[I wrote this months ago, was dissatisfied, and decided not to post it. But now with all the reports about America’s poor, poor, pitiful 99%, it’d didn’t seem quite as silly.]

I’d like to make some observations about inequality. First as a person, then as an economist. These are based on 56 years of observing all kinds of people, in all sorts of different situations. The various inequalities are not meant to be equally important; indeed I’ve purposely added a few trivial ones for perspective. But they are all assumed to affect utility (although I don’t know that they all do.) Then I’ll return to this issue as an economist, and draw some conclusions.

1. Inequality of disability. Some people are blind, paralyzed, etc.

2. Inequality of talent. Some people are blessed with the ability of a Michael Jordon, or a Brad Pitt.

3. Inequality if liberty. I know one Chinese person who used to listen to Russian classical music very quietly, least the neighbors overheard. It was viewed as counter-revolutionary, and she could have gotten in a lot of trouble. Least we think America doesn’t have these problems, think of the many 100,000s of people in prison for using drugs.

4. Inequality of money (i.e. income/wealth/consumption.)

5. Inequality of personality. I know one part time instructor who always looks happy. He always whistles while he walks, and greets people with enthusiasm. He’s about 85. And I know lots of grouchy professors making 5 times more money.

6. Inequality of mental health–actually just a more extreme version of point 5–but a big driver of utility.

7. Inequality of access to health care. Often assumed to overlap with money inequality, but the Medicaid program suggests it’s more complex.

8. Inequality of power. My Marxist friends would say I have a blind spot for this one. I think I do.

9. Inequality of location. Were you born in sad Moldova, or happy Denmark?

10. Inequality of luck. Of course if there’s no free will, then it’s all luck.

11. Inequality of family situation. Are you living with an extremely difficult family member (an abusive spouse, an elderly person with Alzheimer’s, or a troubled teen.) This has a big effect on utility.

12. Inequality of disease. Do you have AIDS, or cancer?

13. Inequality of preferences. I am cursed with expensive taste. If I walk into a rug store, my eyes are immediately attracted to the most expensive oriental carpet. My daughter just bought a teal shag carpet from Target that she likes. Lucky her.

14. Inequality of pain. A hugely underrated factor in utility. And let’s not forget the poor hypochondriacs. There is no statement more stupid in the entire English language than “it’s all in your head.” Everything is all in your head, including pain. See the studies of phantom limbs. Pain is pain.

15. Inequality in social setting. Do you live in a neighborhood terrorized by crime. Again, only partially correlated with income.

16. Racial/ethnic/gender/sexual preference inequality

17. Inequality of nerdiness/awkwardness. A huge driver of utility for teenagers. (Would a poor but “cool” and popular teen trade places with a middle class nerdy teen?)

18. Inequality of job desirability

19. Inequality of appearance (beauty, obesity, etc.) Michel Houellebecq says this is the greatest source of inequality in rich countries

And I’m sure there are many more that I overlooked.

Now let’s look at the same list as drawn up by economists (including me, with my economist hat on.)

1. Inequality of money.

2. Inequality of access to health care

You might have noticed that the second list was a bit shorter. Some non-economists suggest that economists care too much about maximizing utility, and don’t care enough about income inequality. Of course exactly the opposite is true. We pay little attention to utility, and focus way too much on income inequality. BTW, this criticism could also apply to me, as I have done posts discussing ways of reducing consumption inequality.

I probably care less about income inequality than the average progressive. I think that’s partly because I’ve known lots of lower income people, and I’ve almost never found it to be the case that their income was the central problem in their lives. (Although it certainly is a problem–which is why I favor some income redistribution.) On the other hand, the sample I’ve known is very biased, and unrepresentative of all poor people. I’ve never known a migrant farm worker. Another reason I put less weight on income inequality is that money has always mattered less to me than to the average person, even when I had very little (age 18-26). Again, my view is slightly biased, as being poor and young is quite different from being poor and middle-aged.

But I do think I care as much about human suffering as the average progressive. Almost every day I wonder where the outrage is over 400,000 drug users in jail. By comparison, over the past 5 years I’ve read dozens of stories about the 400 terror suspects at Guantanamo. Yes, the issues are different in many respects, but I still see a lack of proportion. The drug war may be our greatest unnecessary loss of utility, showing up big not just in lost liberty, but also unnecessary pain from diseases, and more crime and violence.

As far as money problems, there is also a huge gap between America and the rest of the world. I recently heard a progressive criticize Obama. He started his comments by saying something like “If progressivism stands for anything, it stands for helping the middle class.” What?!?! Those sentiments are truly disgusting, repulsive. The focus should be on hunger in America. I hate to sound like an aging baby boomer, but at least in the 1960s the middle class was perceived by progressives as the enemy, unwilling to share their money and perks with poor black people. That’s not entirely accurate either, but at least it’s not morally repulsive.

Here’s a quotation from one of Peter Hessler’s excellent books on China. He’s conversing with a 33 year old professor in a God-forsaken college in western China during the year 1997:

But even amid these [traumatic modernizing] changes, Teacher Kong is not particularly worried . . . he is calm for the same reason that so many other Chinese are strangely placid in the midst of changes that seem overwhelming to outsider. Quite simply, he has seen far worse.

“When I was a boy we didn’t have enough to eat,” say Teacher Kong. “Especially in 1972 and 1973–those were very bad years. Part of it was that we lived in a remote place where the land wasn’t very good, but also there were some problems associated with the Cultural Revolution–problems with production and agricultural methods. It was a little better later in the 1970s, but still it wasn’t too good. We never ate meat; I was always hungry. Every day we ate rice gruel, and we only had a little bit of that. Rarely did we have salt. We ate weeds, wildflowers, pine needles–I’ve eaten all those things.

“My mother died when I was five, after she gave birth to my sister. Of course, we didn’t have milk or anything like that to help the baby, who died as well. I don’t remember that. But at the age of ten my father died, which I do remember. He got sick suddenly, a very bad cold, and in three days he was dead.

“After that things were even worse. My grandfather wasn’t strong enough to work, and I was too young to do much, so my uncle had to support all of us. At that time the Production Team in that village was very bad, and they weren’t of any help. Later, things improved and they were able to assist us, but for many years it was terrible.”

All of Kong Ming’s early life took place in the mountains outside Fengdu [Sichuan], a town that nowadays has about 30,000 residents. From his childhood home it took an hour by foot to reach the nearest road, which was three hours by rough bus ride from Fengdu, and as a result Kong Ming never saw the town until he was fourteen years old.

[As an aside, I won’t defend the Chinese view of Tibet, which is that they are bringing modernization to a backward people. But does the previous quotation help you understand why the Han people might have a slightly different perspective on the relative merits of modernization and traditional culture, as compared to the average American or European?]

Now let’s start down through Dante’s seven circles of Hell:

1. The US is much richer than Mexico. So much so that millions of Mexicans will risk the horrors of human trafficking into the US to get crummy jobs picking tomatoes all day in the hot sun.

2. China in 2011 is still considerably poorer than Mexico. The Chinese take much greater risks to get here.

3. China today is so much richer than China in 1997 that it’s like a different planet. The changes (even in rural areas) are massive.

4. The China of 1997 seemed like paradise compared to the China of the 1970s. Throughout Hessler’s book, people keep talking about how horrible things were during that decade and how prosperous they are now (1997 in Sichuan!)

5. The China of the 1970s was nowhere near as bad as during 1959-61, when 30 million starved to death.

It’s fine to worry about income inequality in the US. I also worry about this issue. But it’s important to keep in mind that there is much more to life than income inequality, and much more to the world than the US. In the grand scheme of things, tinkering with government programs to help the poor, pitiful, beleaguered American middle class isn’t likely to make much difference, at least from a utilitarian perspective. We need to broaden our outlook.

Unfortunately, Bryan Caplan’s open door policy is politically infeasible, but doing even 1/10th of what he asks for would be a huge boom to human welfare. Where is the conservative belief in “liberty?” (Insert Samuel Johnson quotation.)

And let’s not hear any more talk from progressives like Paul Krugman about trade barriers against Chinese workers.

PS. I just noticed this interesting data on how our poor compare to the world’s poor.

PPS. Peter Hessler’s MacArthur Award was very well-deserved.

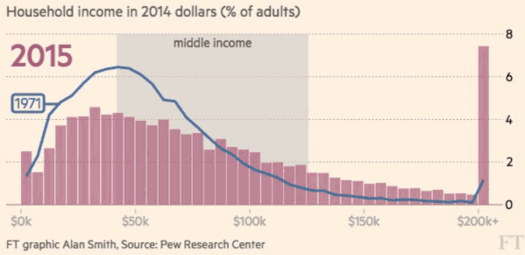

Do you see the problem? The main reason that the middle income group has shrunk is that more and more Americans have incomes above the (arbitrary) cut-off point, and fewer and fewer are either “middle income” or poor.

Do you see the problem? The main reason that the middle income group has shrunk is that more and more Americans have incomes above the (arbitrary) cut-off point, and fewer and fewer are either “middle income” or poor.