Does my view of the recession fit the data?

Arnold Kling has responded to my recent critique of reallocation theories. He begins by pointing out (correctly) that my housing start data is not optimal, as it lags a few months behind housing activity. But we both agree there is still something of a mismatch between the timing of the housing bust and the severe phase of the recession. Instead, Kling focuses his attention on other alleged weaknesses in my argument. Not surprisingly, I will deny my argument has any serious weaknesses.

Here is Kling, and then Ed Leamer:

The other point I would make is that it is unfair to compare almost any variable to employment over the past 2+ years. That is the point of Brad DeLong’s post. In terms of explaining weak employment, the aggregate production function approach falls short also. Or, as Ed Leamer puts it,

“the national job markets certain structural problems that have created a mismatch between what employers are looking for and what unemployed workers have to offer. These structural issues include the loss of manufacturing jobs to a variety of “competitors” both technological (robots, microprocessors) and human (foreign workers and recent immigrants willing to work for less) and the housing crisis that continues to jeopardize the construction sector. Unlike in previous recessions, Leamer opines, workers today are not easily returning to the jobs they lost and as a result the economy must find a way to create jobs for millions of workers whose skills lend themselves more suitably to manufacturing and construction.”

I see no problem here at all. The drop of GDP, both real and nominal, was one of the most severe since the Great Depression. If in 2007 you had told me nothing but the future path in NGDP and RGDP, I would have said that tight money sharply reduced AD and created a severe recession. I would have predicted some of the highest unemployment of the entire post-war period. There is no mystery at all as to why so many people are without work. The mystery is why RGDP fell so sharply. Given that fall, you’d expect high unemployment. None of this has anything to do with technological progress. Our Econ 101 models tell us that when AD shifts sharply left you will get high unemployment, and that’s exactly what happened. If we had more AD, most of the workers would return to service sector jobs. A few would return to manufacturing and construction. There has been a long term shift from manufacturing to services, but that shift is unrelated to the business cycle, and it occurs without any rise in the unemployment rate, as long as NGDP growth is adequate.

Then Kling claims that there are 5 outstanding issues, and that I have only addressed numbers 1 and 5:

1. The big drop in GDP occurs after most of the drop in home construction.

2. The financial indicators, including risk spreads, stock prices, and bank profits, recover fairly nicely, but real GDP does not.

3. Whatever recovery shows up in GDP is not matched by a recovery in employment.

4. A simple linear Phillips Curve of the form inflation = 7.0 – unemployment would say that we should have prices falling at an annual rate of 2 percent now, rather than rising. (Admittedly, this is not a powerful point, because inflation can be measured in various ways, and nobody said that the Philips Curve was linear.)

5. In my recollection (which may be wrong), steep recessions tend to be followed by brisk recoveries. Not so this time.In short, there is a lot about this recession that I think is puzzling. Sumner has a story for (1) and (5), but it is hard to reconcile with (2) and sidesteps (3) and (4).

I think that the behavior of macroeconomic variables in this recession poses some awkward issues for everyone.

Let’s take #3 first, by far the easiest. In the 1983-84 recovery, Volcker allowed 11% annual NGDP growth over the first 6 quarters. RGDP rose 7.7% annual rates and inflation rose about 3.3%.

This time the Fed allowed closer to 4% NGDP growth over the first 6 quarters of recovery, and the split was close to 3% real and 1% inflation. I’d say those splits are similar, the difference is the Fed simply didn’t provide enough fuel to allow for fast RGDP growth. It’s implausible to expect 8% RGDP growth if doing so requires negative 4% inflation.

Once we understand why RGDP growth has been weak during the recovery, the employment numbers make lots of sense. The trend rate of growth is around 2.5% to 3%, and you’d expect no change in the unemployment rate if growth is at trend. Our growth may have been a tad above trend (it’s hard to know for sure) but it’s also true that unemployment has fallen slightly since the 10.1% peak in 2009. No significant mystery to be solved, although I acknowledge that each recession is slightly different in terms of Okun’s Law, Beveridge curves, etc.

Number four is slightly tougher. It does seem that Phillips curves flatten out a bit near zero, and we don’t know exactly why. There are theories such as the alleged reluctance of workers to take nominal pay cuts. We’ve also seen a big rise in the minimum wage rate (40% over a couple years) and the 99 week unemployment benefits. I don’t know if these made the labor market slightly less flexible, but it’s possible. But even without these factors I’d expect the Phillips Curve to flatten at very low inflation rates. Other countries observe similar patterns. “Further research is needed . . . ”

I’m not as puzzled by #2 as Kling. Stocks are still far below their 2007 peaks, while RGDP has returned back to roughly pre-recession levels. So at first glance it looks like Kling has things exactly backward. In fairness, RGDP is still well below the trend line, and there is still an output gap, albeit not as large as crude trend extrapolation would suggest (I’m not that naive!) On the other hand stocks also trend upward over time, so if stocks are 18% below the peak, they may be 28% below the trend line. That’s a lot, and not inconsistent with the effects of a big recession with a slow recovery. And of course there are still lots of debt problems out there, the foreclosure mess, a continuing overhang of commercial real estate problems, state and local government distress, etc. It’s not like the financial system is back to normal. Also recall that many US companies are earning a large share of their profits overseas, and the developing world is growing very fast. That explains some of the strength in equities.

The hardest thing for me to explain is not the level of equity prices, but the rapid increase since March 2009. And the same applies to the health of our financial system. The only hypothesis I can think of is that in March 2009 investors feared an outright depression, and this worry sent asset prices to (what is now known as) unjustifiably low levels. And these falling asset prices severely hurt the financial system. Banks bounced back somewhat when an economic recovery in Asia, and then the US, showed that an outright depression was unlikely.

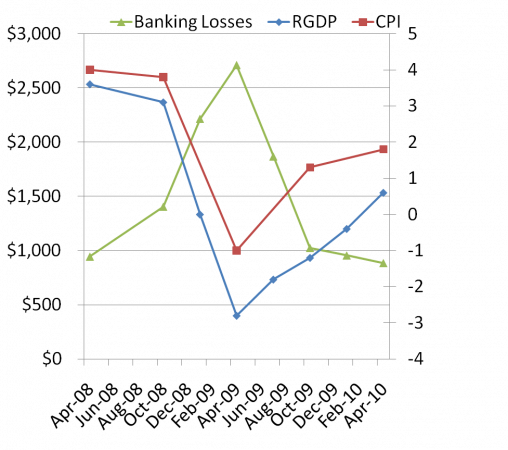

Is there evidence for this view? The IMF does periodic forecasts of RGDP growth, inflation, and total banking system losses for the US. The following graph shows that IMF estimates of banking losses got much worse until early 2009, and then much better. And that pattern is inversely related to the IMF’s estimates of growth and inflation over the two year period from 2008 to 2010. Note how bearish these IMF economic projections were at the low point.

Note: Left scale is total estimated banking losses in billions. Right scale is total estimated RGDP and price level growth between 2008 and 2010.

Tags:

15. January 2011 at 08:49

“The only hypothesis I can think of is that in March 2009 investors feared an outright depression, and this worry sent asset prices to (what is now known as) unjustifiably low levels.”

Wait, isn’t your argument that the market responded poorly when fiscal stimulus happened (and thus less monetary) and did better when monetary happened?

15. January 2011 at 10:11

Scott: You´ve finally won him over! BEWARE!!!

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/01/15/zirp-and-zmp/

15. January 2011 at 11:20

“The hardest thing for me to explain is not the level of equity prices, but the rapid increase since March 2009. And the same applies to the health of our financial system. The only hypothesis I can think of is that in March 2009 investors feared an outright depression, and this worry sent asset prices to (what is now known as) unjustifiably low levels.”

Yes, that seems the most plausible explanation. Imagine a counter-factual in which stocks had only dropped 17% in 2008 and then drifted sideways for the next 2.5 years, putting us exactly where we are now. Would as many people suggest there wasn’t an AD problem in that scenario? It seems many commentators have been mesmerized by the recent rally in stocks, losing sight of the big picture that they are only playing catch-up — and haven’t yet caught up.

15. January 2011 at 11:20

BTW, this from Scott Grannis, blogger of Califia Beach, a good econ blog:

“Scott Sumner””a rising star in the economics profession, in my estimation””has penned some insightful comments on the subject of commodity prices and monetary policy, and he is one of the very few competent advocates of the theory that the Fed should target nominal GDP instead of inflation.”

A rising star!

Grannis is old enough to use the expression “penned.” Today, we should say “Sumner digitized some insightful comments.”

15. January 2011 at 11:29

Scott Sumner re your Los Angeles trip:

No, I only advised you cancel as you blogged that disaster consistently follows your wake as you visit other cities or regions. Stong correlations suggest causal effects.

I live in Los Angeles, and do not want calamity to darken our fair metropolis.

15. January 2011 at 12:49

[…] agree with the first part, where Tyler discusses the weak labor market. I’ll simply link to my previous post, which explains why. I do agree that our problems are partly real/structural/supply-side. But […]

15. January 2011 at 13:35

Morgan, I said fiscal stimulus didn’t help, not that it caused the crash.

Marcus, Thanks, I now have a post mentioning that.

Dirk, That’s a good point.

Benjamin, Thanks, It’s always better to be a rising star that an over the hill star

Oh, you live in LA. I was wondering why I should care if there was a disaster after I left. 🙂

16. January 2011 at 13:37

[…] agree with the first part, where Tyler discusses the weak labor market. I’ll simply link to my previous post, which explains why. I do agree that our problems are partly […]

16. January 2011 at 18:29

i can say that, as an investor, the high loss number the IMF was quoting at the peak was certainly scary to me.

that number, if i remember correctly, included both the US and europe. given that their estimate is less than $1T now, i’d imagine that it includes only losses still pending, or does it include all losses on credit contracted by ’08?

i am sure however that if people believed a $1T loss number in ’08 or ’09 — even if that was all in the US — there would have been no panic. those levels of loss are high but manageable.

16. January 2011 at 18:33

q, No, all of the figures are US only, and all refer to the entire crisis, from the beginning in 2007 to the end (I forget which year they used.) So it really does show changes in the perceived severity of the crisis.

17. January 2011 at 04:08

Scott…. You said:

1. QE works. So, to you TARP works.

2. Fiscal doesn’t work.

3. When fiscal happens, Fed cuts back on monetary.

SO, WHY did GDP fall 8% below trend?

Well according to you there has been less Monetary, because there was Fiscal.

And as such, you pin at least some of the fall on the Fiscal.

Well how much of the fall?

Well according to you, it doesn’t take MUCH Monetary to get the market rallying and to see real growth.

Maybe Obama doesn’t do $1T Stimulus, state’s make hard cuts a while ago (which is good, cuts into sticky wages), and the Fed tushes in with say twice as much QE, as before.

Given that the multiplier for fiscal is below one, right?

So, please tell me what part of my logic fails. Where do you deviate?

17. January 2011 at 19:48

Morgan, Yes, I’ve argued we might be better off today with no stimulus. And I support the British government cuts.

18. January 2011 at 08:52

Have you ever been unemployed and, relatively, lacking in skills?

“There are theories such as the alleged reluctance of workers to take nominal pay cuts. We’ve also seen a big rise in the minimum wage rate (40% over a couple years) and the 99 week unemployment benefits. I don’t know if these made the labor market slightly less flexible, but it’s possible.”

You are so naive sometimes. To paraphrase a quote from somewhere ‘you will get exactly as many unemployed as you are willing to pay for’. At the lower end of the employment scale the choice between unemployment benefits and working is often pretty straightforward, especially in a big shakeout when the vigilance of the benefits officers is swamped by claimants.

Why is it only an “alleged” reluctance, are public sector workers ever so well managed that paycuts are ever offered? It is one of the big problems of a huge public sector that wages will definitely get stickier on the downside than they “allegedly” would be in a 100% non-public sector environment (companies, self-employed, charities, foundations doing the job of the public sector).

18. January 2011 at 15:29

James, It seems like you agree with me, so are we both naive?

19. January 2011 at 13:57

Maybe you were being ironic when you said “alleged reluctance” and “slightly less flexible”. I took you to mean that you didn’t think workers would take wage cuts, and that unemployment insurance didn’t make the labout market significanly less flexible. Are all your comments ironic?

You really are in fact worried about inflation getting out of control and destroying people’s money savings faster than alleged gains in investment returns, or interest rates rising at some point to above inflation and thus protecting people’s money savings from the inflation. Or so much RGDP around that everyone’s wealth, including the money savers, will rise up wonderfully. A sort of Keynesian/Monetarist fairy tale.

20. January 2011 at 14:48

James, I can’t understand when you are talking about your own views, and when you are talking about mine. Try to be less sarcastic and just state clearly what you believe.

If you are saying 99 weeks UI increases unemployment, then we agree. Ditto for minimum wages and sticky wages.

3. February 2011 at 11:53

[…] dollar amount they’re going to receive this month and the next. As Scott Sumner has been pointing out, nominal growth was kept at a steady 5% clip year in and year out, a number which US businesses […]

3. February 2011 at 11:58

[…] dollar amount they’re going to receive this month and the next. As Scott Sumner has been pointing out, nominal growth was kept at a steady 5% clip year in and year out, a number which US businesses […]