Language and unemployment

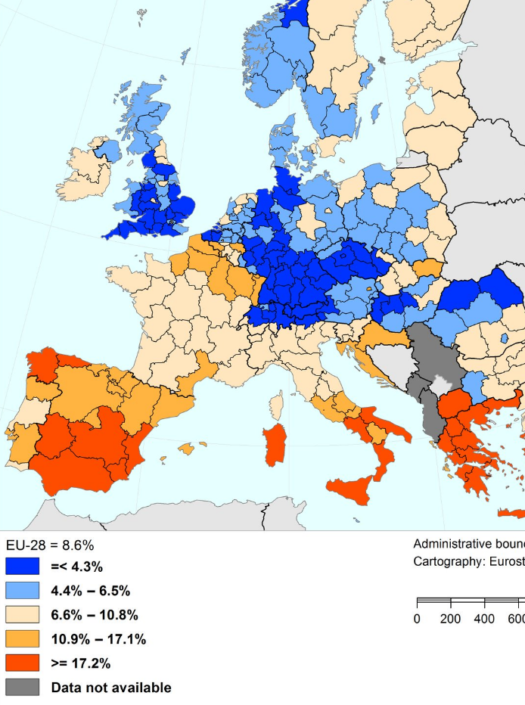

I like maps. Randy Olsen recently linked to an interesting map of European unemployment:

Before seeing this map I knew that Germany had higher lower unemployment than France. And indeed you see a dramatic change in the unemployment rate right where the two countries meet—at the Rhine.

My assumption has been that the lower German unemployment reflects better labor market regulations. But this graph hints at another difference—language. Let’s suppose that Germanic language areas have lower unemployment than Romance language areas. How would we test whether language or government policies are more important?

One approach would be to note that some countries have multiple languages. Thus southern Belgium and southwestern Switzerland speak Romance languages, and the rest of those countries mostly speak Germanic languages.

Now look at the map. I see a sharp unemployment divide in Belgium, right on the line between French and Flemish. And in Switzerland, I see much higher unemployment in French-speaking Geneva, Vaud, and Valais, as well as Italian-speaking Ticino. Below is a map of Switzerland, so you can see the cantons more clearly.

I also notice an area of very high unemployment from Greece to southern Italy to Sardinia to southern Spain. So maybe it’s not language, maybe it’s latitude. Or maybe both language and latitude are proxies for culture.

Before we fall in love with this theory, however, there is just one problem. As recently as 2005, Germany had about 11% unemployment and was regarded as the “sick man of Europe”. We should be suspicious of cultural explanations that apply in one decade, but not the next. Surely culture doesn’t change very much in 12 years!

In the end, I’m included to think, “it’s complicated”. There are probably lots of factors that are playing a role here. Southern Belgium was once richer than northern Belgium, but today it’s more of a rust belt, as its old heavy industry is less competitive than the newer firms in the Flemish areas to the north. Perhaps there are similar explanations for Switzerland. Perhaps culture and government policy interact—thus people in the far south of Europe have a culture that leads to political outcomes associated with excessive labor market rigidity.

So no easy answers, but the map is certainly food for thought.

PS. Unemployment is related to wealth, and indeed probably more closely related than in earlier decades. But the correlation is still far from perfect. Northern Italy does better on wealth than employment (check out my “rich heart of Europe” post.) For instance, Lombardy has more unemployment than northern England, despite being richer. Or compare (rich) Paris with the Czech Republic.