.

“What am I missing?” I have a truly remarkable answer to your question, which alas the margin of this blog comment is too small to contain.

1. February 2015 at 10:29

Scott, off-topic, but I was reading about inverted yield curves and how they prove to be good indicators of forthcoming Recessions. First of all, do you agree that inverted yield curves can be used to predict Recessions? And, secondly, I read that during these inverted yield curves markets expect inflation to be low; is it also possible that such curves are actually a signal of inadequately tight monetary policy, in the same way weak nGDP growth or high real interest rates could be?

1. February 2015 at 11:58

Ray –

“Nominal GDP = Real GDP + Inflation. Hence if real GDP increases, so will nominal GDP, even with zero inflation. By contrast, if you have 100% inflation but zero real GDP, your nominal GDP will be up double in one year but the only thing you’ll have to show for it is inflation. What am I missing?”

Assuming you’re really seeking an answer and not just trolling, I’ll try to explain. Your formulation “Nominal GDP = Real GDP + Inflation”, while algebraically correct is misleading as to which variables are derived from which. Better to state it this way:

RGDP = NGDP – inflation.

RGDP is calculated from NGDP, not the other way around. First you calculate NGDP, then you adjust it by some price index that you think is relevant – usually CPI or PCE, but it could be hours of labor, or any price – I’ve even seen some gold bugs convert NGDP into ounces of gold. If you’re talking about an RGDP growth rate, you adjust each year into the common price unit first and then calculate the percentage difference.

After you understand that, it’s easy to see that if you target NGDP to grow at an geometric mean of 5% per year, that you are not trying to control RGDP and add some level of inflation on top of it. You are simply tying your dollar to NGDP and letting RGDP be whatever it comes to after you subtract your estimate of inflation (or add deflation).

1. February 2015 at 13:30

Negation:

I agree with your presumption that when using algebraic equations in economics, strict adherence to traditional rules of mathematical logic, such as Peano or ZF axioms, can lead to misunderstandings between people who have particular ideas in mind.

For

NGDP = RGDP + Inflation

According to the traditional ZF axioms, it is “equivalent” to

RGDP = NGDP – Inflation.

As you point out however, only one of these is useful in conveying the idea that RGDP is an dependent variable associated with NGDP and Inflation as independent variables. That RGDP is “calculated” by way of observing NGDP and observing Inflation and taking the difference.

Unfortunately even your approach suffers from problems as well. For one thing, NGDP and Inflation are not elements in the same set, as it were. Total spending on final products on the one hand and prices on the other, cannot be added, subtracted, multiplied or divided.

Consider. If last year NGDP was $10 trillion, and prices were an index of 100, then what is RGDP? The question cannot be answered.

Now you might be thinking that what RGDP = NGDP – Inflation really says is that if NGDP rises by 5%, and Inflation rises by 3%, then RGDP is “calculated” as rising 2%. The equation is a method for enabling us to determine how much real production, RGDP, increased or decreased. Yet still there is a big problem. For as you alluded to, we have to treat price inflation as an independent variable. We have to guesstimate, so to speak, at what Inflation is, and then along with NGDP, we can calculate RGDP.

The problem of course is that price inflation itself can only be calculated by way of RGDP and NGDP. We cannot know that prices rose 3% unless we know what happened to production and NGDP. This is because prices ARE a function of supply and demand. Supply in this case is RGDP, and demand is NGDP.

In other words, if you claim to have estimated that (price) Inflation was 3% last year, what you have done is already having estimated a value for the ratio of NGDP/RGDP. If you say prices rose 3%, what you are also saying is that the ratio NGDP/RGDP rose 3%. NGDP is not actually an independent variable in your version of the equality.

What you are really saying is this:

RGDP = NGDP – [NGDP/RGDP].

This equation is of course indeterminate. One equation with two unknowns.

The truth is that equations and traditional Peano or ZF axiomatic rules do not work for grounding economic theory.

NGDP is inexorably intertwined with RGDP and Inflation. These concepts cannot be divorced from each other and presented using inequalities without leading to the very kinds of problems that both you and Ray have fallen prey.

1. February 2015 at 13:42

Collins:

“It is interesting thinking about how little real wages increased (or decreased) during the Reagan administration and it is something hardly anybody thinks about. So why do people not think about the wage stagnation from 78 – 93.”

Obviously the reason is due to reasons other than the data itself, exactly like you are not mentioning the real wage growth rate reduction that clearly began earlier than 1978, despite the fact that that is what the data in the first chart shows. If you naively extend the trend line with a starting point at 1950, then the deviation away from previously steady rising real wages took place starting around 1973. The “kink” is conspicuous.

1. February 2015 at 14:43

@MF: “price inflation itself can only be calculated by way of RGDP and NGDP” Not true at all. You can estimate inflation by looking only at a representative sample of goods, and looking only at individual prices of those goods (i.e., ignoring quantities and total spending). It’s simply false that you need to assemble NGDP (or RGDP) in order to estimate inflation.

“NGDP is inexorably intertwined with RGDP and Inflation.” Also false. You can simply add up all the dollar amounts in all transactions on final goods, to calculate NGDP. It requires no knowledge at all (not even implicit knowledge) of either RGDP or inflation.

1. February 2015 at 15:29

Major –

Don is correct. The BLS publishes the CPI without calculating NGDP or RGDP. It’s just the price of a basket of goods. Think of this way – it is possible to calculate NGDP growth without any knowledge of RGDP or inflation. It is possible to calculate inflation without any knowledge of RGDP or NGDP. It is not possible to calculate RGDP growth without knowledge of both NGDP and inflation.

1. February 2015 at 16:51

Don and Negation:

If you consider only a particular subset of goods, which is a subset of RGDP, then what you would be doing by calculating “prices” here would require here is the total of spending on those particular goods and the supply of those particular goods. That is, you would need a subset of NGDP and a subset of RGDP.

The same requirement is present here. In order to “estimate” prices at any level, RGDP or that which makes up a particular basket of goods, you are calculating the ratio of pNGDP/qRGDP, where 0<p<1 and 0<q<1.

The way the BLS calculates the CPI is by weighting the price inflation of each good in the basket. The weighting is a reflection of the fact that they rely on the total spending on the goods in question.

One cannot calculate prices without demand (spending in the classical sense) and supply.

Even for a single good, such as a PC, in order to “calculate” the price, you need to know, and are relying upon, total spending on that one good, and the supply, which is one PC. The price here is the ratio of “nominal gross domestic PC” and “real gross domestic PC”. These are of the same family of NGDP and RGDP. NGDP just adds each individual expenditure.

You cannot know prices without also knowing both the spending variable and the real variable. If you assert that you have calculated or estimated “prices” without conscious reliance on NGDP or RGDP, then what you have actually done is estimated the ratio of NGDP/RGDP whether you realized it or not.

Remember, prices are the ratio of spending to supply. If you do not know either spending or supply or both, then your thoughts on price are purely hypothetical, and whose accuracy is measured by how accurate your implied estimates for NGDP and RGDP are.

1. February 2015 at 17:06

Think of it this way, Don and Negation. Suppose I estimated aggregate price level to be a value which I denote by giving it an index of 100, and I did not even consider NGDP or RGDP.

Suppose that the price level measured by NGDP/RGDP is a value that is given an index as well. Suppose that if it is higher than my estimate, then it is given an index of 105, and if lower, 95. In other words, my estimate is the base index, which of course does not suggest my estimate is more or less accurate. It is just a baseline.

Now suppose someone then went out and measured NGDP and RGDP, without taking into account price levels. Suppose their measurements are accurate. Suppose they measure the ratio of NGDP and RGDP to be higher than my estimate of prices that did not consciously take into account NGDP or RGDP.

Wouldn’t my price level estimate be wrong because it contradicts the price level as calculated by NGDP/RGDP? To me my estimate must mathematically be wrong, because prices are defined as the ratio of spending to goods.

1. February 2015 at 17:27

Don:

More specifically now, you wrote:

“You can estimate inflation by looking only at a representative sample of goods, and looking only at individual prices of those goods (i.e., ignoring quantities and total spending). It’s simply false that you need to assemble NGDP (or RGDP) in order to estimate inflation.”

Right, but that would only be an estimate, and its accuracy would be more or less accurate depending on what NGDP actually is and what RGDP actually is. If you only look at say tons of iron, or a basket of goods, and you observe the prices to have risen 2%, then what you have done is added up each price, which is of course dependent on knowing what total spending is on those goods. If for example total spending is $10 billion, but in your additions of prices of tons of iron sold, it adds up to only $9 billion, then you know you have missed some prices and sales of iron.

Adding up individual prices IS forming an NGDP estimate. If you stop short of adding up ALL prices out of convenience or necessity, and you infer that what happened to spending and supply in your observed basket is mirrored by what happened in the aggregate, then your estimate of aggregate prices in this way will live or die depending on what NGDP actually is and what RGDP actually is.

This is what I meant by saying that calculating aggregate prices, or estimating aggregate prices, is whether you like it or not calculations or estimations of NGDP and RGDP.

“You can simply add up all the dollar amounts in all transactions on final goods, to calculate NGDP. It requires no knowledge at all (not even implicit knowledge) of either RGDP or inflation.”

I think you did not address my challenge. I said you need to know NGDP and RGDP in order to know prices. And what you just said there is perfectly consistent with that. You said to add up all prices. Well, how do you know when to stop adding prices? You know when to stop when you have reached NGDP and RGDP!

——————

Negation, you wrote:

“The BLS publishes the CPI without calculating NGDP or RGDP.”

Yes but then prices here are not aggregate prices. They are the prices of a specific basket of goods that are constrained to a subset of NGDP and a subset of RGDP which you are fully dependent on.

“It’s just the price of a basket of goods. Think of this way – it is possible to calculate NGDP growth without any knowledge of RGDP or inflation.”

That is impossible. If you claimed to have calculated NGDP, then by definition you have included a consideration of all goods in GDP, i.e. RGDP. If you tell me “Major I have added up all expenditures and the total, NGDP, is $10 trillion”, then how do you know you have added up ALL the purchases of goods that are included in GDP? How do you know you’re not missing any expenditures? You would have to know total supply of course!

“It is possible to calculate inflation without any knowledge of RGDP or NGDP. It is not possible to calculate RGDP growth without knowledge of both NGDP and inflation.”

That is not correct. You cannot claim to have calculated aggregate price inflation without tacitly claiming to have considered final goods spending and final goods supply.

If you are only considering a basket of goods, then what you are doing is implying an estimate for NGDP and RGDP. For imagine calculating the price inflation for a basket of goods such as the CPI. If you then were shown that there is a whole other portion of the economy whose prices and supply changed differently than the goods in the basket, then you would of course be compelled to admit that the further away the price changes of those non-basket goods are, the less accurate your estimate of prices. All this of course means that your estimate of prices is actually made more or less accurate in reality by what actually happened to NGDP and RGDP.

1. February 2015 at 19:36

@Everybody, including Sumner:

I said: “Real GDP drives nominal GDP” – and that is 100% consistent with what you are saying, with the exception of MF, who presents the Austrian view, as I explain below. Again, inflation plus real GDP equals nominal GDP. That’s logic, not Zimbabwe. If inflation is negative, then nominal GDP will be less than real GDP, but the point being is that nominal GDP has no influence over (is not driving) real GDP. If you concede that, monetarist, YOU LOSE (DonG loses, again). Because Monetarists believe in ‘money illusion’, that is, if velocity is great and nominal GDP is great, somehow, magically, it will result in people spending more in the short term that magically influences long term real GDP. Bunkum.

@ everybody criticizing MF: MF is right in his own way. He is an Austrian. Austrians do not believe in AD/AS. Hence there’s no such thing as an “aggregate” price level in Austrian logic, hence, RGDP = NGDP – [NGDP/RGDP] is 100% correct. To a degree, Austrians are ahead of everybody else. The assumptions of AD/AS were made for a pre-computer age to make the math easier, and the linear blackboard equations simpler to solve. I don’t have space in this crummy forum (Sumner: please get Simple Machines Forum software–it would encourage your readers like me to post better and more often…now I know he won’t do it, lol) to explain, but the Austrians are correct because anytime you change one supply /demand curve in an economy you simultaneously change all the others. I, Pencil, taken to the Nth degree, butterfly wings causing hurricanes and all that. But it’s impossible (or very hard) to model even approximately without a supercomputer, hence, Samuelson’s continuous variable calculus and simplifications like ‘aggregate’ data, the Cobb-Douglass production function, and the like.

@Negation- thanks. Consider however how Sumner’s NGDPLT framework results in a smaller increase in the money supply than targeting merely inflation–is this what Sumner wants? Suppose inflation is -4% a year. Suppose the futures market for NGDP says it will be 1%. So real GDP will be 5% (5-4=1) yet the Fed will only increase the money supply by 1%? I don’t think Sumner would approve (hard to say, as he’s so vague). I think Sumner would like to ‘peg’ or arbitrarily target a number, somehow linked to a futures market yet to be invented, like say “6% NGDP growth” and shoot for that. Monetarists like Sumner like Zimbabwe, like inflation, hate hard money. Thank you.

1. February 2015 at 20:06

Ray, why would you lie that monetarist like Zimbabwe? Are you comfortable lying about other people’s views?

1. February 2015 at 21:03

Spending does not drive production, and production does not drive spending. Human goal seeking drives both spending and production.

Increases in spending do not increase production, and increases in production do not increase spending. Human goal seeking increases both spending and production.

Reductions in spending do not reduce production, and reductions in production do not reduce spending. Human goal seeking reduces both spending and production.

If my desired wage rate is too high given the demand for labor, thus resulting in my unemployment, central banks printing money is not going to cause my employment. I will just ask for an even higher wage rate thus keep myself unemployed, for it is in existing money conditions and production conditions that I set my desired wage rate. If the conditions change, then there is no reason to believe my goals will remain the same.

If MMs tell me that more inflation will turn my formerly excessive desired wage rate into a realistic one, and they assume I will be able to understand that the intent here is to reduce the real value of my desired wage through price inflation, then it is absurd, false, and a total lie to believe that I would be unwilling to reduce my desired wage rate even if I knew prices would not rise because of an absence of central bank inflation.

What MMs arereall referring to when they talk about “money illusion” is there own illusion of the reasons why I am unwilling to reduce my desired wage rate given I expected higher prices, higher spending, and a higher nominal demand for labor. MMs have reversed cause and effect. The cause for why I am not willing to reduce my wage rate is inflation. Inflation is no cure for that!

When MMs talk of sticky wages, and central bank inflation as a means to causing employment, what they are really referring to whether they like it or not, is the unbelievably trivial point that monetary inflation encourages people to set prices as sticky downwards.

Temporary monetary fluctuations that might for a time consist of falling spending, is going to instantly convince the entire population to haphazardly reduce all prices and all rates in lockstep. Not when for the last 100 years central banks have generated the appearance that rising prices are akin to an inexorable law of nature that central banks can only at best “fight” or “react to”. Economics is a specialized field of inquiry, and economists the world over have done a piss poor job of educating the man on the street. Economics has become (or maybe always was) an ivory tower, isolated and barricaded discipline that has metasticized into an inner clique of extreme mathematical laden jargon that is incomprehensible to the layman. Not to mention the ideologue economists who have encouraged the myth that price inflation is a capitalist ploy.

If instead the last 100 years consisted of free market mo ey that just so happened to result in productivity based price deflation, and people learned and expected gradually falling prices as akin to a law of nature, then wage rates and prices might very well be sticky upwards. During periods of temporary “abnormal” spending increases, it is quite possible for shortages to arise, since even though spending has increased, people still expect prices to fall even though the market clearing efficient outcome would be for prices to temporarily rise in the short run. And if we observe multiple such periods of temporary spending increases and temporary shortages, would there be doppelganger MMs there to advocate for centralizing the monetary system so as to eliminate those pesky periods of temporary abnormal spending increases so that the shortages do not occur?

MM = zero trust in the market and total trust in socialist institutions…as long as the socialist institution follows the rules set out by the MMs of course.

1. February 2015 at 21:10

@Ray Lopez: “Real GDP drives nominal GDP” No.

“nominal GDP has no influence over real GDP” No.

“no influence over [is the same as] (is not driving)” No, these are different concepts.

“nominal GDP is not driving real GDP” Ah! Finally, one we can all agree on.

NGDP and RGDP are two separate, independent concepts. Their levels can move at different rates, and even in different directions. In many ways, they are mostly independent. However: there are a few special cases, where shocks to one have some influence (without completely “driving”) the other. You seem to think that the only possibilities are the one of the concepts must be some kind of “primary”, while the other is just a trivial consequence. But it doesn’t work like that. NGDP and RGDP are independent things, with complex occasional interactions between them.

1. February 2015 at 21:19

@MF: “If my desired wage rate is too high given the demand for labor, thus resulting in my unemployment” You have the theory wrong. That’s not why tight money + sticky wages cause unemployment. (Hint: it’s about the wage rates of the people who remain employed, not the “too high” wage demands of those who are unemployed.)

“The cause for why I am not willing to reduce my wage rate is inflation.” You’ve stated this claim many many times. And there’s a chance it might even be true. But you’ve offered no justification for it, and it seems highly unlikely, so the prudent course is for us not to believe your implausible claim.

1. February 2015 at 23:12

Don Geddis:

“That’s not why tight money + sticky wages cause unemployment. (Hint: it’s about the wage rates of the people who remain employed, not the “too high” wage demands of those who are unemployed.)”

Well that is clearly wrong, because if it were constrained only to those with jobs, then it would not constitute an explanation for why tight money leads to unemployment.

No, sticky wage theory does not exclude those without jobs. It includes them. Sticky wage theory says that wage rates do not adjust immediately in line with nominal demand for labor changes, specifically, downward changes.

If instead the wage rate bids and asks for the unemployed fell sufficiently in line with the fall in nominal demand for labor, then unemployment would not result. Sticky wage theory says that unemployment results because wage rate bids and asks do not sufficiently fall immediately with a fall in nominal demand.

It makes no sense to exclude unemployment from a theory that purports to explain one significant cause of its existence!

“The cause for why I am not willing to reduce my wage rate is inflation.”

“You’ve stated this claim many many times. And there’s a chance it might even be true. But you’ve offered no justification for it, and it seems highly unlikely, so the prudent course is for us not to believe your implausible claim.”

In other words, stick your fingers in your ears or cover your hands over your eyes, say “unlikely”, “no justificstion”, and go on continuing what you want to believe, or perhaps what you need to believe in order to justify your intellectual investment.

The justification for someone not reducing their wage rate asking price given a temporary reduction in demand, and prices expected to rise is straightforward enough. If I wait it out a little bit, and live off my savings, then I might find a job that does pay the wage rate I ask and thus secure the income derived standard of living I expect to have with my skills/experience/productivity, minus the loss in investment income due to decreased savings, which is super low now anyway with near zero interest rates. If I bite the bullet now, and ask a lower rate, then I am assured to “lock in”, at least temporarily, a lower standard of living given my price expectations. Given welfare, and assuming my asking rate is at the minimum wage set by law, then my incentive to not reduce my asking rate is all the more incentivized.

Noe if on the other hand I expected prices to fall, then in order for me to secure the same standard of living as the above, I would be able to ask a lower rate in the present. What I would have to worry about is that my wage rate declines on average slower than prices. I would be less inclined to insist on at least the same wage rate I have historically earned, because I would be used to paying lower price for goods. Yes, I would still be faced with the option of holding out for a little bit, so that I might find a job that pays the same wage as before. But I would not be locking in a comoarative loss by accepting a lower rate today, because prices are now expected to fall instead of rise. I could maintain the same or higher standard of living over time even by asking, and landing, a lower rate than before.

I see a total lack of imagination on your part for why someone would be less willing to accept a lower wage rate given prices are rising instead of falling, and all the imagination in the world for how they would think of a myriad of things that would constitute a “money illusion.”. Hmmm…I wonder why that is…

2. February 2015 at 02:18

Hi Scott,

How about just applying the Hodrick-Prescott filter and computing the correlation and second moments? That’s the go-to in the RBC literature.

2. February 2015 at 03:27

Here are the detrended series. Smoothing parameter of 1600, since the GDP data was only quarterly.

http://s14.postimg.org/lyqyb0lgh/Hourly_Earings_Unemployment_Rate.png

Raw correlation is 0.7996

Unemployment is 77 times more volatile than Hourly Earnings / (GDP / CLF), which should be expected as unemployment is 70 times more volatile than GDP. So I’ve stuck scales of each series on a different side for comparison.

2. February 2015 at 04:57

@Don Geddis – cite please? You sound full of it. Here’s my cite for saying nominal and real GDP are connected by nothing more than the inflation rate: http://economics.about.com/cs/macrohelp/a/nominal_vs_real.htm

It’s not rocket science Don. It’s just simple arithmetic: NGDP = Real GDP + inflation. You’re probably confused since you believe in sticky wages and money illusion, hence, you believe inflation should be positive at all times. In that case, Nominal GDP > Real GDP due to inflation. But the real GDP is the only parameter of interest to society. If real GDP is going down, there’s misery, even if NGDP is at Zimbabwe record levels. Conversely and equivalently, if real GDP is going up, there’s joy even if nominal GDP is negative due to deflation.

2. February 2015 at 05:38

Wages (and debts, and other things) are sticky. End of story.

Anybody who argues otherwise is a moron and/or a liar.

2. February 2015 at 07:15

You might find the collection of graphs on antonio fatas’ blog interesting: http://fatasmihov.blogspot.com.br/2015/02/which-country-managed-great-recession.html

I was particularly struck by how Spain managed the largest increase in GDP per worker since 2008. The reason is clear: In a rational economy you fire your least productive people first, so a decline in employment puts upward pressure on wages per worker, even if there is no change in anyone’s wages (except those who get fired).

On the other hand, Spain is near the bottom on GDP per working age population, as its unemployment rate is so high. I think its likely that a lot of the rise in real wages in demand side recessions is really a compositional effect, as in Spain, which obscures any sticky wage effect.

As to differentiation between supply side and demand side recessions, this is really just the fact that the former are characterised by high inflation, and the latter by low inflation. Thus, there is much stronger downwards pressure on the real wage series during supply side than demand side recessions, but since this is “supply side inflation”, it says little about real wages in the sense that they are important for macroeconomics/unemployment. Its just a temporary change in the series.

There also might be different compositional effects, e.g. unemployment concentrated in the supply sector rather than concentrated on the low paid.

In order to answer your questions, you really need to strip out these compositional effects, and choose a measure of inflation which strips out the price changes in the supply side commodity that is the cause of the recession (Normally Oil).

If we could do those things, then we would have some data series that might shed some light on this problem.

2. February 2015 at 07:27

@Daniel–*you* are a liar. We have repeatedly asked you for a citation for sticky wages, prices, debts, and all you do is cite a discredited Wikipedia link that mentions the discredited Douglas-Cobb production function as a reference. Get off this board you fraud! Sticky prices, outside of laboratory and theoretical models, do not exist. Sticky wages arguably might exist for large multi-national corporations (or maybe not, as these days these corporations hire cheap foreign labor and outsource) but from a Coase theorem point of view they matter not for GDP. For unemployment purposes sticky wages might arguably matter, but that’s not of much concern to society, which is largely not employed by such large corporations. For GDP, sticky wages, if they exist at all, matter not a wit, or matter but a scintilla.

2. February 2015 at 07:37

Ray,

Thank you for proving my point.

2. February 2015 at 08:17

MF.. How funny would it be if they were to get their way, force cash into spending, and then watch AAA credit rated companies lose their ratings. (not saying that would happen) How many people making these suggestions understand balance sheets? Now they want to change a CFO’s ability to manage his coverage ratios. Funny to read, but nonetheless Insane!

2. February 2015 at 08:21

MF,

The 1920s were a decade of falling prices and positive nominal growth. Yet that did not prevent sticky wages in the 1930s. (Yes government interfered, but your point was about psychology. A decade of falling prices didn’t prime workers for wage cuts. How long would it take? A century?)

From 1873 to 1896 prices fell.

Some of those years had positive growth. Others were in recession. During the recession years, unemployment rose before falling.

Your theory is bunkum

2. February 2015 at 08:37

@Ray Lopez: “You sound full of it. … NGDP = Real GDP + inflation” It’s sad that you don’t realize that nothing I said is in conflict with that equation.

“hence, you believe inflation should be positive at all times” Every time you try to imagine what you think other people believe, you aren’t even close. In fact, the opposite of your guesses is usually more accurate than what you actually assume. Why don’t you stop trying to guess what other people think? You’re not very good at it.

2. February 2015 at 08:48

You can try regressing changes in the two series (either absolute or percentage) but add a Markovian regime change that should pick up the weird flip flop in the relationship that happens around 90-91. Of course, then you will want to explain why the relationship might be different during that period.

Of course, if you really knew that then ideally you would find a metric for that and interact that in the regression.

2. February 2015 at 08:51

@MF: “If instead the wage rate bids and asks for the unemployed fell sufficiently in line with the fall in nominal demand for labor, then unemployment would not result. Sticky wage theory says that unemployment results because wage rate bids and asks do not sufficiently fall immediately with a fall in nominal demand.”

What if the market-clearing price for currently-unemployed labor, is below zero? Does it still make sense to “blame” the unemployed themselves, for having wage demands that are “too high”?

Your view of sticky wage theory, focusing on wage demands of the unemployed, is like looking only at the tip of the iceberg. There are far, far more workers who remain employed, than that tiny fraction that gets laid off during a recession. The huge bulk of the iceberg that appears to have completely escaped your notice, is that the real compensation of those (vastly greater number of) workers who remain employed, has suddenly skyrocketed during a tight-money recession.

In fact, it’s even worse. For many of the same reasons that employers don’t cut wages of current employees, they also generally won’t hire new workers at substantially lower salaries. A “two-class” workforce is bad for morale. So it’s often the case that the unemployed (in a tight-money recession) will not receive a job offer, no matter how low their wage demands are! Even a demand of zero will not result in a job offer.

So your idea, that “If my desired wage rate is too high given the demand for labor, thus resulting in my unemployment” just completely misses the whole point.

BTW: “I see a total lack of imagination on your part” Oh, I can imagine all sorts of things. But some of us then choose to take a second step afterwards, and try to verify whether there is any correlation between our imagination, and the behavior of the real world. You seem satisfied to just stop with the first step.

2. February 2015 at 08:51

Derive:

“MF.. How funny would it be if they were to get their way, force cash into spending, and then watch AAA credit rated companies lose their ratings. (not saying that would happen) How many people making these suggestions understand balance sheets? Now they want to change a CFO’s ability to manage his coverage ratios. Funny to read, but nonetheless Insane!”

Yes, it can definitely get amusing to read the insanity. But you’re talking about corporate finance and capital theory. MM is intentionally silent on these issues, no matter how destructive the MM ideology in practice is on them. What matters are macro variables hardly anyone in business cares about. Businessmen are on average too stupid to be able take NGDP seriously like they should.

—————–

“The 1920s were a decade of falling prices and positive nominal growth. Yet that did not prevent sticky wages in the 1930s. (Yes government interfered, but your point was about psychology. A decade of falling prices didn’t prime workers for wage cuts. How long would it take? A century?)”

LOL, so your argument consists of recognizing that government interfered with wages, but I am still wrong because wages did not fall sufficiently in an unhampered labor market?

There’s gumption, and then there is what you’re doing. It is off the charts shysterism.

We cannot observe workers across the board accepting lower wage rates when the government and certain large companies did everything they could to prevent falling wages out of a mistaken view that above market wage rates is the path to prosperity.

“From 1873 to 1896 prices fell.”

Falling prices is a necessary, not sufficient condition, for wage rates to fall in the way I described.

If the nominal demand for labor keeps rising, as it did throughout the late 19th century, then provided that increase is greater than the growth in supply of labor, there is no reason for wage rates to fall. It is not the case that falling prices ipso facto causes a fall in wage rates. Only that the psychology of resisting wage cuts out of expectations of rising prices, is absent.

“Some of those years had positive growth. Others were in recession. During the recession years, unemployment rose before falling.”

Falling without NGDPLT.

YOUR theory is “bunkum.”. I mean how hilarious an argument is it to point out thT the government interfered with wages thus preventing them from sufficiently falling during the early 1930s, and then claiming this proves wage stickiness. Wow. I mean I don’t even.

2. February 2015 at 09:08

In fact, it’s even worse. For many of the same reasons that employers don’t cut wages of current employees, they also generally won’t hire new workers at substantially lower salaries. A “two-class” workforce is bad for morale. ”

Fwiw, the auto companies have gone to a two-tier wage system. Another example of this in practice: Schools will hire younger teachers rather than older teachers who command high wagers.

If prices rise, companies can keep wages the same, thus real wages will fall.

If prices fall, then workers have a better chance of raising their real income.

2. February 2015 at 09:32

Don:

“What if the market-clearing price for currently-unemployed labor, is below zero? Does it still make sense to “blame” the unemployed themselves, for having wage demands that are “too high”?”

If you assume the market clearing price for labor is below zero, then you are assuming that employers are investing ZERO dollars in labor, and not only that, but they demand payment from workers for the privilege of receiving their labor services.

I always consider thought experiments and never dismiss them for being unrealistic, because they are useful tools to understand realistic scenarios, but I confess that I do not see how assuming employers everywhere suddenly demanding payment from their workers, thus bringing about your proposed scenario of negative market clearing wage rates, to be of use in understand realistic scenarios where the demand for labor has always been positive, above zero, thus implying positive market clearing wage rates.

“Your view of sticky wage theory, focusing on wage demands of the unemployed, is like looking only at the tip of the iceberg.”

Woah woah woah. I never said or implied that wages of those employed not falling has zero association with the unemployed. Of course there is a connection there. I agree with you there.

“There are far, far more workers who remain employed, than that tiny fraction that gets laid off during a recession. The huge bulk of the iceberg that appears to have completely escaped your notice, is that the real compensation of those (vastly greater number of) workers who remain employed, has suddenly skyrocketed during a tight-money recession.”

Right, in large part because of a persistent expectation of such “tight money” episodes being temporary! I don’t see how my main point is cast into doubt by the presence of bid and ask wage rates not instantly falling for both recently unemployed and recently employed. Psychology is not limited to the unemployed.

The reason why I “focused” on the bid and ask prices of the unemployed is not because I deny that those employed at above market clearing wage rates are in a sense “crowding out” the unemployed at their above market clearing bid and ask rates, but rather to drive the point home that what I said is a factor that should not go ignored. I would argue that unemployed wage rate bid and asks encompass the majority of problematic sticky wages, because when there is a tight money recession, the recently made unemployed are by the nature of the case those who bore the brunt of the effects of tight money, and thus to me it would seem that their wage rates would bear the brunt of the decline in a free market where the tight money was expected as permanent. I submit I see no widespread or frewuently possible reasons for why in a free market there would be a permanent decline in money and spending such that rational expectations leads to lower wage rates as the ideal solution for all parties. But I won’t rule out the possibility.

At any rate, telling me that the wage rates of those employed are sticky downwards, which I agree may have the effect of “crowding out” those unemployed given the bid and ask wage rates in the unemployed demographic being above market, I must say that we’re still talking about the wages of the unemployed being sticky and that if they fell sufficiently in response to the permanent tightened money going forward, consumers have shown us that it is those wage rates that should fall the most.

Tight money, what it is in reality, is not merely an aggregate decline. It is a complex relative series of declines. Those who are in the less valuable production lines, bear the brunt of consumers choosing money over goods. Crucial goods face less of a decline than so called luxury goods. Economists call these procyclical and countercyclical goods.

Imagine you being offered a 20% wage cut, and you accepted. Would you decrease your spending on EVERYTHING by 20%? Of course not! You might even INCREASE your spending on certain goods, like potatoes and Mac and cheese. What an aggregate decline in your spending tells producers is to reduce production in “these” goods, but not “those” goods. That generates a change in relative profitability, which redirects resources away from less valued goods to more valued goods.

That then makes certain employment opportunities relatively more lucrative. The US has experienced precisely this due to government having gutted the industrial sector with its large deficits and inflation that have decimated the industrial base of the country, combined with decades of hostile attacks on savings, and a focus on consumption as the driver of economic growth. Value is now predominantly in the service sectors, which is where a growing number of workers are able to find employable opportunities given the capital that remains.

“In fact, it’s even worse. For many of the same reasons that employers don’t cut wages of current employees, they also generally won’t hire new workers at substantially lower salaries. A “two-class” workforce is bad for morale.”

Zero wage rates are EVEN WORSE on morale. Please don’t set up artificial constructs and then distinguish wage cuts against that and then sit back and say that’s why we need inflation.

Two class system? Nonsense! The wage sector is a dynamic flux, a spectrum, not a crude two tier us versus them imaginary class war. You’re just introducing Marxian class warfare into the wage class and ignoring those thoughts and behaviors among the wage class that contradict that dystopian vision.

“So it’s often the case that the unemployed (in a tight-money recession) will not receive a job offer, no matter how low their wage demands are! Even a demand of zero will not result in a job offer.”

If the employers and wage earners expected a permanent reduction in prices and nominal demand for labor, and employers and workers alike expected tax financed welfare to be zero, then the desire to profit and the desire to eat, will tend to eliminate unemployment.

There is zero reason to believe employers will choose lower profits over higher profits, while workers choose starvation to working. All you are doing is claiming that in a free market, job and profit opportunities will be purposefully ignored by greedy businessmen and greedy workers, to the point where people die on the streets from their stupidity.

“So your idea, that “If my desired wage rate is too high given the demand for labor, thus resulting in my unemployment” just completely misses the whole point.”

No it doesn’t. It outright and explicitly REJECTS that point.

“BTW: “I see a total lack of imagination on your part” Oh, I can imagine all sorts of things.”

They happen to be dominated by visions of dystopia. Coincidence?

Every world tyrant was deep down terrified at the world. They a priori viewed the world as a battleground, a place of exile and perpetual hostility and strife. Just like you aepre doing.

“But some of us then choose to take a second step afterwards, and try to verify whether there is any correlation between our imagination, and the behavior of the real world. You seem satisfied to just stop with the first step.”

Oh ya, your claims are so very empirical. Imagining negative market clearing wage rates and people dying on the streets from this boogeyman moneyillusion. For pete’s sake dude, brighten the shit up. People are not as stupid as you a priori believe them to be. You see what you want to see in the real world. You want to see wage stickiness, so you ignore the wage rates that actually decline even during temporary periods of deflation. Empirical? Ha! More like sample and confirmation bias.

2. February 2015 at 09:33

Ashton,

I thought it was a very good series of questions. Since no one answered, remaining in my boundaries, I can answer the finance part and you should be able to deduce the answer to some of your other questions from that.

Inversion is an abnormal state for a market. It is, in most cases, a signal to pull supply (inventories) of inverted item forward and move demand (consumption) back in time.

In the case of interest rates it is essentially doing the same. The belief you are receiving a higher short term real interest rate, is changing incentive in t0 from consumption to saving, and moving preference for consumption back in time.

If you want your ice cream now, you have to be given incentive to wait until tomorrow. Offering you the choice between ice cream + money tomorrow, vs. an ice cream today tends to work.

2. February 2015 at 09:34

Sorry Charlie, forgot to include your name before I started quoting you.

2. February 2015 at 10:54

@DonG and others who think we have an output gap due to unemployment:

we don’t. It’s structural unemployment caused by demographics. Declining demographics means declining employment and lower GDP growth. There’s no output gap. 2% growth is the new 4%. See here: http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2015/02/demographics-and-gdp-2-is-new-4.html

Ergo there’s no room for expansionist monetary theory. Leave well enough alone.

2. February 2015 at 11:11

Ashton, They have some ability to predict turning points, but less than many people assume. It’s predictive ability has fallen in recent decades, it was very good from 1969 to 1982.

Yes, it can also reflect tight money.

Thanks Rob, I’ll look into that.

Thanks Phil, But an alternative (which I prefer) is to stop looking at real wages, and focus on W/NGDP.

Njnnja, That’s why I suggested subtracting the 10 year average of the rate of change from the actual rate of change—to avoid having to make ad hoc assumptions about regime changes.

Ray, You said:

“Austrians do not believe in AD/AS. Hence there’s no such thing as an “aggregate” price level in Austrian logic, hence, RGDP = NGDP – [NGDP/RGDP] is 100% correct.”

???????????????????????????????????????

But I do agree with the “Austrians” than the aggregate price level is not a very useful concept.

2. February 2015 at 11:28

There are some wonky things about correlating moving averages with each other. A more straightforward approach would be to take first-differences of both variables, verify stationarity, and regress one on the other controlling for 2nd- or 3rd-degree polynomials of time. Or you could always go cross-national…

2. February 2015 at 11:57

@Ray Lopez: “Declining demographics means declining employment” You constantly confuse what you imagine others think. Nobody was complaining about declining employment. The concern was high unemployment (e.g. 10+% in 2009). “Employment”, and “unemployment”, are different concepts. (Just like NGDP and RGDP, another pair of different concepts that you constantly confuse.)

Hint: just because words sound the same, and have similar spellings, doesn’t mean that the concepts they refer to are identical.

2. February 2015 at 12:04

(OFF TOPIC) Reading your posts about NGDP futures, it occurred to me that, while they may fulfill the purpose of providing a level for Central Banks to target, I suspect they would struggle to gain market traction because they lack any real purpose for ordinary people. A better solution, it seems to me, would be to issue NGDP-linked bonds, in the same vein as TIPS. You’d at least have dealers making markets which, in turn, would attract investor interest and set the ball rolling. Well, looks like Greece is about to do just that:

GREEK FINMIN SAYS ENVISAGES TWO TYPES OF NEW BOND, ONE LINKED TO NOMINAL ECONOMIC GROWTH AND ONE A PERPETUAL BOND – FT

2. February 2015 at 12:12

@Charlie Jamieson: “two-tier wage system. … Schools will hire younger teachers rather than older teachers who command high wagers.” Employers always pay differently depending on qualifications. That’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about paying employees with identical qualifications, very different salaries. Just based on whether you’re a “new hire” or an “old hire”. That would reduce the problem of sticky wages … but it doesn’t happen.

@MF: “bid and ask wage rates not instantly falling for both recently unemployed and recently employed. Psychology is not limited to the unemployed.” It’s not really about psychology, and it’s not even about the “recently employed”. Even a long-term employed worker, who has been on the same job for decades, and is in no danger of being fired … because he doesn’t take a nominal wage cut, that dramatically impacts the ability of the employer to hire any new workers (possibly, at any wage at all, no matter how low).

As I say, I think you’re underestimating that most of the “sticky wage” effect comes from long-term employed workers, whereas most of your attention seems focused on workers at the margin, in transition between employment and unemployment. Yes, the transitional workers are the ones who don’t have jobs. But the explanation of why they don’t have jobs actually has little to do with their individual psychology or demands.

The primary cause of sticky wage-induced unemployment, is the sudden rising real wage cost of long-term employed workers, who themselves are in no danger of losing their jobs. They were perfectly happy with their old compensation, but they all suddenly received an unearned (real) pay raise, which of course they’re perfectly happy to keep.

All of your analysis focuses on the behavior of those without jobs, but they are not the primary cause of their lack of jobs, so there is essentially nothing they could do about changing their situation.

2. February 2015 at 12:25

There are maximum likelihood methods for getting the transition matrix so no ad hoc is necessary (e.g. lots of literature based on Hamilton (1989).

What is weird about incorporating a MA into the analysis is that you have to be really careful or else you will introduce some persnickety little autocorrelations that you would rather not have to deal with.

2. February 2015 at 12:38

Major.Freedom,

Yes, the wage stagnation probably did start earlier in 1973. Why:

1) The 1974 Oil Embargo

2) Japanese & German manufacturing was more competitive than US.

3) The economy was not able to handle the influx of baby boomer in the workforce. (Our current Demographics in reverse.)

4) The Vietnam War was ending. This country spent 10 years with the wrong priorities and lost our competitiveness and hurt a generation of soldiers.

2. February 2015 at 12:46

Everybody – we should totally listen to Ray Lopez, because he inherited his money and he’s been having opinions on things for two decades. That clearly makes him part of the cognitive elite.

We should also listen to Major_Moron. He’s right because he’s right. Says so on the label.

2. February 2015 at 15:45

David Friedman:

“I think I have now found a better venue for online argument and conversation. I mentioned in an earlier post a blog, Slate Star Codex, by an unusually able, energetic and fair minded poster. It turns out that not only does he write interesting essays, he also attracts a pretty high quality of commenters, making the comment threads interesting conversations, sometimes interesting arguments. Once it occurred to me to read the latest essay, for which the comment thread was still open, instead of whichever old essay looked most interesting, I had a brand new way of interacting with interesting people online……”

http://daviddfriedman.blogspot.com/2015/02/better-than-facebook.html

2. February 2015 at 16:22

Looking at those graphs it is clear so-called “supply side” tax cuts do nothing for increasing wages. Wages were down during Reagan, down during Bush and up during Clinton. Meanwhile we had a spectacular run of 40 years of increasing wages while the top tax rate was never below 70 percent.

3. February 2015 at 09:08

Thanks Amelanchier.

Jorge, I’ve proposed subsidizing the NGDP futures market, but it doesn’t really matter if they gain no “traction,” as that would merely indicate the Fed was on target.

Thanks Njnnja.

Travis, Yes that SlateStarCodex is a great blog.

Tom, What makes you think there is any causal link?

3. February 2015 at 16:04

Suppose the market for NGDP futures starts out with just the blogger and a handful of faithful blog commenters as active participants. To get the ball rolling, the blogger makes an opening bid of 3% and an offer at 6%. No one in the blog community has any special insight into what actual NGDP will be, so no one is particularly keen to carry large risk. Thus, trades are few and far between, usually at the 3% bid or 6% offer. Because liquidity is thin, positions cannot be easily built or offloaded, so other potential participants are discouraged from entering– even if they have superior knowledge into future NGDP. So yes, looking at such a futures market one would be able to gleen that the FED was on target… within a 3% interval. How would this be useful to anyone? A market that lacks liquidity, depth or active trading does not provide information, even if it correctly prices assets.

3. February 2015 at 17:11

*glean

4. February 2015 at 13:48

Jorge, I agree that this sort of market would not be very useful.

12. February 2015 at 23:13

You could run a Vector auto-regression and find impulse response functions if you are worried about lags. These are nice because you can find a cumulative effect of a lag rather than a mere level or ‘change’ correlation between periods. This seems like the obvious answer to me. Maybe I misunderstood you bleg.

I’m not sure that I would use polynomial functions for time. I’m not sure what theory would support that. Time fixed effects, on the other hand, are always a great idea.