The asset markets keep me from going insane

Over at Econlog I have a new post pointing out that negative IOR has had an unquestionably positive impact on asset prices, and yet much of the business press claims exactly the opposite. This confused thinking makes it more likely that central banks will adopt bad policies in the future.

A similar problem occurred in late 2007 and early 2008, when the media adopted a Keynesian approach to monetary analysis, instead of a monetarist approach.

From August 2007 to May 2008, the Fed repeatedly cut interest rates, from 5.25% to 2.0%. The media treated this as an expansionary monetary policy, even though it was clearly exactly the opposite. The monetary base did not change, and falling interest rates are actually contractionary when the money supply is stable. Indeed it’s a miracle the economy didn’t do even worse. NGDP growth slowed sharply, and I surprised there wasn’t an outright decline.

Here’s the monetarist approach:

NGDP = MB*(Base velocity), where V is positively related to nominal interest rates.

Thus if you cut interest rates without increasing the money supply, then V falls and policy becomes more contractionary. It’s monetary economics 101, but almost everyone seems to have forgotten this simple point. Market’s responded favorably to larger than expected rate cuts, because they implied a bigger than expected boost to the monetary base, on that day. But over time the base did not increase at all; the rate cuts were merely enough to keep it from falling. So do more!!

Because the media wrongly thought money was getting easier, they became (wrongly) pessimistic about the efficacy of monetary policy, which led to President Bush’s failed fiscal stimulus of May 2008. There is no economic model where Bush’s policy would be effective. Interest rates were above zero, so monetary offset was fully applicable. The Fed responded by putting rate cuts on hold, which drove the economy right off the cliff after June 2008. By September the tight money caused Lehman to fail, as its balance sheet was highly leveraged, and exposed to asset price declines triggered by falling NGDP expectations. Yet even Ben Bernanke inexplicably endorsed Bush’s tax rebates, even though there is no logical reason for him to have done so. If more stimulus was needed in May, then the stance of monetary policy should have been more expansionary. So do more!!

Bush’s policy was a lump sum tax rebate, which doesn’t even work on the supply-side. And unlike more government spending, there isn’t even a New Keynesian argument that fiscal stimulus might boost aggregate supply by making people work harder. It was really dumb policy, there’s nothing more to say.

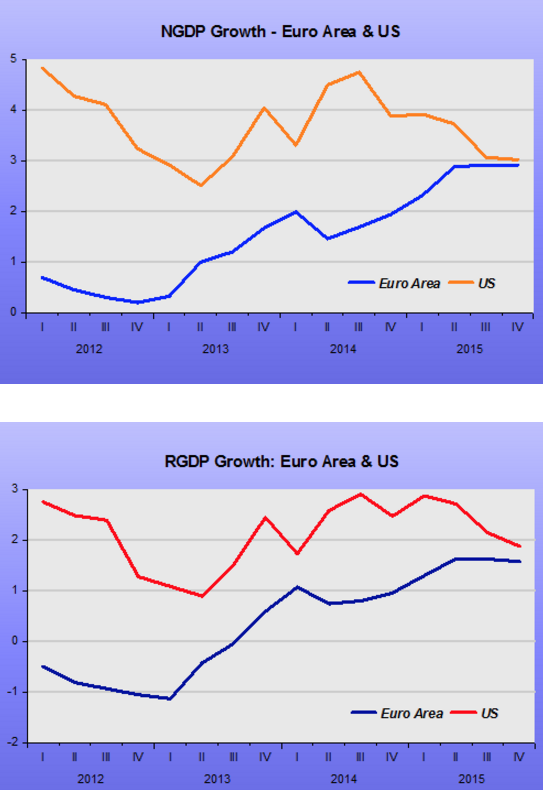

So because the media and many economists wrongly though money was loose, we ended up with really bad macro policy. The recent backing away from additional negative IOR is more of the same. Just as markets responded to unexpected rate cuts in late 2007 as if they were highly expansionary, markets responded to negative IOR in Europe and Japan as if it is expansionary. But over longer periods of time the markets were more negative, because investors rightly perceived that central banks would not do enough. So do more!! In 2007-08 investors were pessimistic because they thought the Fed wasn’t cutting rates fast enough. The Fed needed faster rate cuts to enable the monetary base to increase. So do more!! Similarly, in recent months, markets in places like Japan have become pessimistic because the BOJ is not cutting rates fast enough, or is suggesting it may give up. But the media thinks the market is pessimistic because the BOJ is doing negative IOR, even though asset markets respond positively to negative IOR.

In both cases, people wrongly assumed that the problem was that the measures that were taken were not effective. Instead of, “So do more!” it became perceived as, “So stop doing that, it’s not working.” They ignored the fact that markets clearly indicated it was working, but that much more needed to be done. Did I say, “So do more”?

Sometimes I think I’m going crazy—maybe everything I believe is wrong. After all, almost everything I read is diametrically opposed to what clearly seems to be happening, or to what our textbooks teach us about monetary policy. But then I look at the asset markets, and am reassured. I’m not really losing my mind. Monetary stimulus is effective, and it’s needed in Japan and Europe, and was needed in 2007-08 in America. No matter how many times the press tells us that the markets hate negative IOR, each new IOR news shock confirms once again that the markets prefer even more negative IOR in Europe and Japan. I don’t have my head in the sand, it’s the business press that does.