In a recent post I discussed 4 possible interpretations of Tyler Cowen’s post on risk-based recessions:

Perhaps the claim is that we might have a recession this year due to risk, despite 3% plus NGDP growth. If so, I very strongly disagree. (This could be viewed as a version of real business cycle theory.)

Perhaps the claim is that if there is a recession, then NGDP growth will slow, but that this will not be the cause. In other words, even in a counterfactual world where the Fed kept NGDP growing at 3% plus, there would still be a recession for non-monetary reasons. If so, I very strongly disagree. (Again, an RBC-type claim.)

Perhaps the claim is that falling NGDP growth is a necessary condition for a recession this year, but it will be caused by growing risk and there is nothing that monetary policymakers can do about it. If so, I strongly disagree. (A traditional Keynesian claim)

Perhaps the claim is that falling NGDP growth is a necessary condition for a recession this year, but it will be caused by growing risk that monetary policymakers are too cautious to do anything about. If so, I mildly disagree. (A New Keynesian claim.)

Tyler has a new post that discusses some of these issues. He does not refer to this list, but as far as I can tell he has a fairly eclectic view of business cycles, and thus probably doesn’t want to get pinned down to any single hypothesis. I’ll go further and speculate that he believes both the RBC and the Keynesian explanations may each apply in some cases. That is, sometimes recessions are caused by real shocks, and could not be prevented even if the Fed were able to stabilize NGDP growth. And sometimes there are shocks that it is more useful to think of as “non-monetary” even though they work at least partly through the channel of causing NGDP changes that destabilize the economy. Perhaps because of some problem such as policy lags or the zero bound, the central bank may not be able to prevent those NGDP shocks, and if they are ultimately caused by some other factor, such as financial distress, then it makes more sense to see the recession as being caused by the financial distress, not the “tight money” label that MMs pin on falling NGDP.

I’m not certain I’ve interpreted his views exactly right, but I’ve tried to state them in a way that I think is quite defensible.

The post also has an extensive critique of areas where market monetarism may overreach, i.e. make claims that are unsupported by evidence, if not borderline tautological. As I read though this criticism I kept coming back to an observation that seems central to me, but perhaps not to Tyler. I see his strongest criticism as boiling down to something like “Market monetarism is flawed because we lack a real time indicator of NGDP expectations.” (My words not his.) That is we lack a NGDP futures market. And that is indeed a big flaw.

Right now lots of smart market analysts, like Jan Hatzius, suggest that financial conditions have recently tightened enough to slow growth by 1% to 1.5%. But it would be better if we had a NGDP futures market. Indeed even last year at this time we had the Hypermind prediction market, which although flawed, was good enough to give ballpark NGDP estimates. It showed that no recession was expected in 2015. But now we lack even that.

This is important because MM theory says NGDP expectations are the proper measure of the stance of monetary policy. Lacking that market, we sometimes fall back on actual NGDP. And Tyler points out that if the central bank targets inflation, then NGDP and RGDP shocks would be perfectly correlated, even if there were no causal link.

So far I’ve been trying to describe his argument in as positive a way as possible. Now I will start disagreeing:

Here is a recent Scott Sumner post, mostly about me. It’s basically taking the other side of what I have been arguing, and I would suggest simply disaggregating the ngdp terminology into a more causal language of nominal and real shocks. Surely there are other independent, ex ante signs for judging the tightness of monetary policy, rather than waiting for ngdp figures to come in, which again is citing a transform of the real gdp growth rate as a way of explaining real gdp.

I find these issues come up many, many times in market monetarist writings. I think they have basically the right policy prescription, and could provide the world with billions or maybe even trillions of dollars of value, if only policymakers would listen. But I also think they are foisting a language of causality on the business cycle problem which the rest of economic discourse does not easily absorb, and which smushes together real and nominal shocks into a lower-information accounting variable, namely ngdp, and then elevating that variable into a not entirely deserved causal role. We ought to talk in terms of ex ante, independent measures of monetary policy looseness, not ex post measures which closely resemble indirect transforms of real gdp itself.

My focus when estimating the stance of monetary policy has generally been NGDP forecasts, not actual NGDP. And NGDP forecasts are available in real time, and hence not subject to the “waiting for ngdp figures to come in” critique above. This point can be made much more effectively by focusing on the past two months. Tyler says money is not that tight:

I say [monetary policy is] “not that tight,” while leaving room open for the possibility that it should be looser.

What metrics might we look at? Federal funds futures no longer expect imminent further rate hikes from the Fed. Expected rates of price inflation have been very close to two percent. No matter what you think about the structural component of labor supply, cyclical unemployment has recovered a great deal over the last few years. And that is through the period of “taper talk” of almost two years ago. Consumer spending is doing OK, not spectacular but not cut off at the knees. And while in very recent times price expectations are headed downwards away from two percent, this seems to stem from negative real shocks, to which the Fed has responded passively (perhaps unwisely). That’s different than the Fed tightening. There was a quarter point rate hike from December, which is a small tightening for sure, but I don’t see much more than that.

Here’s where I strongly dissent from the thrust of Tyler’s argument.

1. The fact that markets now expect zero Fed funds rate increases this year, not the two expected (or 4 promised) in December, is not a sign that money is getting looser, it’s more likely a sign it’s getting tighter. While on any given day a rate increase is tighter than not increasing rates, over a 12-month period policy is highly endogenous. If a crystal ball told me rates would be at zero for another 20 years, I’d take that as evidence that money is currently way too tight.

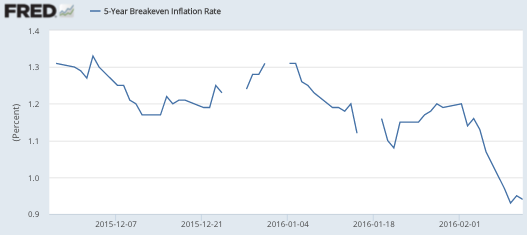

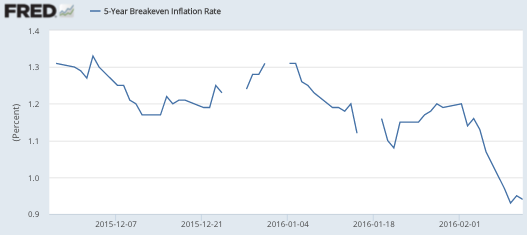

2. Tyler’s claim that expected inflation is 2% is linked to an earlier post, which discusses not market forecasts, but the forecasts of economists. Two months ago the consensus of economists called for about 1.8% to 1.9% PCE inflation over the next few years. But even then, 5 year TIPS spreads showed about 1.2% to 1.3% CPI inflation, which is about 1.0% PCE inflation. And as the following graph shows, market inflation forecasts have fallen much further in the past two months, so even if policy was roughly on target in December 2015, it’s too tight now.

3. A quarter point rate increase in December may or may not be a “small tightening”. The size of the rate increase is not a reliable gauge of the degree of tightening, because monetary policy affects rates in two partially offsetting ways (the liquidity effect vs. the income/Fisher effects). Important recessions (US 1937, Japan 2001, eurozone 2011) have been caused by very small rate increases.

4. The recovery in the labor market doesn’t tell us much about the risk of recession, other than that we aren’t in one yet.

5. Any “real shock” that reduces NGDP expectations because the Fed responded passively is also a monetary shock. It could be both monetary and real. If frightened Venezuelans started hoarding US currency and the Fed didn’t print any more currency, and NGDP fell, I’d call that a tight money policy even if it was “passive.” In any case “passive” is a meaningless concept in monetary policy, as change can occur along many dimensions; fed funds target, reserve requirement, the monetary base, IOR, exchange rates, price of gold, TIPS spreads, etc., etc. At any give moment, policy will be active along some dimensions and passive along others.

My views on current business conditions are pretty similar to those of Tyler, AFAIK. I think we both see a modest risk of recession this year, but less than 50-50. So suppose there is a recession this year—can I say, “I told you so”? I certainly didn’t think the rate increase in December would lead to recession (although some other MMs were more pessimistic.) But that misses the point. Sorry to be so long winded, but wake up here, this is the key point.

The Fed needs to always keep the “shadow NGDP futures price” close to target. If at any time they let it slip, as they did in September 2008, and if MMs point out that it is slipping, and if the Fed does not take aggressive actions that it clearly could take to prevent if from slipping, then yes, it’s the Fed’s fault.

That italicized statement does not involve any Monday morning quarterbacking. I’m not going to blame them for anything that they cannot prevent in real time. But recall that currently they are not even at the zero bound. Let’s explain this with a simpler example. We do have TIPS spreads, so we don’t need shadow prices for inflation expectations. MMs claim that even with the liquidity bias in TIPS spreads, the current ultra-low 5-year spread suggests money is too tight for the Fed’s 2% inflation target. That doesn’t mean we’ll have a recession, but if the Fed wants to hit their 2% inflation target they need to ease policy. If they don’t, and if they fall short of their inflation target, then MMs will have been right.

Now I think it’s possible that the Fed will luck out here, and perhaps even hit their inflation target. But on balance I believe markets are right more often than not, and the Fed will once again fall short.

Note that if we had a good NGDP futures market I could have reduced the length of this post by 80%. It would be easy to address Tyler’s various points by referring to NGDP futures prices. Either they predict recession or they don’t. Either they are controllable at the zero bound or they are not. They would be real time indicators, with no Monday morning quarterbacking involved. But we don’t have that market, so the best we can do is estimate a shadow price of NGDP futures by looking at TIPS spreads, bond yields, stock indices, commodity prices, and a zillion other factors, and construct the best estimate we can of the current market NGDP forecast. That’s the key variable for me, not actual NGDP.

Actual NGDP comes in to play when we consider level targeting. MMs believe not just that level targeting would make recessions shorter, we also think it would make them less likely in the first place. So the one area where we are justified in criticizing the Fed based on actual NGDP numbers is the level targeting issue; are they trying to get us back to the trend line? If they don’t level target, then recessions are more likely to occur, and will be deeper.

PS. I’m not sure what Tyler means by saying NGDP is a transform of RGDP. Does this mean NGDP * (1/p) = RGDP? If so, isn’t that true of any variable?

M * (V/P) = RGDP

In general,

X * (RGDP/X) = RGDP, where X is the price of a can of tomato paste.

Nor do I understand the “tautology” remark attributed to Angus. Obviously it’s not a tautology for Zimbabwe. The only way I can make sense of this complaint is that the Fed actually does target inflation, so it makes sense to assume P is stable, whereas it doesn’t make sense to assume V/P or (RGDP/X) is stable. And if we assume P is stable then NGDP and RGDP become highly correlated. Fair enough. But as Nick Rowe recently point out, what matters is the counterfactual where NGDP is kept stable. Which brings us back to the list at the top of this post. I think MM critics need to think long and hard about exactly which of those four critiques is the most important, and what sort of empirical evidence we’d use to evaluate that critique.

PPS. I also have a new post over at Econlog.

PPPS. I will be doing a “Reddit” on the 23rd at 1 pm, whatever the heck that is. “Ask me anything.”