Progressives of the younger generation may wonder what led to the curious phenomenon of “neoliberalism.” Why did some 1960s progressives gradually become more conservative over time? There are many reasons, but crime is one issue that almost certainly played a role. Take a look at the US murder rate from 1950 to 1962 (per 100,000):

1950 – 4.6

1951 – 4.4

1952 – 4.6

1953 – 4.5

1954 – 4.2

1955 – 4.1

1956 – 4.1

1957 – 4.0

1958 – 4.8

1959 – 4.9

1960 – 5.1

1961 – 4.8

1962 – 4.6

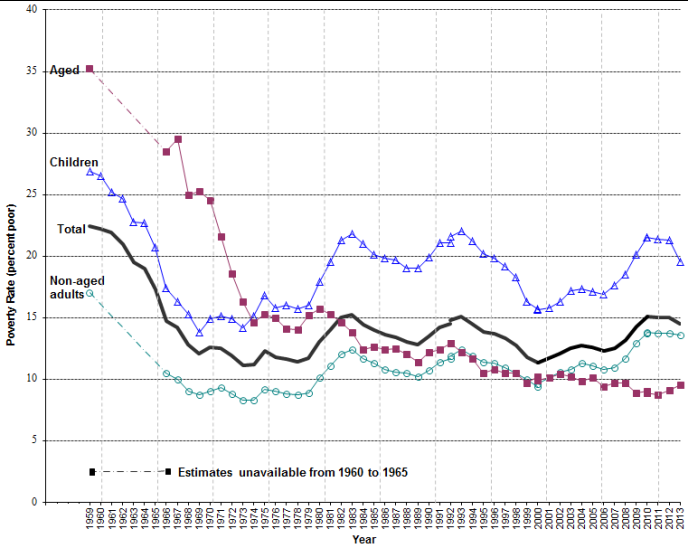

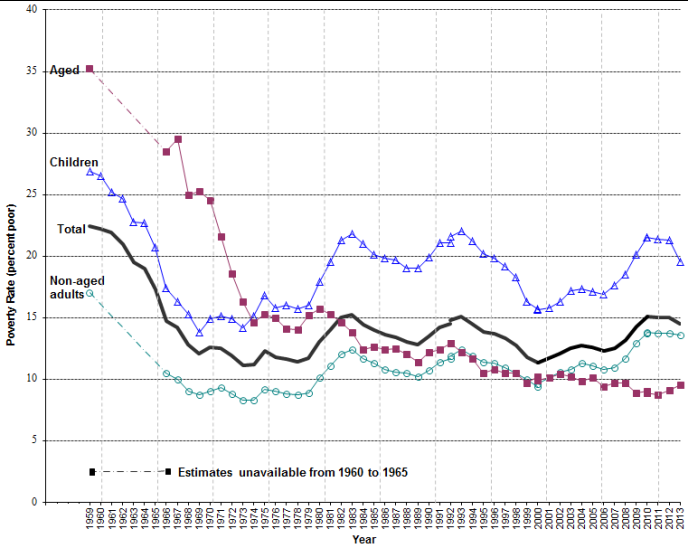

No net change, but pretty high. Suppose that like all good liberals you believe that America’s unusually high murder rate is due to poverty and guns. What would you expect to happen to that murder rate if the US succeeded in dramatically reducing the poverty rate over the next 12 years? You’d obviously expect a sharp fall in the murder rate. First, here’s what actually happened to poverty:

Take a look at the poverty rate in 1962, about 21%. That’s down slightly from previous decades, but still pretty high. Then something dramatic happened, poverty started falling really fast. In 1964 LBJ announced a “War on Poverty,” although to be honest the decline began even before those programs really kicked in a few years later. I’d guess the civil rights movement also played a role, as did the economic boom of the 1960s. By 1974 the poverty rate was less than 12%.

Take a look at the poverty rate in 1962, about 21%. That’s down slightly from previous decades, but still pretty high. Then something dramatic happened, poverty started falling really fast. In 1964 LBJ announced a “War on Poverty,” although to be honest the decline began even before those programs really kicked in a few years later. I’d guess the civil rights movement also played a role, as did the economic boom of the 1960s. By 1974 the poverty rate was less than 12%.

And here’s what happened to the murder rate during the golden boom years of plentiful jobs for the working class and amazing poverty reduction:

1963 – 4.6

1964 – 4.9

1965 – 5.1

1966 – 5.6

1967 – 6.2

1968 – 6.9

1969 – 7.3

1970 – 7.9

1971 – 8.6

1972 – 9.0

1973 – 9.4

1974 – 9.8

OK, 1974 wasn’t so “golden,” but you get my point. The murder rate stayed high until 1991 and then started falling. In 2012 it’s back down to 4.7, having fallen from 5.9 to 5.0 just during the Great Recession of 2007-09 (as poverty soared). And the big crime surge of 1963-74 was not due to riots, which petered out after 1970.

The huge crime wave of the 1960s and 1970s was one of the things that finished off old liberalism. Old liberalism is now being revived by a generation of progressives too young to remember why their parents or grandparents became disillusioned.

BTW, other forms of crime such as rape, robbery, burglary, and assault increased even more rapidly during the 1960s and 1970s. However the murder rate data is regarded as more reliable. I was very young back then, but I do recall that people were pretty shocked by the surge in crime. Nixon was elected president on that issue. All the liberal east coast states except Massachusetts voted for Nixon in 1972. Imagine someone running today (for federal office) on the crime issue. Weird.

I don’t have any answers here; just that poverty reduction is not a cure for crime. Poor people are more likely to commit violent crimes, but we don’t really know why.

The New York Review of Books has an interesting piece on the War on Poverty. I chuckled when they said that neither liberals nor conservatives could make up their minds as to whether poverty has declined sharply (the war worked!) or whether poverty has declined sharply (the war is no longer needed!) As soon as the liberals and conservatives figure out what a decline means, they’ll all line up predictably on each side the debate over empirical studies. The article also contains this gem, as if we needed any more reasons to ignore all income inequality data:

Cohabiting couples. Imagine two twenty-five-year-olds who are romantically involved, live together, and each earned $12,000 in 2013. If they were unmarried, the Census Bureau would have classified them as unrelated individuals, with poverty thresholds of $12,119 each. Since their incomes were only $12,000, the bureau would have counted them both as poor. They would each have needed at least $12,199, bringing their total household income to at least $24,238, for the bureau to stop counting either of them as poor.

Had they been married, however, the bureau would have taken a more upbeat view of their economic situation, classifying them as a family of two with a poverty threshold of $15,600. As a result of this change they would both have been above their poverty threshold instead of below it. According to the Census Bureau’s most recent data, 11 percent of all opposite-sex couples who lived together in 2012 were unmarried.2 We don’t have such a figure for 1964, but it was probably only 1 or 2 percent. The assumption that cohabiting couples need more income than married couples has therefore raised the official poverty rate. This increase in the poverty rate would make sense only if the absence of a marriage license increased a couple’s expenses by 55 percent (from $15,600 to $24,238). The Census Bureau has never tried to defend that assumption, presumably because it is a byproduct of rules set by the Office of Management and Budget, which the Census must follow whether it likes them or not.