James Bullard has a new paper out discussing the NeoFisherian perspective on interest rates. According to the NeoFisherian view, holding interest rates at a low level for a long period of time will lead to persistently low inflation rates. That’s because (according to the Fisher effect) nominal interest rates tend to be correlated with inflation rates, at least in the long run.

James Bullard says he used to hold the opposite view:

Indeed, during the past six years I have warned, along with many others, that the Committee’s ZIRP has put the U.S. economy at considerable risk of future inflation. In fact, my monetarist background urges me to continue to make this warning right now!

Actually, Milton Friedman would have been dismissive of that view:

Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy.

Instead, the view that Bullard attributes to monetarists is actually the Keynesian/Austrian view. It’s Keynesians and Austrians who reason from a price change. They are the ones who insist that low interest rates are expansionary.

The NeoFisherians had a perfect opportunity to fix this flaw in macroeconomics, but instead fell into the trap of making exactly the opposite mistake. NeoFisherism is also an exercise in reasoning from a price change, but in their case they assume that low rates are disinflationary, not inflationary. That is, they assume that low rates are tight money, whereas Keynesians and Austrians tend to assume it’s easy money. It’s neither.

If the NeoFisherians are going to make any headway convincing outsiders, then need to do two things that Bullard failed to do in his paper:

1. Discuss the Keynesian/Austrian/Monetarist view of the liquidity effect. Why have central bankers assumed for decades, even for hundreds of years, that lower rates are expansionary? Are they really that delusional? There are literally 100s of natural experiments where central banks adjusted interest rates unexpectedly. In each case we can observe the market reactions. How do exchange rates react? How do commodity prices react? How do TIPS spreads react? The Bullard paper, and other papers I’ve seen on NeoFisherism, simply glosses over these key questions. But these are exactly the questions that skeptics would want answered.

2. NeoFisherians need to provide a plausible example of a shift toward lower rates leading to a lower inflation environment. The example provided by Bullard is not at all persuasive, for reasons outlined by Ryan Avent:

Where I think Mr Bullard begins to go off course is in treating the Fed’s behaviour like a zero-interest-rate peg. Yes, interest rates have been below 0.5% for nearly eight years, and the Fed has consistently promised to raise rates gradually. But it has promised to raise rates gradually, which is not the sort of thing a zero-rate targeting central bank would do. More importantly, markets have believed that the Fed would raise rates. When the fed fund futures contract for July 2016 began trading back in 2013, markets reckoned that the interest rate set at the July meeting would be in the neighbourhood of 1.5% to 2%. That was in line with the dots published by the Fed at the time. The Fed told markets that rates were going up, and markets saw no reason to disbelieve.

As it turned out, both markets and the Fed were far too optimistic; over time the expected path of rate hikes has been both pushed forward into the future and it has flattened. Markets now think that the fed fund rate will be no higher than 1% three years hence. Maybe this shift has occurred because the Fed has signalled more strongly that it is pursuing a zero-rate peg, but I doubt it; in every published projection since 2013, the dots have continued to rise up to some “normal” rate well above zero.

I would argue that Mr Bullard is wrong; it is not the case that the Fed is choosing low rates and inflation expectations are therefore converging toward a low level. I would argue that the Fed has been targeting very low inflation, and falling inflation expectations imply much lower interest rates in future.

This dynamic is there back in 2013. In its projections the Fed indicates that rates will rise steadily, even as it projects that inflation will be extraordinarily low, just over 1% in 2013, converging, finally, toward 2% by the end of 2015. Essentially every set of Fed projections since then has shown the same thing. It allowed its QE programmes to end despite too-low inflation, and it raise its interest rate in December despite too-low inflation. The Fed has signalled very strongly that markets should expect inflation to remain at very low levels, indeed, below target. It would be shocking if inflation expectations hadn’t trended inevitably downward.

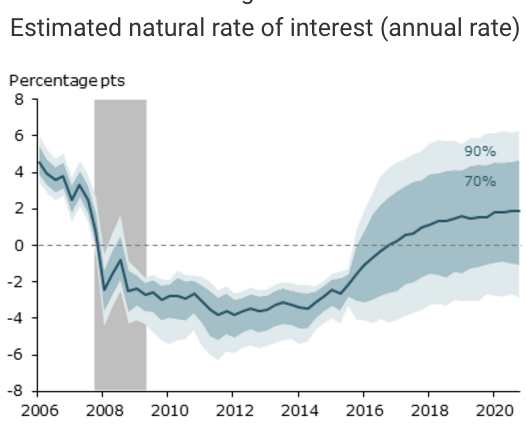

Now return to the Fisher equation. If the global real interest rate is in the neighbourhood of 0% and expected inflation is in the neighbourhood of 1%, that suggests the Fed will have an extremely difficult time raising nominal interest rates beyond 1%. Mr Bullard has the regime right, but the causation wrong. The Fed has driven the economy into this rut in its determination to keep inflation low.

I agree with Ryan Avent, except that last part about the difficulty the Fed would have in raising inflation.

In fact, there is a good example of NeoFisherian in action, which occurred just last year. As we will see, it is consistent with my previously expressed interpretation of NeoFisherism, and not consistent with the views of either NeoFisherians, or anti-NeoFisherians. The truth is orthogonal to the debate. Both sides are missing the point. Whether low rates are expansionary or contractionary depends entirely on whether they are achieved via an expansionary or a contractionary monetary policy.

It recently occurred to me that Switzerland circa January 2015 is an almost perfect example of NeoFisherianism is action. In previous posts I argued that the perfect NeoFisherian policy had two parts:

1. A promise to gradually appreciate the currency against a major currency, which would reduce interest rates via the Interest Parity Theorem.

2. A simultaneous once and for all large appreciation in the currency, which would exert a contractionary impact on prices that was large enough to prevent an immediate rise in the price level from the lower interest rates caused by step #1.

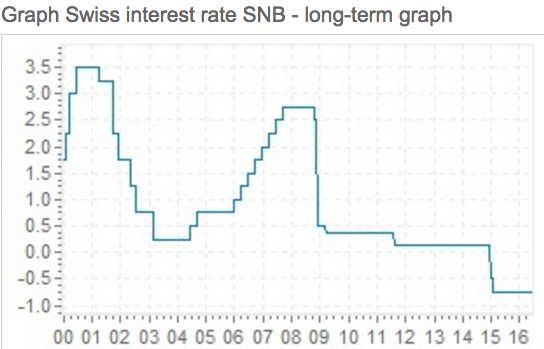

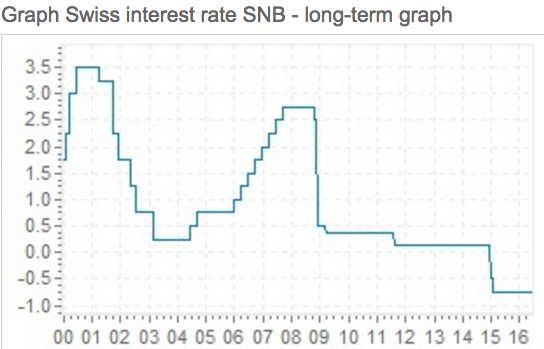

So step #1 reduces long run inflation via the PPP effect, and step #2 prevents Dornbusch-style overshooting in the short run. The Swiss didn’t announce precisely this policy, but the policy they did announce was virtually identical in all meaningful respects—and it had exactly the effect predicted by the NeoFisherians (but not for the reasons they assume). Here’s what Switzerland did to interest rates in January 2015:

Notice that interest rates fell from 1/8% to negative 3/4%, almost immediately. Because of interest parity, that created an expectation that the Swiss franc would gradually appreciate over time, which leads investors to expect lower trend inflation in Switzerland, compared to neighboring countries.

Notice that interest rates fell from 1/8% to negative 3/4%, almost immediately. Because of interest parity, that created an expectation that the Swiss franc would gradually appreciate over time, which leads investors to expect lower trend inflation in Switzerland, compared to neighboring countries.

But how did the Swiss authorities make sure this decrease in interest rates had a contractionary impact? The answer is simple; they did a simultaneous, once and for all, massive appreciation in the SF. Not a formal appreciation through government fiat, but rather by switching from artificial peg of 1.2 SF to the euro, to a floating exchange rate. The market (correctly) took this as a signal of tighter money, and the SF promptly rose by about 10% to 15% against the euro. But they could have achieved the same effect by simply revaluing the SF upward by the same amount, by fiat.

The upshot of all this activity was a sharp decline in Swiss inflation:

A skeptic might argue that inflation fell for some other reason, say falling oil prices. That might be part of it, but on the very day the new policy was announced, I recall people predicting slower RGDP growth and lower inflation, and they were correct. I’m confident that if a Swiss CPI futures market had existed, then CPI futures would have declined on this policy change.

A skeptic might argue that inflation fell for some other reason, say falling oil prices. That might be part of it, but on the very day the new policy was announced, I recall people predicting slower RGDP growth and lower inflation, and they were correct. I’m confident that if a Swiss CPI futures market had existed, then CPI futures would have declined on this policy change.

So the Swiss got exactly the result predicted by the NeoFisherians. A Keynesian skeptic will say; “Yes, both interest rates and inflation fell, but the lower interest rates did not actually cause the lower inflation. Indeed ceteris paribus the lower interest rates raised inflation, but the sharp appreciation of the SF put even more downward pressure on inflation.”

The problem with this argument is that whenever market interest rates decline, things are never ceteris paribus. Let’s take the standard Keynesian interpretation of an open market purchase. Say the Fed unexpectedly increases the monetary base by 2%, and this causes nominal interest rates to decline. Is the policy inflationary? Probably yes, but not for the reason that Keynesians assume. Other things equal, the lower interest rates will tend to lower velocity, and hence will tend to lower inflation. More than 100% of the heavy lifting for higher NGDP comes from the 2% increase in the base, and less than 0% comes from the lower interest rates.

The preceding point isn’t even controversial; it’s part of the standard monetary economics 101 literature. But macro has moved so far in an interest rate oriented direction that many people have forgotten these basic truths, or else they never even learned them. Blame Woodford if you wish. I blame almost the entire profession. In any case, yes, it’s actually the appreciation of the SF, not the lower interest rates, which causes lower inflation. But it’s also true that it’s the increase in the money supply, not the lower interest rates, that cause higher inflation in the standard Keynesian policy case.

Some will complain that my example only works in the special case of exchange rate manipulation, and that NeoFisherism does not work in a closed economy. Not so. Instead of a sudden appreciation of the SF, the Swiss could have achieved the same contractionary result by combining lower interest rates with:

1. Lower official gold prices (A reverse of FDR’s 1933 technique).

2. A promise to increase the money supply at a slower rate, from now until the end of time.

3. A lower price of NGDP futures contracts (which would first have to be created.)

4. Appointing a crazy hawk like Bob Murphy to be head of the SNB.

Basically, you need to combine a lower interest rate with something else that creates the expectation of tighter money going forward.

It’s not a question of whether the Keynesians or the NeoFisherians are right—I don’t agree with either group. It’s a question of which types of monetary policy shocks produce which results. I see three interesting cases:

1. The Keynesian case: In this case, an easy money policy causes a reduction in both short and long-term interest rates. Inflation tends to rise.

2. The NeoFisherian case: In this case, a tight money policy causes a fall in short and long-term interest rates. Inflation tends to fall.

3. The Monetarist case: In this case, an easy money policy causes short-term rates to fall and long-term rates to rise. Inflation tends to rise.

As soon as you are able to visualize the monetarist case as being a hybrid Keynesian/NeoFisherian case, you know you are on the right track. If you see the monetarist case as being short run Keynesian and long run NeoFisherian, then you “get it.” If not, reread the post.

PS. I’ve already indicated that January 2015 in Switzerland was a NeoFisherian case. I’d add that the January 2001, September 2007 and December 2007 Fed FOMC policy announcements were all Monetarist cases. Short and long rates moved in opposite directions. There are also lots of Keynesian examples, but I can’t recall one at the moment.

PPS. I’ve simplified things by assuming that central banks normal lower rates by open market purchases, that is, an increase in the base. They can also reduce market interest rates by lowering the tax on bank reserves, i.e. by lowering IOR. Nothing important changes in this case, but it’s even harder to see the irrelevancy of interest rates when monetary policy shifts from base supply control to base demand control.

PPPS. I may turn this post into a paper, so I’d appreciate any serious feedback.