Stop predicting recessions!

Last year, lots of people said the Australian miracle would finally come to an end. I had commenters mocking me for arguing that Australia wasn’t a bubble. They insisted that the bubble was already bursting. (I wish you guys would come back to my comment section—I miss you.)

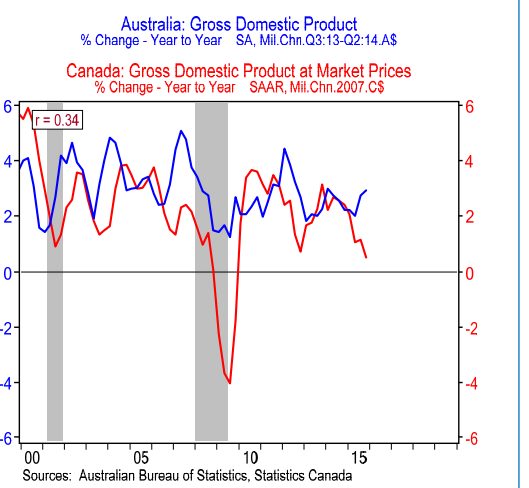

Now we are well into 2016, and the Australian economy is surging:

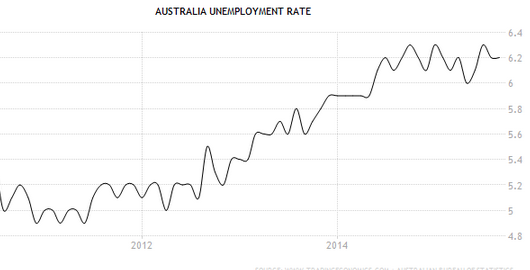

Australian business confidence jumped and an employment gauge in the survey surged to the highest in almost five years, signaling a healthy job market and reducing the likelihood of an interest-rate cut. The local currency gained.

The sentiment index doubled to six points last month, according to a National Australia Bank Ltd. survey of more than 400 firms conducted March 23-31. The business conditions gauge — a measure of hiring, sales and profits — climbed to 12, matching the highest level since before the 2008 global financial crisis. The employment index jumped four points to five, its best result since 2011.

“This is an especially good result in the context of a downbeat global economic outlook,” said Alan Oster, chief economist at NAB. “Low interest rates and a more competitive currency, even given recent strength, are expected to remain key drivers domestically. Consequently, our outlook for the economy remains unchanged — and with the non-mining recovery expected to progress further, monetary policy is likely to remain on hold for an extended period.”

Australia’s economy is proving resilient in the shadow of recent financial turbulence in China, negative interest rates in Japan and Europe and weaker commodity prices that have combined to increase global risk. The Reserve Bank of Australia cut rates to a record-low 2 percent in May last year in an easing cycle designed to cushion the economy from unwinding mining investment and encourage services industries to pick up the slack.

While gross domestic product grew a robust 3 percent last year and the unemployment rate has fallen to 5.8 percent, the Australian dollar has rebounded more than 10 percent since mid-January.

Last Australian recession—1991.

Funny how countries that maintain adequate long-term NGDP growth don’t seem to have problems with the zero bound. I wonder if the problems in Japan and the eurozone are self-inflicted? (NGDP growth has recently been weak in Australia, due to lower commodity prices, but the long-term expected trend is high enough to keep interest rates above zero. That trend rate remains well above European and Japanese levels.)

When the Chinese stock market crashed last summer, lots of commenters mocked my claim that China was doing fine, and insisted that it was entering a recession. This month the consensus forecast for 2016 GDP growth in China (private forecasters) rose from 6.4% to 6.5%. Even accounting for data problems, most experts think growth is at least 5%. In an economy with a flat labor force, 5% is not too bad. Retail sales growth is still running at double digits, and exports are picking up, although by less than this FT story suggests:

China reported stronger than expected trade data on Wednesday, the latest sign of a tentative revival in fortunes that paves the way for Friday’s release of first-quarter economic growth.

Exports surged 18.7 per cent in renminbi terms in March over the same month last year, after declines in both January and February. Imports also stabilised, dropping just 1.7 per cent compared with an 8 per cent fall in February.

In dollar terms, exports rose 11.5 per cent while imports fell 7.6 per cent for the period, reflecting the renminbi’s recent rise. The currency has gained 1.9 per cent against the dollar over the past two months.

China’s export sector has been buffeted by the slowdown in global trade, the dollar value of which has been shrinking since 2012 largely because of the slump in international commodities prices.

The International Monetary Fund this week warned that the world risked a “synchronised slowdown” but highlighted China as a rare bright spot among major economies. Chinese officials have been working to counter international investors’ increasingly negative outlook for the country’s economy.

Their cause has been boosted by a slew of better than expected data releases, including March inflation figures that showed producer price deflation had moderated.

This contributed to the IMF’s decision to revise upwards its forecast for Chinese economic growth this year, to 6.5 per cent from 6.3 per cent. At last month’s meeting of China’s parliament, Premier Li Keqiang projected economic growth of 6.5-7 per cent for 2016.

“China’s commodity imports should see further improvement soon,” said Zhou Hao at Commerzbank.

“Rare bright spot” doesn’t sound like a Chinese recession.

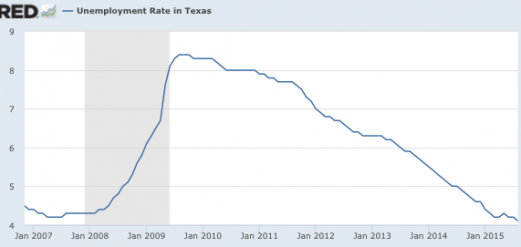

When I hear constant predictions that the Chinese bubble will burst any day now, I’m reminded of Redd Foxx. People need to stop predicting recessions, because recessions are unforecastable. The IMF has predicted zero of the past 220 negative growth periods between 1999 and 2014. This shows that the IMF is smart. They know that the most likely outcome is growth, and hence they predict growth. So do I! Recession predictions also have a corrosive effect on economics as a science. These predictions lead non-economists to believe that economists should predict recessions, and give undeserved reputational points to lucky permabears.

Peter Schiff said back in January that the US would have a big recession this year. If we don’t have a recession this year, people will forget Schiff’s false prediction, as well as false predictions of major crises in the US in 2015 and 2013, and recall his correct prediction of the 2008 recession. (Insert broken clock analogy here.) Whenever I hear that someone has accurately predicted a recession, my evaluation of that person declines. Economists should not be trying to predict recessions; the point is to prevent them. That’s why we need NGDPLT.

PS. If you have trouble with me praising the IMF being zero for 220, consider this analogy. If I’m standing next to a statistician at the roulette wheel, and he predicts the ball will not land on the green numbers (36 out of 38 odds) for each of 220 spins, then I will assume he’s a good statistician. If he occasionally predicts the ball landing on the green (2 out of 38 odds), I will think less of his statistical skills, even if it does land on the green.

HT: James Alexander