We trust central banks . . . to do the wrong thing

In recent months central banks have resorted to using the phony “credibility” issue. The claim is that they had to fight hard in the 1970s and early 1980s to get markets to believe they were serious about inflation.

Fortunately, that is simply not true. Markets have little difficulty figuring out what central banks are up to. When the central bank wants to reduce inflation (as they did after 1981) markets believe them. When they didn’t want to, markets didn’t believe they’d lower inflation. There never was a credibility problem.

In an earlier post I pointed out that this myth was partly due to a misreading of the early Volcker years. Volcker took over at the Fed in the fall of 1979, but it wasn’t until two years later that inflation started to fall significantly. But there shouldn’t be any big mystery as to why inflation didn’t fall earlier, money wasn’t tight earlier. For instance, in the spring of 1980 Volcker cut the fed funds rate from 17.6% to 9.0%, despite the fact that inflation in 1980 was over 13%, the highest in my entire lifetime.

Why would Volcker have done such a stupid thing? Why slash rates sharply (driving real rates far below zero) when inflation was running 13%? BECAUSE HE WASN’T FOCUSED ON INFLATION, HE WAS TARGETING REAL GDP. And we were sliding into recession in the first half of 1980, which threatened to cost Jimmy Carter his job. (Jimmy Carter appointed Volcker.)

Indeed that was the problem from 1967 to 1981. In late 1966 the Fed tightened slightly to slow inflation, which was gradually rising. The yield curve inverted. Normally we should have had a recession, but instead the Fed quickly switched to a policy of easing in 1967, and we merely had a slightly slowdown. Then we entered the 15 year period of very high inflation. If the Fed was trying to control inflation, they would have never once cut interest rates during that 15 year period, as inflation was always too high—usually much too high (although prices controls temporarily held it down in 1972). The Fed raised and lowered rates again and again during this period, because they weren’t trying to bring inflation down, they were targeting real GDP. Even worse, to the extent they cared about inflation at all, they were doing growth rate targeting, not level targeting.

After the Fed eased in 1980 by slashing rates, NGDP growth soared to 19.2% in 1980:4 and 1981:1. This scared Volcker so much that he finally put his foot down in mid-1981, and decided to do something about inflation. Inflation came down very quickly in late 1981, and ever since then the Fed has never had the slightest difficulty keeping inflation low. Nor has the ECB or the BOJ.

So the credibility problem is a complete myth. Where did it come from? It came from time inconsistency models developed in the early 1980s, which tried to explain why central banks created too much inflation. Unfortunately, no sooner were those models published than events discredited them, as central banks got inflation under control. Later Krugman tried the opposite tack–arguing too much credibility could lead to excessively low inflation in countries like Japan. Indeed that the BOJ might not be able to inflate if it had too much credibility. That model was also quickly discredited, as the BOJ tightened money twice (2000 and 2006) even as Japan was suffering deflation. It turns out both the conservative time inconsistency models and the liberal expectations trap models are completely wrong. Markets see very clearly what central banks are up to. If they are planning to inflate, the markets figure this out quickly. If they plan to let NGDP languish at excessively low levels, markets also figure that out, sometimes (as in late 2008) before the central bankers themselves even realize what they will do in the future.

And it’s not just financial markets. Wage contracts are more closely linked to NGDP growth than inflation, which is why wage growth stayed well behaved in 2008. As long as the Fed commits to a 5% NGDP trajectory, wage growth will remain quite stable, regardless of what happens to inflation.

This post was triggered by an excellent David Glasner post, which contains this gem:

Now, the ECB, having similarly focused on CPI inflation in Europe for the last two years, is in the process of causing inflation expectations to become unanchored in precisely the other direction. Why is it that central bankers, like the Bourbons, seem to learn nothing and forget nothing?

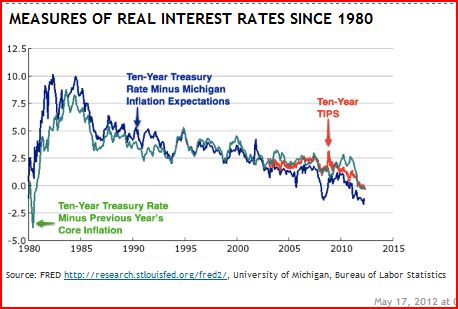

I’ve frequently argued that interest rate targeting is like a car with a steering wheel that locks when you need it most–on twisty mountain roads with no guardrail. I’ve also argued that although we rarely hit the zero rate bound in past recessions, it may well become the norm in future recessions. This graph provided by Brad DeLong shows why:

Focus on the red line. Real yields on 10 year TIPS seem likely to fluctuate between 0% and 2% in the future, with the lower rates occurring in recessions. If we target inflation at 2%, then nominal yields on 10 year Treasuries will fall to about 2% in future recessions, which means short rates will hit the zero bound. It’s not just this recession; we’ve seen a secular decline in risk-free real rates going back for decades.

The Fed is committed to a policy that failed in this cycle, and will keep failing until they figure out what they are doing wrong. Fortunately (as is obvious from my previous two posts), the profession is catching on quickly, so let’s hope this is the last time we see central banks so inept during a major crisis.

PS. Yes, it’s true that inflation fell a bit faster than markets expected during the 1980s. But it’s equally true that inflation fell faster than Volcker wanted in the 1980s.

Tags:

18. May 2012 at 05:55

Interest post.

In the UK short term (3.5 year) implied inflation expectations are 2.18% RPI, (roughly 1.43% CPI vs 2% CPI target).

However, long term inflation expectations (25 year) are 4.15% RPI, (or ~3.4% CPI).

Is the gilt market expecting a change in inflation target in the medium term?

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/Pages/yieldcurve/default.aspx

18. May 2012 at 06:17

Altig at the Atlanta Fed actually felt compelled to respond to Frankel’s RIP Inflation targeting commentary (with more defense of credibility and the greatness of the Fed’s new 2% ceiling strict inflation target that Lacker loves so much).

some days i feel like its tilting at windmills, but the good news about Altig’s post is that people inside the Fed clearly are feeling the Tsunami.

18. May 2012 at 07:12

asdasdasd, Interesting. My admittedly ad hoc theory is that the tail risk is all on the upside. People in Britain don’t worry much about deflation, but high inflation is a possibility if the debt situation keeps getting worse. If I’m right the most likely inflation rate is lower than the expected value (essentially the median/mean distinction that often crops up.)

So 2% inflation might be more likely than 3.5% long term, but 10% might be far more likely than negative 6%.

dwd, They also defended the gold standard to the bitter end. And then there’s the euro . . .

18. May 2012 at 07:28

They also defended the gold standard to the bitter end. And then there’s the euro . . .

You are talking to someone who comes from a long line of hard headed, stubborn, over educated people. i tell my kids all the time its better to learn from other peoples mistakes than their own, but they would very often rather make their own. sigh.

the even better news, WSJ linked to Altig’s rebuttal, and Altig also allowed my somewhat rant-ish Fed bashing rebuttal of his rebuttal.

my view is that the more eyeballs the better, the argument sells itself.

18. May 2012 at 07:31

But Tyler says we are on our way out of TGS…

18. May 2012 at 08:45

Interesting post. When-and how much-did Volcker “go Monetarist” and try to control the growth of the money supply?

18. May 2012 at 09:01

dwb: I read both articles and I must say that there is something that troubles me with this NGDP tsunami. Maybe it is just an omission, but many people seem to ignore the word “level” in NGDPL targeting. And I would say that I would consider it be better to have price level targeting then year-on-year NGDP targeting of internal forecast/market futures of NGDP groth.

This only gave Altig an excuse to bash NGDP targeting by giving word to fears that NGDP will be to volatile. And as another hypothetical question to Altig – if he so worried about “stable prices” – that he clearly considers as not volatile year-on-year headline inflation, then how does he explain 2008 crisis deflation? It certainly seems that IT did not do a good job in a metrics that he advocates.

18. May 2012 at 09:17

If they plan to let NGDP languish at excessively low levels, markets also figure that out, sometimes (as in late 2008) before the central bankers themselves even realize what they will do in the future.

If the market figured out what the Fed was going to do starting late 2008, there is no reason to call for more inflation now. Expectations are already built in to the status quo. It would be like saying 5% NGDP with 5% expectation is “better” than 4% NGDP with 4% expectation. Yet you’ve said on multiple occasions any NGDP is fine as long as expectations match up with it.

Wage contracts are more closely linked to NGDP growth than inflation, which is why wage growth stayed well behaved in 2008. As long as the Fed commits to a 5% NGDP trajectory, wage growth will remain quite stable, regardless of what happens to inflation.

Nominal wages may go up with inflation of money, but real wages stagnate the more inflation there is. Real wages since the early 1970s have stagnated:

http://i.imgur.com/InBUV.gif

http://i.imgur.com/pCZWg.png

Hmmm, I wonder what major monetary event happened in the early 1970s? Oh, I know! It’s when the last vestiges of the silly gold standard which only benefited rich people, was finally abandoned, so that poor people can believe from then on that they are first in line to the printing press and can buy wealth from evil stingy capitalists who would otherwise only cater to other wealthy people!

Monetarism is not totally asinine. It makes perfect sense. We need real wages to come down even more via inflation. Most poor people can still eat after all.

18. May 2012 at 09:30

I wonder if 3.4% CPI corresponds to a 5% NGDP target in Britain, given the supply-side problems there?

asdasdasd wrote:

“or ~3.4% CPI”

ssumner wrote:

“My admittedly ad hoc theory is that the tail risk is all on the upside. People in Britain don’t worry much about deflation, but high inflation is a possibility if the debt situation keeps getting worse.”

18. May 2012 at 09:38

I’ve frequently argued that interest rate targeting is like a car with a steering wheel that locks when you need it most-on twisty mountain roads with no guardrail.

I’ve frequently argued that aggregate spending targeting is like spiking the punch bowl with more alcohol whenever people drink less of it in volume, so that the binge party doesn’t stop. When people are getting so sick that they try to drink less, “naively” thinking that it will cure their sickness, it’s all for naught, because the less they drink, the more potent the punch becomes.

After all, the host of the party knows better. They know that the party goers don’t “really” don’t want to stop partying. If every individual party goer drinks less, that would otherwise cause party deflation, which would end the party, and decrease all the vital statistics such as laughter, movement, dancing, and other signals of “economic activity.”

When the party goers drink less because they’re getting sick, it doesn’t mean they want to drink less alcohol. What it “really” is, is just their desperate, helpless plea to the host to make the punch more potent. I mean, it’s OK if one party goer reduces his drinking, but only as long as someone else drinks more. If everyone reduced their drinking, then that’s a whole different cocktail. For now, with many individuals reducing their drinking, the party poopers run the risk of ending the party for themselves, and they don’t want to stop partying. Nobody stops drinking because they want the party to end. They just don’t realize that sometimes, what’s good for them as individuals just isn’t good for “the party.”

The party must go on. Why? I don’t know, but I know it must. Don’t ask me why. The alcohol is here, so deal with it. Given that the punch is being spiked, it is optimal if the punch increases in volume by 5% per hour. That way, if people drink more, less alcohol will go in, and if people drink less, more alcohol will go on. We need to keep the people in a nice, smooth, stable buzz. Too much alcohol and they wreck the place. Too little alcohol and they stop the party and go home, leaving the host and his friends without a job, and the host has the guns, so he’s in charge.

Never mind the fact that people’s alcohol tolerance will go up over time, thus necessitating an increasing rate of alcohol going into the punchbowl to keep the binge party going. It’s all about the buzz.

18. May 2012 at 09:46

@ J.V. Dubois

I read both articles and I must say that there is something that troubles me with this NGDP tsunami. Maybe it is just an omission, but many people seem to ignore the word “level” in NGDPL targeting.

I am not sure which two articles you mean. I often omit “path” myself (because its very clear to me what I mean, yes “path level targeting” is better IMO).

I strongly encourage you to submit comments to Altig’s blogs, he actually does read them as part of moderation (he has sent me emails). But yeah i think that Altig’s response speaks for itself: the job of every central banker these days is to see inflation always and everywhere and we never screw up!

18. May 2012 at 11:37

Scott and all participants of this forum:

This is somewhat off the subject, but very important at this time. What is your assessment of the two persons who have FINALLY filled the vacancies on the BOG. Are they more likely to take the Fed’s mandate to achieve maximum employment seriously than the current make up of the FOMC? Will they push monetary policy to a more expansionary path or not, or even toward a less expansionary path?

One defense that has been proffered for Bernanke not doing more is that he would like to do more, but does not have the votes. If that is really the case, will this give him the votes?

Will market anticipations of what they will do have a significant immediate effect on the financial markets?

And how were these appointments gotten past the Republican obstructionism?

18. May 2012 at 11:53

dwb, That’s good to hear.

Saturos, Are you sure he wasn’t joking?

Mike Sax, Money growth was highly unstable under the 1979-82 “monetarist experiment.”

JV, Yes, level targeting is key.

Steve, Yes, but the most likely NGDP growth rate is more like 4%, as the most likely inflation rate is lower than the expected value of inflation.

FEH, We know little about their views, which is precisely the problem. Only world class monetary policy researchers should be put on the Board. We need 12 Bernanke types.

Obama really blew it with these appointments–he didn’t realize how important they were. 6 of the 7 Board members are now Obama people!

18. May 2012 at 12:28

Scott if Vitter and Corker are right about their views then they’re great.

“”Sen. Bob Corker (R., Tenn.) said that while the nominees might not be as focused on price stability as he would prefer, he deemed them qualified for the board. The Fed has a dual mandate that charges it with pursuing both steady prices and maximum employment. Critics of the Fed have worried that its policy of super-low interest rates could spur inflation.”

“These two nominees candidly do not represent the kind of more hawkish position that I would like to see the Federal Reserve take where they’re concerned about price stability over the long haul,” Mr. Corker said on the Senate floor Thursday.

http://diaryofarepublicanhater.blogspot.com/2012/05/obamas-fed-nominees-finally-confirmed.html

Let’s just hope Corker’s characterization is accurate. If so then Obama made some good picks.

18. May 2012 at 13:57

“If so then Obama made some good picks.”

Obama was severely constrained by having to get his nominees past the Republican filibuster and this may be the best he can do. If that political constraint did not exist, these are obviously not the optimal choices. Optimal choices would be people that understand that the Fed can and should increase the growth in AD, or, in a dynamic setting NGDP growth, in order to make the economy grow fast enough to get the unemployment rate down. For example, Christina Romer. Also, for the sake of bipartisanship, a Market Monetarist who does not want to use monetary policy to cause Obama to lose the election.

18. May 2012 at 14:00

“We need 12 Bernanke types.”

Not so. We need 12 who understand that with inflation low and unemployment unacceptably high, the dual mandate calls on the Fed to engage in a more expansionary monetary policy than Bernanke favors.

18. May 2012 at 17:56

Scott,

Just so you’re aware, I believe you picked up the ‘steering wheel that locks up on top of the mountain” metaphor from Matt Yglesias. I remember you praising his vivid imagery.

19. May 2012 at 08:30

Mike, Let’s hope so.

FEH, But he didn’t make good choices when the Dems had 60 votes in the Senate, so I doubt that’s the constraint.

By Bernanke types I mean people who understand monetary policy. If there were 12 Bernankes right now on the Fed, they’d be much more expansionary in my view.

Ben, It might have been sarcasm, as he often gets his monetary posts from us market monetarists. Sometimes I quote him and praise him for a brilliant idea, when he borrows something I did a few days earlier.

BTW, That happened to me while driving a Ford Pinto on a twisty mountain road in 1976, so I know what it feels like.

19. May 2012 at 14:56

“But he didn’t make good choices when the Dems had 60 votes in the Senate,”

AGREED!

During the beginning of the Obama administration, when he made no attempt to fill two vacancies for over a year, I was completely puzzled by this omission. Were the Republicans obstructing? Or what? I tried Googling this and found virtually no discussion. (Unfortunately I had not found this site yet.) And I could not understand why, once the Republicans were obstructing, Obama did not try to make recess appointments of people who prioritized full employment. Obama’s economic advisors really let him down on this.

If Obama loses, the failure to promptly fill the posts with people who recognized the need and ablility to use monetary policy to get the unemployment rated down at a solid rate, and the reappointment of Bernanke may well be the errors that did him in.

If Obama wins and has the votes in the Senate to do it, he should replace Bernanke with Christina Romer.

20. May 2012 at 15:01

FEH:

Not so. We need 12 who understand that with inflation low and unemployment unacceptably high, the dual mandate calls on the Fed to engage in a more expansionary monetary policy than Bernanke favors.

Inflation isn’t low.. It’s 2.5%, from a local high of almost 4% in late 2011.

And didn’t the experience of the 1970s refute the “inflation = jobs” doctrine?