Should we target total wages or average hourly wages?

This post was inspired by a recent Nick Rowe post, which uses an AS/AD diagram to compare inflation and NGDP targeting under various sorts of shocks. I learned some things from reading the post, and George Selgin’s comments following the post. I recommend people take a look. But in the end I find sticky price models too confusing. Or maybe I just don’t have the energy to try to get over my confusion, because price stickiness doesn’t seem to me to be the key issue. For me, business cycles are all about employment fluctuations and wage stickiness.

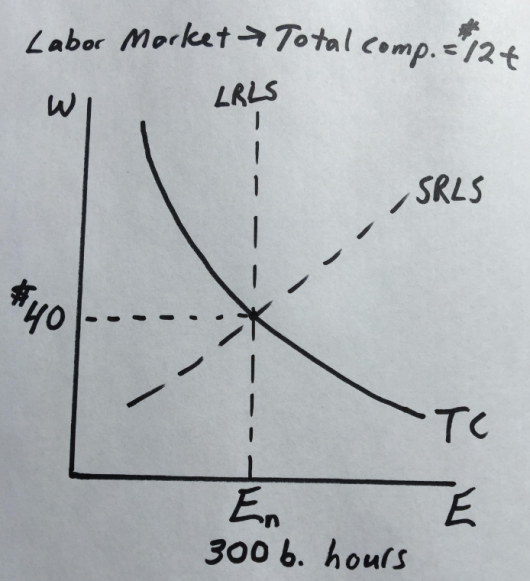

Let’s start with a graph where (for simplicity) we assume a vertical long run labor supply curve (LRLS), and an upward sloping short run labor supply curve (SRLS). Total compensation (TC) is a rectangular hyperbola, representing $12 trillion in labor compensation. I assume wages of $40 per hour (including benefits), and 300 billion total hours (2000 hours a year times 150 million workers.) These are ballpark numbers for the USA. The LRLS determines the natural rate of employment—which is optimal in the context of monetary policy decisions.

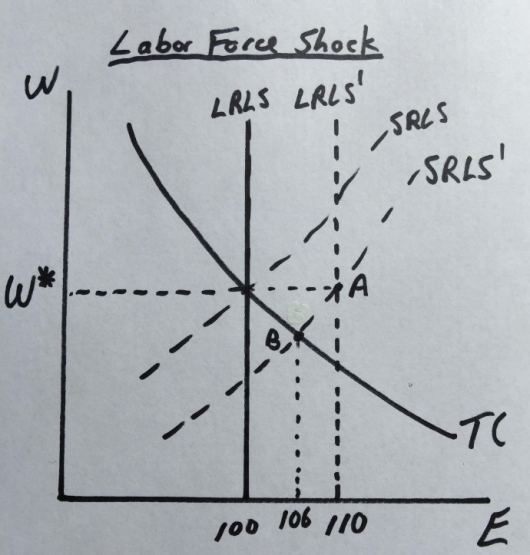

Now let’s consider two types of shocks. In the first case, there’s a sudden 10% boost in the labor force, perhaps due to a flood of immigrants:

Now let’s consider two types of shocks. In the first case, there’s a sudden 10% boost in the labor force, perhaps due to a flood of immigrants:

Notice that the optimal solution is a 10% rise in employment, with no change in nominal wages. That’s what happens with nominal wage targeting. Under total compensation targeting the employment level rises by only 6%, which is suboptimal. NGDP targeting would be the same. This example might help people to better understand George Selgin’s version of NGDP targeting, which adjusts for labor force changes. (Nothing changes if we assume a positive trend rate for wages that is fully expected.)

Notice that the optimal solution is a 10% rise in employment, with no change in nominal wages. That’s what happens with nominal wage targeting. Under total compensation targeting the employment level rises by only 6%, which is suboptimal. NGDP targeting would be the same. This example might help people to better understand George Selgin’s version of NGDP targeting, which adjusts for labor force changes. (Nothing changes if we assume a positive trend rate for wages that is fully expected.)

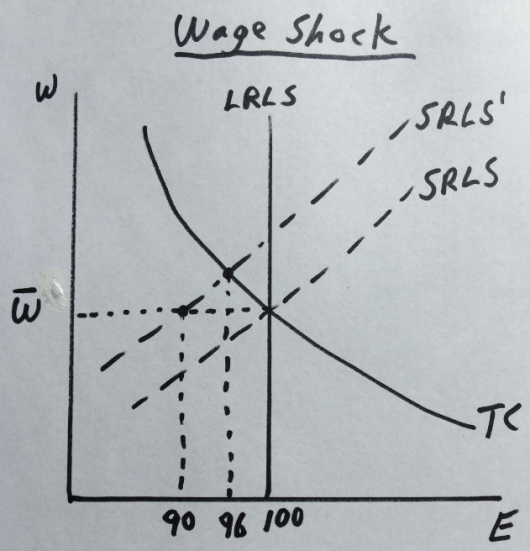

Now let’s consider a nominal wage shock. Say that workers get greedy and demand higher wages, because Bernie Sanders is elected President. But the LRLS doesn’t shift, which means the workers will eventually scale back their wage demands, at least in real terms:

This case is just the opposite. Now a monetary policy aimed at stabilizing total compensation gives you a better result. With nominal wage targeting, employment falls by 10%, relative to an unchanged LRLS curve. With total compensation targeting (and perhaps NGDP targeting as well) the fall in employment is smaller (only 4%).

This case is just the opposite. Now a monetary policy aimed at stabilizing total compensation gives you a better result. With nominal wage targeting, employment falls by 10%, relative to an unchanged LRLS curve. With total compensation targeting (and perhaps NGDP targeting as well) the fall in employment is smaller (only 4%).

In my view, the most pragmatic option is to try to target total compensation (or NGDP), adjusted for changes in the labor force, which is sort of in the spirit of George Selgin’s proposal. As I recall, he wanted a productivity norm that adjusted NGDP for both labor force and capital shock changes, but I don’t recall the exact details. Because I see the labor market as key, I’ve left out the capital stock issue, which seems secondary to me. But his basic intuition seems exactly right.

PS. It’s likely that this is nothing new, or maybe it’s wrong. It’s a framing that occurred to me after reading Nick’s post. I welcome any comments you might have.

PPS. I had the honor of writing a forward for the brand new addition to George’s Less Than Zero.

PPPS. Don’t be discouraged if all this theoretical analysis makes NGDP targeting seem “wrong”. It’s less far less wrong than anything else on offer from the major schools of thought in macroeconomics—close enough to optimal for the USA.

PPPPS. I didn’t look at productivity shocks, because they affect the optimal price level, not the optimal wage rate.

Tags:

25. November 2018 at 17:12

Why underplay capital stock? It seems to me that as jobs become more and more automated, capital will become more and more important relative to labor and wages.

When everyone has robots to do their work, capital stock might be the only thing that monetary policy and price level movements have short run effects on.

25. November 2018 at 18:13

I would guess that since robots are manufactured capital goods, their cost will fall over time. So labor would still be important as a scarce resource.

25. November 2018 at 18:39

Scott, I was reading your paper “A Market-Driven Nominal GDP Targeting Regime” and was confused when you said

using the net position in a NGDP futures market isn’t susceptible to the circularity problem.

If a Trader thought that NGDP would be above the 3.65% the contract was pegged at, then the Trader would buy the contract causing the fed to buy $1000 of securities on the open market. However, the trader will know that the Fed reduce the base by this amount in advance, so the fact the Trader took this position indicates he expect the change caused by his trade to be insufficient. Are you expecting the markets to be so liquid that now a different trader, upon seeing the contraction in the base, expects NGDP to be under 3.65%, and so short the contract and cause the Fed to take an offsetting position to the first trader; and so since the first trader can expect the change he causes in the money supply to be net offset he can in fact expect to profit?

Secondly, doesn’t this cause the fed to lose a lot of money paying bid-ask spread?

25. November 2018 at 18:48

Benoit, You said:

“Why underplay capital stock?”

Because I worry about employment of labor, not employment of machines. And I don’t believe that machines have sticky rental costs.

25. November 2018 at 19:51

Both are okay. They are including the same information of wage distribution.

Is there no unpaid overtime?

26. November 2018 at 02:54

Apropos sticky wages: I wonder if the much maligned ‘gig economy’ of Uber drivers etc already has a measurable impact on labour compensation flexibility?

26. November 2018 at 05:38

Scott, in the section of Less Than Zero titled “Which Productivity Norm?” I distinguish between a “labor productivity norm” and a “total factor” productivity norm, where the first allows for NGDP adjustments to accommodate changes in labor input only, and the second provides for NGDP adjustments to accommodate changes in both labor and capital input. I ultimately favored the total-factor alternative on pragmatic grounds, as it tends to involve less deflation.

Most of today’s proposals for NGDP targeting would allow considerably less deflation even than my TFP norm, for besides providing for trend NGDP sufficient to prevent labor (L) or capital (K) input growth from resulting in a lower price level, they provide for additional growth in trend NGDP sufficient to achieve a long-run expected inflation target of 2 percent, or something close to it. Implicitly at least, such proposals not only reflect an implicit worry about “sticky rental costs”: they go considerably beyond that in offsetting any sort of developments, however benign, that might otherwise cause output prices to decline.

26. November 2018 at 09:40

There is another option unmentioned here, for good reason, which is just targeting the the LRLC (or, in other words, keeping TC so it always intersects the LRLC at the SRLC). Of course that would be the ideal spot for keeping fluctuations in employment to purely real reasons and keeping money as a mere “veil,” although it would maximize variations in wages (it would move up to the y-axis of the Taylor Curve in terms of the tradeoff between variations in employment and wages, or output and prices). Such an option would fall prey to concerns about acquiring constant information about the natural level of unemployment (LRLC) relative to the SRLC, and concerns about lags, but in effect such complete real stability is the long-term goal of any NGDP targeting proposal. The only real question is the length of time during which the central bank should shift the TC or NGDP target (or maybe the distinction is only which time level of the LC or AS to target, since it is a continuum, from SRAS to MRAS to LRAS). Ideally, if we want to just trade wage for employment stability, the central bank would adjust the TC target at every microsecond of every day to ensure complete monetary “neutrality,” accommodating all shocks to the SRLC (say from price changes) and LRLC (from rains to flu). Instead, considering information gathering and lag concerns, we may just want to adjust TC (or NGDP) for shifts every quarter, or every five years, or whenever, but I think that this would just a matter of timing, not an essential distinction between different goals or models.

Constant TC or NGDP shifting, however, brings up another concern that Nick’s post also alludes to, that I don’t think gets enough attention, which is the game theory issues of price or wage setters facing the central bank (this is often discussed in relation to central banks and foreign exchange pegs, but I haven’t seen it relating to domestic issues). A problem with the central bank promising to accommodate short-term or medium term price pushes is that any monopolistic price setters (say, a powerful AFL-CIO), have an incentive to push the bank to accommodate their own wage or price demands, and perhaps get a jump on other, less monopolistic or slower firms, which could lead to an upwards wage or price spiral. Even if a central bank has an implicit assumption of accommodation of price increases to minimize output losses, and not a consistent level target, there may be a tendency for price-setting firms to push against a central bank when setting prices.

Maybe these are two entirely separate issues, and maybe the only real issue is whether to entirely ignore SRLC or SRAS curves, as is typical in NGDP targeting, and focus only on changes in the LRAS (effectively, the infinite time horizon aggregate supply curve, which is completely insensitive to any prices), in keeping the AD curve stable, but I do think an implicit debate about the timing of potential target shifts is behind some of these discussions.

26. November 2018 at 12:29

Judge Glock, you write that “complete real stability is the long-term goal of any NGDP targeting proposal.” But if “complete stability” means no fluctuations in real output, or as few as possible (and it is difficult to see what else it could mean) then this isn’t correct. In so far as “perfect info” real output itself fluctuates, than so should actual output.

I’m also not sure what the “C’s” in your acronyms refer to. In writing “the natural level of unemployment (LRLC),” you seem to imply that “LRLC” is the same thing as “LRLS.” But since you also use LRLS, that can’t be. So what is “C”?

26. November 2018 at 12:49

FToffer, You asked:

“Are you expecting the markets to be so liquid that now a different trader, upon seeing the contraction in the base, expects NGDP to be under 3.65%, and so short the contract and cause the Fed to take an offsetting position to the first trader; and so since the first trader can expect the change he causes in the money supply to be net offset he can in fact expect to profit?”

That’s how all liquid markets operate. There are a range of views, and people with differing views trade with each other.

On your second question, I don’t recall assuming any bid-ask spread in that example. In my alternative “Guardrails” proposal, the Fed wins on average.

Matthias, No, the gig economy is far too small to show up in the data.

George, Thanks for clarifying that.

Judge, The game theory problem you allude to is much worse if you try to target a real variable like employment. I don’t see it as a significant problem with an NGDP target. Even a powerful union needs to consider a fixed pie of NGDP when pushing for wage gains.

26. November 2018 at 15:51

>Because I worry about employment of labor, not employment of machines. And I don’t believe that machines have sticky rental costs.

No but machines have a sticky quantity. It typically takes time to harvest the raw materials, energy and build them.

If the aggregate needs machines later to maintain consumption, but money is made to hold real value better than stored machines, will anyone build machines for later? Won’t savers instead hold cash thinking they can buy machines with it later? Will they be able to buy them since they’re not being built?

26. November 2018 at 17:59

“Ohio becomes first state to accept bitcoin for business tax payments”

The above story may be important. Fiat money has value as governments accept it as payment and everybody must pay taxes.

I think this may be important in terms of what we ponder is the money supply, although at this point is perhaps too small to make much difference. But fun to watch.

27. November 2018 at 11:17

Benoit

Scott’s right not go too hung up on capital. The whole theory of capital is a mess as it is far too reliant on the machinery/hardware type of capital. Human capital is left out far too much, partly because it is so hard to measure. Economists prefer to focus on the easy, measurable, stuff. But if you are thinking of delayed consumption think of education, formal and informal, training on the job and off the job. It’s just as important today as ever, if not more so.

27. November 2018 at 13:57

>But if you are thinking of delayed consumption think of education, formal and informal, training on the job and off the job.

Sure, these things definitely count, but they also respond to monetary policy via student loans, employment etc. and they are also a sticky quantity. You can’t learn everything instantaneously on demand when you need it like in the matrix. You need to put some time learning and practicing ahead of the time you are going to need the knowledge.

27. November 2018 at 22:27

Thanks for taking the time to answer my question Scott.