Are higher inflation rates inherently less stable?

Vaidas Urba directed me to a very interesting talk by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the European Central Bank. Here’s one item that caught my eye:

Increasing the inflation target real interest rates could then be effective to eliminate negative output and unemployment gaps. These benefits of a higher inflation target can be outweighed by the broader costs of higher inflation, depending on the chosen level. Historically, relatively higher inflation has usually been associated with more volatile inflation.[30] Moreover, the ECB and many other inflation-targeting central banks have shown that other monetary policy tools are available when interest rates cannot be lowered further.

It’s true that the availability of alternative tools makes a higher inflation target unnecessary, but the first argument is a bit misleading. While its true that “Historically, relatively higher inflation has usually been associated with more volatile inflation”, this isn’t actually relevant to the debate over whether the inflation target should be set at 2%, 3% or 4%. Yes, inflation was both higher and more volatile during the 1960s-80s, but inflation was lower and more volatile during the gold standard era.

The greater stability of inflation since 1990 is due to the fact that central banks have started targeting inflation, whereas there was no consistent inflation target under either the Great Inflation or the gold standard. Inflation will be more stable when it’s being targeted, regardless of whether the target is set at 2%, 3% or 4%. Now if you are talking about an extremely high target, say 17%, then I’d expect more volatility, as it’s unlikely the next government or central bank head would agree with that sort of specific number. The real issue is not how high the target is, but rather the degree of consensus. Maybe there is currently more consensus around 2% than 3%, but if the zero bound continues to be an issue then that consensus may reverse in the future.

The discussion also mentions NGDPLT, but doesn’t really offer any useful analysis of that proposal.

David Levey directed me to an interesting Vox essay by Athanasios Orphanides, which compares the debt situation in Japan and Italy:

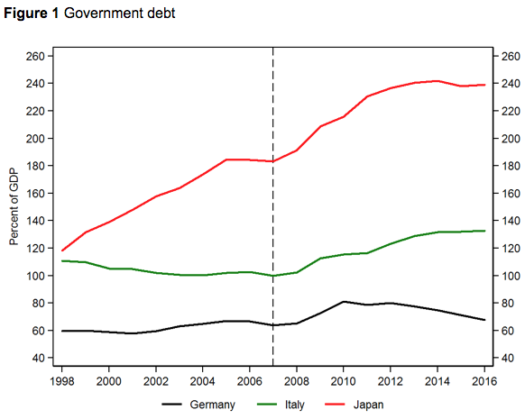

For Japan, the dramatic rise of the debt ratio before the crisis reflects the lack of nominal growth. While the long-term government bond yield appeared to be low (consistently below 2%), nominal GDP growth was even lower (about zero, on average). The adverse debt dynamics worsened after 2007, with the recession following the Global Crisis. Part of the problem was overly tight monetary policy: policy rates were constrained by the zero lower bound (ZLB), but the Bank of Japan was reluctant to employ the required QE policies. However, since 2013 the Bank of Japan has embarked on a decisive QE programme which has simultaneously boosted nominal GDP growth and depressed long-term government bond yields. Since September 2016, as part of its ‘Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with Yield Curve Control’ policy, the Bank of Japan has communicated explicitly its intention to keep the 10-year yield on government bonds close to zero and short-term interest rates negative until inflation rises to 2%, in line with its definition of price stability. This monetary policy has stabilised Japan’s debt dynamics and has provided the Japanese government more time to implement structural reform measures and complete the fiscal adjustment needed to bring its primary deficit under control.

Abenomics has modestly boosted inflation in Japan, but the rate remains below the BOJ’s 2% target. In another sense, however, the policy has been a big success. Unemployment has fallen to 2.8%, NGDP growth has accelerated, and the debt ratio has stopped rising. Japan is no longer on the road to bankruptcy.

Abenomics has modestly boosted inflation in Japan, but the rate remains below the BOJ’s 2% target. In another sense, however, the policy has been a big success. Unemployment has fallen to 2.8%, NGDP growth has accelerated, and the debt ratio has stopped rising. Japan is no longer on the road to bankruptcy.

That’s why I favored the monetary “arrow” of Abenomics, and I’m pleased to see even a partial success. In contrast, Italy lacks its own currency and will have to combine fiscal austerity with supply-side reforms to solve its problems. That’s much tougher to achieve.

PS. Hester Peirce is my colleague at the Mercatus Center, where she focuses on financial regulatory issues. In this link, she’s on a panel with Ben Bernanke, discussing Dodd-Frank provisions such as the “orderly liquidation authority”.

Tags:

6. June 2017 at 08:22

Brazil has a higher inflation target and has had higher inflation volatility even when it has an explicit inflation target.

6. June 2017 at 08:33

Hello,

I am a new commenter on this blog. I’ve been reading these posts for the last few days, and am very interested in the unique take on economics and monetary policy.

It is something I believe is sorely lacking from the normal economic discussions and news groups (TE, FT, WSJ, etc.).

In response to the post here, I have a few questions and a few observations.

First, my understanding of economics and what is possible in monetary policy has changed significantly over the last 6 years. Since I am much younger than Mr. Sumner, I’ve only been paying attention to monetary policy/economics since around 2011. Nonetheless, I was raised on a rather conservative and tight money/low inflation, what you borrow you must pay back, mentality.

I remember clearly the December 2012 election that brought Abe his majority in Japan. I also remember clearly the credit crisis and debt crisis in the EU. Furthermore, I remember millions of endless predictions of a catastrophic Chinese economic crash (because surely everyone mimics the USA, right?)

My impression of Abenomics, and the three arrows, was that it was simply a restart of the Keynesian policies of his LDP predecessors since 1990. Maybe it would provide a short term boost, but his loose monetary policy and huge fiscal stimulus would have to be repaid. Essentially, stealing future growth for current growth.

Yet, that is not what has happened. My opinion of the LDP and Abe has become much more negative even though my predictions of continued economic stagnation have been proven wrong. Abenomics has been partially successful, and that’s far better than Abe’s predecessors’ solutions.

To keep this from getting too long, my question is… since the monetary policy of Kuroda is essentially debt monetization, what is the cost of his policy? Is there no cost at all? Maybe the policy is so correct, and Japan’s economy is so below potential, that the policy has no future cost.

Furthermore, how come the NGDP growth has reached 2% annually since 2015 (and a record NGDP), yet the GDP deflator is only up 5% since 2013? I just don’t get how this is possible.

Likewise, China has a (roughly) similar debt situation as Japan in the 90’s. Almost all the “bad” debt is between the SOE’s and the state banks. Could China enact a similar policy as Japan to monetize this SOE debt in exchange for SOE restructuring?

My final observation is that Italy, Spain, and many southern European nations are in a far worse position than Japan, Korea, or China. I agree with your view. Their lack of independent monetary policy or an independent currency has severely constrained their NGDP growth and made them incapable of either increasing fiscal spending or lowering debt burden costs on their economy.

Maybe if a monetary policy is so correct for the problem it is meant to address, the net benefit to the economy far outweighs any inflation/moral hazard issues. We learned so much from the monetary failures of Japan. It seems we can also learn from their monetary success as well.

6. June 2017 at 08:43

Oh, and I hope everyone reads this story. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05-24/japan-emerges-as-a-surprise-growth-market

Some good quotes from it:

-“There’s been far more success for the overall Abenomics agenda than generally recognized,” says Jonathan Garner, chief Asia and emerging-markets equity strategist at Morgan Stanley in Hong Kong, who has Japan as one of his top market picks. He anticipates both nominal growth and wages to strengthen further, finally spurring inflation—“the last piece of the jigsaw puzzle to fall into place.”

-So is it morning in Japan again? That would probably be overstating things. “I’ve never come across a country which talks itself down as much as Japan,” says Varney, the Legoland developer. “It’s still a remarkable success story.”

So, finally, the sun may have at least stopped setting.

Overall, my impression is that Japan’s rise has been almost purely driven by monetary policy and not economic reforms or significantly increased fiscal spending. It just shows how powerful proper monetary policy can be.

NGDP is up about 20% since 2012. On a more sober note, RGDP is only up about 7%.

6. June 2017 at 08:48

Jose, Good point. However:

1. The target was adopted recently, in 2005.

2. The target range is 2% to 7%, an unusually wide range.

3. Brazil’s economy is far more unstable than the US or Eurozone. That matters if it is a flexible inflation target. The major overshoot occurred during the severe recession of 2015–16, when an overshoot is appropriate under flexible inflation targeting.

6. June 2017 at 08:54

Alec, I do not believe Japanese NGDP is up 20% since 2012, I think it’s closer to 10%.

It wasn’t “Keynesian” policy, it was monetarist. Fiscal policy has been tight.

I don’t view it as debt monetization, although some might view it that way. Debt monetization occurs when you buy positive interest government bonds with zero interest cash.

6. June 2017 at 09:20

Sumner, I just did the calculations and it is about 10%. My apologies.

And yes it was not Keynesian policy. I just initially thought it was in 2013 during the Abenomics buzz since Abe promised immense fiscal spending increases and lower taxes. Instead he raised taxes and kept fiscal spending about the same. On the whole, Abenomics does not really exist. It is Kurodanomics monetarist policy.

Finally, yes it is not technically debt monetization. Nonetheless, it is pretty darn close. What are you thoughts on Japanese monetary policy since late 2012?

Do you have a large blog post on the policy?

6. June 2017 at 11:42

Sumner: “The greater stability of inflation since 1990 is due to the fact that central banks have started targeting inflation”

No, that’s secular strangulation (esp. pronounced after the DIDMCA of March 31st 1980 which laid the legal basis for turning 38,000 financial intermediaries into 38,000 commercial banks, viz., that ill-conceived Congressional regulation which precipitated the S&L crisis, that economic mis-conception that there is no difference between money and liquid assets).

Secular strangulation accelerates not only with a FOMC induced business cycle (contrary to the Austrian theory), but also with more developed countries. And the remuneration of IBDDs exacerbates this blatant theoretical and empirical accounting error.

Martin Wolf’s (chief economics commentator at the Financial Times) “structurally deficient aggregate demand” is incremental (Alvin Hansen’s 1938 chronic condition of “sagging investment & buoyant savings”). Thus, the excess of savings over investment outlets will continue. And bond prices will be lower in the latter part of 2018, esp. after February 2018 (as supply side factors, e.g., decelerating inflation, predominate), given that contrary demand side factors (fiscal deficits), remain containable.

The rate-of-change in money flows determines the roc in both R-gDp and inflation. I.e., money flows are more than merely robust. The distributed lag effect for money flows, volume Xs velocity, have been mathematical constants for over 100 years (so they must actually be orbital constants). The correlation coefficient is +1 – indeed perfect.

Targeting N-gDp caps real output and maximizes inflation. I.e., there isn’t a single professional economist alive today that understands macro-economics.

– Michel de Nostredame

6. June 2017 at 13:43

Yes, Prof. Sumner, but the experience in Brazil is that higher inflation brings demands from society for some sort of indexation. In regulated economies regulators are tempted in turn do create different indexes to adjust certain important prices. Energy prices in Brazil are a good example. But under this setting, higher inflation ends up creating imbalances when the various indexes diverge. What we saw happening in Brazil is that from time to time these imbalances become unbearable and their adjustment is painful, and recessionary. I think that the higher inflation proponents forget that higher inflation may and eventually will disorganize relative prices in the economy.

6. June 2017 at 16:18

I would like to see a treatment of Japan’s QE program. Is this in effect a helicopter drop?

What is the meaning of national debt if the Bank of Japan owns 43% of it and rising?

If one contends that Japan’s national debt still exists, then would have Japan been better off printing yen and buying foreign national bonds?

Japan could collect interest on $10 trillion of foreign bonds and cut domestic taxes by an equivalent amount.

6. June 2017 at 17:13

Alec, I have lots of posts. Use my search box with terms like Abe, BOJ, Kuroda, etc.

Jose, I don’t think Brazil’s experience has anything to say about inflation targeting in advanced economies. We had 4% inflation from 1982-90, without the problems you cited. Nobody is advocating Brazilian-style inflation.

7. June 2017 at 11:19

@ Benjamin Cole:

I don’t watch foreign markets (Japan et. al.), but you can rightly assume more savings are ensconced and impounded relative to the U.S. No need to watch other nations when the U.S. is on the brink. Total credit market debt, government, business, household, foreign, and financial debt is so high in terms of available taxable resources, disposable income of consumers and business income, we dare not have another severe recession:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/W006RC1Q027SBEA

We are currently in a balancing act that cannot long endure; nor can we stimulate the economy for fear of higher rates of inflation and interest rates. Never has our country faced such a dilemma. And we have the economists to blame. We have not been invaded; we have never had reparations imposed on us; and unlike Japan, our resources are far from being exhausted. It is also unprecedented that a country could have chronic foreign deficits (currently 1/2 trillion annually), and not have its currency drop sharply in the foreign exchange markets.

All that Armageddon requires is that the credit of the U.S. Government be put in jeopardy or that the payment’s gap is no longer filled by foreign investment.

Inflation cannot destroy real property nor the equities in these properties. But it can and does capriciously transfer the ownership of vast amounts of these equities thus unnecessarily accelerates the process by which wealth is concentrated among a smaller and smaller proportion of people, viz., N-gDp targeting (which caps the *real* output of goods and services and maximizes inflation). Economists being wordsmiths call this stagflation.

The concentration of wealth ownership among the few is inimical both to the capitalistic system and to democratic forms of government. A financial oligarch and a government of, by, and for the people, simply cannot exist side by side. And the exacted toll cannot be measured on the lives of people in terms of the average per capita income, or any other statistic. And the evidence of inflation, contrary to the conventional wisdom, cannot be conclusively deduced from the monthly changes in the price indices.

Calculating inflation on a year-to-year basis minimizes, over time, the rate of inflation since the rate is being calculated from higher and higher price levels and higher bases (the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers increased 0.2 percent in April, but in terms of the BLS 82-84 base year for the CPI it is 250 percent – an absolute and substantial increase).

To the many people living on relatively fixed incomes, including those living paycheck to paycheck, the present method of calculating inflation grossly underestimates the increasing hardships of this group, even in the current period of “low rates”. In absolute terms, each year confronts all of us with a higher and higher level of prices with no end in sight.

The evidence of inflation, contrary to the conventional wisdom, cannot be conclusively deduced from the monthly changes in the price indices. The price indices are passive indicators for the average change of a group of prices. They do not reveal why prices rise or fall.

Only price increases generated by demand, irrespective of changes in supply, provide evidence of inflation. There must be an increase in aggregate demand which can come about only as a consequence of an increase in the volume and/or transactions velocity of money. The volume of domestic money flows must expand sufficiently to push prices up, irrespective of the volume of financial transactions, the exchange value of the U.S. dollar, and the flow of goods and services into the market economy.

10. June 2017 at 07:07

Free-market clearing rates (one year CMT rates), are already @ 1.20%. Rhetorically, what’s another .05%? “The Fed follows the market”:

http://bit.ly/2t47cy2

A preemptive inflation strike is already in place for 2018. Any policy rate hike will cause money velocity to fall, short-circuit extant money flows, produce an inversion of the yield curve, and result in an economic downturn in the 2nd qtr. of 2018. The stagflationist (advocates of equilibrium interest rates, R*, and targeting N-gDp parameters), “suggest a higher inflation target” (Phillips curve rendition).

Dean Baker

Laurence Ball

Jared Bernstein

Heather Boushey

Josh Bivens

David Blanchflower

J. Bradford DeLong

Tim Duy

Jason Furman

Joseph Gagnon

Marc Jarsulic

Narayana Kocherlakota

Mike Konczal

Michael Madowitz

Lawrence Mishel

Manuel Pastor

Gene Sperling

William Spriggs

Mark Thoma

Joseph Stiglitz

Valerie Wilson

Justin Wolfers

http://bit.ly/2s67De9

10. June 2017 at 10:58

Hey Scott, I just thought you’d find this interesting:

Danish Government Seeks Income Tax Cuts to Counter Overheating https://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2017/06/09/business/09reuters-denmark-tax.html?mcubz=1&_r=0

It shows that supply side policies are more likely to be enacted when monetary policy is loose enough to attain full employment.

10. June 2017 at 12:39

What’s really funny is that an increase in IBDDs is contractionary, not expansionary. Of course the net preciptitation initally depends upon the trading desk’s counterparty. However subsequently, it’s always contrationary.

11. June 2017 at 05:23

Tyler noticed:

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2017-06-09/meet-22-economists-want-kill-your-purchasing-power

11. June 2017 at 05:25

Lewis, Very interesting.