Gavyn Davies on the Fed meeting

Here’s Gavin Davies of the FT:

The startling recovery in risk assets in October – global equities rose by 11 per cent during the month – was triggered mainly by reduced pessimism on the eurozone’s debt crisis, but was probably also helped by easier monetary policy from several of the major central banks. As usual, the Federal Reserve has been in the vanguard of this action, and further measures are expected from the FOMC when it meets on Tuesday and Wednesday.

There have been calls for major innovations, such as the introduction of a target for the level of nominal GDP, but the Fed has given little indication that it is ready for anything quite so drastic. Much more likely are some further modest steps to improve the communication of the Fed’s thinking on the future path of short rates, with the aim of keeping long rates as low as possible. And there might also be some more purchases of mortgage backed securities.

This certainly caught my attention, as there were three high profile endorsements of NGDP targeting recently; Romer, Krugman and Goldman-Sachs. And there is only one person who was cited or linked to in all three statements. I’m tempted to resurrect my connecting the dots post, but can’t really do so in good faith. Davies is right; NGDP targeting is not going to be adopted at this meeting. Indeed something that important ought to be widely debated first. And that hasn’t yet occurred. Still, I’d hope to see a mention that they are at least discussing the merits.

I do think Davies might be right about monetary stimulus chatter having some effect on equity prices recently, but I don’t see any firm evidence that would make that more than a conjecture. In any case, any influence I have on that debate is an order of magnitude lower than the specific topic on NGDP targeting.

Davies continues:

Although the idea has merit, and may well be discussed by the FOMC in future, it is not likely to emerge from this week’s meetings. Ben Bernanke has discussed many radical actions for monetary policy in the past, notably relating to Japan a decade ago, but I do not recall him ever giving much attention to a nominal GDP target. He has consistently focused on the advantages of adopting a clear and consistent target for the rate of inflation (note, not the level of prices, but their rate of change, so past shortfalls would not need to be restored), and in a recent speech on 18 October he said the following:

“As a practical matter, the Federal Reserve’s policy framework has many of the elements of flexible inflation targeting…The FOMC is committed to stabilising inflation over the medium term while retaining the flexibility to help offset cyclical fluctuations in economic activity and employment.”

A couple points. Davies is right about Bernanke’s focus on inflation, but Bernanke actually has recommended the level targeting of prices. Of course it was for Japan, not the US. It’s too bad Bernanke has no interest in NGDP targeting, as it would achieve the objective laid out in that quotation far better than inflation targeting. Indeed that Bernanke quotation is a textbook argument for NGDP targets.

He went on to argue that inflation targeting had proven its worth in stabilising inflation expectations in both directions in recent years, and he concluded as follows:

“My guess is that the current framework for monetary policy – with innovations, no doubt, to further improve the ability of central banks to communicate with the public – will remain the standard approach, as its benefits in terms of macroeconomic stabilisation have been demonstrated.”

If a 9% fall in NGDP below trend from mid-2008 to mid-2009, which led to massive and costly fiscal stimulus in the desperate hope it would prop up the very same aggregate demand that the Fed is supposed to be controlling is “benefits . . . demonstrated,” I’d hate to see a failed monetary policy. And then there’s the sub-5% NGDP growth during the 27 month “recovery.”

Janet Yellen is particularly important here, since she is in charge of a Fed committee examining the matter. In her speech, she said:

“We have been discussing potential approaches for providing more information “” perhaps through the SEP “” regarding our longer-run objectives, the factors that influence our policy decisions, and our views on the likely evolution of monetary policy.”

The SEP is the Summary of Economic Projections, in which FOMC members give their outlooks for the main economic variables in the years ahead. It seems from Janet Yellen’s guidance that the Fed might decide to beef up this document so that it becomes more explicit about the nature of its long run inflation and unemployment objectives, and about the conditions underpinning its commitment to hold interest rates close to zero until mid 2013.

It is even possible that FOMC members might start to publish their entire expected path for short rates over future years, conditional on their economic forecasts. (Read my lips: no new rate hikes!”) The Chairman has explicitly pointed out that other central banks publish such projections of policy rates, which help influence market expectations of central bank policy.

The idea here would be to increase the confidence of the markets that short rates are intended to remain at zero for a very long time to come, which might in turn reduce long bond yields even further. That would be useful in easing monetary policy slightly, but it cannot be expected to have very much effect when short rate expectations are already so low. More drastic options, like a target for the level of nominal GDP, will have to wait a while.

That doesn’t do much for me. I’d say lower long term rates are more likely to be “evidence that monetary policy remains ineffective,” rather than “useful in easing monetary policy slightly.” The Fed is still a long way from the point where it comes to grips with what actually needs to be done. But at least they are searching for answers.

HT: Richard W.

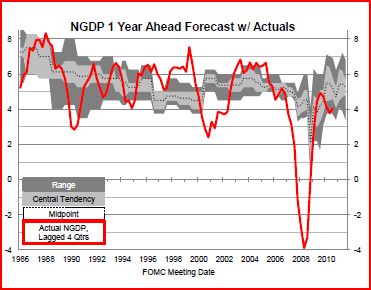

PS. Joshua Lehner just sent me some interesting graphs comparing actual NGDP growth with Fed forecasts at different time horizons. They obviously envision roughly 5% NGDP growth, and just as obviously aren’t doing level targeting. Interestingly, he said the Fed stopped doing explicit NGDP forecasts in 2005, now it’s just RGDP and P. That’s a bad sign.

Update: Josh Lehner send me this post from his blog.

Tags:

31. October 2011 at 16:03

Yet another excellent Sumner post.

Can Ben Bernanke, the brave armchair analyst when safely cloistered in academia, also become the brave leader when in the actual pilot’s seat?

So far, no. But the more Market Monetarism is discussed, the more the Romers, and Krugmans etc. say they like it, the more he will consider it. Kepp blogging, keep writing letters, keep up the buzz.

Market Monetarists should now concentrate on converting the right-wing to the fold (although the right-wing may prefer to stay on sidelines until they get GOP president).

It is odd–with forefathers like Freidman and John Taylor, and with less emphasis on fiscalism, Market Monetarism should be popular with the right.

We just have to swat away the gold-nuts and people with peevish fixations on inflation.

Being a Market Monetarist is like trying to score a touchdown when both teams are trying to tackle you.

Run, Scott “Money Swivelhips” Sumner!

31. October 2011 at 17:00

“Stopped doing exolicit NGDP in 2005”. Curiously thaté Greenspan last year as boss (Bernanke took over Feb 1 2006). Is it a coincidence that until then NGDP followed closely the Level path? Is this relevant to the fact that Bernanke didn´t “notice” NGDP was dropping fast right in his face since early 2008, while he was all concerned about oil, commodities and inflation?

31. October 2011 at 17:15

“Still, I’d hope to see a mention that they are at least discussing the merits.”

It’ll be noted mostly likely in a staff presentation.

Perhaps mention of it when the minutes come out.

31. October 2011 at 17:48

nunes, getting Sumner of sit on Greenspan’s lap is near impossible.

1. November 2011 at 04:22

Hey Morgan, you will enjoy:

http://www.vanityfair.com/business/features/2011/11/michael-lewis-201111#gotopage1

1. November 2011 at 05:05

Stats, yep it was good. Ending was weird. California is f’ed.

1. November 2011 at 05:58

I just want to point out that the latest estimate for quarterly nominal GDP growth, annualized, was 5.0%. The average annualized quarterly nominal GDP growth since October 2009 has been 4.4%, ranging from 3.1% to 5.5%.

This blog began in February 2009. If you assume it took a few months before people noticed, and read, and thought about, and implemented … it looks a lot like the Fed did implement a 5% NGDP target starting in October 2009. Have they been absolutely on target each quarter? No. But is 4.4% really that far from 5.0%, considering that they are having to learn new tricks as they go along? And they are exactly on target now. They exceeded the target for two quarters in a row during 2010.

You might argue that they should make up for the output lost by the recession, to draw their 5% trend line from the peak of the previous business cycle. OK. But if I were learning to ride a bicycle for the first time, would I want my first task to be making up for lost time, or would I want my first task to be learning how to ride at a safe and sustainable speed?

And the peak of the previous business cycle included the fruits of an unprecedented housing bubble, along with an unsustainable global credit bubble that sent a tidal wave of hot money into US financial markets. Perhaps measuring from the peak of an unsustainable collection of bubbles isn’t the most prudent starting point.

If I were on the Fed I could say — yes, we were wrong, we fucked up. But now we are doing EXACTLY what you ask of us, yet you aren’t satisfied, because we haven’t explicitly announced that we are doing EXACTLY what you ask of us. Look at the result, not the minutes.

1. November 2011 at 06:07

Davies is conflating too many things here. The way I see nominal gdp level targeting entering the framework is precisely through the clarification of the 2013 guidance. Undoubtedly, this amounts to a mammoth communications task, but it has entered the fringe of what’s possible given Romer, Krugman, and GS’ endorsements. The doves have been stating in their speeches and in the minutes that the best thing monetary authorities could do now is clarify the future path of policy. That could mean a lot of things, but ngdp level targeting is one of those things.

Some other things to note: Bernanke has never been a hard inflation target-er the way Mishkin was. In general the Fed is not a fan of explicit targets; targets not only mean accountability, but also reduced flexibility to react to new shocks and unusual circumstances (say 0% growth, 5% inflation; they would not like to reveal their hand in such circumstances). The cost-benefit analysis doesn’t add up to explicit targeting for them. Explicit NGDP level thresholds, not targets, is where I see the Fed a year from now. Only after the Eurozone mess gets sorted out one way or the other will it be revealed to policymakers just how deep a hole we are in.

Final point, I think that people screaming for expansionary monetary policy have misjudged the reason for Fed timidity. It has nothing to do with dissension and everything to do with the exit strategy. Right now there are fairly good odds that when the Fed launches into exit mode, they will post a loss…and will have to be funded by Congress in all likelihood. The Fed should technically not care about this when executing monetary policy, but let’s be realistic…

1. November 2011 at 06:13

FYI, Canadian reaction from the Financial Post today:

“Terence Corcoran “” NGDP targeting: the very latest econo-fad

The NGDP targeting debate is heating up, and if you don’t know what the NGDP targeting debates are all about, you are not alone. Slowly, however, the idea is sweeping across the economic swamp. As a Wall Street Journal blog commentary put it last week: “Best to get up to speed as much as possible now, as it is only likely to gain momentum from here.”

The first sighting of NGDP targeting in Canada landed almost two weeks ago, when Liberal MP Scott Brison brought a motion before the Commons finance committee calling for it to hold “at least one meeting before the end of November 2011 to hear from witnesses, such as, but not limited to, members of the C.D. Howe Institute Monetary Policy Council, on whether or not the government of Canada and the Bank of Canada should consider other targets, such as but not limited to, nominal GDP or full employment.”

If you blinked, you missed it: The words “but not limited to nominal GDP” contain the hottest new concept in the world of economics. NGDP stands for nominal gross domestic product and the idea is to have central banks such as the Bank of Canada and the U.S. Federal Reserve target nominal GDP growth in setting monetary policy. The Bank of Canada already targets inflation. The idea is that by targeting nominal GDP, central banks can help national economies achieve better growth and generate more jobs.

Give Mr. Brison credit: He caught the wave just before it broke into the mainstream media. The Commons committee voted on Oct. 20 to hold a one-day session on NGDP targeting some time this month. Three days later, The Wall Street Journal reported that a growing number of economists and proponents are supporting the idea of having the Fed target nominal GDP “” or GDP without stripping out inflation.

A commentary in The Economist dated Oct. 25, “Understanding NGDP targeting,” generally favoured the idea, arguing that it would “likely perform better as a policy goal over inflation over the long run.” Then came Christine Romer, former chair of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors. In a column for The New York Times, Ms. Romer turned into a cheerleader for NGDP targeting. “Dear Ben,” said the headline, addressing Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, “It’s time for your Volcker moment.”

The Romer endorsement of NGDP targeting was unequivocal. Just as former Fed chairman Paul Volcker had wrung inflation out of the U.S. economy in the late 1970s, so Mr. Bernanke can now stuff some growth into the U.S. economy by the equally bold move of targeting nominal growth. If the Fed could target nominal growth of, say, 4.5%, the economy would settle into a new target path of 2.5% real growth (RGDP) and inflation of 2%.

Still more commentary is emerging by the day. It is clear Mr. Brison and/or his informers and advisors had ears to the ground on NGDP targeting. The question is, whom were they listening to? Mr. Brison cites “The Economist Intelligence Unit, [which] has put forth some ideas on this, and also the C.D. Howe Institute’s Monetary Policy Council, and people like Scott Sumner.” Scott Sumner certainly appears to be the most oft-cited source of theory on the use of NGDP targeting by central banks. He teaches economics at Bentley University in Massachusetts, and has been blogging on monetary policy for several years. His most influential paper on the subject, “The Case for NGDP Targeting: Lessons from the Great Recession,” was published earlier this year by the Adam Smith Institute and is available at adamsmith.org “” although the institute said it took no position on the subject.

Perhaps more influential in catapulting NGDP targeting into the mainstream was Goldman Sachs. On Oct. 15, one of Goldman’s economists, Jan Hatzius, concluded that U.S. growth and job creation could be given a shot in the arm if the Fed targeted nominal GDP. The idea, apparently, would allow the Bernanke Fed to unleash a new round of monetary easing. As Ms. Romer sees it, NGDP targeting would allow the Fed to take additional steps, including “further quantitative easing, more forceful promises about short-term interest rates, and perhaps moves to lower the exchange rate. Such actions wouldn’t just affect expectations; they would also be directly helpful. For example, a weaker dollar would stimulate exports.”

As for inflation, Ms. Romer joins the already-large crowd of economists who believe a little inflation is good for us. “A small increase in expected inflation could be helpful.” It would stimulate spending and encourage borrowing and buying of big-ticket items.

We will hear more of NGDP targeting in weeks and months to come. The debate also takes us all deep into the economic swamp, where creepy jargon and grotesque floating arguments and logical traps abound. One observation, though.

The idea of targeting nominal GDP has its origins, in part, in the work of some radical free-market economic theories. Prof. Sumner, for example, cites as inspiration economist George Selgin, at the University of Georgia, who wrote a book titled Less Than Zero: The Case for a Falling Price Level in a Growing Economy. The idea is that inflation could be close to zero over the long term, and that the only way to get to zero would be to allow inflation to rise and fall according to productivity changes in the economy. Putting an inflation target at, say, 3%, unnecessarily introduces inflation into the economy. Targeting nominal GDP would avoid injecting inflation into the economy. The best alternative, he said, was Free Banking and the elimination of central banks “” which is so very, very far from what Ms. Romer, Goldman Sachs or Mr. Brison are thinking about.”

http://opinion.financialpost.com/2011/10/31/terence-corcoran-%E2%80%94-ngdp-targeting-the-very-latest-econo-vogue/

1. November 2011 at 08:04

THIS IS HOW YOU SELL IT Scott!!!

“The idea of targeting nominal GDP has its origins, in part, in the work of some radical free-market economic theories. Prof. Sumner, for example, cites as inspiration economist George Selgin, at the University of Georgia, who wrote a book titled Less Than Zero: The Case for a Falling Price Level in a Growing Economy. The idea is that inflation could be close to zero over the long term, and that the only way to get to zero would be to allow inflation to rise and fall according to productivity changes in the economy. Putting an inflation target at, say, 3%, unnecessarily introduces inflation into the economy. Targeting nominal GDP would avoid injecting inflation into the economy. The best alternative, he said, was Free Banking and the elimination of central banks “” which is so very, very far from what Ms. Romer, Goldman Sachs or Mr. Brison are thinking about.”

It literally lets us say that the problem we have now is that the Fed allowed to much inflation in the past, and wages haven’t kept up.

We’ve had tremendous productivity gains, except for the public sector, for 20 years and during that time, the Fed should have been raising rates to have ZERO inflation anytime Growth ran over 3%.

People want to hear zero inflation, give them what they want.

1. November 2011 at 09:34

http://www.businessinsider.com/socgen-chart-fed-unemployment-2011-11

1. November 2011 at 10:07

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2011/11/case-against-case-nominal-gdp-target

As this originates from an author published by the “Economist”, it reminds me of the Peter Principle.

“There is no monetary policy the Fed could have pursued in the face of the collapse in housing prices in 2008 and ensuing financial panic that would have kept nominal or real GDP on track”

It’s like which came first, the chicken or the egg?

This is a gem:

“Mr Volcker abandoned it after just three years, later complaining about those “damned monetarists who kept criticizing us and expecting some control of the money supply that was beyond our TECHNICAL capacity”

Back then Volcker advised the congressmen to watch the non-borrowed reserves — “Watch what we do on our own initiative.” The Chairman further added — “Relatively large borrowing (by the banks from the Fed) exerts a lot of restraint.”

This was of course, economic nonsense. One dollar of borrowed reserves provides the same legal-economic base for the expansion of money as one dollar of non-borrowed reserves. The fact that advances had to be repaid in 15 days was immaterial. A new advance could be obtained, or the borrowing bank replaced by other borrowing banks. The importance of controlling borrowed reserves was indicated by the fact that at times nearly 10% of all legal reserves were borrowed. Also, discount window funds were provided not at a penalty but at a discount to other market rates.

1. November 2011 at 11:37

what is noteworthy on the graph is how wrong the forecasts have been – how many times NGDP is outside the forecast range. And: actual GDP appears more volatile than the forecast. It’s also interesting that, eyeballing the graph, the forecast error is persistent (by which i mean there seems to autocorrelation in the forecast error, that is, if the error is high in period t, the error is also high in periods t+1..etc, and vice versa).

I wonder to what degree this is caused by monetary policy itself (the Fed tends to be slow to act (“inertial” I believe is the technical term) and policy moves itself do not show up in the real economy for 9-12 months, according to lore i learned in grad school, so one can easily tell a story that the forecast continues to surprise upward or downward and the Fed is slow to act). And given the persistent forecast error, and lags between policy and the real economy, I wonder to what degree NGDP level targeting either exacerbates the instability or ameliorates it.

1. November 2011 at 11:48

God and the Economist loves me!

“So why doesn’t it? The Fed now finds itself in the odd position of being blasted from one side for doing too much and the other for doing too little. There is far more substance to the latter arguments than the former, but NGDP advocates base their arguments on a flawed premise: that with a different framework the Fed would have been less concerned about inflation and more about output, and would have thus eased more aggressively.

That was true for only for a narrow window: the summer of 2008 when oil prices spiked; at the time, the Fed, worried that high headline inflation could find its way into higher expected inflation, paused in its easing, although at least, unlike the ECB, it did not tighten. But for most of 2008, the Fed was easing. Scott Sumner and other NGDP advocates claim that had the Fed been targeting NGDP, it would have responded sooner and far more aggressively.”

Ya know, if you took the time to tell a story that covered 2004-2006 (where the Fed was raising rates), it lays the groundwork for a FAR MORE BELIEVABLE 2008.

Because if they had been more concerned when things were running hot, the housing boom would been CREDIBLY PISSED ON.

You can’t just start at 2008 and win.

MOREOVER, you get far more mileage talking about future action under a 4% (it’ll be less than 4.5% GS wants), and the positive effect that has on expectations.

Look Scott, YOU argue that Fed acts last – so they can neuter Fiscal.

But under this plan, the Fed no longer acts – they stick to the script.

This effectively puts the Government (mainly Democrats) on the hot seat.

We bang our heads on 4%, and the Fed raises rates, what happens?

1. Cost of government borrowing goes up.

2. Voters become ACUTELY aware that Federal Spending crowds out Private Growth from NGDP. We don’t want government growth adding to NGDP, it raises our rates, likewise, cutting government = lower rates for private parties.

UNDER a 4% level target, government shrinks. Period. The End.

And it is dumb that folks are talking about this stuff, without getting into the obvious positive feedback loop, of the Fed essentially dropping out.

1. November 2011 at 17:16

Ben, You said;

“Run, Scott “Money Swivelhips” Sumner!”

Hmmm, sounds like someone who works in a bordello.

Nunes, That may be worth a post.

JKH, How long until the minutes come out?

Morgan. You said;

“nunes, getting Sumner of sit on Greenspan’s lap is near impossible”

Hard to do if my hips keep swiveling.

Doug, That’s a weird comment. You decide what you think I should propose, then imagine that I actually propose what you wanted me to, and then assume the Fed decided to adopt my plan (which isn’t my plan it’s your plan) and then imagine that the Fed pouts because I keep complaining about them even though they adopted my plan, which is really your plan.

A lot of heroic assumptions there.

BTW, I started the trend line from mid-2008, when the economy had been in recession for 6 months, and unemployment was normal. The economy was in no way overheated at that time.

Anonymous, I agree with the first part of your post–those are good observations. But a couple quibbles:

I always find it interesting when people bring up these hypotheticals like 0%/5%. The assumption seems to be that it’s obvious NGDP would give you the wrong advice at those times. But 1/2 of commenters think the right advice would be more growth, and 1/2 think it would be less inflation. That tells me NGDP targeting is just about right.

The losses the Fed might earn are from tight money, not easy money. Tight money is why the base is so big right now. If money were easier and NGDP was 10% higher right now, they wouldn’t be facing any losses. I don’t agree that they’ll have to be bailed out. I don’t see why it matters if their capital goes negative. Their liabilities are cash, which has a floor of roughly a trillion. Their losses won’t be anywhere near that large. And don’t forget the implications of the EMH–their expected losses are near zero. So far they have made huge profits, which gives them a cushion.

Thanks JHK.

Morgan, But the Canadian thinks that’s a strike against the plan.

JimP, Thanks, That’s a great graph.

flow5, I agree with you about borrowed/nonborrowed reserves.

dwb, You should look outside that time period. It was way worse prior to 1983.

Morgan, So far government has increased their share of GDP under tight money.

1. November 2011 at 18:02

Minutes for FOMC meetings are out 3 weeks following the policy decision – so for this meeting, that should be Wednesday, Nov 23.

1. November 2011 at 18:20

Bernanke also holds a press conference tomorrow, so he’ll probably be asked about it there.

1. November 2011 at 18:22

@ JKH

Its a very old idea not a new idea.

1. November 2011 at 18:31

I don’t think NGDP targeting will get implemented though. 🙁

We are currently under a de-facto interest rate targeting regiem. Government debt is so huge that attempts to move away from this risk ballooning the payments on the debt the fed knows this.

I don’t see this fact changing any time soon.

According to Nick, interest rate targeting is the least good of the various targets (I agree), so I don’t see monetary situations improving.

1. November 2011 at 18:57

I agree that such hypotheticals actually strengthen the case for ngdp level targeting. All I was pointing out was that the Fed hates having to be tied down in such cases (even though that might be what we need). They will also use the “lender of last resort” function to weasel their way out of sticking to any target beyond short-term interest rates.

As far as posting losses go, yes it could only come from tightening monetary policy (hence why I mentioned exit). What my sources at the Fed’s markets group tell me is that they’re worried about what happens when they sell assets in a rising rate environment. The whole assumption seems to rest on the idea that once the economy gets going, it’s going to go gangbusters and they’ll have to quickly contract. I think that’s a misguided belief, but it’s definitely prevalent at the NY Fed. The profits they’ve earned serve as no cushion either since it all gets remitted back to Treasury; that’s why they’ve been trying to work some accounting tricks that allow them to place “future expected profits” on their current balance sheet if necessary. But even in that case, they still see posting a loss during the execution of exit strategy as a serious reputational risk.

4. November 2011 at 18:24

JKH, Thanks for the info.

Anonymous, Yes I understand the fear of capital losses on their assets. But:

1. It’s irrational because of the EMH.

2. It’s irrational because of the consolidated Federal government accounts are what matters.

3. It’s irrational to put a minor embarrassment ahead of the suffering of millions of unemployed.

4. The large balance sheet is caused by the Fed’s bizarre ERs policy, intentionally started in late 2008.

I’m not arguing with you, just exasperated that they could be this irrational about such an important issue.

And the last time a country came roaring out of a liquidity trap was? . . . Not Japan, not America in the 1930s, it was in the 1940s, in WWII. And even then rates didn’t rise. I don’t expect that our biggest problem will be a fast recovery.