Everything you want to know about NGDPLT

In the past, when people have asked me about NGDP targeting I’ve often pointed to my own Mercatus paper. In the future, I’ll probably point to an excellent paper by David Beckworth, which just came out today.

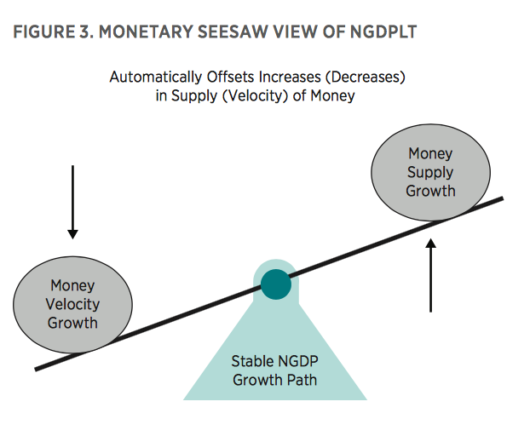

David is especially good at explaining the intuition behind NGDP targeting. Here’s one diagram:

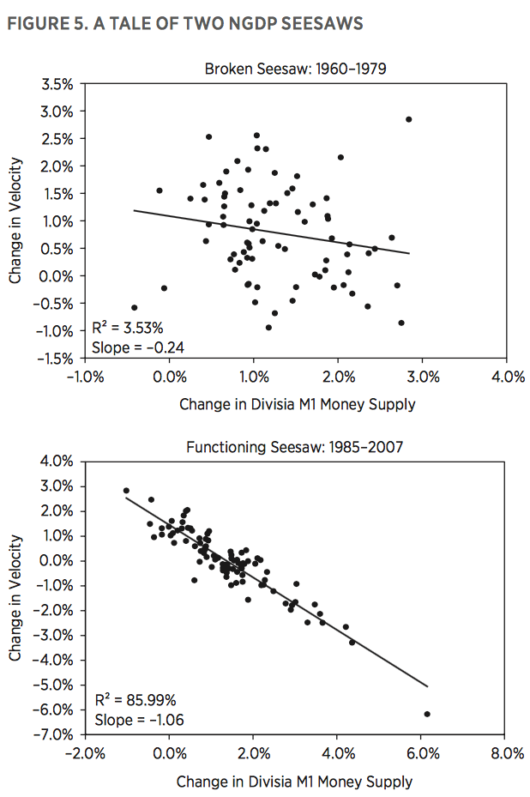

And this figure shows how it works out with actual data:

And this figure shows how it works out with actual data:

Notice how during the Great Moderation, the Fed tended to adjust the money supply to offset changes in velocity, whereas during the less stable 1960s and 1970s they did not do so.

Notice how during the Great Moderation, the Fed tended to adjust the money supply to offset changes in velocity, whereas during the less stable 1960s and 1970s they did not do so.

David looks at NGDP targeting from many different angles, and in the second half of the paper he considers a number of objections that have been raised. One issue is whether the Fed would be able to bring NGDP back to the trend line after an overshoot. Would that be too controversial? David offers three counterarguments:

First, as mentioned earlier, if the public understands NGDPLT and finds it credible, then it will have less incentive to engage in excessive spending that pushes NGDP above target in the first place since the Fed will be expected to offset it. The public’s expectation of stable total dollar spending growth, then, will become self-fulfilling. This lowers the likelihood of the Fed having to correct an overshoot of the target. Second, even if there were an overshoot, the Fed need not engineer an outright contraction of NGDP. As seen in panel B of figure 2, the Fed could simply slow down the rate of NGDP growth until its level returned to the targeted growth path. Finally, the existing monetary policy framework faces its own version of this fear. Yet policymakers have found ways to tighten monetary policy when needed. It should be no different under NGDPLT.

I’d add a fourth factor. The public thinks in terms of levels, not growth rates. That’s why they view years like 2010 as “recession years”, whereas economists see them as recovery years, as “expansion”. If there is an overshoot of NGDP that means the economy is overheating. Going back to “normal” does not feel at all (to the public) like going from a normal to a below normal economy. There is generally very little increase in unemployment when the economy reverts down to the trend line from overheating, unless it’s been overshooting for a long time, in which case you do want to return to normal at a very gradual pace. (And you also want to replace the Fed chair.)

PS. I also recommend a new book based on a Mercatus/IHS conference from early 2018, which has a number of excellent papers on monetary policy. The conference honored Allan Meltzer’s contributions to monetary economics. Meltzer was one of the most influential monetarists of the 20th century.

Tags:

2. October 2019 at 11:25

“The public thinks in terms of levels, not growth rates.”

True, but for presidential elections, growth rates matter more than levels.

2. October 2019 at 12:54

I’ve had good results with Divisia M4 less Treasuries.

The Divisia experts generally recommend using as wide a Divisia index as possible (so it’s a little curious that you report Divisia M1, but I guess it has a better R^2), but I think including Treasuries causes some unnecessary distortions during the financial crisis.

2. October 2019 at 14:15

Excellent charts above, thanks for citing them. Simplifies things nicely.

2. October 2019 at 16:15

during the Great Moderation, the Fed tended to adjust the money supply to offset changes in velocity, whereas during the less stable 1960s and 1970s they did not do so.–Scott Sumner.

So, if we are in a period of negative interest rates, would lowering interest rates more, that is going deeper into negative territory, actually encourage people to move into cash, thus reducing velocity?

In Japan, people hoard paper cash to the equivalent of $8,000 per resident.

2. October 2019 at 18:16

“One fear about NGDPLT is that once it is up and running, potential real GDP may change and cause the trend inflation rate to be different than what Fed officials expected it to be when they established the NGDP target.”

One way to address this concern is to do a moving average of real GDP over a long time period (maybe a decade or so) and every quarter add the long run trend inflation figure you want to see. This would be the nominal GDP for the given quarter that the fed targets.

A modification of this approach would be to look at a moving average of per worker labor output over a decade or so and multiply this by current size of the total labor force for real GDP average growth, then add the trend inflation you want to see for the nominal GDP that the Fed should target.

2. October 2019 at 23:08

Richard, something like that would probably work.

And there’s also not too much of a problem changing the nGDP level target trajectory, I believe, as long as you only change the target that’s at least a few years in the future. (Very similar actually, as if the current Fed announced I’m 2019 than in 2023 onwards their inflation target will be 3% instead of 2%.)

Just don’t change the current target, or the very near future target.

But they can also just ignore these concerns altogether, and set eg a fixed 3% growth trajectory per capita. If real growth comes to a halt, that’s a bearable 3% inflation. If real growth accelerates, in the most extreme case we’d be getting some deflation. Contrary to popular opinion deflation is not a problem by itself, just the opposite. Deflation has a problematic image because it’s often observed when nGDP shrinks.

(Of course, zero growth isn’t the extreme case for the downside direction. A shrinking real economy is. If the real economy shrinks over a long time, we have real problems.. Not sure whether monetary policy will be able to help much.)

Measuring nominal GDP is pretty straightforward. Measuring inflation (and thus real GDP) is pretty subjective and ambiguous.

George Selgin’s book Less Than Zero drills into the idea of stabilising nominal GDP per capita at a constant rate instead of the steady growth Scott favours. It’s freely available online, and Scott wrote a new intro for it a year or two or so ago.

3. October 2019 at 03:49

So how to hit NGDPLT?

In next recession, helicopter drops.

That ain’t me talking, in my tin-foil hat. That is the world’s largest investor, BlackRock!

https://www.blackrockblog.com/2019/10/03/going-direct-how-central-banks-could-deal-with-the-next-downturn/

You know, I was making my diary vigil to the Hall of Tin-Foil Hats inside the Temple of Orthodox Macroeconomic Theology, and it was…crowded! That I was, elbowed aside as I paid homage to the Tin-Foil Hat Totem.

What fun is this?

3. October 2019 at 06:04

Good post. Beckworth is doing some good very stuff.

3. October 2019 at 07:00

Beckworth: “First, as mentioned earlier, if the public understands NGDPLT and finds it credible, then it will have less incentive to engage in excessive spending that pushes NGDP above target in the first place since the Fed will be expected to offset it. The public’s expectation of stable total dollar spending growth, then, will become self-fulfilling. This lowers the likelihood of the Fed having to correct an overshoot of the target.” Our most severe economic problems have been the result of financial crises brouht on by asset bubbles. Overshoot seems the least of our problems. My question: how does NGDPLT address the problem of asset bubbles? The consensus is that contractionary monetary policy isn’t used to burst bubbles. The dilemma faced by the Fed is evident today, as the Fed is caught between the risk of an asset bubble and the risk of a recession. What’s a monetarist to do?

3. October 2019 at 07:14

I’m glad Beckworth has started gaming out how the public will see NGDPLT.

It’s much simpler:

Everything will be the fault/blame of politicians.

High inflation/ low RGDP will be bad for politicians

Low inflation / high RGDP will be good for politicians.

This will over time turn into RULES the public believes by looking at trends.

Example: Increases in public sector pay that do not deliver productivity gains = INFLATION = less low rates for private sector RGDP

Expect, policies will come with CBO NGDP scoring, so an Immigration policy of taking 100K doctors per year from the Earth’s 8M but requiring them to work in Medicaid networks will be a score: this will be Real Growth, not Inflation (prices will fall, bc supply)

—-

I often talk about the glorious day in Jan 1993, when Greenspan sat down Bill Clinton and told hm,

“So Bill you ran on ‘investing’ in blah, blah, blah , if you do this, I’m going to have to raise rates faster which will price out more of the private sector borrowing growth”

And that FORCED BILL CLINTON to look in the mirror and REALLY decide if he BELIEVED his investing would be better than private sector and he DROPPED 80% OF HIS CAMPAIGN PROMISES in less than an hour.

This is what NGDPLT really does, it forces EVERYONE to really think about whether their ideas are pro-growth or pro-inflation.

It makes GREENSPAN THE FED CHAIR FOREVER.

Yahtzee!

3. October 2019 at 12:24

It’s a brilliant example of persuasive communication. Kudos to Beckworth for writing it in such an approachable style. Rather than a sort of cold, academic format, he structured it more like a “Note” you’d see released by an Investment Bank’s chief economist.

If this policy ever gets adopted, I think you’ll see equities rally. Imagine the end of the business cycle…much lower probability assigned to future recessions, makes stocks more valuable.

3. October 2019 at 13:57

From Beckworth’s Paper: “…Sumner more recently has promoted targeting the NGDP forecast using an NGDP futures market that the Fed would set up and run. A more modest forecasting approach is adopted here, where existing NGDP forecasts are used in a modified Taylor Rule….”

From an engineer who is not an economist, Sumner’s approach appears to be more of an automatic closed loop control system while Beckworth uses rules based on human forecasting. Intuitively I think the Sumner approach is much more likely to work and is less susceptible to the blowing winds of political actors.

5. October 2019 at 09:35

Rayward, The problem hasn’t been “bubbles”, it’s been unstable monetary policy.