The myth of the pro-German ECB

The ECB likes low inflation. So does Germany. That has led many people to wrongly assume that ECB policy is somehow pro-German.

In the long run the trend rate of inflation makes no difference; money is super-neutral. Greece and Italy are no better or worse off with a 2% trend rate of inflation, or an 8% trend rate (except for second order effects such as the distortions produced by the taxation of nominal income from capital.)

I recall attending a European economics conference about 6 or 7 years ago, and hearing German academics complain that ECB policy was appropriate for high-flyers like Spain and Ireland, but too tight for Germany. At that time Spain and Ireland had relatively high inflation (Balassa-Samuelson effect), and since the ECB was targeting average inflation, this meant slow-growers like Germany suffered from an excessively tight policy.

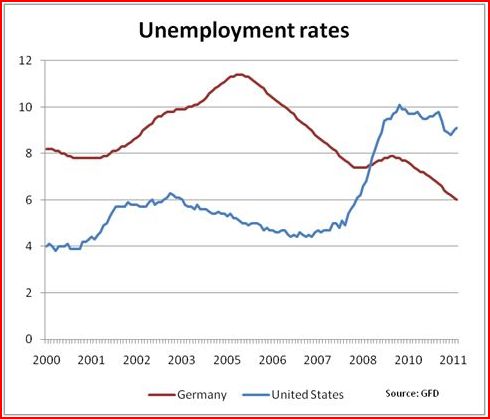

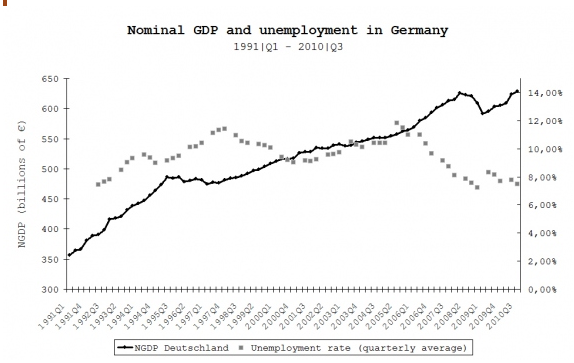

People forget that as recently as 2005 (when the world economy was doing well) Germany was viewed as the sick man of Europe. Unemployment had risen steadily to nearly 12%. It was viewed as a failed economic model. Too rigid, unable to adopt to the post-industrial 21st century. No one was talking about ECB policy favoring Germany, just the opposite.

How quickly things change, and how soon we forget. Germany is not doing better because it’s favored by the ECB; they were too tight for everyone in 2009. Rather it’s because labor market reforms put their wage costs in line with the ECBs tight money policy after 2005. It was a successful “internal devaluation.”

Here is graph showing the unemployment rate in Germany:

It may have been inevitable that the euro would crash and burn, but it might just as well been in 2005 when Germany was weak and Spain was strong. The problem is one-size-fits-all, not a pro-German slant.

This WSJ article discusses how Sarkozy is trying to emulate German labor market reforms:

The government’s employment proposal is designed to stop the job hemorrhage by providing companies with a buffer to keep their staff while still cutting payroll when business shrinks. During the 2009 recession, Germany limited job losses in part because of a popular subsidy program for short-hours work, known as Kurzarbeit. At the peak, in May 2009, as many as 1.5 million workers were in the program. German unions also have made wage concessions to preserve jobs.

. . .

The French government’s idea to increase work-time and pay flexibility is likely to meet much more resistance.

“All labor unions will say ‘No,’ because that would amount to making workers pay for the economic downturn,” said Mourad Rabhi, a leader at CGT, France’s second-largest union. “And in France there isn’t the same climate of mutual confidence between workers and companies, as in Germany.”

BTW, I agree with Tyler Cowen that Germany is well placed to do well in the future. Tyler mentions good governance, which in my view is partly related to cultural factors like civic virtue. But the relative performance of Spain and Germany around 2005 shows that these factors aren’t very useful for short term predictions. So don’t assume the current perception that Germany is the “strong man of Europe” will hold forever. History teaches us to expect the unexpected.

PS. Tyler Cowen is pretty cagey. He didn’t actually say he agreed with the quotation he provided; rather he said he hasn’t made up his mind. But the quotation he provided was his own words. I need to remember to do predictions that way in the future. 🙂

PPS. The always interesting Ambrose Evans-Pritchard has some cheerful predictions for 2012.