Is Covid’s impact semi-permanent?

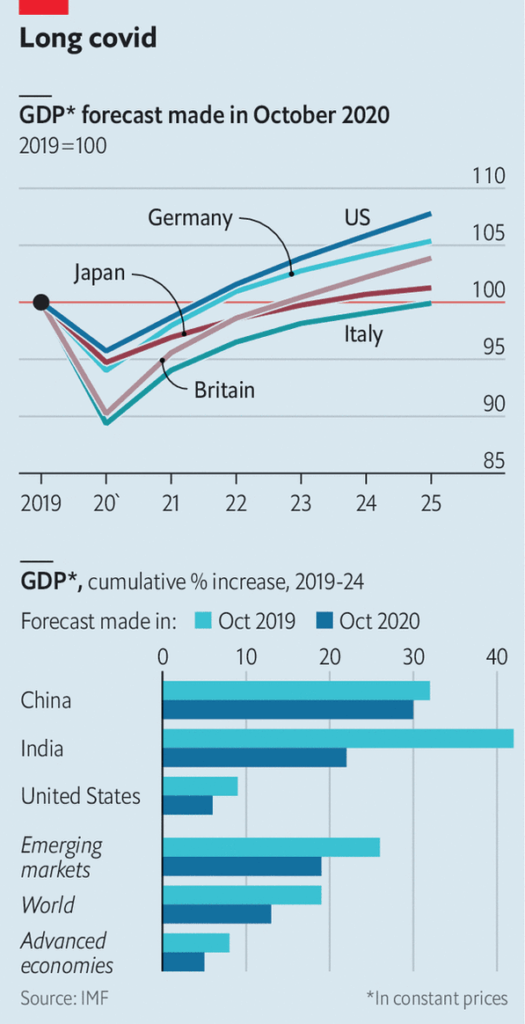

This graph in The Economist caught my eye:

Thoughts:

1. What’s up with India? And another lost decade for Italy?

2. Less immigration might slow growth in the US, but the slowdown is a global phenomenon. Immigration is a zero sum game for the world, and yet world growth is expected to slow.

[Update: I meant zero sum for the global labor force. Several commenters pointed out that it’s not zero sum for global GDP, because labor moves to where it’s more productive. I should have said, “and yet growth is slowing in each region.”]

3. It seems likely that Covid-19 will be over long before 2025, so there seem to be some semi-permanent effects. Why? It looks like a loss of roughly 3 percentage points in the US (or 0.6% per year for 5 years).

4. Perhaps the Fed won’t allow enough NGDP growth, and some of the lost growth will be employment related.

5. Or maybe productivity growth will slow. That could be due to less capital accumulation resulting from less investment during Covid, or slower technological progress.

6. The IMF forecasts may be wrong; maybe growth will not slow. Or maybe it will slow for reasons unrelated to the IMF model, such as Biden policies. (I doubt Biden would have a big impact, but who knows?)

7. But growth is expected to also slow outside the US, and the Great Recession also led to sharp reductions in long run RGDP forecasts for many countries, including the US. Why aren’t we expected to bounce back to trend?

I’d like to end up with a slightly different hypothesis, which I’ve been discussing on and off for almost a decade. Maybe trend growth is slower than we assume. Growth during 2009-2019 was in the 2% to 2.5% range, but that was entirely during the expansion phase of the business cycle. During that period, unemployment fell from 10% to 3.5%. That’s unsustainable.

The correct way to measure trend growth is to compare two widely separated years with similar unemployment rates. That approach often yields trend growth estimates that are lower than the consensus. If the IMF is correct, then total growth between 2019 and 2025 will be roughly 7.8%, or 1.3% per year. Maybe that’s the new normal. After all, population growth is gradually slowing, and productivity growth is also slow, although poorly measured.

I’ve recently been saying the new normal is 1.5% measured trend growth, and I’m sticking with that. FWIW, if the IMF is correct about the 7.8% growth from 2019-25, then RGDP growth from 2007:Q4 to 2025:Q4 will average 1.54%. If unemployment is around 4.5% in 2025 (as in 2007), then that will likely be the new long run trend. That’s relatively bad, and may help to explain why we see such low real interest rates.

PS. I say “relatively” bad; it still means the richest big country the world has ever seen will keep getting richer and richer and richer. It beats living in a disease-ridden London slum in 1831. Or a rural French village in 1324. Those people did not have pet psychologists to address depression in dogs and cats. We are bursting with happiness; I see it on twitter every single day. 🙂

Tags:

25. October 2020 at 18:13

Immigration is NOT a zero-sum game for the world. Not even close.

Trillion dollar bills on the sidewalk.

25. October 2020 at 19:05

Scott,

I don’t understand the comment either. Wasn’t the previous narrative always that immigrants, not all but many, can realize a greater potential in the host countries than they could in their home countries?

25. October 2020 at 19:19

David and Christian, Yes, you are of course correct. I meant it was zero sum in terms of labor force changes. So labor force changes cannot explain the fact that growth is slowing in all areas, but it can explain why global GDP in aggregate might slow, as you say.

I added an update.

25. October 2020 at 19:56

There is no such thing as the “new normal”. There is only good policy and bad policy.

Growth rates have only been low because investment is low. And investment is low because regulations were extraordinarily high. Take for example fisherman off the coast of Maine who were told that 50,000 square kilometers were “off limit” to fishing. That’s how absurd the government regulations are, and they exist in every industry. Once you get that regulation under control, which DJT has tried to do, and you actually give entrepreneurs freedom, you will see stronger investment and stronger growth.

“New Normal” is nothing but propaganda.

25. October 2020 at 20:05

I see that David and Christian beat me to commenting on zero sum game. I would expect that increased marginal output of the immigrant is a benefit globally in aggregate even though it is a loss to the country they left.

25. October 2020 at 20:22

Decline of cities should have a real GDP effect. The economics of major cities already seemed to be having serious issues with the high taxes. COVID sped up the process of people making decisions to move.

However, the good things of cities and and agglomeration economics of knowledge will be a drag on gdp and a real loss.

25. October 2020 at 21:40

Ken, Yes, but the population effect is probably too small to explain the changes the IMF foresees, even if we lost a million immigrants. The US has 330 million people.

Sean, I’d expect any Covid effects to wear off by 2025. Don’t forget that soon after 9/11 NYC was booming again, and I recall people saying that 9/11 would make people reluctant to live in tall buildings.

26. October 2020 at 04:17

LOL. Banks are “Black Holes”. Economists don’t know a debit from a credit. All $15 trillion in bank-held savings are inert. There is only one way to activate monetary savings, for their owners, saver-holders, to spend/invest entirely outside of the payment’s system (a velocity relationship).

And the stabilization of interest rates “moderate long-term interest rates” has lead to the de-stabilization of money stock growth. All you have to do is look at the last 20 years. The money stock and thus economic output have varied wildly.

It’s exactly as Lawrence K. Roos, Past President, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and past member of the FOMC (the policy arm of the Fed) as cited in the WSJ April 10, 1986:

“…I do not believe that the control of money growth ever became the primary priority of the Fed. I think that there was always and still is, a preoccupation with stabilization of interest rates”.

In “A Monetary History of the United States 1867–1960” (1963), Nobel Laureate Dr. Milton Friedman, in collaboration with Dr. Anna J. Schwartz, presented an exhaustive historical analysis of the U.S. money supply growth.

Friedman concluded that the Federal Reserve should pursue economic stability, by controlling the rate of growth of the money supply (the k-percent rule).

The FED was to achieve this stability by following a simple rule that stipulated that the money supply be increased at a constant annual rate tied to the potential growth of N-gDp.

Monetarism posits that a steady, moderate, and accurately measured growth of monetary flows, volume times transactions’ velocity, could guarantee a constant rate of economic growth with low inflation.

The variability of the money stock growth rate was to be expressed as a percentage (e.g., an increase from 3 to 5 percent).

But today the short-term, medium term, and long term variability of the money stock (now divorced from interest rate manipulation), and thus the economy, is at all-time highs.

26. October 2020 at 04:21

The Covid-19 rebound is not like Milton Friedman’s “Plucking Model”.

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4154412-unemployment-and-friedmans-plucking-model

“Contrary to the data on output, which consistently returns to a maximum output trend, unemployment does not regularly return to a minimum”

Link also: “The Unit Root of the Missing Monetary Monomial”

https://alhambrapartners.com/2020/10/21/the-unit-root-of-the-missing-monetary-monomial/

26. October 2020 at 06:03

I doubt this is the answer, but could the key be the word “cumulative”? That if GDP in 2020 is $X below the earlier estimate and that gap closes over the next 3-4 years so that the predicted GDP for 2024 is exactly the same predicted in 2019, we have a large cumulative gap (a triangle) that also means 2025 and forwards are completely unchanged.

26. October 2020 at 06:46

Perhaps the answer was your sidebar re: Growth “although poorly measured”. Your framing of the problem is appealing–but it feels wrong. You attempt to hold other things equal with your “measured” growth. Implicit, I think, in your framing is that “poorly measured” is that which is mismeasured on a constant basis—hence your hypothesis could hold (I realize you are thinking out loud). But for many who believe in “poorly measured” believe that is where the increasing growth is coming from—more like an increase in growth, not a constant layered on top of measured.

I don’t know how important past bad forecasts are. But Lawrence Lindsay points out the Fed over stated projections for Obama and understated it for Trump. Making no statement re Trump versus Obama–just on forecasts.

Have you “back tested” your idea?

population matters in total of course which is what you are discussing—but per person is what really matters.

26. October 2020 at 08:15

Bill, Maybe, but I’ve never seen data reported that way, so I sort of doubt it.

Michael, You said:

“but per person is what really matters.”

Total matters too. I more impressed by the US than by (richer) Liechtenstein.

26. October 2020 at 08:49

As Larry Summers surmised: “With a somewhat different list of factors in mind, the Harvard economist Alvin Hansen labeled the failure of private investment to fully absorb private savings “secular stagnation” because of the threat that it would mean insufficient demand.”

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/03/larry-summers-on-secular-stagnation.htm

As Luca Pacioli, a Renaissance man, “The Father of Accounting and Bookkeeping” famously quipped: “debits on the left and credits on the right, don’t go to sleep with an imbalance”.

An expansion of time deposits, saved deposits, is prima facie evidence of a leakage which collects in the form of unspent balances. With interest-bearing deposits now exceeding $15,000,000,000,000 it is undeniable that this is an important factor retarding the growth of the economy. The growth of time deposits shrinks aggregate demand and therefore produces adverse effects on GDP. An increase in bank CDs adds nothing to GDP.

26. October 2020 at 09:36

As Murry N. Rothbard pointed out in “Austrian Definitions of the Supply of Money” money stock definitions: “fails from focusing on the legalities rather than on the economic realities of the situation”

https://mises.org/library/austrian-definitions-supply-money

Take John A. Tatom’s “The Effects of Financial Innovations on Checkable Deposits, Ml and M2”

https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/90/07/Financial_Jul_Aug1990.pdf

“The widely accepted view is that these financial innovations have rendered Ml less useful, or even useless, as a monetary policy target.2 The related view—that the broader aggregate M2 has been unaffected by these innovations and therefore remains a useful target—is almost as widely shared.”

Link: G.6 DEBITS AND DEPOSIT TURNOVER AT COMMERCIAL BANKS

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/releases/g6comm/g6_19961023.pdf

See: Annual Rate of Deposit Turnover

For (1) demand deposits -other banks

(2) other checkable deposits

(3) savings deposits

Notice that since the introduction of ATS, NOW, and MMDA accounts, deposit turnover from financial innovations wasn’t becoming all that popular.

That is principally all demand drafts clear through total checkable deposits. Ergo, non-M1 components rarely turn over. That speaks volumes. Rates-of-change in “Total Checkable Deposits (TCD)” therefore represents

As “New Measures Used to Gauge Money supply” WSJ 6/28/83

“The experimental measures are designed to resolve some of the confusion by isolating money intended for spending, the money held as savings. The distinction is important because only money that is spent-so-called “true money” – influences prices and inflation.”

26. October 2020 at 09:37

Is there any reason the US couldn’t get back to labor force participation rates, unemployment rates, and inflation rates similar to those of the late 1990’s? I guess I don’t see what is unsustainable about that kind of a labor market, except for central bank incompetence.

26. October 2020 at 09:42

Merit based immigration also has benefits for the source country as it encourages self investment in human capital.

26. October 2020 at 10:01

But there ought to be some permanent effect: investments not made, sill depreciation, inventions not invented, expectation of slower real growth in the future (indeed a reminder that supply shocks as well as demand shocks are possible) as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

26. October 2020 at 14:57

Scott,

Thanks for the update, much appreciated.

26. October 2020 at 15:51

To some extent a globalized economy is a cheap labor economy. Why invest in productivity if labor is cheap?

Aggregate demand has been weak for decades, due to Central Bank phobia regarding inflation. Remember, until very recently, the US Federal Reserve actually targeted a 5% unemployment floor.

Actually, the world is glutted with factory capacity in nearly everything, from smartphones to cars to steel to clothing to even food. The only shortages are in housing and that is due to property zoning.

This suggests that output could rise for quite a while, thus improving productivity as measured by output per hour.

My guess is that fiscal-monetary policies should be more stimulative. Covid-19 throws a monkey wrench into everything of course.

26. October 2020 at 16:12

On immigration:

Michael Warby has been working on some papers on immigration disrupting social stability, and if one looks at a Syria or an Iraq, one can how economic progress fares when there is a lack of social stability.

Of course, the most ardent immigrationists in US history were the (horrid, insane) slavers, famously bringing cheap labor to the US in 1619 and thereafter.

This immigration has resulted in degrees of social instability ever since, particularly from the viewpoint of the slaves and their descendants.

Was the immigration of slaves to the US a long-term positive for the US economy? Did productivity rise or fall in the US, after cheap-labor slaves were imported, as measured by output per worker? I suspect labor output per hour fell relatively, but income was distributed upwards.

If a large number of cheap laborers were brought into the US in the future, as suggested by Byran Caplan, would we not expect labor productivity to fall?

And if output per hour by laborers falls, do we not then expect wages per hour to fall also?

And if wages fall, then what happens to social stability?

26. October 2020 at 17:21

OT, but interesting conundrum:

Communist China has a shrinking labor force and little in-migration.

Yet Scott Sumner has posited that China will not be caught in “the middle-income trap” in years ahead.

Some interesting talk about China’s economic growth:

https://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2020/10/will-china-be-caught-in-middle-income.html

It will be interesting to watch China’s economic progress in years ahead. They seem to have a great deal of social stability, as does Japan and S Korea.

But somehow, slower economic growth seems to set in, all over the world.

27. October 2020 at 06:03

India has been going through a slowdown well before covid hit. A big part of the slowdown is crony capitalist sitting on huge amounts of bad debt built over last two decades. This is going to take time to unwound.

I recommend “Bad Billionaires” on Netflix – really goes to core of the malaise.

27. October 2020 at 06:56

Re: I did say “population matters in total of course” and I really was thinking of how you look at Japan on “per capita” concept not Lichtenstein, or Vatican City 🙂

27. October 2020 at 10:24

Thomas, Investments not made don’t have a permanent effect.

Ben, You said:

“Michael Warby has been working on some papers on immigration disrupting social stability, and if one looks at a Syria or an Iraq, one can how economic progress fares when there is a lack of social stability.”

Canada, Australia and Switzerland are some of the highest immigration countries in the world.

Dhruv, Wasn’t Modi supposed to be the guy who was “good for the economy”?

27. October 2020 at 10:38

re: “Aggregate demand has been weak for decades, due to Central Bank phobia regarding inflation”

How so? The Phillips Curve has already been denigrated. And if there is an inflation-unemployment trade-off curve, it is shifting to the right, and at an accelerated rate.

In fact, to assume that the Federal Reserve can solve our unemployment problem is to assume the problem is so simple that its solution requires only that the manager of the Open Market Account buy a sufficient quantity of U.S. obligations for the accounts of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. This is utter naiveté.

Clearly, the notion that unemployment can be permanently reduced to a tolerable level (which throughout time has varied), simply by pumping up aggregate demand is both naïve and dangerous.

27. October 2020 at 11:22

Re: “But somehow, slower economic growth seems to set in, all over the world”

The nefarious delusion that snares the unwary and shallow intellect is that banks are intermediaries, matching savings with investments.

Never are the banks in our payment’s system intermediaries in the savings investment process. This is universally misunderstood.

See e-mail from Thornton:

Re: Savings are not a source of “financing” for the commercial bankers

Dan Thornton

Thu 3/9, 2:47 PMYou

See the graph below.

http://bit.ly/2n03HJ8

Daniel L. Thornton

D.L. Thornton Economics LLC

xxxxx

And large CDs aren’t even included in M2 (as in FOMC’s proviso “bank credit proxy” which used to be included in the FOMC’s directive during the period Sept 66 – Sept 69).

——

Or take George Selgin (advisor to Congress): July 20, 2017

“This is nonsense, Spencer. It amounts to saying that there is no such things as ‘financial intermediation,’ for what you claim never happens is precisely what that expression refers to.”

Economists simply haven’t been able to fashion the payment’s system in a system’s context – to think it all the way through.

As Luca Pacioli, a Renaissance man, “The Father of Accounting and Bookkeeping” famously quipped: “debits on the left and credits on the right, don’t go to sleep with an imbalance”.

See Dr. Steve Keen, an Australian economist: “Banks don’t “intermediate loans”, they “originate loans”.

http://bit.ly/2GXddnC

It involves understanding that banks create new money whenever they make loans to, or buy securities from, the nonbank public. It is almost impossible for the commercial banks to engage in any type of activity without causing an alteration in the supply of money, irrespective of the supply of loanable funds.

The Bank of England:

http://bit.ly/2sphBHD

Working Paper No. 529 “Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds — and why this matters” –Zoltan Jakab and Michael Kumhof May 2015

BOE:

“Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits. The amount of money created in the economy ultimately depends on the monetary policy of the central bank”

In this train of thought it logically follows that an increase in bank CDs (pirated from other banks in the system) adds nothing to gDp.

27. October 2020 at 11:35

@ B Cole,

If we “brought” millions of low skilled immigrants who did not want to come to the US, I’d agree that the results would be bad. If we allowed millions of skilled immigrants to come (graduate scholarships in STEM subjects could help), that would be a different story.

27. October 2020 at 13:19

What I was trying to say is the original forecast could have been say GDP of:

2019 to 2024: 100, 103, 106, 109, 112,

And now updated to:

100, 92, 99, 106, 112

So now permanent damage.

28. October 2020 at 01:01

‘There is no such thing as the “new normal”. There is only good policy and bad policy.’

‘Bad policy’?

” . . . give entrepreneurs freedom, you will see stronger investment and stronger growth.”

“‘Direct existential threat’ of climate change nears point of no return, warns UN chief

If we do not change course by 2020, we risk missing the point where we can avoid runaway climate change, with disastrous consequences for people and all the natural systems that sustain us.”

https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2018-09-10/secretary-generals-remarks-climate