The myth of Volcker’s 1979 assault on inflation

Commenter Russ Anderson pointed me toward a Fed publication that discusses the Volcker disinflation:

Twenty-five years ago, on October 6, 1979, the Federal Reserve adopted new policy procedures that led to skyrocketing interest rates and two back-to-back recessions but that also broke the back of inflation and ushered in the environment of low inflation and general economic stability the United States has enjoyed for nearly two decades.

This may be technically accurate, but it’s highly misleading. It creates the impression that Fed policy became contractionary in 1979 and that this gradually broke the back of inflation. But this simply isn’t so; monetary policy during 1979-81 was highly expansionary, as evidenced by rapid inflation and NGDP growth. The Fed only because serious about inflation in mid-1981, when it raised real interest rates sharply. This immediately broke the back of inflation. So much for long and variable lags.

The picture is complicated by two factors that seem to support the official narrative:

1. Monetary policy was briefly tightened in late 1979 and early 1980.

2. There was a brief recession in early 1980.

Both of those facts are true, but highly misleading. The tight money of late 1979 was not really all that tight, and it lasted very briefly. By late-1980 monetary policy was highly expansionary, indeed perhaps the most expansionary in my lifetime. Only in mid-1981 did the Fed seriously commit to tight money.

The recession of early 1980 was the shortest and mildest recession of the post-war era. And it occurred against a backdrop of deindustrialization in the rust belt, and punishingly high taxes (MTRs) on capital. The unemployment rate rose to a peak of 7.8%, but it was nearly 6% during the 1979 boom, evidence that President Carter’s bad supply-side policies were hurting the economy. In addition to high tax rates, we had energy price controls.

Although the recession officially began in January 1980, RGDP actually rose in the first quarter. As late as March 1980 few expected a recession, the economy seemed to be in an inflationary boom. Yes, the Fed raised the discount rate from 12% to 13% in mid-February, but about the same time the January CPI numbers came in at an 18% annual rate. Gold peaked at $850 in January. Thus in mid-March Carter put credit controls into effect to try to slow the economy and this pushed RGDP down at a 8.4% rate in the second quarter. Soon it became clear we were in recession, and the controls were quickly phased out. The recession was over by July, and housing and auto production recovered quickly. Nevertheless, during the ensuing recovery unemployment leveled off in the 7% to 7.5% range, despite ultra-easy money.

I’m probably the only person who’s ever called monetary policy during 1980-81 “ultra-easy.” This is right smack dab in the middle of the infamous Monetarist Experiment of 1979-82, the one that “broke the back of inflation.” But facts are stubborn things.

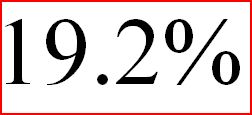

In mid-1980 the Fed panicked at rising unemployment, and cut interest rates back into the single digits, despite 13% CPI inflation during 1980. The result was predictable. NGDP started recovering briskly in the third quarter. But it was the next two quarters that were truly astounding; during 1980:4 and 1981:1, NGDP grew at an annual rate of:

.

.

.

.

.

That, my folks, is easy money. I can’t even recall a faster rate over six months, although I don’t doubt there were some. Think about how NGDP was “recovering” at just over 4% during 2010, and how the Fed huffed and puffed and pushed NGDP growth up to . . . 3.4% so far this year.

Yet this hyper-charged growth in AD did not significantly reduce unemployment. Believe it or not, 7% was probably the natural unemployment rate by 1981. It is not true that tight money cost Jimmy Carter the election. His poor supply-side policies combined with his neglect of inflation produced a high misery index on election day. That would have happened with or without Volcker.

In 1981 Reagan took over and supported Volcker’s fight against inflation. By mid-1981 the Fed got serious, and real interest rates began rising sharply. NGDP growth plunged into the low single digits. During the recovery Volcker did allow relatively rapid NGDP growth, but not enough to re-ignite inflation. Once RGDP growth leveled off, NGDP growth also slowed. The recovery was also helped by Reagan’s good supply-side policies, such as much lower MTRs, energy price decontrol, and a tough stance toward public sector unions. For the first time in my entire life the US began growing faster than most other industrialized countries.

So the 1979 assault on inflation is mostly myth. It was just a blip in the ongoing Great Inflation, which didn’t peak until early 1981, when NGDP growth peaked. Only in mid-1981 did the Fed get serious about inflation, and the results were almost instantaneous. CPI inflation during Sept 1980- Sept. 1981 was 11%, over the following 12 months it plunged to less than 5%. NGDP growth from 1981:3 to 1982:4 was at only a 3.4% annual rate. Why did almost everyone get it wrong? Because almost everyone believes in long and variable lags. And many people focus on nominal interest rates. And because it makes a good story.

PS. You might ask if monetary stimulus today might lead to disappointing results, just like in 1980-81. The answer is no, for reasons I’ll explain in the next post.

Tags: 1970s, 1980s, Volcker recovery

25. September 2011 at 11:15

Scott, the “market test” confirms your story. Around mid-81 US 10y bond yields start to ease off, the stock market actually drops (only to rebound in 1983) and the dollar strengthens (that however starts slightly earlier). So I would agree that the markets clearly indicate that US monetary policy remained overly loose until around mid-1981. The real test of monetary policy tightness should be observed in the market reaction to policy announcements.

In my view the credibility of the change in monetary policy was probably increased by (the wrong) perception that the new Reagan administration would reduce the budget deficit – so some pleasant monetarist arithmetrics probably also played a role.

25. September 2011 at 11:23

That’s probably ngNp.

“This immediately broke the back of inflation” No, Volcker never “tightened”. “So much for long and variable lags” No, 81’s lag was more accurate than any other.

25. September 2011 at 11:25

Ah, this takes me back to my (and Jim Glass’s) misspent (comparative) youth. We were having this discussion with a friend who produced a table for us here:

http://groups.google.com/group/sci.econ/msg/23a8ac40639623a7?&q=volcker+reagan+supply+group%3Asci.econ

Which he described as, ‘Volcker didn’t get serious about crushing inflation until after Reagan had come into office, as can be seen as the spread between the monthly prime rate and the cumulative 12-month log growth of the CPI, hence the real interest rate. These high rates caused the deepest recession since the 1930s, for which Reagan was widely blamed, and cost the Republican’s during the 1982 election.’

For example: 1979.12 15.3 12.44698419 2.853015805

In December 79 the Prime (banks’ best customers) rate was 15.3%, CPI inflation was 12.4% which gave us a real interest rate of 2.9%

By summer of the next year real rates were negative:

1980.08 11.12 12.12445486 -1.004454863

But things changed quickly:

1980.09 12.23 12.01696716 0.213032837

1980.10 13.79 11.89643707 1.89356293

1980.11 16.06 11.89519429 4.164805714

1980.12 20.35 11.64817993 8.70182007

1981.01 20.16 11.14955042 9.010449577

1981.02 19.43 10.7888962 8.641103799

1981.03 18.05 10.08560035 7.964399646

1981.04 17.15 9.654551041 7.495448959

1981.05 19.61 9.34167672 10.26832328

1981.06 20.03 9.255155737 10.77484426

1981.07 20.39 10.23292918 10.15707082

1981.08 20.5 10.27127827 10.22872173

1981.09 20.08 10.40485708 9.675142919

I take the above to be evidence that markets had caught on to what Volcker had done. He was worried that he’d ruined Carter’s re-election chances, so backed off from his monetarist experiment. The markets weren’t fooled.

25. September 2011 at 11:31

Sorry that didn’t format well.

1981.09 20.08 10.40485708 9.675142919 Should read:

1981.09 (year, month)

20.08 (Prime rate)

10.40485708 (CPI annual rate)

9.675142919 (difference, or real interest rate)

25. September 2011 at 12:28

I can by the way recommend Robert Hetzel’s discussion of US monetary policy in the early Volcker year’s in “The Monetary Policy of the Federal Reserve – A History” (2008). He describe the disinflationary policies as more gradual. Hetzel describe Volcker as being more anti-inflationist from the the outset of his mandate, but also acknowledge that it is really not before 1982 that a new anti-inflation regime with a nominal anchor is established.

By the way money supply data also confirm that monetary policy remained inflationary in 1979 and 1980. M1 growth did not really start to ease off before 1981.

25. September 2011 at 13:34

Fascinating review of a telling moment in US history.

Also, a reminder that things are not worse than ever today–we have lower marginal tax rates, a de-regged transportation sector, largely de-regged financial sector (remember Reg Q and passbook accounts?), a much-less unionized labor force, much more international trade (although lately we have keeping out labor—a structural impediment the GOP would prefer not to talk about). A case could be made that we have less structural impediments now than ever before in the post WWII-era , nationally speaking.

Of course, most structural impediments are probably at the state and local level, such as licensing lawyers or any other number of professions, regulating insurance, or any number of land-use regs and zones. (Try building a skyrise condo tower on the beach in Newport Beach, CA the GOP stronghold—first you have to get voter approval). Put a factory in Los Angeles? Hard to so.

Still, I think the Fed can easily crank it up and absolutely should. I will happily take some, even moderate inflation. in exchange for boom-times again.

25. September 2011 at 13:59

Can I point out that “long and variable lags” were part of Milton Friedman’s tenets of monetarism, which Bernanke quoted positively in a tribute speech to him just a few years ago?

25. September 2011 at 17:45

OH JESUS.

My god.

Some liberal econ egghead loser public employee way down the ladder at the Fed oversees some copywriter – and guess what?

In their shitbrain public employee mindset, the IMPORTANT thing is to tell the public that the Fed started this in 1979.

See 1979 means it WASN’T REAGAN. He gets now credit.

Now, the rest of us, say those who matter, are likely to vote, own stuff, and attend Tea Parties – WE KNOW THIS, so it is water off a ducks ass.

You however want to MISS the reason why and have a stupid shitty discussion about this like BEN himself blogged the Fed web site.

PLEASE, let’s just focus on HARD MONEY = 3% NGDP.

That’s our plan, let’s stick to it. STAY ON MESSAGE.

That is all.

25. September 2011 at 18:36

Lars, Thanks for that info.

Flow5, He tightened in mid-1981.

Patrick, That information is also supportive–thanks.

Ben , Good points.

JTapp, Yes, I think Friedman was wrong on that point.

Morgan, Glad you liked the post.

25. September 2011 at 19:11

Just imagine if we got 19.2% NGDP this year. Think it would make up for lost opportunity? Of course it doesn’t look like there is much chance of getting more than 3%. I really just wish the Fed would pick a happy medium, instead of this very unhappy one, and stick to it. This up and down like fireworks at a carnival, with QE, no QE, maybe we’ll just do the twist, to nothing at all is just incoherent psycho-babble. It looks more like the lady behind the counter at the DMV is setting policy, and I thought the FOMC/Fed Chair was supposed to be a cut above. Maybe that should be Bernanke’s next job.

25. September 2011 at 19:45

BTW, the econ-blog Carpe Diem has a nice post about inflation recently. We are on the cusp of deflation. possibly.

25. September 2011 at 20:02

Wow. Here I thought Oct 6, 1979 was one of those dates that everyone in economics knew, like Dec 7, 1941 and 9/11/2011 for normal people.

John B. Taylor wrote: “Anyone who was more than just a casual

observer of economic policymaking at the time realized that the measures announced on October 6 [1979] represented a major change in the conduct of monetary policy. […] The sustained monetary restraint called for by the operating procedures implied a protracted period of economic weakness. It called for a degree of fortitude by Chairman Volcker and his colleagues that had been highly atypical of central

banks in the late 1960s and 1970s. […] Chairman Volcker and his colleagues were resolute for the next couple years, and their efforts, along with subsequent ongoing vigilance to prevent the economy from overheating, paid tremendous

dividends for the United States.” http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/05/03/part2/Taylor.pdf

Alan Greenspan said: “A defining moment may shape the direction of an institution for decades to come. In the modern history of the Federal Reserve, the action it took on October 6, 1979, stands out as such a milestone and arguably as a turning point in our nation’s economic history. The policy change initiated under the leadership of Chairman Paul Volcker on that Saturday morning in Washington rescued our nation’s economy from a dangerous path of ever-escalating inflation and instability.” http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2004/200410073/default.htm

Bennett T. McCallum wrote: “Then, on October 6, 1979, the Fed, under Paul Volcker’s chairmanship, announced and put into effect a new attempt involving drastically revised operating procedures that had some prominent features in common with monetarist recommendations. In particular, the Fed would try to hit specified monthly targets for the growth rate of M1, with operating procedures that emphasized control over a narrow and controllable monetary aggregate, nonborrowed reserves (i.e., bank reserves minus borrowings from the Fed). The M1 targets were intended to bring inflation down from double-digit levels to unspecified but much lower values.” http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Monetarism.html

Anna J. Schwartz wrote: “In the three years (1979-82) under Volcker, disinflationary monetary policy, announced as being designed to contain growth in money aggregates, brought down the U.S. inflation rate from 10 percent to 4 percent.” http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/05/03/part2/MarchApril2005Part2.pdf

If this is a myth, people like Taylor, Greenspan, and Schwartz are spreading it.

26. September 2011 at 00:17

[…] […]

26. September 2011 at 01:30

So Volcker didn’t tighten until Reagan was firmly in office. Just a coincidence?

Doesn’t that rather prove the link between politics and the Fed?

And so we won’t see easing until (unless) the Republicans win in 2012?

26. September 2011 at 04:02

[…] Sumner gives an example of what he would consider easy money. […]

26. September 2011 at 04:26

Bonnie, Good analogy.

Ben, Thanks for the link.

Russ, You said;

“If this is a myth, people like Taylor, Greenspan, and Schwartz are spreading it.”

Yup, it’s a myth, for reasons I explain in this post.

Anna Schwartz’s statement would also be accurate as follows “In one year (1981-82)… ”

James, Unfortunately they do pay attention to politics.

26. September 2011 at 06:50

“Interest rates”, in and of themselves, don’t reflect easy & tight money. The degree of ease or restraint is determined by monetary flows (our means-of-payment money X’s its transactions rate of turnover) relative to rates-of-change in real output. Both lags for MVt are tightly corroborated.

Volcker simply let the economy smother itself. See: “New Measures Used to Gauge Money supply” WSJ 6/28/83 – Dr. Paul Spindt.

You mistake “tightening” with the aftermath of the “time bomb”: the widespread introduction of ATS, NOW, & MMMF accounts at the end of 1980 –which initially vastly accelerated the transactions velocity of money (i.e. these accounts became in effect interest-bearing checking accounts). This propelled nominal gross national product to 19.2% in the 1st qtr 1981, the FFR to 22%, & AAA Corporates to 15.49%. The explosion eventually fizzled out in a few months as account holders stopped spending their savings & money velocity fell sharply after mid-year.

28. September 2011 at 16:25

flow5, I think NGDP is the best way to define monetary policy, but any definition is arbitrary.

19. December 2011 at 10:20

[…] became Federal Reserve chairman and initiated the famous Volcker disinflation. Scott Sumner has argued that Volcker didn’t really tighten monetary policy before 1981. I agree with Scott that that is […]

18. May 2012 at 05:01

[…] an earlier post I pointed out that this myth was partly due to a misreading of the early Volcker years. Volcker […]

7. September 2012 at 07:46

[…] mid-1981. That’s shows his policy initially lacked credibility. I demolished that myth in this post. For those with limited time, […]

4. May 2013 at 19:30

[…] 1976 to 19% in 1981 was caused by easy money policies of Burns, Miller and Volcker, as I explain in this post. NGDP growth peaked at 19.2% in 1980:4 and […]

20. May 2013 at 18:10

[…] Second, and a point that was made a couple of years ago but is still highly relevant in the current economic/political climate, is that Keynesianism is a very difficult political sell. Part of the problem, however, is that the electorate has been conditioned to think certain things in the economy are good or bad. For instance, we all remember the inflationary concerns of the 1970s and early 1980s, with a jarring recession in 1981. Inflation bad. No. As Scott Sumner wrote: […]

29. September 2013 at 22:23

[…] Volckers saw the elephant for […]

25. March 2019 at 15:42

[…] course it's true that, in the early 1980s (not the late 1970s), Paul Volcker's Fed finally reigned-in the U.S. inflation rate. It's also true that the Dodd-Frank […]

26. March 2019 at 05:03

[…] course it’s true that, in the early 1980s (not the late 1970s), Paul Volcker’s Fed finally reigned-in the U.S. inflation rate. It’s also true that […]

26. March 2019 at 05:31

[…] course it’s true that, in the early 1980s (not the late 1970s), Paul Volcker’s Fed finally reigned-in the U.S. inflation rate. It’s also true that […]