Basil Halperin’s critique of NGDP targeting

Lots of people have tried to find flaws in NGDP targeting, but most of these posts are written by people who have not done their homework. Basil Halperin is an exception. Back in January 2015 he wrote a very long and thoughtful critique of NGDP targeting. A commenter recently reminded me that I had planned to address his arguments. Here’s Basil:

Remember that nominal GDP growth (in the limit) is equal to inflation plus real GDP growth. Consider a hypothetical economy where market monetarism has triumphed, and the Fed maintains a target path for NGDP growing annually at 5% (perhaps even with the help of a NGDP futures market). The economy has been humming along at 3% RGDP growth, which is the potential growth rate, and 2% inflation for (say) a decade or two. Everything is hunky dory.

But then – the potential growth rate of the economy drops to 2% due to structural (i.e., supply side) factors, and potential growth will be at this rate for the foreseeable future.

Perhaps there has been a large drop in the birth rate, shrinking the labor force. Perhaps a newly elected government has just pushed through a smorgasbord of measures that reduce the incentive to work and to invest in capital. Perhaps, most plausibly (and worrisomely!) of all, the rate of innovation has simply dropped significantly.

In this market monetarist fantasy world, the Fed maintains the 5% NGDP path. But maintaining 5% NGDP growth with potential real GDP growth at 2% means 3% steady state inflation! Not good. And we can imagine even more dramatic cases.

Actually it is good. Market monetarists believe that inflation doesn’t matter, and that NGDP growth is “the real thing”. Our textbooks are full of explanations of why higher and unstable inflation (or deflation) is a bad thing, but in almost every case the problem is more closely associated with high and unstable NGDP growth (or falling NGDP). In most cases it would be entirely appropriate if trend inflation rose 1% because trend growth fell by 1%. That’s because what you really want is stability in the labor market. If productivity growth slows then real wage growth must also slow. But nominal wages are sticky, so it’s easier to get the required adjustment via higher inflation (and steady nominal wage growth) as compared to slower nominal wage growth.

I said “most cases” because there is one exception to this argument. Suppose trend growth slows because labor force growth slows. In that case then in order to keep nominal wages growing at a steady rate, you’d want NGDP growth to slow at the same rate that labor force growth slows. As a practical matter it would be very easy to gradually adjust the NGDP growth target for changes in labor force growth. I’d have the Fed estimate the growth rate every few years, and nudge the NGDP target path up or down slightly in response to those changes. Yes, that introduces a tiny bit of discretion. But when you compare it to the actual fluctuations in NGDP growth, the problem would be trivial. I’d guess that every three years or so the expected growth rate of the labor force would be adjusted a few tenths of a percent. Even if the Fed got it wrong, the mistake would be far to small to create a business cycle.

Say a time machine transports Scott Sumner back to 1980 Tokyo: a chance to prevent Japan’s Lost Decade! Bank of Japan officials are quickly convinced to adopt an NGDP target of 9.5%, the rationale behind this specific number being that the average real growth in the 1960s and 70s was 7.5%, plus a 2% implicit inflation target.

Thirty years later, trend real GDP in Japan is around 0.0%, by Sumner’s (offhand) estimation and I don’t doubt it. Had the BOJ maintained the 9.5% NGDP target in this alternate timeline, Japan would be seeing something like 9.5% inflation today.

Counterfactuals are hard: of course much else would have changed had the BOJ been implementing NGDPLT for over 30 years, perhaps including the trend rate of growth. But to a first approximation, the inflation rate would certainly be approaching 10%.

[Basil then discusses similar scenarios for China and France.]

Basil’s mistake here is assuming that there is a 2% inflation target. As George Selgin showed in his book ‘Less than Zero”, deflation is appropriate when there is very fast productivity growth. Isn’t deflation contractionary? No, that’s reasoning from a price change. Deflation is contractionary if caused by falling NGDP. But if NGDP (or NGDP/person) is growing at an adequate rate, then deflation is an appropriate response to fast productivity growth. Indeed if you kept inflation at 2% when productivity growth was high, then the labor market could overheat. (See the U.S., 1999-2000).

Let’s suppose that the Japanese decide to target NGDP growth at 3% plus or minus changes in the working age population. In that case, the target might have been 5% in the booming 1960s, and 2% today (assuming labor force growth fell from 2% to minus 1%. Or they might have chosen 4% per person, in which case NGDP growth would have slowed from 6% to 3%. In the first scenario, Japan would have gone from minus 2.5% inflation to about 1%, whereas in the second scenario inflation would have risen from minus 1.5% to about 2%. Either of those outcomes would be perfectly fine.

As an aside, I recommend that countries pick an NGDP growth target higher enough so that their interest rates are not at the zero bound. But that’s not essential; it just saves on borrowing costs for the government.

Basil does correctly note that New Keynesian advocates of NGDP targeting don’t agree with market monetarists (or with George Selgin):

Indeed, Woodford writes in his Jackson Hole paper, “It is surely true – and not just in the special model of Eggertsson and Woodford – that if consensus could be reached about the path of potential output, it would be desirable in principle to adjust the target path for nominal GDP to account for variations over time in the growth of potential.” (p. 46-7) Miles Kimball notes the same argument: in the New Keynesian framework, an NGDP target rate should be adjusted for changes in potential.

Basil points out that this would require a structural model:

For the Fed to be able to change its NGDP target to match the changing structural growth rate of the economy, it needs a structural model that describes how the economy behaves. This is the practical issue facing NGDP targeting (level or rate). However, the quest for an accurate structural model of the macroeconomy is an impossible pipe dream: the economy is simply too complex. There is no reason to think that the Fed’s structural model could do a good job predicting technological progress. And under NGDP targeting, the Fed would be entirely dependent on that structural model.

Ironically, two of Scott Sumner’s big papers on futures market targeting are titled, “Velocity Futures Markets: Does the Fed Need a Structural Model?” with Aaron Jackson (their answer: no), and “Let a Thousand Models Bloom: The Advantages of Making the FOMC a Truly ‘Open Market’”.

In these, Sumner makes the case for tying monetary policy to a prediction market, and in this way having the Fed adopt the market consensus model of the economy as its model of the economy, instead of using an internal structural model. Since the price mechanism is, in general, extremely good at aggregating disperse information, this model would outperform anything internally developed by our friends at the Federal Reserve Board.

If the Fed had to rely on an internal structural model adjust the NGDP target to match structural shifts in potential growth, this elegance would be completely lost! But it’s more than just a loss in elegance: it’s a huge roadblock to effective monetary policymaking, since the accuracy of said model would be highly questionable.

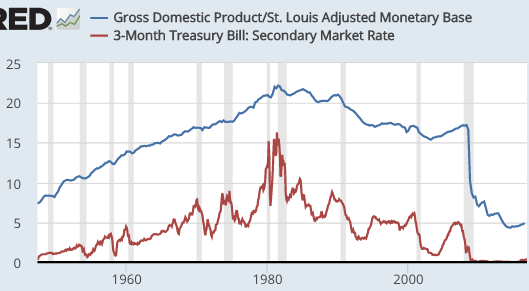

I’ve already indicated that I don’t think the NGDP target needs to be adjusted, or if it does only in response to working age population changes, which are pretty easy to forecast. But I’d go even further. I’d argue that the Woodford/Eggertsson/Kimball approach is quite feasible, and would work almost as well as my preferred system. The reason is simple; business cycles represent a far greater challenge than shifts in the trend rate of output. Because NGDP growth is what matters for cyclical stability, it doesn’t matter if inflation is somewhat unstable at cyclical frequencies. That’s a feature, not a bug. And longer-term changes in trend growth tend to be pretty gradual. In the US, trend growth was about 3% during the entire 20th century. Since 2000, trend growth has been gradually slowing, for two reasons:

1. The growth in the working age population is slowing.

2. Productivity growth is also slowing.

Experts now believe the new trend is 2%, or slightly lower. I think it’s more like 1.5%. But I fail to see how this would add lots of discretion to the system. Imagine if the Fed targets NGDP growth at 5% throughout the entire 20th century, using my 4% to 6% NGDP futures guardrails. No Great Depression, no Great Inflation, no Great Recession. Then we go into the 21st century, and the Fed gradually reduces the target to 4.5%, then to 4.0%. And let’s use the worst case, where the Fed is slow to recognize that trend growth has slowed. So you have slightly higher than desired inflation during that recognition lag. But also recall that only NKs like Woodfood, Eggertsson and Kimball think that’s a problem. Market monetarists and George Selgin think inflation should vary as growth rates vary.

Who’s opinion are you going to trust? (Don’t answer that.)

Seriously, even in the worst case, this system produces macro instability that is utterly trivial compared to what we’ve actually experienced. Or at least if we hit our targets it’s highly successful. And Basil is questioning the target, not the Fed’s ability to hit the target. You would have had 117 years with only one significant alteration in the target path. Yes, for almost any other country, the results would be far worse. But that’s why you don’t want to adjust the NGDP target for changes in trend RGDP growth.

Further, level targeting exacerbates this entire issue. . . . For instance, say the Fed had adopted a 5% NGDP level target in 2005, which it maintained successfully in 2006 and 2007. Then, say, a massive crisis hits in 2008, and the Fed misses its target for say three years running. By 2011, it looks like the structural growth rate of the economy has also slowed. Now, agents in the economy have to wonder: is the Fed going to try to return to its 5% NGDP path? Or is it going to shift down to a 4.5% path and not go back all the way? And will that new path have as a base year 2011? Or will it be 2008?

Under level targeting there is no base drift. So you try to come up to the previous trend line. In 2011 you set a new 4.5% line going forward, but until you change that trend line, the existing 5% trend line still holds. If you drop the growth path to 4.5% in 2011, then by 2013 the target for NGDP will be 1% less than people would have expected in 2008, and by 2015 it will be 2% less. In fact, NGDP was more like 10% less than people expected. So even if a gradually adjusting path is not ideal, it’s a compromise worth making to satisfy the NKs who are far more influential than I am, but have yet to read Less Than Zero. (George may not agree with the compromise, he’s less wimpy than I am.)

Before I close this out, let me anticipate four possible responses.

1. NGDP variability is more important than inflation variability

Nick Rowe makes this argument here and Sumner also does sort of here. Ultimately, I think this is a good point, because of the problem of incomplete financial markets described by Koenig (2013) and Sheedy (2014): debt is priced in fixed nominal terms, and thus ability to repay is dependent on nominal incomes.

Nevertheless, just because NGDP targeting has other good things going for it does not resolve the fact that if the potential growth rate changes, the long run inflation rate would be higher. This is welfare-reducing for all the standard reasons.

The “standard reasons” are wrong. The biggest cost of inflation, by far, is excess taxation of capital income. That’s better proxied by NGDP growth than inflation. Things like “menu costs” are essentially unrelated to inflation as measured by the government. The PCE doesn’t measure the average amount that the price of “stuff” changes; it measures the average amount by which the price of “quality-adjusted stuff” changes. Hedonics. If the government were serious about targeting inflation, they’d need to come up with an inflation measure that actually matches the supposed welfare costs of inflation in the textbooks. We don’t have that. We have nonsense like “rental equivalent”. The standard welfare costs also ignore the massive costs of nominal wage stickiness. And Basil mentions the incomplete financial markets problem. Please, can macroeconomists stop talking about inflation, and use NGDP growth as their nominal indicator? It would make life much simpler.

2. Target NGDP per capita instead!

You might argue that if the most significant reason that the structural growth rate could fluctuate is changing population growth, then the Fed should just target NGDP per capita. Indeed, Scott Sumner has often mentioned that he actually would prefer an NGDP per capita target. To be frank, I think this is an even worse idea! This would require the Fed to have a long term structural model of demographics, which is just a terrible prospect to imagine.

Actually, it’s pretty easy to predict changes in working age population, because we know how many 64 year olds will turn 65, and we know how many 17 year olds will turn 18. And immigration doesn’t vary much from year to year. The Fed doesn’t need long range forecasts; three years out would be plenty. As long as the market understands that the NGDP target path will be gradually adjusted for population growth, they can form their own forecasts when making decisions like buying 30-year bonds.

I want to support NGDPLT: it is probably superior to price level or inflation targeting anyway, because of the incomplete markets issue. But unless there is a solution to this critique that I am missing, I am not sure that NGDP targeting is a sustainable policy for the long term, let alone the end of monetary history.

I still think that NGDPLT, combined with guardrails is the end of macroeconomics as we know it. All that would be left is discussions of supply-side policies to boost long-term growth. The freshman econ sequence could be reduced to one semester. Or better yet a full year, with a more in depth discussion of micro.

PS. In this new Econlog post I make some forecasts.