It’s better to “not target” NGDP (level targeting) than to “not target” inflation

There is a new post at the St. Louis Fed that is purportedly about NGDP targeting, but actually is about . . . well I’m not sure what it is about. At times Daniel Thornton seems to be discussing instrument rules (where to set the fed funds target), and at other times he seems to be discussing targeting rules (NGDP vs. inflation targeting.) Consider the opening paragraph:

Old debates about the use of rules versus discretion for conducting monetary policy and the efficacy of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) targeting have recently returned to the forefront of monetary policy discussions. The economics profession has largely sided with rules over discretion, while the debate about nominal GDP targeting continues. However, despite the support among economists for policy rules, transcripts of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings suggest that the Federal Reserve has never used a policy rule, and there is no evidence that any other central bank has either. On the surface, a nominal GDP-targeting rule would seem easier to agree on and, hence, more likely to be adopted. However, this essay discusses reasons policymakers have not used policy rules and are unlikely to target nominal GDP.

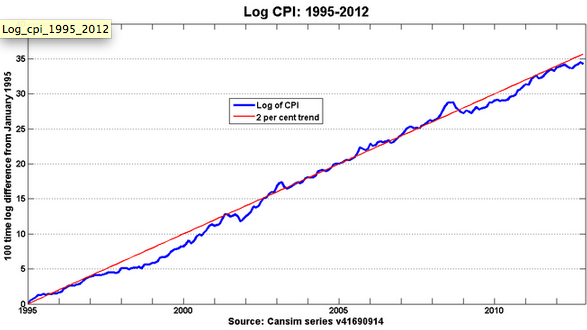

Now obviously lots of central banks have adopted various sorts of rules, just not the sort that Thornton seems to consider rules. The Fed adopted a rule of stabilizing gold prices at $20.67/oz, from 1914 to 1933. Under Bretton Woods many central banks fixed their currencies to the dollar. More recently, Canada adopted an inflation target. Nick Rowe shows how well it worked:

The Bank of Canada does not have a crystal ball. But over the last few years its lack of a crystal ball didn’t seem to make much difference. Even with the benefit of hindsight, we can say that the Bank of Canada made almost no mistakes in doing what it needed to do to keep inflation on target.

The Bank of Canada kept inflation on target, almost exactly as it was supposed to.

And we know this wasn’t just luck, as Canadian inflation was much higher and more volatile during the earlier decades. Oddly, some economists insist it was luck, claiming that OMOs don’t do anything, as fiscal policy drives the price level.

Now Thornton obviously knows that central banks have successfully targeted gold prices, forex prices, and inflation. So presumably he means something different by “policy rules”. Indeed he goes on to discuss the Taylor rule, which is a very different sort of rule. It’s an “instrument rule,” a recipe for how policymakers should set the fed funds target, in order to hit their broader macro goals (inflation or NGDP.) And he’s right that no central bank has rigidly followed an instrument rule for interest rates, at least none that I know of.

But NGDPLT is not like the Taylor rule; it’s like inflation targeting. It’s a targeting rule. It sets the macro objective, not the interest rate path that is mostly likely to hit that objective. So why does he title his article as follows:

Is Nominal GDP Targeting a Rule Policymakers Could Accept?

In the final paragraph Thornton seems to realize that something was missing from his analysis, and tries to quickly patch things up:

The fact that monetary policy has been discretionary does not mean that policy rules and other basic economic relationships are useless. Indeed, they can be quite useful as guides to monetary policy decisionmaking. For example, it is useful to know whether the policy rate is consistent with the rate implied by the historical relationship given by a Taylor rule or, as I have suggested elsewhere, the Fisher equation.2 In the final analysis, however, policymakers will use discretion and not rules to conduct monetary policy.

Hence the title of my post. So rules such as inflation targeting can indeed be “quite useful as guides to monetary policy decision-making,” even if they don’t slavishly following a Taylor-style instrument rule in hitting the target. My claim is that we should replace inflation targeting as a “quite useful as guides to monetary policy decision-making” regime with NGDPLT as a “quite useful as guides to monetary policy decision-making” regime. Do what the Canadians did, except for NGDPLT.

PS. Thornton also makes the following odd claim:

So what prevents the Fed and other central banks from adopting nominal GDP targeting? Again, there are a number of reasons, but an important and sufficient reason is that nominal GDP targeting requires policymakers to be indifferent about the composition of nominal GDP growth between inflation and the growth of real output, and, in general, they are not. For example, let’s assume the target is 5 percent and nominal GDP is growing at 6 percent. Would policymakers react the same if the composition was 1 percent inflation and 5 percent real growth, or 5 percent inflation and 1 percent real growth? It seems unlikely.

That makes no sense to me, it would be like saying that a 2% inflation target means that policymakers should be indifferent between a situation with 1% service price inflation and 3% goods price inflation, versus a situation of 3% service price inflation and 1% goods price inflation. Yes, I suppose it would imply that, but why should we care? If Thornton has studied the NGDP targeting literature then he certainly knows why NGDPLT proponents say we should be indifferent between those two scenarios. But he never explains why that argument is wrong.

BTW, when commenters bring up the 1%/5% hypothetical, I am amused that they all insist the Fed would behave very differently in the two cases. But half insist the Fed would be tighter with the high inflation situation, and the other half vehemently insist just the opposite, that the Fed cares more about growth. So it’s far from obvious why these two situations would call for different Fed policy responses.

PPS. His article would have been greatly improved if he had kept in mind two concepts; changes in instrument rules necessitated by more information about the relationship between policy instruments and the macro targets (inflation, NGDP, etc), and changes in targeting rules necessitated by new information on the relationship between the macro aggregates and social welfare. This Bennett McCallum paper is a good introduction.

HT: RyGuy Sanchez, Keshav Srinivasan

Tags:

19. October 2013 at 07:20

Krugman goes after Prof. Sumner:

“ZLB Denial”

“Since late 2007 the monetary base has risen more than 300 percent, while GDP and consumer prices have risen less than 20 percent. And no, the disconnect is not all due to the 0.25 percent interest rate the Fed pays on reserves.

You can argue that the Fed could have done more “” it could have expanded its balance sheet even further, and/or moved into riskier assets, and/or done more to change expectations. But I don’t see how you can deny that making monetary policy effective has been far harder since we hit the ZLB than it was before, and that this retroactively casts great doubt on Friedman’s claims that the Fed could easily have prevented the Great Depression.”

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/19/zlb-denial/?_r=0

19. October 2013 at 07:32

“If Thornton has studied the NGDP targeting literature then he certainly knows why NGDPLT proponents say we should be indifferent between those two scenarios.”

If possible, could you explain further? Or rather kindly point me towards your own explanations within previous blog posts and/or said NGDP targeting literature? Thanks.

19. October 2013 at 07:50

Scott,

Off topic.

Here is Krugman’s latest:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/19/do-currency-regimes-matter/

“…First, nominal wage stickiness “” the key argument for the virtues of floating exchange rates “” is an overwhelmingly demonstrated fact. Rose doesn’t offer reasons why this doesn’t matter; he just offers a reduced-form relationship between currency regimes and economic performance, and fails to find a significant effect. Is this because there really is no effect, or because his tests lack power?

Second, there is the very striking empirical observation that debt levels matter much less for countries with their own currency than for those without. Here’s one view of the relationship between debt levels and borrowing costs (data from Greenlaw et al):

[Graph]

And here’s another view of the same data, with euro members identified:

[Graph]

It sure looks as if debt matters only for those on the euro, doesn’t it? For what it’s worth, here’s a regression of interest rates on debt that uses a dummy for euro membership, and allows an interaction between that dummy and debt:

[Table]

Indeed: debt only seems to matter for euro nations…”

So, four days ago Krugman posted a scatterplot in which the two thirds of the nations are eurozone members, igoring the effects of currency regime, in order to make the argument that fiscal policy matters at the zero lower bound. Today he posts another scatterplot in which a majority of the nations are eurozone members, but this time he literally highlights the currency regime, and tests for the effects of interaction, in order to make the argument that debt matters much less for countries with their own currency.

The fact that his previous post was the intellectual equivalent of Greenlaw et al, purporting to show a relationship through the use of a scatterplot consisting mostly of eurozone members without any recognition at all that the relationship is entirely driven by the fact that these nations do not have an independent monetary policy, seems to have completely escaped his notice.

19. October 2013 at 08:11

I was similarly puzzled by this note. In particular, requiring indifference at any given point in time does not require indifference in general so long as there are changing demand conditions. The author argues against rules based policy for particularly this reason so I don’t see how he can have it both ways.

http://ashokarao.com/2013/10/18/getting-nominal-income-targeting-wrong/

19. October 2013 at 08:38

Mark it’s true that all these countries are in the eruo yet as they have such different results among the countries this would have to be attributed to fiscal policy. That the ECB has been so tight is not an argument against fiscal austerity.

19. October 2013 at 08:41

I mean it’s not an argument for fiscal austerity.

19. October 2013 at 09:15

Dinero offset;

http://santiagotimes.cl/us-debt-crisis-slower-world-growth-lead-to-unexpected-rate-cut/

———quote———–

The debt crisis in Washington may have been resolved temporarily, but continued concerns over the economic stability of the world’s largest economy has played a role in the Chilean Central Bank’s surprise decision to lower the country’s key interest rate for the first time in 21 months.

In a report released Thursday, the Central Bank justified the decision which it hopes will stimulate cooling economic growth.

“In the global economy, a weaker medium-term scenario has consolidated, characterized by slower world growth, lower terms of trade for Chile, less favorable financial conditions and the maturing of the global cycle of mining investments,” the report says.

….The Central Bank’s report also cited events in Washington as a factor in its decision to change the country’s monetary policy, noting that the fiscal agreement reached the U.S. Congress was “temporary,” and that “further financial tensions cannot be ruled out.”

….With economic growth forecasted at 4 to 4.5 percent, Chile’s economy is still among the fastest growing in Latin America, while regional powerhouses Mexico and Brazil are expected to grow at rates of 1.7 percent and 2.4 percent respectively in the next year.

———-endquote———–

19. October 2013 at 10:02

Mike Sax,

“Mark it’s true that all these countries are in the eruo yet as they have such different results among the countries this would have to be attributed to fiscal policy. That the ECB has been so tight is not an argument [for] fiscal austerity.”

Mike, obviousy if government spends more money in Fargo, North Dakota, GDP goes up…..in Fargo, North Dakota.

The whole point of Krugman’s original “Five on the Floor” scatterplot was to show fiscal policy has macroeconomic effects because presumably the nations in his sample are in a liquidity trap, which renders monetary policy ineffective. But if the sample is dominated by nations that are all subject to the same monetary policy, how does that show monetary policy is ineffective?

Obviously monetary policy is not going to have a different effect in Fargo than in Bismarck.

Furthermore, how on earth can this be construed as an argument *for* fiscal austerity?

19. October 2013 at 10:14

Travis, It depends what you mean by “harder.” If you mean “can’t use the familiar interest rate instrument any longer,” then I agree. But it’s easy to use other tools.

Wawawa, In the right margin I link to my National Affairs piece, and you can also google out my Mercatus piece (the one defending NGDP targeting, not the one defending NGDP futures contracts.)

Mark, Excellent point.

Ashok, Yes, that’s puzzling.

19. October 2013 at 11:29

“how on earth can this be construed as an argument *for* fiscal austerity?”

Mark I don’t get why this is so hard. The whole point of the monetary offset argument is to show that fiscal austerity is no problem as long as the CB offsets it. Ergo, the implication is that we should have more austerity as this won’t be harmful it will just lead to more monetary offset which is preferrable anway as that’s less public debt-according to the premise.

I don’t know why it’s so hard to get you guys to just admit that you’re making an argument for fiscal austerity. Now you don’t say this expicitly. However, implicitly it’s obvious. At the least you’re saying there’s not a thing in the world wrong with fiscal austerity-do you deny this?

However, while you quarrel with me for connecting the dots why don’t you quarrel with Morgan Warstler when he does the same thing only he praises it?

“It’s not just that MP can do the lift during bad fiscal (more of the PK view of QE), but that since we are going to use MP, we ought to free our minds and let go of Bad Fiscal when we look at a given policy and say “well at least it creates jobs” etc.”

“As such, once we commit ourselves to MP, it’s morally wrong to have BOTH Minimum Wage and a Safety Net.”

19. October 2013 at 12:04

“””that nominal GDP targeting requires policymakers to be indifferent about the composition of nominal GDP growth between inflation and the growth of real output”””

Policy makers should care deeply about the composition of NGDP growth.

But not the monetary authority. It’s not their business to care and they do not have the tools to change the mix that much either. The fiscal authority and the regulatory authority-bureaucracy have the power to change that.

(Conversely, fiscal policy should not care about demand. It’s not their business and not the right tool.)

This is the Fed resisting being turned into an utility.

19. October 2013 at 12:24

Thornton expressed himself carelessly when he wrote that “nominal GDP targeting requires policymakers to be indifferent about the composition of nominal GDP growth between inflation and the growth of real output . . . .” Suppose I adopted the rule of always paying the amount of income tax that the government imposed on me. Obviously that does not imply that I am indifferent about the amount: it is perfectly consistent to follow the rule of paying what amount is imposed, while hoping that it will be smaller rather than larger. And so the Fed may hope that NGDP growth is more real growth and less inflation, while still adhering to NGDP level targeting.

19. October 2013 at 14:18

Mike Sax,

“Mark I don’t get why this is so hard. The whole point of the monetary offset argument is to show that fiscal austerity is no problem as long as the CB offsets it.”

No Mike, that is most certainly not the point. The point is that the liquidity trap is a myth.

“Ergo, the implication is that we should have more austerity as this won’t be harmful it will just lead to more monetary offset which is preferrable anway as that’s less public debt-according to the premise.”

Or alternatively, one implication is that monetary is never impotent. And if so, there’s no reason why NGDP needs to be 15% below trend.

If NGDP were at trend then tax revenues would be much higher and its likely that social insurance expeditures would be much lower, meaning the deficit would be much smaller or even nonexistent. Furthermore the ratio of government debt to GDP would also be much lower.

Were all that true, I suspect that the motivation for fiscal austerity would completely vanish.

“I don’t know why it’s so hard to get you guys to just admit that you’re making an argument for fiscal austerity.”

The reason why it’s so hard is that it’s simply not true. I have never once advocated fiscal austerity. You are obviously becoming unmoored fom reality.

“Now you don’t say this expicitly. However, implicitly it’s obvious. At the least you’re saying there’s not a thing in the world wrong with fiscal austerity-do you deny this?”

Mike, I hate to see some of my favorite government programs cut. But that’s entirely different from saying those cuts will have negative effects with respect to macroeconomic stabilization policy.

“However, while you quarrel with me for connecting the dots why don’t you quarrel with Morgan Warstler when he does the same thing only he praises it?”

Morgan and I agree on almost nothing outside of monetary policy. This proves nothing to me except that you are losing your sanity.

19. October 2013 at 14:33

“Were all that true, I suspect that the motivation for fiscal austerity would completely vanish.”

So fiscal austerity is cylical? Pretty perverse if true. It’s not a question of my losing my sanity it’s you not comprehending what you read. I didn’t say that you and Morgan agree or don’t disagree just that he has made the same argument I am and yet you or no one else takes issue when he says it. He celebrates the idea that NGDPLT will keep the world safe for fiscal austerity-which is defintely his take on it as well. Did you read his quote? Yet when I point out the same thing it seems to perplex you.

I dont think I’m being unmoored from reality. Perhaps this is what all cult members think of the one person in the room who does’t drink the Coolaid. Maybe I seem that way to you as you’ve drunk so much Coolaid.

19. October 2013 at 14:59

Mike Sax,

“So fiscal austerity is cylical? Pretty perverse if true.”

Isn’t it obvious? If the advanced economies were booming, and consequently tax revenues were so high, and social insurance expenditures so low, that all the budgets were balanced and the long term fiscal outlooks were excellent, wouldn’t politicians everywhere be pushing for more tax cuts and more spending on their favorite programs?

If you are opposed to fiscal austerity, then you should be in favor of better monetary policy.

“I didn’t say that you and Morgan agree or don’t disagree just that he has made the same argument I am and yet you or no one else takes issue when he says it. He celebrates the idea that NGDPLT will keep the world safe for fiscal austerity-which is defintely his take on it as well. Did you read his quote? Yet when I point out the same thing it seems to perplex you.”

As a rule I almost never comment on anything Morgan writes, just as I almost never comment on anything Geoff (aka Major Freedom) writes. If I had to respond to every bat guano insane comment ever made in a econblog I wouldn’t have time to eat or sleep.

19. October 2013 at 15:28

Mark don’t get me wrong I’m not opposed to better monetary policy and neither is Krugman-he’s long since given his blessing to the Fed experimenting with NGDPLT or what have you. I have no problem with it either, and indeed would welcome it-I certainly welcotmed the Evan’s Rule. I just don’t see the need

to foreclose on fiscal policy.

The better way to go about it is to give us the optimal monetary policy that you and the MMers insist is possbile, certainly no Keynesians will stand in your way.

If you show results-we have very low unemployment and robust growth and most other important indicators look good then no one will be worrying about FS. However, we arent there and all we have your assurances that we will be if we follow you. It’s just the wrong progression of things.

As they say ‘show it don’t tell it.’ Telling me FS is never ncessary doesn’t persaude me nor does it if X amount of economists feel the same way. Let’s see the results that prove it-so far they haven’t been forthcoing-in this country certainly.

19. October 2013 at 16:20

I think, given the current political environment, that PK should stop talking about the ZLB and put all his weight behind monetary policy. Nothing is going to happen on fiscal policy anyway, so we might as well find out if the Sumnerites are correct.

20. October 2013 at 06:05

Luis and Philo, I agree.

Mike, The people standing in the way of easier money are the 6 (out of 7) people Obama appointed to the Board of Governors. So your claim that no Keynesians are opposed to easier money is flat out wrong. Lots of Keynesians are opposed. Polls also show this very clearly.

24. October 2013 at 08:54

It’s not that the policymakers should be indifferent to having 1% growth and 4% inflation vs 4% growth and 1% inflation: I am sure the policymakers should prefer the latter. The whole point is that targeting allows the first option, because a stable NGDP increases our chances of growth.

So the real question is if a policymakers should prefer 1% growth and 1% inflation or 2.5% growth and 2.5% inflation. The current regime seems to prefer the first option, and that’s not any good.

24. October 2013 at 17:38

Mark:

“As a rule I almost never comment on anything Morgan writes, just as I almost never comment on anything Geoff (aka Major Freedom) writes. If I had to respond to every bat guano insane comment ever made in a econblog I wouldn’t have time to eat or sleep”

Oh you’re just mad that you don’t have a rational response to my arguments.

18. February 2017 at 08:42

[…] http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=24239 […]