Money and Inflation, Pt. 1 (The long twilight of gold)

In a previous post I argued that money is important because it pins down nominal variables like the price level and NGDP. In this post and the next couple, I’ll explain how money determines the price level. Let’s start with the most common monetary system in modern world history—the silver standard. Indeed let’s assume that the unit of account is one pound of sterling silver, or “pound sterling” for short. Silver itself is the medium of account.

Money can be defined in many ways, including the medium of account, the medium of exchange, or highly liquid assets. I believe the medium of account definition is the most useful, as it will allow us to quickly zero in on the key issues, without the distractions of media of exchange that might or might not be convertible into silver.

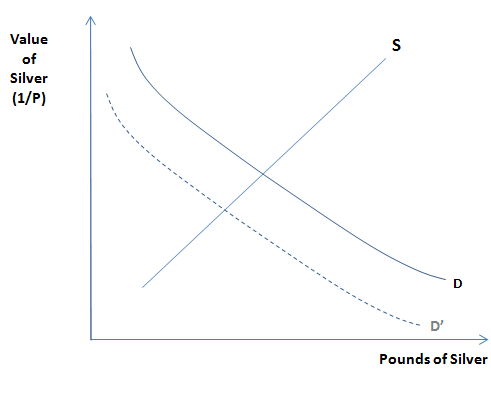

As noted earlier, the value of the medium of account (let’s call it “money”) is equal to 1/P. The price level is determined in the silver market. Modeling the (long run) price level is a microeconomic problem. However the various effects of changes in the price level are macroeconomic problems. Here’s how simple it is to model the (long run) price level when silver is money:

When there is a new silver discovery that shifts the supply of silver to the right, the value of silver falls and the price level rises inversely proportionately to the fall in the value of money—by definition. There is no quantity theory of money yet; that will come later with fiat money (although ironically the theory was invented during a commodity money period where it doesn’t quite apply.)

Eventually most nations switched onto a gold standard regime; in the US the unit of account was the dollar, defined as 1/20.67 ounces of gold (until 1933.) Because governments generally don’t operate gold mines, monetary policy consists of one tool, and one tool only, shifts in the demand for gold. This can be done in all sorts of ways, such as changing the amount of gold backing each paper dollar via OMOs or discount loans, or by changing reserve requirements so that banks demand more currency, which leads to a greater derived demand for gold to back that currency. Less demand for gold was expansionary (shown on graph), and vice versa. Small countries obviously had little impact on the value of gold, which was determined in global markets.

Under a gold standard there was a “zero lower bound problem” for gold reserves, which Keynes misdiagnosed as a liquidity trap. Thus it’s easier to do tight money than easy money, because easy money is constrained by the fact that central bank gold demand (gold reserves) cannot fall below zero.

Most people think this is why the US left the gold standard in 1933. However we didn’t really leave the gold standard, we just temporarily suspended it, and we were never even close to running out of gold reserves. It’s not clear what the real problem was—perhaps FDR couldn’t get the Fed to inflate as much as he wished, and thus did an end run by raising the price of gold. Even so, the dollar was re-fixed to gold in 1934, and stayed fixed until 1968, when we finally stopped using gold as a medium of account.

The long phase-out of gold lasted for 34 years, and saw a very large rise in the price level. This inflation can be attributed to three factors, two of which reflected decisions of FDR, and the third was luck:

1. The revaluation of gold from $20.67 per ounce to $35/oz. This alone raised prices by 69%.

2. FDR reduced global gold demand by making it illegal for Americans to hoard gold. Later American presidents reduced the gold/currency ratio.

3. Most of the remaining gold demand was in Europe. The Depression, rearmament, and WWII put enormous pressure on their economies, leading to a dramatic reduction in European gold demand.

Even so, by the mid-1960s US policy was so expansionary that there were expectations that we’d eventually leave the gold standard. Finally in 1968 we closed the gold window to foreigners (other than governments) and the free market price rose above $35. The gold standard was finished, never to return.

Why the 34 year phase-out? People today cannot imagine how entrenched gold standard thinking was back in 1933. Contrary to widespread belief even Keynes was vehemently opposed to a pure fiat money regime—instead favoring an adjustable peg to gold. The post-WWI hyperinflations were fresh in peoples’ minds, and if you talked about the virtues of fiat money in 1933, any “Very Serious Person” would have simply pointed to Weimar Germany. End of discussion.

By 1968 the post-war Keynesian model was dominant, and money had been pushed into the background—not to reappear until the Great Inflation reminded people of its importance.

Next we’ll develop a model of fiat money. It will also feature a price level determined by the supply and demand for the medium of account (which is now cash), but there are several important wrinkles that lead to dramatically different policy implications.

PS. You might wonder why all the inflation didn’t occur between 1933 and 1945, instead of continuing during 1945-68. After all, the three factors I discussed above all occurred in the earlier period. The answer is that the Fed hoarded vast quantities of gold during 1933-45, which held down inflation. Then they gradually reduced their demand for gold after WWII, and hence prices kept rising during the 1945-68 period.

PPS. Doesn’t silver now cost about 300 pounds per pound? That’s some serious currency debasement.

PPPS. I hope Brad DeLong is right, as I’ve spent most of my adult life studying the Great Depression:

Second, you never know what parts of history may turn out to be useful and very important. Ten years ago I thought that my curiosity about and interest in the Great Depression was an antiquarian diversion from my day job of understanding the interaction of economic institutions, economic policies, and economic outcomes. The fact that we had gone through the Great Depression, had learned lessons from it, and had incorporated those lessons into our institutions and policy processes meant that there was little practical use to going over it once again. Boy, was I wrong. History may not repeat itself, but it certainly does rhyme””and nothing made an economist better-prepared and better-positioned to understand what happened to the world economy between 2007 and 2013 than a deep and comprehensive knowledge of the history of the Great Depression.