‘Regulation’ is not restraint, it’s intervention

I usually agree with just about everything David Beckworth posts, but I can’t quite buy the argument he makes here. David argues that low interest rates fed the 2001-06 housing boom. And not just low interest rates, but a Fed policy of low interest rates (which I see as a completely different argument.)

When the tech bubble burst, business investment plummeted. How should the economy react to that shock? In a classical world interest rates should fall sharply (regardless of whether a Fed even exists) and other types of output, such as residential investment, consumer goods, and exports, should pick up the slack. And that’s about what happened.

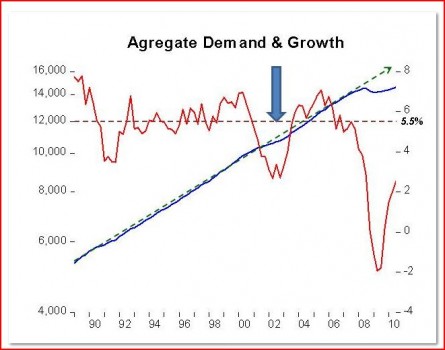

In my view interest rates are a very poor indicator of the stance of monetary policy. Both David and I favor roughly 5% NGDP growth targeting. As long as NGDP is growing at about 5%, monetary policy is on target, regardless of whether interest rates are 1% or 100%. And if you look at NGDP growth during the Great Moderation, it was in fact pretty close to 5%, on average.

During 2001 and 2002 NGDP growth fell a bit below 5%, and that’s why the Fed cut rates to 1%. In the subsequent expansion NGDP growth rose a bit over 5%, and the Fed reacted by raising rates sharply. I can see how someone would have thought money was a bit too easy during mid-2003 to 2006, when NGDP growth was above 5%, but I can’t see any catastrophic failures that could account for the spectacular sub-prime fiasco. We had even faster NGDP growth in the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s, none of which had a destructive housing bubble.

Update, 12/5/10: Marcus Nunes sent me the following:

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Having said all this, if I could go back in a time machine and run the Fed, I’d have raised rates faster in the 2003-04 period. But that’s not because I would have expected a much superior NGDP performance, but rather as a second best policy to address a catastrophic failure in our regulation of banking.

There is a widespread view that economists on the right favor “deregulation,” and economists on left favor increased regulation of banking. And the events of 2007-08 allegedly showed the left was right and the right was wrong. And I can understand why many people feel that way. Some right-wing economists did in fact offer poor policy advice–touting places like Iceland and Ireland as models of deregulation. But I think that’s the wrong way to think about regulation, I’d argue that places like Canada and Denmark are the true models of deregulation.

The problem is that people tend to think of the term ‘regulation’ as meaning something like ‘restraint’ whereas in the left/right debate over the role of government it means something closer to ‘intervention.’ Consider the advent of zero money down, no income verification mortgages. Does allowing banks to make those mortgages constitute “deregulation?” Not in my book. As I taxpayer I have always strenuously opposed all the federal interventions that make it easy to borrow money to buy a house–Fannie and Freddie, FDIC, FHA, etc.

Consider FDIC. Despite the fiction that banks pay the cost of FDIC insurance (about as likely as assuming gas stations pick up the cost of the federal excise tax on gasoline), FDIC insurance is a burden on us taxpayers. In a perfect world we’d have NGDP futures targeting and there’d be no need for FDIC. But in the world we live in deposit insurance is unavoidable intervention into the free market. I’d like to limit its reach as much as possible. I resent my tax money insuring banks that make sub-prime mortgage loans, or risky construction loans. I’d like to ban FDIC-insured banks from making housing loans with less than at least 20% down. I am not opposed to allowing sub-prime loans, just not with FDIC-insured money. If some unregulated financial intermediary wants to make such loans, that’s fine with me. I am no expert on this area, there might be alternative regulatory fixes that involve substantial private mortgage insurance, or some mix of insurance and equity. The point is that any and all acts that reduce the ability of banks to make FDIC-insured loans is “deregulation” in my book— it reduces the size and scope of the inefficient FDIC. For instance, I consider the Bush administration’s attempt to regulate the GSEs more tightly (opposed by my Congressman, Barney Frank) to represent deregulation.

There are actually two Republican parties in America. One wants to do real deregulation, to actually reduce the role of the government in the economy. The other Republican party (which I fear is the more powerful one) wants to do “deregulation,” to remove all constraints on business, banking, the medical industrial complex, energy, for-profit colleges, etc, so that they can systematically loot the taxpayers by taking advantage of the enormous moral hazard that has seeped into almost all aspects of our modern regulated economy.

The Dems are more likely to want to try to tame the beast, but then keep passing laws that make the economy even more riddled with moral hazard. Not much of a choice these days.

Tags: Deposit insurance, Housing, Regulation

4. December 2010 at 17:53

Seems to me that bubbles are created by multiple things.

For housing, not only did we have low interest rates, but a new law that exempted capital gains taxes on the sale of your personal residence.

We also had how many consecutive quarters of 3%-plus GDP?

We also had predatory lending and liar loans.

4. December 2010 at 19:15

A quick perusal of the Democratic ties to the GSEs and major financial institutions doesn’t suggest much desire to “tame the beast” on their part either.

4. December 2010 at 19:24

Muckdog wrote:

“For housing, not only did we have low interest rates, but a new law that exempted capital gains taxes on the sale of your personal residence.”

Not quite true. There was (and is) a capital gains exclusion. This exclusion was extended to second homes in 1997 for the first time in American personal income tax history. By my math (see the Shiller real home price index) that happens to mark the exact date the housing “bubble” started to inflate.

I don’t subscribe to the low interest rate theory at all. Core PCE inflation on an annual basis never exceeded 2.3% during the 2000s. But mostly it’s an all too convenient explanation for Austerians.

4. December 2010 at 19:26

Scott, since you repeat your points, I’ll repeat “mine”…

Maybe you’re wrong and, immaterial of arbitrary trend lines, NGDP shouldn’t grow but remain stable. Lets leave aside that a central bank executing some “policy” will always get it wrong as a top-down central planner.

If 5% NGDP growth as a policy produces excessive credit expansion in the face of productivity gains, that excess will go somewhere, especially areas of political allocation like housing, healthcare and education. I just see no reason why falling prices in one set of goods due to productivity gains should be offset by increased money supply which may push up prices in other goods. None.

My guess is that George is right, you are wrong, and 5% NGDP growth produces a credit-fueled boom and bust cycle. That cycle may be mitigated somewhat if the NGDP growth rate can be maintained through the bust, but I’m thinking it can’t. I’m thinking successive rounds of 5% NGDP-targed ease creates cumulative problems which eventually bust in such a way that it leaves precious few places for the printing press to paper over.

4. December 2010 at 19:28

Conservatives aiming at the wrong examples of conservative economic policy are not new. Wanniski fell in love with Côte d’Ivoire for its marvelously low rates in 1978.

Conflating the level of income redistribution and the pervasiveness of state regulation is common among some elements of the right and left. This is a regrettable state of affairs, really.

4. December 2010 at 19:34

Tremendous points about the nature of “regulation”, btw. Great stuff.

4. December 2010 at 19:38

I just realized another problem I have with the NGDP targeting idea. Correct me if I’m wrong, but NGDP calculation is a statistical approximation, right? How good is this data and how reliable is the source? It gets me thinking about the foundational data which my business targets: the Nielsen ratings. Even if we have a perfect system of targeting our show production to hit those numbers, the numbers are still a statistical construct approximating all viewership in this massive country based on a relatively tiny sample size. Seems problematic. Where am I going wrong?

4. December 2010 at 19:56

Scott, I know you don’t buy into the whole “interest rates were too low for too long” narrative, but are you at all concerned about the Austrian argument over “injection effects” of monetary policy?

NGDP growth of 5% sounds like a good goal, but the Fed has to buy something with the money it prints. Have you given any thought to what is the most neutral thing that the Fed could buy, or are you unconcerned about the effect on relative prices?

4. December 2010 at 20:28

Professor Sumner,

I still say the key unanswered question in financial regulation is explaining the 50 year absence of financial crises after the new deal and the next 30 years of busts after that. No one has ever, including you, whether the left or right, given a wholly consistent explanation for both. The left uses this to prove that deregulation is bad, the right simply says “its complicated.” Whoever can create a wholly consistent complete explanation deserved a Nobel. And I assume the solution would have to be provided by a monetarist of some sort.

This is similar for example to the unanswered questions as to why there was 25 years of massive growth everywhere after WWII and then a fall in productivity and growth after the 60s. No one has satisfactorily answered that one.

Hopefully your great depression book will explain why the great depression was so bad.

Best,

Joe

4. December 2010 at 20:28

You wrote, “Despite the fiction that banks pay the cost of FDIC insurance (about as likely as assuming gas stations pick up the cost of the federal excise tax on gasoline), FDIC insurance is a burden on us taxpayers.”

Do you mean that FDIC insurance is really paid by bank customers, or are you saying that the FDIC insurance payments from the banks are a trivial amount compared to the Treasury guarantee that backstops it all?

If the first, I disagree with your leap from “bank customers” to “taxpayers”, since not everyone saves in banks, and of the people who do the insurance costs aren’t passed on proportionally to the amount of other taxes we pay.

If the second, then the mention of the gas tax is misleading since there’s no way the gas tax is actually paid for by other taxes. I also remember seeing that the banks pay significantly more into the FDIC than the Treasury does, over the long run, so I’m skeptical that this claim is true.

4. December 2010 at 20:41

Joe wrote:

“I still say the key unanswered question in financial regulation is explaining the 50 year absence of financial crises after the new deal and the next 30 years of busts after that. No one has ever, including you, whether the left or right, given a wholly consistent explanation for both. The left uses this to prove that deregulation is bad, the right simply says “its complicated.” Whoever can create a wholly consistent complete explanation deserved a Nobel. And I assume the solution would have to be provided by a monetarist of some sort.”

Fascinating observation. My dissertation advisor is an unrepentant Republican. I’m hard line Democrat. But I chose him as an adviser for a simple reason. He probably understands macro better than anyone else in the department.

But we both agree on one point (and I think this relates to your point). Busting “bubbles” is bad policy. We did it in 1929 and we did it again in 2008.

4. December 2010 at 20:42

Muckdog, You must mean predatory borrowing, not predatory lending. The lenders were not repaid.

Mark I agree.

John, If 5% NGDP produced the housing bubble, then what would you expect 8% NGDP growth, or 10% NGDP growth to produce. The sort of growth we observed in some earlier expansions from the mid-1960s to 1990. But I don’t recall the Austrian model being able to explain those cycles. Is the theory one that is set up to explain one business cycle only? There are an infinite number of theories that can explain a single cycle.

The 1927-29 expansion had negative inflation, and still ended in the Great Depression. The Austrians say inflation should have been even more negative. I just don’t find those arguments credible.

Well at least we agree on regulation. Thanks.

David, Good points.

John, Actually, there is far more discretion, and possibility for mischief, in estimating price indices. The price increase in Dell computers is mostly guesswork (because of quality change), whereas the total revenue from the sales of Dell computer is a clearly defined number. There are problems in NGDP estimation, but much greater ones in price level estimation.

William, Injection effects are of trivial importance, because money doesn’t really go into markets, it goes through them. The Fed can buy bonds form banks, or they can buy them from individuals. If from individuals the person will usually put the money in the bank, so the effect is the same. In addition, monetary policy often affects the demand for money, not the supply. The Fed could sharply raise inflation without printing any more money. The monetary base is plenty big–if they had a lower IOR, and a higher NGDP target, that would speed up velocity.

4. December 2010 at 20:49

Joe, I have commented on that. Banking crises tend to occur during periods of disinflation. And the period from 1933 to 1980 was mostly one of ever higher inflation.

In addition, any regulatory regime will tend to deteriorate over time. Just because it worked once, doesn’t mean it will work when bankers figure out how to game the system.

In addition, the banking system was in terrible shape in 1980, before the “deregulation” occurred. I put deregulation in quotes, because in my view it was actually increased regulation, not deregulation, because it got the government much more involved in banking.

Jeffrey, The fact that not everyone has a bank account has nothing to do with whether it’s a tax. Not everyone smokes, but smokers pay the tax on cigarettes.

And in fact part of the cost is picked up by income taxpayers, when the FDIC fund goes broke and the government must bail it out.

4. December 2010 at 20:50

In something like the Diamond-Dybvig model, the point of deposit insurance is to force banking into its Pareto optimal equilibrium, as opposed to its Pareto sub-optimal equilibrium (bank run). Of course, if you have insurance, you need some combination of cost-sharing (e.g., captial requirements) and regulations on risk-taking to correct for moral hazard.

My question is, if NGDP grows at 5% a year by way of a monetary policy that runs on autopilot, does this make deposit insurance unnecessary because it prevents bank runs on its own, or are you working with some other kind of model of banking altogether?

4. December 2010 at 20:51

MikeDC, Good point.

4. December 2010 at 20:56

Ram, I’m not against deposit insurance, I just don’t think the government should provide it. All the large losses occur when NGDP is unstable. The private sector can insure losses of the scale that would occur with stable NGDP.

I partly agree with you. We don’t have stable NGDP, and hence FDIC is almost inevitable. But we’d do much better then if we sharply limited the sort of loans banks could make with insured funds.

4. December 2010 at 21:47

People who blame the Fed for excessive real estate appreciation remind me of alcoholics who blame the bartender for serving drinks.

I think loose underwriting standards were the cause of the bust, fed also by a MBS market in which Moody’s and S&P rated everything “AAA.” A Niagara of capital poured into global r/e markets.

There have been bubbles before the Fed, there will be bubbles in the future. People and investors are given to fads. So it goes.

It is worth pondering, this global supply of capital. It seems like there is too much capital. Not sure what that means. Low returns? Busts? A boom?

5. December 2010 at 01:47

traducción del español al inglés

I’ve always suspected that the main problem of the bubble is an excess of confidence & low risk premia, which are not due to just a state of euphoria of the people, but especially to certain laws and government interference.

When you see mortgage interest rates began to decline before the Fed lowered the FF to 1%, and that the bubble is accelerated after the Fed rates go up 5.25%, you have no choice but to think an excess of confidence that the all the risk is covered.

5. December 2010 at 03:14

Scott

Great to see you back in the real world. But you still have to decide that when real world messiness (“banks … can systematically loot the taxpayers by taking advantage of the enormous moral hazard that has seeped into almost all aspects of our modern regulated economy”) clashes with ivory tower monetary theory (“I have commented on that. Banking crises tend to occur during periods of disinflation.”) where do you stand?

The banksters gamed the “regulatory” system, as you say, and then I say they forced the Fed to bring in its put. Your blog is one of the foremost and public defences of the Fed put. Do you every think whether you have been captured and then arb’ed by the banksters?

Baseline Scenario has followed up Simon Johnson’s excellent blog yesterday with another from Prof Anat Admati.

http://baselinescenario.com/2010/12/04/what-jamie-dimon-won%e2%80%99t-tell-you-his-big-bank-would-be-dangerously-leveraged/

5. December 2010 at 03:17

Do you ever think whether … .

I work with banks, though am not a banker. I look at myself in the mirror every morning and ask myself have I been captured by the banks?

5. December 2010 at 03:21

Scott

I agree with you that DB does very nice and insightful posts but his obsession with the Fed being responsible for the house boom through low interest rates for too long is misplaced. Yesterday S Horwitz put up a paper at Mercatus on monetary disiquilibrium in which he also places the blame on the Fed:

http://mercatus.org/sites/default/files/publication/Great_Recession_Horwitz_Luther.pdf

I sent a picture to your e-mail which clearly shows that in 01-02 AD growth fell much below 5.5% and AD level dropped below the target path. To bring AD back to the level path AD growth was higher than trend in 03-04. In 05-07 AD was on target and growth was back at 5.5% but then Bernanke “lost it”!

In addition, home prices began the long climb in 1998, long before interest rates were lowered, following the asia crisis. This was how BWII worked: Resources in Asia were “transferred” to the tradable sector while in the US they moved to the nontradable (housing) sector… and everybody was “happy”. Unfortunately, politics got in the way and things ran out of control…

5. December 2010 at 03:27

Looking back at housing I always looked to the supply,demand, housing starts, inventory etc; real goods flow. Through that period, housing seemed to behave normally, except for the price. Money got screwed up, not housing.

And watching the Fed during the period they were typically late, but I see no other way for us to observe a central banker, except late by definition.

Something else in the economy changed at a faster rate than banking could adapt.

5. December 2010 at 03:47

The fed is always seriously behind the times. I expect that it will now keep its rates far too low for too long as well, or will QE later than it should.

Backward looking monetary policy makes the fed pro-cyclical instead of counter cyclical.

5. December 2010 at 05:06

Doc Merlin,

That’s a good point, actually. Until we get a future-looking, market-driven (or “market-controlled”) set of central banks, there will always be the danger of basing monetary policy on yesterday’s crisis.

It’s a potential problem even with monetary aggregate control. For example, when the UK Treasury abandoned targeting broad money in 1985 and only seriously monitored M0, which plays a trivial causal role in boom & bust cycles, since large transactions obviously aren’t conducted in notes & coin. As a result, any response to a movement in M0 was more likely to reflect what had happened rather than what would happen.

I still struggle to quite understand why inflation-targeting (whether implicit or explicit) took so long to be a disaster.

5. December 2010 at 05:55

I wish folk would stop talking about “the” housing bubble. There were housing bubbles in some places and not others. Since monetary policy is general, clearly there have to be specific features of where you had bubbles and where not. Bubbles involve discounting of downside risk. Supply constraints pushing up prices are a classic way of generating discounting of downside risk. As happened in California, Ireland, the UK … But not in Germany and Texas, which lacked either regulatory supply constraint or the land cartel of Ireland.

5. December 2010 at 06:46

Benjamin, Not so much too much capital, but rather too little AD.

Luis, I blame it more on bad regulation (moral hazard).

James, There is no contradiction in the two points you mention. One explains the underlying problem with the banking system, the other explains the timing of crises. Disinflation exposes the excessive risks that have been taken.

We probably agree on the flaws with the banking system, but I think give those flaws, the current recession should have been handled like 2002, with the Fed limiting the downside to NGDP.

Marcus, Thanks, I may add that picture as an update.

Matt, The Fed shouldn’t have to be targeting housing, and should pay no attention to whether it is screwed up. If it must pay attention, it’s a sign our regulatory system is totally screwed up.

Doc Merlin, I believe the Fed will raise rates too soon, then later regret it when we stumble again. It happened in Japan several times, and I see no reason why it won’t happen here.

Lorenzo, Yes, you are exactly right. I wish everyone would read your comment.

5. December 2010 at 08:02

Mark and Muckdog:

In 1997, when Congress, virtually out of the blue, passed the current tax law treatment of housing I firmly believed that they had created a potential bubble. That law, which made housing the investment with the best tax treatment of all investments any individual could own, would almost certainly drive housing into “bubble” status.

In 2002 or 2003, I wrote an article to Barron’s describing what was already happening to the housing market and where it would likely lead. Their economist denied housing had even accelerated in price yet and pooh-poohed the issue.

In 2005, I sent Tom Donlan at Barron’s the identical article for submission asking him how many financial articles he’d ever received that could still be published, unchanged, two years after the initial submission. He replied that it wasn’t many and asked me to make a few minor changes and re-submit it.

It was published in the Nov 14, 2005 Barron’s under the title “A Bubble-icious Tax Cut” by Rodney Everson. (I don’t know if Barron’s still has it online as I’ve dropped my subscription and Google doesn’t locate it for me now, but it was available a year ago.) If it’s still there, and you read it, you’ll see a 2005 forecast of exactly what happened later, including the change in sympathy today, and the extent of the likely drop. And that 2005 forecast was written in 2003, and formulated a few days after the change in the tax law in 1997.

Tax law drives investment decisions more than any other single factor and the 1997 tax law caused the housing bubble. Without it, all the predatory lending/FNMA foolishness/greed/corruption/etc. would never have happened. Does anyone think ethanol would be found at the pumps if the current tax treatment of ethanol had never been implemented, for example?

Oh, and the current tax treatment is the same as it was during the bubble. What’s that mean? That eventually it will all happen again someday. Housing purchased at the right price is far and away the best investment any individual can purchase, given existing tax treatment of investments. The key is getting it at the right price.

(Mark, in the short time since I found Scott’s blog I’ve noticed that you and I seem to think alike on several issues, including this one.)

5. December 2010 at 08:30

One hears that Bernanke is considering doing more public speaking. He is on 60 Minutes tonite.

If only someone knew enough to ask him about IOR or price level targeting.

5. December 2010 at 08:31

Or better – income targeting.

5. December 2010 at 08:52

My view is that at least Democrats give more to those in need, as imperfectly as they try to do it. My impression is they care at least somewhat about the less fortunate. My hope is that even “conservative” economists like you will eventually start to openly support Democrats, perhaps if things get so bad that you do so out of desperation for anything like a civil society.

I left the Democratic party for years, but recently returned. They are far away from where I want them to be, but things are so bad that I have to hold my nose and support them.

5. December 2010 at 09:15

Scott,

I don’t ever remember seeing you mention inflation swaps in particular and no results come up when I run a search for them in this blog. Does this market estimate current and future inflation well?

5. December 2010 at 09:16

Sorry, that second post was intended for your previous item on gold and inflation.

5. December 2010 at 09:25

Mike Sandifier,

I think that judging politicians on whether or not you think they care or not is a bad route to go down.

As for giving to the poor, that’s quite an ambigious issue-

http://taxprof.typepad.com/taxprof_blog/2005/11/generosity_inde.html

– I suppose you could say that Democrats, at least ideologically, are more “generous” with other people’s money.

Personally, I would favour the Democrats more than the Republicans if they either (a) became less economically “liberal” and/or (b) if they actually lived up to their reputation as social liberals and translated this reputation into serious policy. They’ve made some progress on (a) within my lifetime, but there’s still a long way to go before I would consider them as anything less than one of two horrific evils.

I’m just glad that I’m an observer of, not a participant in, elections that are like choosing between Sauron and Cthulhu.

5. December 2010 at 09:30

IIRC, Beckworth claims that there was a productivity surge in the early oughts. He’s cited some paper that shows a surging TFP during that time and has written that he thinks inflation should have been allowed. That seems like a great deal of faith to put into a residual statistic.

5. December 2010 at 09:52

That should have read, “he thinks deflation should have been allowed. That seems like a great deal of faith to put into a residual statistic.

5. December 2010 at 10:14

[…] David Beckworth (aqui), Steve Horwitz (aqui) e John Taylor (aqui) argumentam que sim. Scott Sumner (aqui) critica a conclusão de Beckworth. Como já mostrei (aqui), Peter Wallison, da Comissão de […]

5. December 2010 at 10:35

@OGT

The productivity issue was important in the second half of the 90´s. During those years inflation AND unemployment trended down. Many (including Krugman: http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/speed.html) thought that Greenspan was “behind the curve” and that inflation would soon “show its teeth”. Greenspan repeatedly in his presentations wondered wether productivity was rising, which would explain the simultaneous fall in unemployment and inflation. He kept his cool and the economy continued sailing…But towards the end of the decade people got “histrionic” and Greenspan relented and jacked up interest rates. An unwelcome effect of this “disturbance” was the fall in the S&P and Dow (Nasdaq was a different ball game).

5. December 2010 at 10:46

Rod,

With repect to the housing “bubble” everyone seems to talk about every theory under the son except the one theory that actually has a smoking gun next to it: The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. I’m glad I’m not the only one that feels that way.

5. December 2010 at 11:07

Scott that’s just what I meant, may not express myself clearly.

I think that what you call bad regulation is the source of that false sense of low risk. there are other factors that fostered it, as perverse incentives for short-term gain.

5. December 2010 at 11:22

@OGT-2

This Krugman 1997 HBR article is more serious than the one at Slate that I linked previously:

http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/howfast.html

5. December 2010 at 11:23

Beckworth appears to be a man of two different models. One is the monetarist “interest rates don’t matter” Sumnerian bent, and the other is the more ABCT model of “artificially low” interest rates– the Fed didn’t permit interest rates to rise along with the natural rate. The New Keynesian or neoclassical synthesis approach (which I would assume Beckworth was schooled in) allows one to critique the Fed in a way that sounds a lot like ABCT– focusing on interest rates.

How does one reconcile the models? Can you?

5. December 2010 at 12:41

Scott, I think this Woodford´s paper is very convincing, in the sense that the financial restrictions and intermediation also matter:

http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.24.4.21

(from marginalrevolution)

In any case, a strong demonstration that the low FF rate did not have any rol on the origin of the crisis,rather the reduction of risk premia -and intermediation margins- as it can be seen in fig 5.

Naturally, there is a “regulation” problem behind the fall of risk premia.

5. December 2010 at 13:37

I’ve read this post a couple of times and the comments. I am not an economist and I stopped reading this site because it seemed to believe in magic. Either I could just not understand it (likely), or it really made no sense. Well, lots of others think it makes sense, so it’s probably my ignorance.

But this post strikes me as pretty incoherent.

Here’s an example: “For instance, I consider the Bush administration’s attempt to regulate the GSEs more tightly (opposed by my Congressman, Barney Frank) to represent deregulation.” What does that mean? Regulation = deregulation?

Here’s another “address a catastrophic failure in our regulation of banking.” But you never say what that failure is/was.

And: “Does allowing banks to make those mortgages [zero money down, no income verification mortgages] constitute “deregulation?” Not in my book. As I taxpayer I have always strenuously opposed all the federal interventions that make it easy to borrow money to buy a house-Fannie and Freddie, FDIC, FHA, etc.” Well, we’re talking about NO interventions to prevent these liar loans, not regulations explicitly allowing them. I don’t think you can get from here to there with logic like that.

Or: ” In a perfect world we’d have NGDP futures targeting and there’d be no need for FDIC.” NGDP futures targeting guarantees there will be no corrupt and/or incompetent bank management?

“I’d like to ban FDIC-insured banks from making housing loans with less than at least 20% down.” I agree! Would that be an intervention or a restraint? Didn’t the world use to work like that?

Finally, the post starts with a discussion of low interest rates in the early 2000s and drifts to comments about Republican and Democratic policies. But I think you might be on to something when you say, “so that they can systematically loot the taxpayers.”

I’m sure it’s just my ignorance, but I couldn’t help myself. I probably need some regulation or at least an intervention.

5. December 2010 at 13:40

Christina slaps the Fed and Congress around a bit.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/05/business/05view.html?ref=business

Begin quote

In a paper I wrote many years ago, I found that such macroeconomic uncertainty helped start the Great Depression. The stock market crash in October 1929 didn’t destroy a particularly large amount of wealth or make people highly pessimistic. Rather, it made companies and consumers very unsure about future income, and so led them to stop spending as they waited for more information.

How do we resolve uncertainty about future growth? The Federal Reserve, Congress and the president need to reaffirm that they will do whatever it takes to restore the economy to full health. They could take a lesson from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who declared in his 1933 inaugural address that he would treat the task of putting people back to work “as we would treat the emergency of a war.”

They should follow up with powerful fiscal and monetary actions to create jobs “” coupled with a concrete plan for tackling our long-run budget problems. We are at a critical moment. With many in Congress opposed to further jobs measures and tax increases of any kind, the chances of prolonged gridlock are high.

BUT such policy paralysis would be a disaster. It would make uncertainty more acute by leaving us to the unpredictable forces of natural recovery and with no prospect of resolving our unsustainable deficits. Aggressive action to restore growth and face up to our long-run challenges is the only true and lasting solution.

end quote

I wonder if Ben understands that she is saying that what he has done thus far is just not good enough.

5. December 2010 at 13:43

Thus far one has the impression that Obama and Ben treat the task of putting people back to work as an emergency on about the same scale as choosing what to have for lunch.

5. December 2010 at 13:57

JimP, you don’t know how right you are. For example:

“I served seven years as the chair of the Princeton economics department where I had responsibility for major policy decisions, such as whether to serve bagels or doughnuts at the department coffee hour.”

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/11/14/AR2005111401544.html

Not much has changed.

5. December 2010 at 14:26

Not much of Roosevelt on display there. Sadly.

5. December 2010 at 15:43

JimP,

I’m such an old school Democrat I have this hanging in my living room:

http://images.imagestate.com/Watermark/1152506.jpg

Right next to my cross and images of my family (as well as my diplomas). He’s staring at me as I write.

5. December 2010 at 16:13

We are buying bonds in order to get interest rates down – and we will not allow inflation to go over 2% and we can raise interest rates in 15 minutes.

The man is a danger to the country.

5. December 2010 at 17:08

Ron, I agree the tax treatment of housing is a mistake, and I agree it tends to raise housing prices, but I don’t quite see how it causes a bubble. It seems to me it should permanently raise housing prices.

JimP, Let me know if he says anything interesting on 60 minutes.

Mike, Well put.

I don’t know much about inflation swaps. Are those CPI futures? If so, I’d expect them to provide slightly higher inflation estimates than TIPS spreads. I’d expect TIPS spreads to underestimate inflation expectations, and CPI futures to overestimate inflation expectations. This is because TIPS yields are slightly higher due to the fact that TIPS are less liquid, and I’d expect the sort of person who hedges in the CPI futures market to be someone worried about high inflation. If longs dominate CPI futures, then the equilibrium price might be a bit above expected inflation. This all might be wrong, but it’s my best guess.

W. Peden, That’s a good point. There are a half dozen areas where I think Obama has libertarian leanings (war on terror, war on drugs, free trade with Cuba, etc) and I don’t see where he has pursued a single one of those goals. Conversely, Bush was supposed to believe in lower Federal spending.

OGT I’m puzzled by the productivity argument you mention. If one favors a NGDP target, then productivity should not be a factor in Fed policy. I do think David has an argument that NGDP growth was a bit above average during the housing boom, but not very much. At worst, Fed policy was a minor factor.

Marcus, That’s a good point. I don’t have a big problem with his raising rates in the late 1990s, but I think they should have been cut more aggressively after the bubble burst. Still, in retrospect when you look at the NGDP growth path that David Beckworth always uses, the 2001 recession is hard to see. In your growth rate diagram it is more noticeable. At the time I thought the Fed made a fairly big error, but after this crisis their error in 2000-01 seems fairly small.

Luis, That’s right.

JTapp, A good question to ask in his comment section. He knows more about recent mainstream macro modeling than I do, I recall for instance that he is less skeptical of VAR models than I am. So I imagine he has more elements of mainstream economics in his general approach, but am not certain on this particular issue.

lxm, You criticized this:

“Here’s an example: “For instance, I consider the Bush administration’s attempt to regulate the GSEs more tightly (opposed by my Congressman, Barney Frank) to represent deregulation.” What does that mean? Regulation = deregulation?”

Yes, that was pretty incoherent. I should have put the term “regulate” in quotation marks. I meant that what is generally viewed as “regulations, i.e restraint on behavior, is in a sense “deregulation,” i.e reducing government intervention in the economy. The GSEs represent massive government intrusion into the housing market. If you limit their behavior, you reduce the role of government in the housing market.

I think I did describe our failure of banking regulation. We had the government guarantee bank liabilities, and then let them take great risks with government guaranteed funds.

NGDP targeting does not prevent banks from behaving badly, it means if they do behave badly it doesn’t cause a recession, hence no need for FDIC.

You asked:

“”I’d like to ban FDIC-insured banks from making housing loans with less than at least 20% down.” I agree! Would that be an intervention or a restraint? Didn’t the world use to work like that?”

Yes, exactly my point. It would be a restraint. But it would also mean less government intervention in the economy, as the government would be guaranteeing a much smaller number of loans. I want to get the government out of the financial system, one way is to reduce the amount of loans that use government-backed money. You do that with restraints. Restraints mean less government intervention in the economy.

JimP, Thanks for the link. A year ago I said Obama should talk to Christy. It’s pretty clear now that he didn’t. No way he leaves those Fed seats empty for 15 months if Romer had his ear. Thanks Larry.

5. December 2010 at 18:23

Scott

I paraphrased what he said above. It was not very good. The inflation hawks really have their hooks into him. Not the slightest smallest hint of price level targeting – and of course no questions about that or about IOR from the TV guy.

5. December 2010 at 20:31

Scot,

Yes, ordinarily a tax advantage should result in a step-up in the value of an asset, rather than a bubble. However, once prices started adjusting (as they should have,) it became broadly expected that they would continue to rise and that one was a fool not to buy early and big, and to hold instead of selling. I believe the tax change provided the impetus for the bubble, especially since it went generally unacknowledged as a cause for rising prices initially, and that human greed (in many forms) took over from there.

In other words, Scott, I don’t think the housing bubble would have occurred had Congress not made housing such a tax-favored investment. (The old treatment was favorable already, but nowhere near as favorable as the 1997 change.) And since they have kept the law unchanged since 1997, it will probably happen again, about a generation later, as I mentioned in the Barron’s article.

Rod

5. December 2010 at 23:18

Did you hear Steve Williamson said the zero lower bound does not bind… because we can use fiscal policy! Why does he call himself any sort of “monetarist”?

5. December 2010 at 23:41

Scott you said:

“I think I did describe our failure of banking regulation. We had the government guarantee bank liabilities, and then let them take great risks with government guaranteed funds.

NGDP targeting does not prevent banks from behaving badly, it means if they do behave badly it doesn’t cause a recession, hence no need for FDIC.”

You say you can’t see the contradiction but then you repeat it very clearly. Govt guarantees bank liabilities, they behave badly. If banks do behvave badly NGDP targetting means no recession.

Why can’t you see it? Banks are INCENTIVISED to behave badly knowing they and the economy will be bailed by (admittedly, hesitant, incompetent, in your eyes) effective NGDP targetting. And this cycle will get worse each time. LTCM bubble and burst, the tech bubble and burst, the housing bubble and burst. You are just way too naive. Go and work inside a Wall St bank for a while, or with some of the more foolish fixed income investors. All operate on the basis of the Fed (or should we call it the Sumner) put. The banksters love you.

I do recall your even more specific response a few weeks ago when you said you would have even bailed Lehman’s, the essence of TBTF. It’s never ever an easy time when banksters have pushed the system to the brink, but then they are all great poker players, and almost always have fixed the game anyway. Almost all Lehman staff are back in the game on high salaries and bonuses.

6. December 2010 at 06:18

@Scott:

“Ron, I agree the tax treatment of housing is a mistake, and I agree it tends to raise housing prices, but I don’t quite see how it causes a bubble. It seems to me it should permanently raise housing prices.”

I am in complete agreement on this point here, Scott. Housing volatility has been shown to be a result of market restrictions in new housing. The cities that avoided the bubble were ones where supply could change to meet demand fairly quickly without large price changes. This has also been argued to be true macro-economically by Levon Barseghyan and Riccardo DiCecio.

“The authors investigate the relationship between the quality of institutions and output volatility. Using instrumental variable regressions, they address whether higher entry barriers and lower property rights protection lead to higher volatility. They find that a 1-standard-deviation increase in entry costs increases the standard deviation of output growth by roughly 40 percent of its average value in the sample. In contrast, property rights protection has no statistically significant effect on volatility.”

http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/10/05/Barseghyan.pdf

6. December 2010 at 06:22

Oh, I should add, this has been roughly my thesis since the beginning of the blog, that barriers to entry cause pro-cyclical changes in the macroeconomy.

(I also think fed policy has the same effect, if it sets interests too low it causes /in effect/ a barrier to entry for new savings and too high a barrier to entry for production of capital)

6. December 2010 at 19:04

JimP, Yes, that’s depressing.

Rod, I generally assume rationality, but it’s a moot point as we both agree the policy is bad. In retrospect it would have resulted in a smaller bubble.

TGGP, His blog never seemed very monetarist to me. He seems somewhat right of center, but that’s not the same as monetarism.

James, You are again confusing micro issues (banking regulation) and macro issues, (optimal NGDP target path.) They are separate issues. You don’t create depressions just to punish banksters.

Doc Merlin, Yes, you and Lorenzo have been right about the problem of zoning restrictions. That is why Texas had no bubble.

8. December 2010 at 03:59

Scott

You punish banksters (and their owners and some of their funders) to prevent them in future from overleveraging, creating bubbles, that then burst and cause recessions. Always leaving the banksters and the markets to expect a bail-out via a Fed/Sumner Put will not lead to the behavioural changes that economy needs. Banksters exploit (place bets on) your fear of a depression, creating a vicious circle of leverage, boom, busst, bail, leverage, boom, bust, bail … . There is an intimate link between micro behaviour of banksters and the expectations that your macromancy (as someone once called it) will ride to their rescue. Calling it a “silly” argument is pathetic. Address it!

9. December 2010 at 07:21

James, The premise of your argument is wrong. Recessions aren’t caused by overlending, they are caused by tight money. In a perfect world where NGDP is growing steadily, some debts won’t be repaid and some banks will fail, which is appropriate. But those failures won’t cause recessions.

This is my blog, you need to address my arguments.